Trapping Wild Pigs: Techniques and Designs

Introduction

Wild pigs (Sus scrofa) are medium to large-sized (e.g., 150–220 lbs.) mammals with a stout body and a short, thick neck leading to a pointed head and flat snout. Wild pigs are also known by a variety of different names including feral swine, feral pigs, wild boar, and wild hogs. They often live in groups, called sounders, that typically consist of several generations of adult females and their offspring. Wild pigs are not native to the Americas and were first introduced by Spanish settlers in the 1500s. Genetically, wild pig populations in North America today can include feral pigs (wild descendants of the domesticated pigs brought by the Spanish), Eurasian wild boar (wild descendants of a domestic pig native to Eurasia), and hybrids of these two. Across North America, including Florida, wild pigs are invasive and can cause extensive damage to agriculture and a variety of ecosystems.

The most common type of damage to the natural environment caused by wild pigs is disturbed ground and destroyed vegetation from rooting. Swine burrow into the soil with their snouts to find roots, tubers, fungi, etc. This rooting loosens the soil, destroys native vegetation, and modifies the chemistry and nutrients of the soil. Wild pigs can harm not only natural ecosystems but also agricultural areas, livestock pastures, and even residential areas. Wild pigs also carry numerous pathogens, some of which are transmissible to wild and domestic animals as well as humans.

Wild Pig Control and Management

Controlling wild pig populations is difficult because of their high reproductive rate. Females can reproduce twice a year, with an average of 6–8 piglets in each litter. Many control techniques can be used, including hunting and trapping. Lethal control methods are the only way to effectively reduce the population of wild pigs. It is estimated that 66–70% of a wild pig population needs to be removed annually just to hold the population at its current level.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) legally defines wild pigs as wildlife but not a game species, although wild pigs are ranked the second most hunted mammal in Florida, after white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). It is important to understand the regulations for trapping, hunting, breeding, and moving wild pigs within Florida. On private property with landowner permission, wild pigs may be trapped and hunted year-round using any legal rifle, shotgun, crossbow, bow, or pistol with no size limit, bag limit, permit, or license required. However, it is illegal to transport or release wild pigs on public or private land, except under specific limited situations. To learn more about wild pig regulations in Florida, please visit https://www.fdacs.gov/Agriculture-Industry/Livestock/Animal-Movement/Swine-Movement-Requirements/Feral-Swine-Dealer-Application. Wild pig hunting is also offered on public wildlife management areas, where it is regulated by the FWC. To find out more about public hunting seasons, bag limits, and other regulations, please visit https://myfwc.com/hunting/wild-hog/.

Trapping Wild Pigs

Trapping and killing wild pigs from private property is an effective way to reduce or control local wild pig populations (Figure 1). There is strong evidence that removing the entire sounder of wild pigs, instead of individuals or partial groups, is the most effective way to reduce wild pig populations and control damage. This removal is often achieved with a trap that can capture the whole sounder, followed by humane dispatch in the trap. Hunting and other methods that do not remove the whole sounder are less effective because uncaptured or escaped wild pigs are educated of the danger of the traps and will be more difficult to trap in the future. This publication describes commonly used trapping techniques, traps, and gate designs. Several factors contribute to successful trapping of wild pigs, including:

- Identifying areas used extensively by wild pigs and focusing your trapping in those areas

- Pre-baiting to allow wild pigs to become accustomed to the food source you provide

- Choosing effective trap types and gate designs to match the number of wild pigs you anticipate catching

- Placing bait in the proper location within traps

- Monitoring traps and adjusting your technique as needed

- Maintaining patience and persistence

Game cameras will allow you to adjust your trapping techniques as needed for successful wild pig trapping. They can monitor your traps for wild pig presence and help with troubleshooting. Game cameras will let you know whether your problem is trap-shy wild pigs (who have learned to be wary of traps), a faulty trap door or trigger, non-target species triggering your trap, or some other issue. Game cameras will also allow you to count the number of wild pigs in the sounder so you will know if you captured the entire sounder or not.

