Powdery mildew, Podosphaera aphanis (syn. Sphaerotheca macularis), occurs in most areas of the world where strawberries are grown.

Pathogen and Symptoms

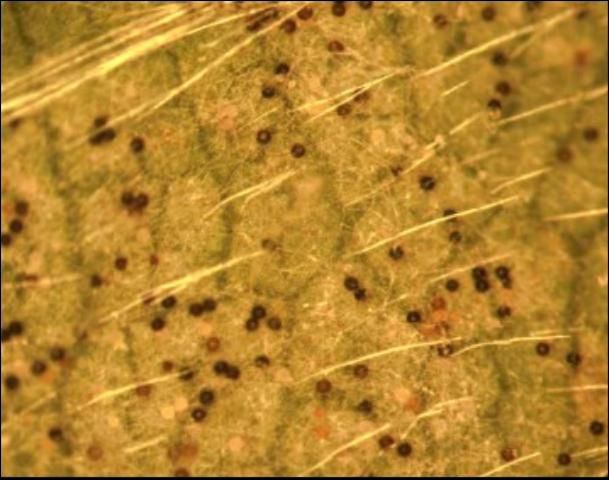

P. aphanis infects leaves, flowers, and fruit. Early foliar infections are characterized by small white patches of fungus growing on the lower leaf surface. On susceptible cultivars, dense mycelial growth and numerous chains of conidia (spores) give these patches a powdery appearance (Figure 1). Under favorable conditions, the patches expand and coalesce until the entire lower surface of the leaf is covered (Figure 2). In some strawberry cultivars, relatively little mycelium is produced, making it difficult to see the white patches. Instead, irregular yellow or reddish-brown spots develop on colonized areas on the lower leaf surface and eventually break through to the upper surface (Figure 3). The edges of heavily infected leaves curl upward (Figure 4). At times, dark round structures (cleistothecia) are produced in the mycelia on the undersides of leaves (Figure 5). Cleistothecia are initially white but turn black as they mature. The fungus also infects flowers, which may produce aborted or malformed fruit. In addition, P. aphanis colonizes older fruit, producing a fuzzy mycelial growth on the seeds (Figure 6). Both types of infection may reduce fruit quality and marketable yields.

Credit: UF/IFAS GCREC

Credit: UF/IFAS GCREC

Credit: UF/IFAS GCREC

Credit: UF/IFAS GCREC

Credit: UF/IFAS GCREC

Credit: UF/IFAS GCREC

Disease Development and Spread

P. aphanis is an obligate parasite that only infects living tissue of wild or cultivated strawberry. The fungus readily infects living, green leaves in the nursery. Thus, infected transplants are normally the primary source of inoculum for fruiting fields in Florida. When conditions are favorable, conidia produced on infected plants are wind dispersed. Powdery mildew development and spread are favored by moderate to high humidity and temperatures between 60°F and 80°F. Rain, dew, and overhead irrigation inhibit fungal development. The disease is typically more severe in plantings under greenhouse or plastic tunnels. In open fields in Central Florida, the disease is typically most severe in November and December, usually subsides in January and early February, but may reappear in late February and March.

Control

Using powdery mildew-free transplants would be a good method to control the disease, but these are difficult to find and even disease-free fields can become infected by conidia blown in from neighboring fields. Cultivars differ in their resistance to powdery mildew. 'Florida Radiance', and 'Florida Brillance' are moderately resistant whereas 'Sensation® Florida127' and 'Florida Beauty' are highly susceptible to powdery mildew. Fields with susceptible cultivars should be surveyed regularly for powdery mildew, especially early in the season. Fungicides should be applied preventively or at the first sign of disease to control powdery mildew on susceptible cultivars. This is especially important when using protectant fungicides, such as elemental sulfur. Systemic fungicides have some limited curative action. These include Quintec (quinoxyfen) and Torino (cyflufenamid), which have different modes of action and can be applied in alternation. Another group of products include Rally® (myclobutanil); Procure® (triflumizole); Orbit® (propiconazole); and Mettle (tetraconazole). These products are treated as a group since they belong to the same fungicide class and have similar properties. For this reason, they should be rotated with other fungicides with different properties to avoid the development of resistance. Other rotational options include Merivon® (pyraclostrobin + fluxapyroxad) and Fontelis™ (penthiopyrad). None of these products should be applied more than four times per season. Usually, controlling foliar infection helps to prevent fruit infection.