Large Carpenter Bees, Xylocopa spp. (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Apidae: Xylocopinae)

Introduction

In America north of Mexico, the subfamily Xylocopinae is composed of two genera, Ceratina (small carpenter bees) and Xylocopa (large carpenter bees). These bees get their common name from their nesting habits: small carpenter bees excavate tunnels in pithy stems of various bushes; large carpenter bees chew nesting galleries in solid wood or in stumps, logs, or dead branches of trees (Hurd and Moure 1963). The large carpenter bees may become economic pests if nesting takes place in structural timbers, fence posts, wooden water tanks, or the like. The genus Ceratina has 21 species in America north of Mexico, two of which occur in Florida (Daly 1973). Xylocopa has seven species in America north of Mexico, with two species found in Florida.

Credit: Paul M. Choate, UF/IFAS

Distribution

Xylocopa micans Lepeletier is known from southeastern Virginia down the East Coast of the US to Florida, west to Texas, and south to Guatemala. The typical form of Xylocopa virginica (Linnaeus) is known throughout the eastern United States southward to Texas and north Florida; the subspecies Xylocopa virginica krombeini Hurd is restricted to Florida from Sumter and Lake Counties south to Dade County (Hurd 1955, 1961).

Identification

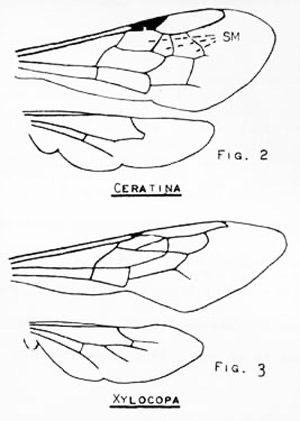

At various times, carpenter bees have been placed in the families Anthophoridae, Xylocopidae, and Apidae. Hurd and Moure (1963) traced the taxonomic history of these bees and found the most recent placement is within the Apidae (Krombein 1967). This family is characterized, in part, by the jugal lobe of the hind wing being either absent or shorter than the submedian cell and by the forewing having three submarginal cells. Within the family, carpenter bees are distinguished most easily by the triangular second submarginal cell and by the lower margin of the eye com- ing almost in contact with the base of the mandible (i.e., the malar space is absent).

The easiest method of separating Ceratina from Xylocopa is by size: Ceratina are less than 8 mm in length, whereas Xylocopa are 20 mm or larger.

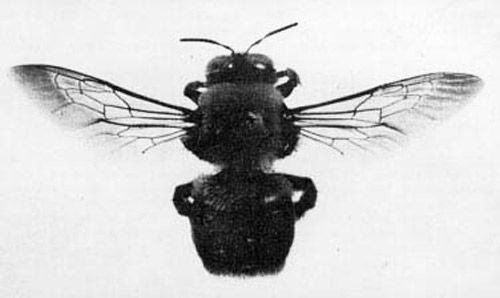

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Xylocopa generally resemble bumble bees in size and somewhat in color, being black, metallic bluish or greenish black, or purplish blue. Some males have yellowish areas on the face. Both sexes may have pale or yellowish pubescence on the thorax, legs, or abdomen, but these hairs are not as abundant or as intensely colored as in bumble bees. Large carpenter bees are readily distinguished from bumble bees primarily by the absence of pubescence on the dorsum of the abdomen, which is somewhat shiny. They also lack a malar space (present in bumble bees) and the triangular second submarginal cell. The two species of Xylocopa which occur in Florida are the only species in the eastern United States, namely Xylocopa micans Lepeletier and Xylocopa virginica (Linnaeus).

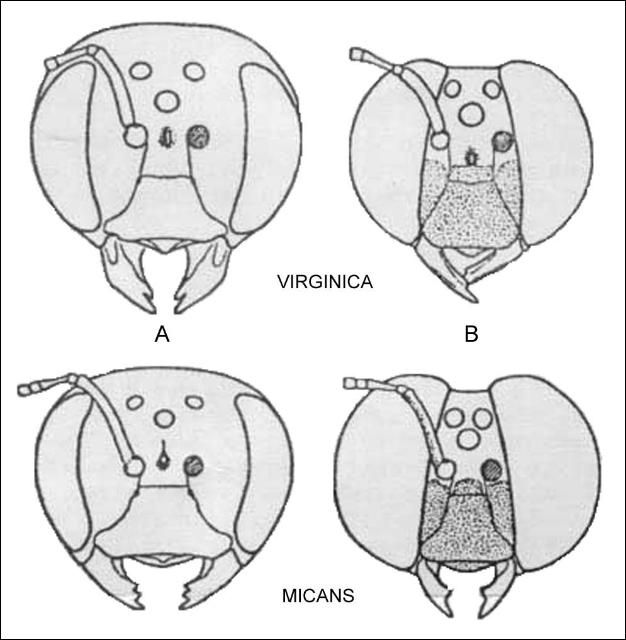

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

The two species of Xylocopa in Florida may be separated as follows:

