Introduction

The first publication in this series, The Use of Reflection as an Effective Leadership Practice: An Introduction, provided an overview of reflection as an effective leadership practice. Reflection is an important component of leadership, and developing a habit of reflection may lead to increased leadership effectiveness.

Johnson’s (2020) definition of reflection is relevant to leaders. He notes that “reflection is the intentional habit of creating space to think in order to pursue clarity of thought, learn from experiences and proactively advance ideas” (p. 23). Johnson identifies “what” leaders need to do: build intentional habits of creating space to think. He also indicates “why” leaders should reflect: to pursue clarity of thought, learn from experiences, and proactively advance ideas. However, this definition does not include the “how” of reflection. The purpose of this publication is to highlight models of reflection and demonstrate ways leaders can utilize frameworks to build reflective habits.

Reflection Models

Reflection is a tool in the leader’s toolbox to help them learn and make sense of the world around them. Peter Senge, an expert in organizational leadership, says “superior performance depends on superior learning” (Senge, 1990, p. 7). While there are many reflection models available, this publication will focus on two: Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle and the Borton Model of Reflection. These models were chosen to explore because of their straightforward nature and ability to be integrated into a leader’s busy schedule.

Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle

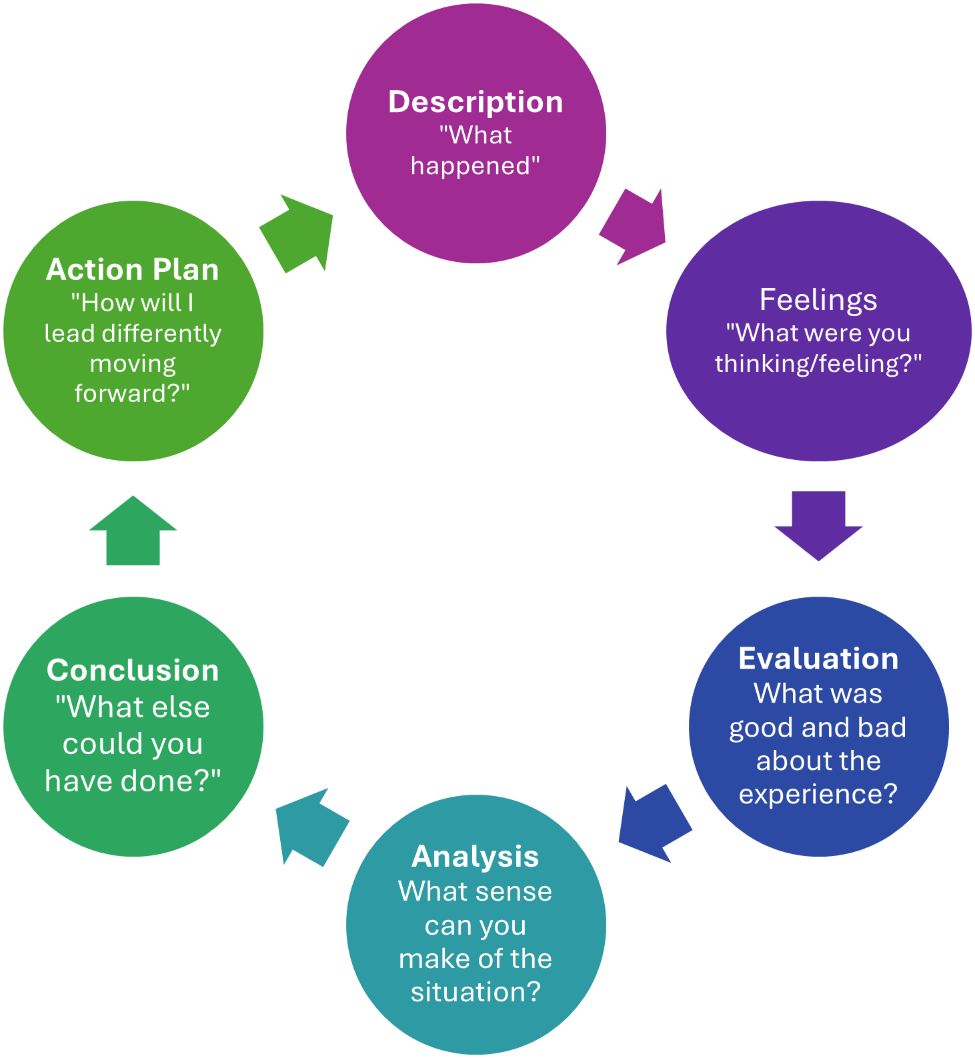

Graham Gibbs first outlined this reflective cycle in 1988. Gibbs expands on Kolb’s four-stage reflection model to include six stages of reflection. These stages are description, feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusions, and personal action plans (Gibbs, 1988). This reflection cycle can be processed through individual journaling, one-on-one coaching, or in a group setting with a facilitator.