Credit: Jesse Lewis, Arizona State University

There are four basic trap types: box traps, cage traps, corral traps, and silo traps. There are also several gate and trigger options that can be used with each trap type. You should choose a trap and gate type that is most efficient and cost effective for your needs. Some things to consider when managing wild pigs by trapping include:

- Density of wild pigs in the area and typical sounder (group) size

- Your budget

- Portability and weight of the trap (if you need to move it)

- Presence of non-target species that could be captured in the trap

- Number of traps needed

- Wild pig management efforts being conducted by your neighbors or agencies

Choosing Trap Locations

When choosing locations for trapping wild pigs, look for signs of wild pig activity, including evidence of rooting, tracks, and wallows, and then look for a nearby area with shade and water. Sites where wild pig foraging has caused damage reveal that wild pigs are in the area, but these areas may not actually be the best places to put traps because wild pigs spend most of their time in shaded areas close to a water source (Figure 2 and 3). It is best to scout nearby low-lying areas such as river or creek bottoms, wetlands, and forest edges. Travel routes to and from these areas are ideal for higher catch opportunities. Setting traps at multiple sites may also increase your success. Keep in mind that vehicle access to traps is usually essential for loading and unloading traps, baiting them, and removing dispatched wild pigs. You will also want to consider public safety by ensuring your trap site is not easily accessed by other people.

Credit: Raoul Boughton, UF/IFAS

Credit: Raoul Boughton, UF/IFAS

Pre-Baiting and Baiting

Pre-baiting the trapping area before you set up the trap attracts wild pigs to a location and gets them accustomed to a new food source (bait). Game cameras focused on the bait pile will let you monitor their activity, and you can count how many pigs are in the group you are targeting. Try to limit your visits to the trapping area, but do not allow the bait to run out, otherwise the pigs might move on. Once the wild pigs have learned where to go for food, you can introduce the trap. Erect the trap in the spot where you have been pre-baiting, secure the door of the trap in an open position. Do not set the gate/trigger; the goal is to allow the pigs to enter and exit the trap. Create a bait trail into the trap. Monitor the trap(s) with game cameras to ensure wild pigs are readily entering the trap(s) for at least three nights. When wild pigs are entering regularly, set the trap trigger and bait along the inside of the trap leading to the trigger location. Also put bait on the trigger (Figure 4). Baiting along the sides of the trap leading to the trigger will allow more wild pigs to enter the trap before the mechanism is triggered. Common baits include dry or fermented corn, vegetable/produce scraps, molasses, red Kool-Aid ® or gelatin powder, and commercial attractants.

Credit: Wesley Anderson, UF/IFAS

Common Reasons for Poor Trapping Success

- Bad trap placement: Remember travel routes to and from shaded areas or water sources are typically more successful than sites of rooting damage.

- Excessively brief pre-baiting period: Monitor with game cameras, but pre-baiting may require up to 2 weeks, especially for trap-shy pigs.

- Faulty trigger: Be sure to test your trigger multiple times before leaving a trap set. To trap a large sounder of wild pigs, a looser (harder to trip) trigger will allow more pigs to enter the trap before the trigger is tripped. For trap-shy wild pigs, you may want to try a tighter (easier to trip) trigger to ensure the pig is caught. Wild pigs can climb or jump and escape from traps with short walls or panels. Jump bars or walls/panels at least 5 feet high and round corral traps without corners will reduce the risk wild pigs will escape your trap.

- Abundant natural food: When acorn mast, other natural foods, or supplemental foods like minerals or molasses intended for livestock are abundant, you may have lower success trapping wild pigs.

- Hunting and dogs in the area: These factors can make wild pigs more wary and reduce trap success.

- Gates closed too early: Trap gates that close before all adults in a sounder are caught can leave wild pigs educated and hard to trap in the future. Sometimes this is caused by a trigger that is too tight (springs too easily, before all the pigs in the group have entered the trap). Game cameras can help you monitor the behavior of wild pigs on your property and adjust your trapping techniques accordingly.

Types of Traps: Designs and Costs

Portable Wooden Box Trap

A relatively cost-effective trap that is ideal for capturing individual wild pigs or small groups of wild pigs (Figure 5).

Credit: Mississippi State University Extension

- Made of treated lumber or wood fence panels.

- Typically rectangular, 4 feet wide, 8 feet long, but can sometimes be square. At least 5 feet high, with no top.

- 5-foot height prevents wild pigs from climbing or jumping out.

- Usually heavy enough to prevent lifting by wild pigs. If not, T-posts can be added to prevent wild pigs from lifting trap sides and escaping underneath.

