We created this publication for UF/IFAS Extension, health educators, health care providers, and other community members who want to help build confidence in and engage members of the public around adult vaccination. We created this series of publications in response to both the COVID-19 pandemic and rising concerns over decreased vaccine uptake rates. This first document in the series provides an overview of expert medical perspectives towards recommended vaccinations for adults in Florida as well as areas of recognized disparities.

Educators interested in helping Floridians understand and access vaccines may have varying expertise, including those who are deeply connected to and rooted in their communities but who may not have formal health care backgrounds and educators who are versed in speaking with communities who may also not have formal health care backgrounds. Therefore, we discuss both background on the importance of vaccinations for adults in the U.S. and particular understanding of Florida adult vaccination rates and priority populations to work with to build health equity. Two companion publications (Katsaras et al., 2024; Stofer et al., 2024) offer more in-depth background on reasons for lower vaccination uptake and outline resources and strategies to build vaccine confidence and encourage vaccination among Florida adults, respectively.

Credit: Adobe Stock Image

The Importance of Building Vaccine Confidence

Regardless of the advancements in vaccine development due to modern medicine, adult vaccination rates continue to be substandard. Building adult vaccine confidence remains a crucial issue for many global health organizations (Akbar, 2019). Any decrease in the immunization rate can have devastating impacts on the herd immunity that many people rely on to prevent the spread of disease (Jacobson et al., 2015). Raising vaccination rates could result in a decrease in deaths from disease due to direct and indirect prevention (Hunter et al., 2020). By ensuring that adult vaccination rates increase, we can minimize the impact and spread of preventable illnesses.

The need for adult-focused vaccination education has become apparent in recent years as fewer adults are fully immunized. Adults need to exhibit vaccine confidence and initiative, beyond their role as parents vaccinating their children. While there is a surplus of information on the need to provide children with their initial vaccinations, this tends to divert attention away from adult vaccination schedules. There is extensive legislation and political focus on raising childhood immunization rates, yet there has never been a program in the United States to encourage general adult vaccinations beyond targeted responses to a specific pandemic, such as the COVID-19 programs (Roper et al., 2021). Strong vaccine recommendations from health care providers are shown to increase corresponding vaccine coverage (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). It is evident from the factors contributing to vaccine hesitancy that there is no one way to recommend vaccination; rather, it is more important to craft an individualized approach based on the patient’s social, economic, and cultural background and specific circumstances.

The Role of Health Extension and Health Education

Extension has a long history of working in preventive health across all our focus areas, such as farmworker safety, homeowner and resident well-being, and natural resources preservation for mental well-being. The latest National Extension Framework for Health Equity and Well-Being (Burton et al., 2021) focuses on building equity through addressing both systemic and individual health, both through improving social factors and connecting people to education and health care. Extension, via the Extension Foundation, began national efforts to include adult vaccine efforts in our Extension programming with the onset of COVID-19, but going forward will continue work on all types of recommended vaccination, including flu, tetanus, shingles, and more.

If you are new to health education or specifically vaccine education, engaging communities around adult vaccinations may be uncomfortable, especially if you feel you lack expertise in either vaccines or communication when people may push back. You are not alone in that discomfort; across the nation, many Extension educators who participated in a survey as part of the Extension Collaborative on Immunization Teaching and Engagement (EXCITE) expressed several reasons for their own reluctance to engage in this work when it was catalyzed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many Extension directors supported the work, but many agent respondents felt low confidence in doing the work.

We in Extension and health education get overwhelmed, and so do public health officials. Therefore, partnering in these efforts can help to share the load. Educators might not be able to administer vaccinations, but we can help build confidence and refer people to care and resources. Incomplete health insurance coverage, whether through lack of coverage or holes in coverage, is an issue in the U.S., with approximately 10% of adults under 65 lacking coverage when interviewed in 2021 (Cha & Cohen, 2022). Many people rely on their doctors for vaccine information (Katzman & Christiano, 2022), but if they do not go to doctors even for annual checkups, they might be missing information on regular recommended vaccines. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) did not have a concerted comprehensive adult vaccination education program prior to 2020. Extension can support health care providers by sharing educational resources, and health care providers can refer patients to Extension for supportive care and community resources. Importantly, connecting people to resources to support their whole health, including access to food, housing, and other urgent medical care, can be a way to support equity and make immunization a part of improving health holistically. Finally, a large obstacle is the public’s hesitancy to vaccinate due to various demographic and psychographic influences, results, and levels of resistance. Extension can build trust in vaccines through sustained community work addressing these areas.