- Description stage: In this stage, leaders should articulate what happened during the experience. The key element in this stage is to simply articulate what happened and avoid making assumptions or judgments about what was observed. Beginning with a factual account of the experience or event helps to remove emotions that may bias the ultimate reflection process.

- Feeling stage: During this stage, leaders name the feelings they had during or as a result of the experience. Again, at this point in the process, there should be no analysis of the feelings or judgments about the feelings. Naming how the leader felt about the experience continues to provide the foundation from which the reflective process can grow.

- Evaluation stage: During this stage, leaders can begin making initial value judgments about the experience. During this stage, they can determine what was “good” and “bad” about the experience. Additionally, they may expand this stage by considering what was challenging or seamless in the experience.

- Analysis stage: In this stage, leaders should begin the sense-making process of reflection. Leaders should begin considering why things happened the way they did, and what the causes and effects of the experience were. They should link past experiences or knowledge with the current experience to better understand the current situation (Praveena et al., 2025).

- Conclusions stage: In this stage, leaders begin to make conclusions from their evaluation and analysis stages. Conclusions should be both general and specific to one’s personal leadership. In this stage, leaders may ask themselves, “What could have been done differently,” and/or “How might this experience have been improved?” (Praveena et al., 2025).

- Action plan stage: In this final stage, leaders ask themselves, “What will I do the next time this situation occurs?” Additionally, leaders may consider, “Now that I have had this experience, how will I lead differently?” Determining next steps is critical to closing the reflection cycle. The action plan stage helps to solidify the new insights gained. If new insights are not gained, then true reflection has not occurred; rather, the leader has just spent time recalling the events. True reflection leads to new insights that in turn impact a leader’s future decisions.

Credit: Christy Chiarelli, UF/IFAS

Borton Model of Reflection

Terry Borton was an American schoolteacher who created a framework for reflection in 1970. This model has three primary questions: “What? So what? Now what?” (Borton, 1970). Due to its simplistic nature, this model may be advantageous for busy leaders. Even though there are fewer steps to this process, leaders should not shortcut the intentional reflection process.

- What? During this phase, leaders reconstruct the experience they want to reflect on. This phase combines Gibbs’ description, feelings, and evaluation stages. Questions to consider during this stage include, “What happened,” “What went well,” and “What went poorly?” (Haghighat et al., 2019).

- So what? The second phase encourages the leader to consider alternative action pathways that could be taken to prepare for similar situations in the future. This stage combines Gibbs’ analysis and conclusion stages by asking questions such as, “What was the outcome,” and “What did I learn from this situation?”

- Now what? This final phase asks the leader to apply the newly gained insight and knowledge to test the alternative action paths. This stage corresponds to Gibbs’ action plan stage by asking questions such as, “What do I need to do moving forward,” and “What changes will I make due to this new insight?” (Haghighat et al., 2019).

Conclusion

Reflecting on experiences is a well-accepted component for learning. However, one barrier to reflecting well is a lack of knowledge about the frameworks guiding the reflection process. The Gibbs Reflective Cycle and the Borton Model of Reflection are two such frameworks that leaders can apply even as the workplace becomes more complex and fast-paced. Through intentional use of reflection, leaders can gain new insights and increase their efficacy and productivity.

References

Borton, T. (1970). Reach, touch and teach. McGraw Hill.

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. London: FEU.

Haghighat, G. E., Hosseinichimeh, N., & Kleiner, B. M. (2019). Fundamental elements of reflective practice in organizations. IISE Annual Conference Proceedings, 32–37. Retrieved from https://login.lp.hscl.ufl.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/fundamental-elements-reflective-practice/docview/2511389643/se-2

Johnson, O. E. (2020). Creating space to think: The what, why, and how of deliberate reflection for effective leadership. The Journal of Character & Leadership Development, 7(1). Retrieved from https://jcldusafa.org/index.php/jcld/article/view/102

Praveena, K. S., Juslin, F., Chandrashekar, M. P., & Bhargavi, K. (2025). Using Gibbs’ reflective model approach for enhancing project-based learning among students through reflective assessment. Journal of Engineering Education Transformations, 38(2), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.16920/jeet/2025/v38is2/25018

Senge, P. (1990). The leader’s new work: Building learning organizations. Sloan Management Review, 32(1).