Introduction

Volunteer organizations help communities in a variety of ways, and volunteers serve in various capacities relating to projects, goals, and tasks. In fact, the current estimated value of a volunteer is $28.54 per hour (Independent Sector, 2021). With these varying roles, there are possible risks that volunteers, clients, and the organization can encounter. Risk management is a tool that many volunteer organizations and volunteer leaders should consider when thinking of the safety and protection of their organization and its volunteers. It is the role of the organization’s volunteer leader to coordinate an effort and manage such risks for the volunteer organization. An organization’s volunteer leader is someone who recruits and manages volunteers for their organization.

What is risk?

When considering volunteerism as an option for an organization, it is helpful to remember there is risk in any volunteering capacity, whether online or face-to-face. Risk is defined as “a potential loss or harm” (Connors, 2012, p. 323) and can be categorized in five different ways: (a) people, (b) property, (c) income, (d) goodwill, and (e) liability. All volunteer activities incur a risk, and volunteer leaders and organizations should attempt to minimize and manage such risks (Cravens & Ellis, 2014), because there is never any sure way to eliminate a risk other than removing all volunteer action from the organization (Connors, 2012). Volunteer leaders and managers often describe risk as negative or bad; however, risk can also be positive. Herman and Chopko stated, “an organization that designs its risk management activities solely around the goal of minimizing or avoiding risk will miss out on opportunities to strengthen the organization’s assets” (2009, p. 3). Organizations must take both positive and negative risks to carry out their mission.

The Risk Management Model

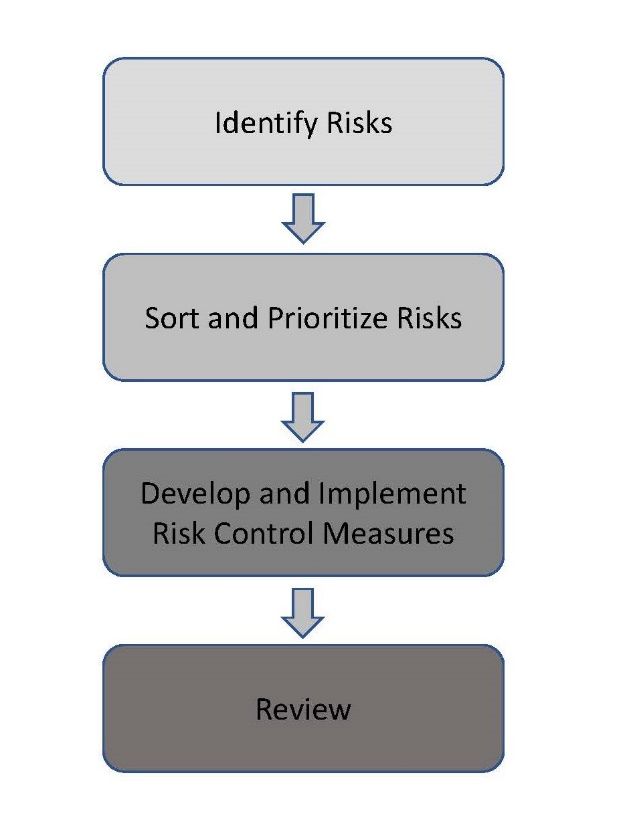

Volunteer leaders can utilize the Risk Management (RM) Model to help them assess any current or potential risk within their organization. The RM Model (see Figure 1) is a four-step planning process that leads an organization’s team through a “series of steps, allowing and encouraging consideration of a range of action and decision alternatives” (Connors, 2012, p. 337). This model is important because it provides the framework within which a feasible risk management plan can be developed for volunteer service.

Credit: Connors, 2012

Step 1: Identify Risks

A volunteer organization will first start with identifying what risks already exist and predicting potential risks. Taking a single task or project one by one through brainstorming, foresight, and fantasy can decrease the likelihood of missing risks that could materialize into actual loss, harm, or opportunity (Connors, 2012). During this step, it is recommended that the organization’s stakeholders and volunteers who are familiar with the different responsibilities of the organization provide feedback, because they will notice different aspects of the risks that were not considered before. When organizations are identifying these risks, all risks are considered, even the risks that are under control (Connors, 2012). Potential risk areas for volunteer organizations to consider include:

- Previous harm or loss

- Potential losses

- Fundraising events

- Volunteer-delivered client services

- Other volunteer-based programming

- Volunteer program management issues

- Material resources

Step 2: Sort and Prioritize Risks

The first step, risk identification, tends to unveil more risks than the volunteer organization can react to. The volunteer leader must then begin to sort and prioritize which risks are more important to focus their time and attention on, which is step 2 of the risk management process. The objective of this step is to “identify the most urgent risks that demand immediate attention, and further prioritize the remaining list by degrees of urgency” (Connors, 2012, p. 344).