Overcoming Vaccine Hesitancy and Building Confidence

The World Health Organization defines vaccine hesitancy as “the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines” (Akbar, 2019). Low vaccine confidence, or hesitancy, is becoming an epidemic, as vaccine uptake rates for adults in the United States remain suboptimal. Many sources attribute vaccine hesitancy to the neglect of adult vaccinations (Nowak et al., 2017). The U.S. has focused on initial vaccines, typically during childhood, but many adults are unaware that they must continue to update their vaccinations to maintain a fully immunized status (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). Every adult has a recommended vaccination schedule based on their age, medical conditions, and specific circumstances (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). Failure to stay up to date on vaccinations exacerbates a global issue because cases of vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles and human papillomavirus increase (Akbar, 2019). More well-known diseases tend to capture the attention of the media and the focus on adult vaccinations.

However, the reasons behind low vaccine uptake are complex and influenced by a variety of factors ranging from demographic to psychographic backgrounds. Three major concepts intertwine to influence acceptance and uptake: confidence, complacency, and convenience. Respectively, these cover ideas of trust in effectiveness and safety of vaccines, feeling low urgency or threat from the illness itself, and physical accessibility and insurance availability for vaccines. We detail these concepts, their importance in different communities, and ways to address these factors in the companion publications (Katsaras et al., 2024; Stofer et al., 2024). Less-than-ideal adult vaccine rates may become a more pressing issue if these barriers remain.

The Florida Situation

The Florida Department of Health and associated county departments offer the most localized information on vaccination rates for various vaccines (e.g., the flu vaccine) with its weekly Florida Flu Review tracker and annual reports, which can be found on the FloridaHealth.gov website. The CDC collects annual data on immunization coverage among adults through the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, with specific questions on COVID-19 vaccinations among adults collected through the National Immunization Survey. Florida-specific and COVID-19 vaccination rates broken down by age, rural/urban residence, and gender, including rates for the Fall 2023 vaccination dose, can be found at COVIDVaxView under the monthly and weekly reports.

The CDC releases annual maps of state and county levels of flu vaccination, available by age and some race/ethnicity data, at least at the end of the previous season, and with available trend data over the past several years. View the maps and download the data at sites such as FluVaxViewer and AdultVaxView for even more vaccinations.