1. Eyes nearly meeting above; antenna 13 segmented; abdomen 7 segmented (males) . . . . . 2

1'. Eyes widely separated; antenna 12 segmented; abdomen 6 segmented (females). . . . . 3

2. Abdomen metallic greenish blue; antennal scape yellow beneath; legs with patches of pale pubescence. . . . . micans

2'. Abdomen black with slight purplish tint; antennal scape completely dark; legs with dark pubescence . . . . . virginica

3. Thorax with dorsal and lateral black pubescence; body metallic purple. . . . . micans

3'. Thorax with dorsal and lateral pale pubescence; body mostly black. . . . . virginica

Credit: UF/IFAS

Biology

Xylocopa micans

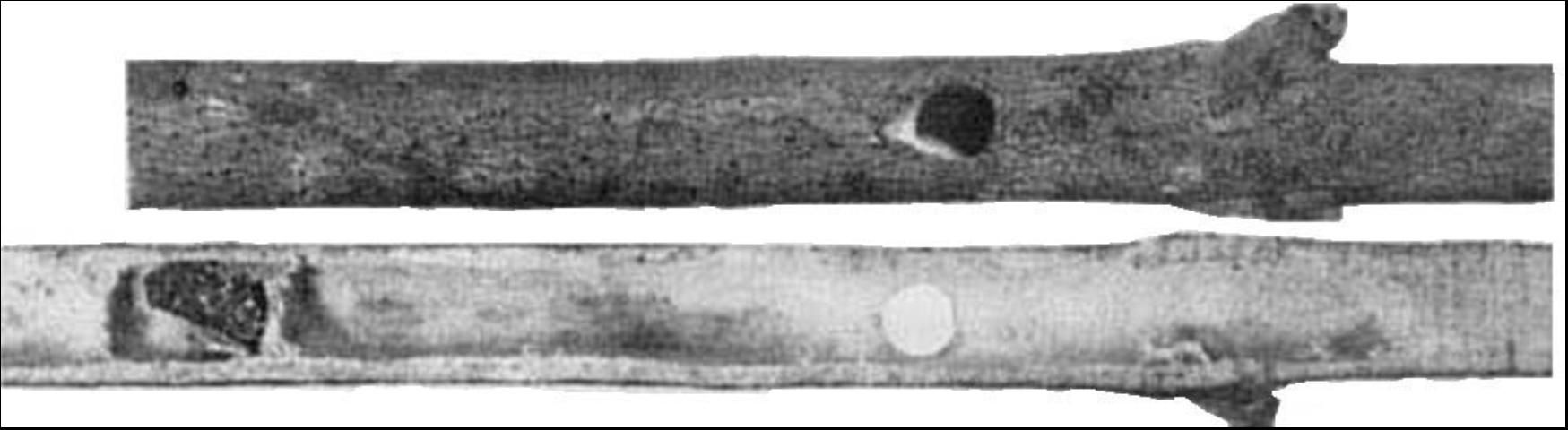

Little is known of the life history of this species. Hurd (1958) pictured a nest constructed in a dead Ligustrum branch. According to his report it was a sound twig with a diameter of 2.5 cm or more. The nest entrance was about 1 m above the ground, but entrances in other twigs were as low as 15 cm. The senior author found Xylocopa micans actively nesting in a red maple branch similar to the one reported by Hurd (1958). The twig was 1.6 cm in diameter near the nesting area and projected straight up from the ground. The entrance was approximately 1.5 m from the ground and was 8 mm in diameter. The lowermost, or first, brood cell was 12 cm below the nest entrance. Three cells had been constructed when the nesting activity was interrupted on 13 May 1975.

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Xylocopa virginica

Much has been written about this species: Rau (1933) provided one of the most complete accounts of its biology; Hurd and Moure (1963) cited many literature references; Balduf (1972) provided the most up-to-date summary of biology and literature; Sabrosky (1962) provided additional mating behavior.