PROS

- Simple to construct

- Cost effective

CONS

- Capable of capturing only a small number of wild pigs

- May appear confining to trap-shy wild pigs

- Heavy; may require several people to assemble and transport

- May require long-term maintenance

Table 1. The cost of a portable wooden box trap for wild pigs.

Portable Cage Trap

A stronger portable trap that is ideal for capturing individual or small groups of wild pigs (Figure 6).

Credit: Jesse Lewis, Arizona State University (left) & Randy Kelley, The Hawg Stopper LLC (right)

- Typically, 4 feet wide, 6–12 feet long, and 4–5 feet high.

- Traps less than 5 feet tall should have a top panel or jump bars to prevent wild pigs from jumping or climbing out.

- A new round design can be rolled, which makes this style trap easier to transport than a square or rectangular design.

PROS

- Can be constructed relatively easily, also available for purchase with little assembly required

- May appear more open to trap-shy wild pigs

- Easy to store, transport, and relocate

CONS

- May be capable of capturing only a small number of wild pigs

- More expensive

PURCHASING INFORMATION

There are multiple vendors of cage traps. See examples below.

- Voorhies Outdoor Products, LLC hog trap—Metal trap with 3 rooter doors

- 8’ by 4’ by 3’

- $400

- The Hawg Stopper, LLC hog trap, aportable round trap with guillotine gate

- For pricing contact 870-574-1824 or thehawgstopper@hotmail.com

Note: The University of Florida and UF/IFAS do not endorse any company or trap type.

Corral Trap

An effective trap for capturing large groups of wild pigs (Figure 7).

Credit: Mississippi State University Extension Service

PROS

- Very effective for trapping large groups

- Allows most non-target species to escape

- Open appearance may appear less threatening to trap-shy wild pigs

- Where wild pigs densities are high, the trap can be used long term. You can build the panel structure and move the doors to different panel locations depending on wild pig activity.

CONS

- Requires more time and effort to construct.

Table 2. The cost of a corral trap for wild pigs.

Silo Trap

A cost-effective trap that allows for the capture of large groups of wild pigs. It allows design flexibility and can be used with a variety of funnel type gates (Figure 8). The trap is constructed from either continuous mesh panel or multiple livestock panels fastened to 6.5’ T-posts using U-bolts and cable clamps. The ends of mesh panels can be constructed to serve as a funnel in which wild pigs must push through to enter a trap. Tines on the edges of mesh panel entry will prevent wild pigs from pushing back out. Traps should be at least 5 feet tall to prevent wild pigs from climbing or jumping out. It is also recommended to add jump bars or wire across the top to prevent wild pigs from escaping.

Credit: Jim Mitchell, feralfix.com.au

- Flexibility in shape and size allows a variety of possibilities to suit needs or materials on hand.

- Can vary in shape but are typically round to prevent wild pigs from piling up in corners and possibly climbing or jumping out.

- The funnel entry reduces the costs of building or purchasing a gate.

PROS

- Easy to store, transport, and relocate

- Cost effective

- Flexibility in design, shape, size, and funnel used (Figure 9)

CONS

- Catch capability depends on size

- More effort to construct or relocate

Credit: UF/IFAS

Table 3. The cost of a silo trap for wild pigs.

Mesh Trap

A cost effective, lightweight and portable mesh trapping system. The trap is constructed from a mesh base trap net connect to t-posts that allows pigs to push under the net to enter the trap but does not allow them to exit (Figure 10).

Credit: Pig Brig trapping Systems, https://pigbrig.com/

PROS

- Very effective for trapping large groups

- Lightweight

- Open appearance may appear less threatening to trap-shy wild pigs

CONS

- May get torn and need repairs

- Requires time and effort to set up

*Pig Brig Trapping System costs approx. 1,995 (t-post not included)

* pigbrig.com or 1-833-PIG-BRIG

Gate Types

There are many variations in design and materials used for trap gates. Most are made from steel or wood. Your gate choice depends on your budget, ease of transport, and the trap type. Gates can be either single catch (once triggered, no additional wild pig may enter the trap) or multi-catch (wild pigs may continue to enter the trap after the first wild pigs have entered). The four basic gate types are:

- Drop or guillotine gate – This gate is inexpensive and easily constructed. The gate is suspended by a trigger line. Once triggered, the gate will drop closed. Single catch (Figure 11A).