Rural Residents as a Priority Population

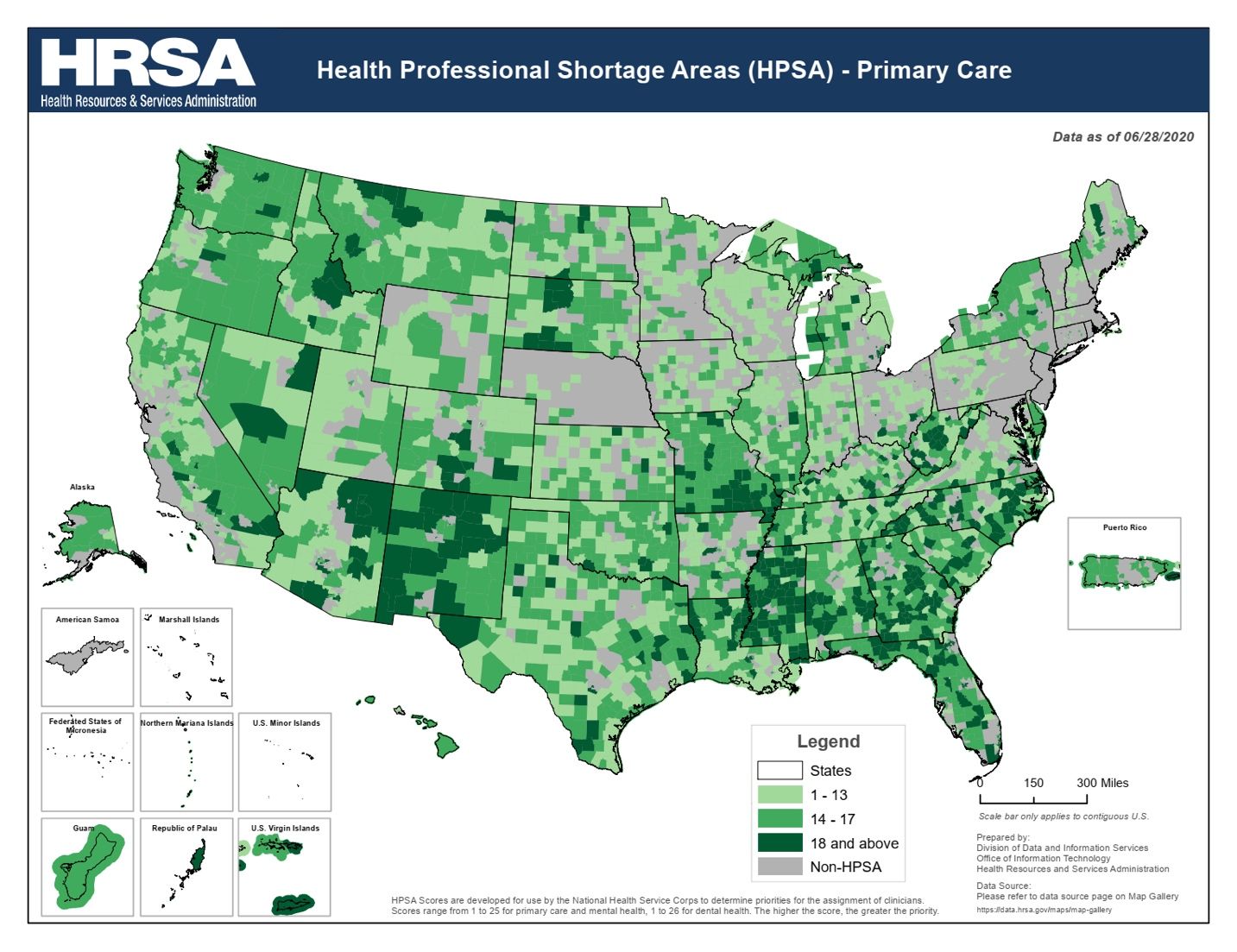

Approximately 700,000 of Florida’s 21 million residents, or about 3%, are classified as rural residents. On the other hand, approximately one-third of our 67 counties are nonmetropolitan, especially in the Panhandle area and north central Florida, with a few in the peninsula south of Orlando and away from the coast. Access to health care and other infrastructure are important facets of social determinants of health, or factors in the environment that impact health outcomes (Burton et al., 2021). Rural residents often have less access to such infrastructure, which can have direct and indirect impacts on their vaccination rates. Primary care doctors are often trusted sources of information, but many rural residents face shortages of primary care doctors. Figure 2 displays a map of health professional shortage areas (HPSA).

Credit: Division of Data and Information Services, Office of Information Technology, Health Resources and Services Administration

Historically, rural residents have lower vaccination rates and generally poorer health metrics; however, these gaps compared to urban residents vary in size across particular vaccinations as well as demographics. Rural residents in Florida have higher poverty rates than their urban counterparts, presenting further barriers to immunization.

Recommendations

- First and foremost, listen to priority populations to understand their needs. Gather feedback at every stage of your program to make sure you continue to be responsive to the population’s concerns.

- Given the recent politicization of vaccinations, consider embedding vaccination into a whole health education approach, rather than as a stand-alone effort.

- Consider ways to facilitate administration of vaccines through partners. For example, encourage families or friend groups to get vaccinated together.

- Plan vaccination and health education efforts to be a year-round ongoing campaign with emphasis on seasonal vaccines as infection season approaches, such as with National Immunization Awareness Month in August.

- Even in some communities where Extension and other health educators have long-standing relationships and programs on adult health, educators may find that vaccination education is a challenge requiring additional work on buy-in from partner organizations before education efforts can begin. Collaborate and work with existing and new partner health care provider organizations in order to complement any ongoing efforts they have in education and to build on trust they may have with communities.

- Remember that communities vary even within specific identity groups. Therefore, community engagement principles are key (Stofer, 2017).

Our Ask IFAS publication on factors preventing adult uptake of vaccinations (Katsaras et al., 2024) more thoroughly reviews reasons people decline or postpone recommended vaccines. Another accompanying publication by Stofer et al. (2024) provides in-depth recommendations and further resources for promoting adult vaccination for both seasonal and one-time immunizations.