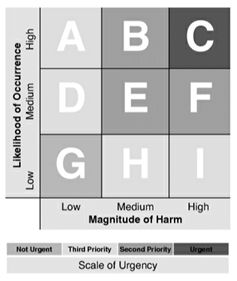

Volunteer leaders need to assess the likelihood of occurrence and the magnitude of harm of the risks to the organization. Likelihood of occurrence is described as the risk that is or could materialize into actual loss or harm, whereas magnitude of harm is described as how significant a risk consequence could be to the organization (Connors, 2012). Volunteer leaders can use the Risk Priority Map to help them visualize and assess the degree to which the risk could harm the organization (see Figure 2). The following scale can be used to determine which risks should be prioritized highest:

- Urgent (1st priority risks)—Cell C

- As soon as possible (2nd priority risks)—Cells F, B, and E

- Work through when time permits (3rd priority risks)—Cells A, I, D, and H

- Not urgent (4th priority risks)—Cell G

Credit: Connors, 2012

Step 3: Develop and Implement Risk Control Measures for Volunteers

A layered strategy for mitigating risk is suggested when considering volunteer organizations. In fact, best results in risk mitigation can be achieved when a combination of control measures and strategies can be implemented (Herman & Chopko, 2009). To decrease the likelihood of risk, as well as minimize harm done, volunteer leaders should focus on the 4 Ps of risk elimination (position, person, physical environment, and performance management). The 4 Ps form the policies and protocols that will ultimately be used as risk control measures (Connors, 2012).

Position

Volunteer leaders must clearly articulate the roles and responsibilities of volunteer positions. Creating clear expectations will not only aid the volunteer in identifying if it is a good fit for them but also help the organization understand what positions are needed. Once the role of the volunteer is solidified, organizations then must decide the proper interviewing and screening methods to support the volunteer as well as the workplace culture. Each screening process will be dependent on the volunteer role and their expected level of interaction with clients and other confidential information (Cravens & Ellis, 2014).

Person

When considering the individual who is volunteering and the necessary personnel components that could aid in risk mitigation, volunteer leaders will again need to examine the type of volunteer activity that is requested. Volunteers working with children should complete a criminal background check (Cravens & Ellis, 2014). Depending on the type of activity, volunteer leaders might need to add skill-specific training for volunteers who need new skill sets to fulfill their volunteer role. Additionally, all volunteers should understand and be able to use the systems that are in place within the volunteer organization (Cravens, 2020).

Physical Environment

The organization’s physical environment is an important aspect to reduce and mitigate risk. Is the physical structure of a building and sidewalks up to code? Do all spaces meet accessibility requirements? Is the location safe for young children and youth? Additionally, an organization may have a virtual environment that must also be a focus of risk mitigation. While volunteers may not have a specific physical environment, it is important to set up online spaces and measures that protect the volunteers and clients. How do volunteers and clients communicate? How can outsiders in the program gain access to information? When considering online communication, especially interactions between volunteers and clients, the safest form of communication is a private communication system through “which all messages are sent, reviewed by staff before they can be read by the intended recipient, stripped of all personal identifying information by the moderator, archived for the record, etc.” (Cravens, 2020, para 5). However, this can make the experience less personal and may reduce trust and interpersonal relationships. Volunteer leaders must understand the goal and mission of the organization and balance the program goals with safety and risk management.

Performance Management

Volunteer leaders should examine how their interactions with volunteers enhance risk prevention (Connors, 2012). How can volunteer supervision and support aid risk measures and bolster performance? With a clear volunteer job description, volunteers should have expectations clearly defined. It is important to explicitly state what behaviors are unacceptable or inappropriate, the method of communicating appropriate behaviors to volunteers, repercussions of the behavior, and how the volunteer manager will be made aware of the behavior (Cravens, 2020). These guidelines will be based on the program goals, workplace culture, and systems within the volunteer role. Additionally, volunteer leaders should conduct an annual review of each volunteer’s activities to ensure the volunteer is not overcommitting and their volunteer work is of high quality. This annual review can also be used to revisit the organization’s expectations for volunteers and address issues, or potential issues, of volunteers who may be straying from the organization’s mission.

Step 4: Review

Review of identification and management strategies should be a continuous process that is integrated within the organization’s structure and systems. Volunteer leaders should view the risk mitigation process as ongoing because new volunteers bring forward potential new risks. Additionally, a risk previously designated as not harmful may change over time. The ongoing process should include regular policy review, building a risk management team, annual position appraisals, checking and maintaining equipment, and critically examining the risk control strategies. Ultimately, building a culture of risk management within the organization and program will allow volunteer managers to garner support, connect with volunteers, and increase safety measures. Volunteers will often aid in risk identification and can help with early detection and needed control measures.

Conclusion

Volunteerism has had an enormous effect on individuals, families, and society, as over 64 million Americans volunteer each year. Though volunteer efforts are needed and warranted, risk is always present within volunteer organizations (Connors, 2001). Utilizing the 4 Ps of risk elimination allow volunteer leaders to focus on the intricacies of their specific organizational needs. The volunteer position, person, physical environment, and performance management are all critical to developing and implementing risk control measures that will ultimately aid the organization in their overall success (Connors, 2012). Volunteer leaders that focus time and effort on risk management increase the overall success and health of the volunteer organization.

References

Connors, T. D. (2001). The nonprofit handbook (3rd ed.). John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Connors, T. D. (2012). The volunteer management handbook: Leadership strategies for success (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118386194

Cravens, J. (2020, April). Safety in virtual volunteering. Jayne Cravens Blog. http://coyotecommunications.com/coyoteblog/2016/07/vvsafety/

Cravens, J., & Ellis, S. J. (2014). The last virtual volunteering guidebook. Energize Inc.

Herman, M. L., & Chopko, M. E. (2009). Exposed: A legal field guide for nonprofit executives. Nonprofit Risk Management Center.

Independent Sector. (2022, February 3). Value of volunteer time. https://independentsector.org/value-of-volunteer-time-2021/