- Swing or saloon gate – This gate pivots toward the inside of the trap and is held with a trigger line. Once triggered, heavy springs close the gate quickly; however, pigs can continue to enter after the gate has closed. If the gate is not padded, it can be noisy and frighten other wild pigs. Multi-catch (Figure 11B).

- Rooter or lift gate – The hinged top of this gate allows one-way entry into a trap. It can also be set open and then drop closed with a trigger. If it is not padded, this gate can be noisy and frighten other wild pigs. Multi-catch (Figure 11C).

- Funnel entry – The ends of mesh panels can be constructed to serve as a funnel wild pigs must push through to enter a trap. Tines on the edges of the mesh panel entry will prevent wild pigs from pushing back out. A benefit is the quiet closure. Multi-catch (Figure 11D).

Credit: (A) Joe Halseth, USDA; (B) Mississippi State University; (C) UF/IFAS; (D) Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service

Trigger Mechanisms

Two types of trigger mechanisms may be used when trapping wild pigs: a rooter stick and a trip wire. For both, the trigger is released when a pig inside the trap contacts it while feeding, and the trigger pulls a line that is attached to the gate door, which causes the gate to fall or swing closed.

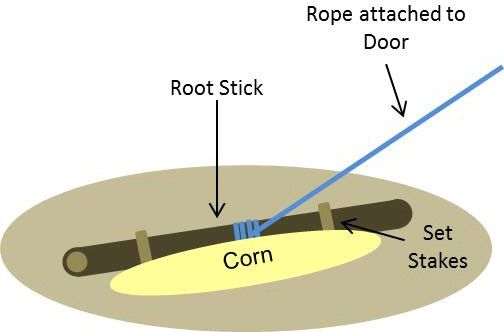

Rooter Stick

A stick is wedged beneath two holding stakes in or around a bait pile (Figure 12). The stick is triggered when the wild pigs feed and root around, pushing the rooter stick out from under the holding stakes. The stick is supporting the weight of the gate. When wild pigs dislodge the stick, they trigger the gate to close.

Credit: UF/IFAS

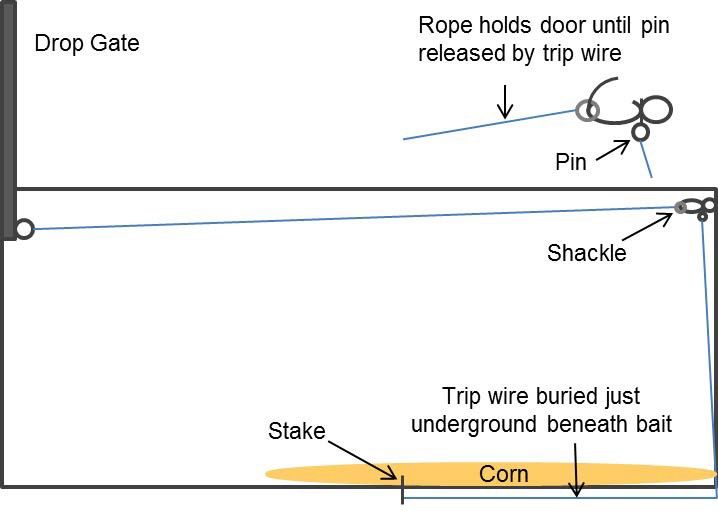

Trip Wire

A line or wire is buried under bait or suspended slightly above the ground, attached to a triggering device like a pin or a shackle that will release the gate when pressure is exerted on the line (Figure 13 and 14). Many different designs are possible.

Credit: UF/IFAS, Design by USDA Wildlife Service

Credit: UF/IFAS, Design by USDA Wildlife Service

“Smart” Traps

Smart traps have a remote-triggered gate and cameras that allow you to wirelessly monitor your traps to catch entire sounders or large groups of wild pigs at the same time. Below are several examples of vendors and their products.

Jager Pro M.I.N.E™ Trapping System (Manually Initiated Nuisance Elimination)

- Uses a large corral trap (35’ diameter) and an 8’ gate closed by a remote-control device. Trap is monitored with a wireless camera that can send pictures and videos to your phone or email (Figure 15).

- MINE camera with live feed costs approx. $1,300

- Gate and camera costs approx. $3,000

- Entire M.I.N.E. Trapping System costs approx. $5,725

- https://jagerpro.com/ and http://www.floridaferalhogcontrol.com

Credit: Photo courtesy of Jager Pro

BoarBuster—The Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation

- Uses a large corral trap that is suspended above the ground and then remotely triggered to drop over the entire group of wild pigs. Trap is monitored with a wireless camera that can send pictures and videos to your smartphone or email (Figure 16).