Conclusion

While there may be less information on confidence in vaccines specifically for adults than for children, information does exist on confidence in the health care system and/or cultural norms about health care use. This information might also inform your work, but may be outside of the scope of this article. Examples include works by Jack (2021), Kowitt et al. (2017), and Simmons-Duffin (2021). In addition, work about COVID-19 vaccines and confidence is likely still to emerge in the next few years.

In general, validating feelings, approaching from a stance of listening, understanding, and care, and supporting health, values, and needs can work for many situations. It is important to consider the patient’s background in your discussion. The companion publications by Katsaras et al. (2024) and Stofer et al. (2024) provide specific strategies for communication and resources meant to build confidence and, ultimately, health equity.

Resources

The USDA Economic Research Service publishes regularly updated Florida rural and urban population facts.

Consult the CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, State Contacts.

The Brookings Institution podcast series, Reimagining Rural, features rural towns experiencing positive changes.

Through the Immunization Section, Division of Disease Control and Health Protection, Bureau of Epidemiology, FLDOH offers vaccines for adults who are uninsured or underinsured through the Vaccines for Adults program.

The CDC publishes Annual Vaccination Coverage Reports for flu, and sometimes other, vaccinations, specifically addressing adult vaccination.

References

Akbar, R. (2019). Ten health issues WHO will tackle this year. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

Burton, D., Canto, A., Coon, T., Eschbach, C., Gunn, J., Gutter, M., Jones, M., Kennedy, L., Martin, K., Mitchell, A., O’Neal, L., Rennekamp, R., Rodgers, M., Stluka, S., Trautman, K., Yelland, E., & York, D. (2021). Cooperative Extension’s National Framework for Health Equity and Well-Being [Health Innovation Task Force]. Extension Committee on Organization and Policy. https://www.aplu.org/wp-content/uploads/202120EquityHealth20Full.pdf

Cha, A. E., & Cohen, R. A. (2022). Demographic Variation in Health Insurance Coverage: United States, 2021 (National Health Statistics Reports No. 177). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr177.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Resources for educating adult patients about vaccines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/adults/for-patients/index.html

Hunter, P., Fryhofer, S. A., & Szilagyi, P. G. (2020). Vaccination of Adults in General Medical Practice. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(19)30310-6/fulltext

Jack, L. (2021). Advancing Health Equity, Eliminating Health Disparities, and Improving Population Health. Preventing Chronic Disease, 18. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.210264

Jacobson, R. M., Sauver, J. L. S., & Rutten, L. J. F. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(15)00719-3/fulltext

Katsaras, A. V., Stofer, K. A., O'Neal, L., & Yates, H. (2024). Factors Preventing Widespread Vaccine Uptake among Adults: Adult Vaccination in Florida. EDIS.

Katzman, J. G., & Christiano, A. S. (2022). Clinicians as Trusted Messengers—The “Secret Sauce” for Vaccine Confidence. JAMA Network Open, 5(12), e2246634. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.46634

Kowitt, S. D., Schmidt, A. M., Hannan, A., & Goldstein, A. O. (2017). Awareness and trust of the FDA and CDC: Results from a national sample of US adults and adolescents. PLOS ONE, 12(5), e0177546. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177546

Nowak, G. J., Shen, A. K., & Schwartz, J. L. (2017). Using campaigns to improve perceptions of the value of adult vaccination in the United States: Health communication considerations and insights. Vaccine-Science Direct. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X17311623?via%3Dihub

Roper, L., Hall, M., & Cohn, A. (2021). Overview of the United States' Immunization Program. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 224(12 Suppl. 2), S443–S451. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiab310

Simmons-Duffin, S. (2021). Poll finds public health has a trust problem. NPR.

Stofer, K. A. (2017). Getting Engaged: “Public” Engagement Practices for Researchers: AEC610/WC272, 2/2017. EDIS, 2017(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-wc272-2017

Stofer, K. A., Katsaras, A. V., Dougan, S., & O'Neal, L. (2024). Resources and Strategies to Build Vaccine Confidence among Adults: Adult Vaccination in Florida. EDIS, under review.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Michael Gutter for the idea for this series.