The following account of life history is condensed from Balduf (1962): "Most reports indicate the use of dry, structural coniferous woods as nesting sites. Wood included Taxodium, Pinus, and Juniperus. Reports were also given for Magnolia planks and deciduous woods used in fence railings. Xylocopa virginica selects nesting sites in well-lighted areas where the wood is not painted or covered with bark. In general, these bees were gregarious, tending to nest in the same areas for generations. Old nests were refurbished, but new nests were also started. In new nests, female bees chewed their way into the wood, excavating a burrow about 15 mm in diameter. Boring proceeded more slowly against the grain (about 15 mm a day) than with the grain. The direction of galleries in the wood appeared to depend on the direction of the grain. If the grain were oriented vertically, the nests were vertical; if horizontally, then the nests were horizontal with respect to the ground. Galleries extended about 30 to 45 cm in newly completed nests. New tunnels were smooth and uniform throughout, but older galleries showed evidence of less uniformity with random depressions and irregularities. These older galleries were believed to have been used by several generations of bees. After excavating the gallery, female bees gathered pollen, which was mixed with regurgitated nectar. The pollen mass was placed at the end of a gallery (or bottom if the nest were vertical), an egg was laid, and the female placed a partition or cap over the cell composed of chewed wood pulp. This process was repeated until a linear complement of six to eight end-to-end cells was completed. Females apparently constructed only one nest per year in the North; bees emerged in the late summer and overwintered as adults with mating taking place in the spring. In Florida, however, Hubbard (in Howard 1892) reported at least two generations per year with broods in February-March and during the summer. Bees were active from November to January and from April to summer."

Economic Importance

Chandler (1958) lists four types of damage done by carpenter bees: weakening of structural timbers, gallery excavation in wooden water tanks (especially in arid western areas), defecation streaking on houses or painted structures, and human annoyance.The last point is included since carpenter bee females may sting (rarely), and male bees may hover or dart at humans who venture into the nesting area. In general, carpenter bees are not much of a problem.

Carpenter bees rarely attack painted or varnished wood. These bees often cause problems on structures by boring into the surface of the wood used as the back face of the trim under the eaves, as this surface is usually not painted. A buzzing or drilling sound is heard when the bee is boring into the wood. If the hole is not visible, often the case when the bee is boring into the backside of trim, look for sawdust on the ground under the hole.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Management

If problems do arise, use a small amount of insecticide that is labeled for bees and wasps: this can be dust, wettable powders, microencapsulated products, or aerosols. The labeled pesticide should be blown into the nesting holes.

This is more safely done with aerosols than with the other formulations. After a few days, the holes should be plugged with plastic wood, putty, or similar substance to allow the adult female to become exposed to the pesticide.

Selected References

Balduf, W.V. 1962. Life of the carpenter bee, Xylocopa virginica (Linn.). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 55: 263–271.

Borror, D.J., C.A. Triplehorn and N.F. Johnson. 1989. An Introduction to the Study of Insects. 6th Ed. Harcourt Brace, New York. 875 pp.

Chandler, L. 1958. Seven species of carpenter bees are found in the United States. Pest Control 26 (9): 36, 38, 40, 47.

Daly, H.V. 1973. Bees of the genus Ceratina in America north of Mexico. University of California Publication Entomology 74: 1–113.

Fasulo TR. Kern W, Koehler PG, Short DE. (2005). Pests In and Around the Home. Version 2.0. University of Florida/ IFAS. CD-ROM. SW 126.

Grissell, E.E. and M.T. Sanford. (December 2011). Small carpenter bees, Ceratina spp. EENY-101. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. http://entomology.ifas.ufl.edu/creatures/misc/ bees/ceratina.htm (June 2014).

Howard, L.O. 1892. Note on the hibernation of carpenter bees. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 2: 331–332.

Hurd, P.D., Jr. 1955. The carpenter bees of California. Bull. California Insect Survey 4: 35–72.

Hurd, P.D., Jr. 1958. Observations on the nesting habits of some new world carpenter bees with remarks on their importance in the problem of species formation. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 51: 365–375.

Hurd, P.D., Jr. 1961. A synopsis of the carpenter bees belonging to the subgenus Xylocopoides Michener. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 87: 247–257.

Hurd, P.D., Jr., and J.S. Moure. 1963. A classification of the large carpenter bees (Xylocopini). University of California Publication Entomology 29: 1–365.

Krombein, K.V. 1967. Apoidea. In Hymenoptera of America North of Mexico, Synoptic Catalog. Second Suppl. U.S. Department of Agriculture Monograph 2: 514–515.

Mallis, A. (ed.) 1990. Handbook of Pest Control. 7th Edition. Franzak & Foster Co. Cleveland. 1152 pp.

Mitchell, T.B. 1962. Bees of the Eastern United States. Vol. II. North Carolina Agriculture Experiment Statation Technical Bulletin No. 152: 1–557.

Rau, P. 1933. The Jungle Bees and Wasps of Barro Colorado Island. Privately printed, Kirkwood, MO. 324 pp.

Sabrosky, C.W. 1962. Mating in Xylocopa virginica. Proceed- ings of the Entomology Society of Washington. 64: 184.