- Next Gen 4G BoarBuster Trapping System costs approx. $6,995

- With color HD approx. $7,995

- Distributed by W-W Livestock Systems

- sales@boarbuster.com or 855-751-7980

Credit: Boarbuster – Noble Foundation

Humane Trapping and Euthanasia

Although wild pigs are an invasive species, they are living animals that register pain and stress. Steps should be taken to minimize stress and ensure they are treated humanely when trapped and euthanized.

Humane Trapping

- Traps should be checked at least once daily and placed somewhere with shelter or shade.

- Traps should be constructed to minimize injury. Small mesh size should be used to avoid snout injury (suggest 2” x 4”, but 4” by 4” is the minimum recommendation).

- Traps should be secured so that wild pigs cannot lift the trap.

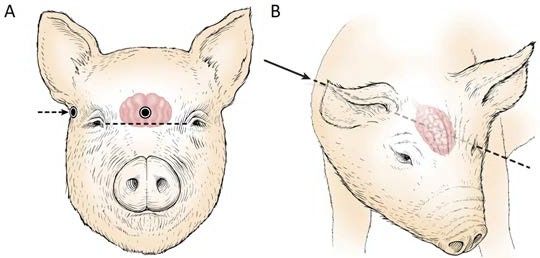

Humane Euthanasia

- Wild pigs should be euthanized quickly. The shooter should approach the trap quietly to avoid panicking the trapped wild pigs.

- Wild pigs can be euthanized using a .22 caliber rifle or larger.

- Do not insert the rifle barrel into the trap through the side panels because wild pigs may charge and hit the barrel, potentially causing you or someone else injury. Instead, shoot through the panels or down into the trap from above.

- Two possible sites to ensure a quick, humane brain shot:

- Frontal shot – center of the forehead, placed about 2–3” above an imaginary line directly between the eyes and aimed toward spine. (Figure 17A)

- Oblique shot – from behind the ear and aimed towards the opposite eye (Figure 17B)

- Be careful not to shoot directly between the eyes. A shot fired between the pig’s eyes will hit the nasal cavity, not the brain, and it will not immediately kill the pig. To avoid injury, you should not enter the trap until you have ensured that all wild pigs have been euthanized

*Note: Wild pigs carry many diseases that are potentially harmful to humans. Make sure to protect yourself by wearing gloves and other safety equipment when handling live or dead pigs. To learn more about pig diseases and contact resources visit: https://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/health/feral-swine/swine-brucellosis/ and https://www.cdc.gov/brucellosis/exposure/hunters.html.

Credit: J.K. Shearer and A. Ramirez, http://vetmed.iastate.edu/

Additional Resources and Information

Hamrick, Bill, Mark Smith, Chris Jaworowski, and Bronson Strickland. 2011. A Landowner’s Guide for Wild Pig Management: Practical Methods for Wild Pig Control. Mississippi State University Extension Service & Alabama Cooperative Extension System. Available at https://extension.msstate.edu/sites/default/files/publications/publications/p2659_0.pdf

Mayer, John J., and I. Lehr Brisbin Jr. Wild Pigs: Biology, Damage, Control Techniques and Management. Savannah River National Laboratory, Aiken, NC. Available at https://sti.srs.gov/fulltext/SRNL-RP-2009-00869.pdf

Shearer, J. K., and A. Ramirez. 2013. Humane Euthanasia of Sick, Injured and/or Debilitated Livestock. Iowa State University Extensions. Available at https://vetmed.iastate.edu/sites/default/files/vdpam/Extension/Dairy/Programs/Humane%20Euthanasia/Download%20Files/EuthanasiaBrochure20130128.pdf

VerCauteren, Kurt C., James C. Beasley, Stephen S. Ditchkoff, John J. Mayer, Gary J. Roloff, and Bronson K. Strickland. 2020. Invasive Wild Pigs in North America: Ecology, Impacts, and Management. CRC Press. Available at https://doi.org/10.1201/b22014

West, Ben C., Andrea L. Cooper, and James B. Armstrong. 2009. “Managing Wild Pigs: A Technical Guide.” Human Wildlife Interactions Monograph 1:1–55. Available at https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=hwi_monographs