The recent national corn yield contests have shown yield potential of irrigated corn to be 500+ bu/acre with current corn hybrids in the southeastern United States. Factors that can result in less-than-optimum yield for corn include stress caused by too little or too much moisture, lack of fertility at certain growth stages, and nonoptimal heat or light intensity. Each of these factors, along with pest problems, can chip away at the yield potential of the hybrid, with Florida average yields being about 25% of what regional contest winners make.

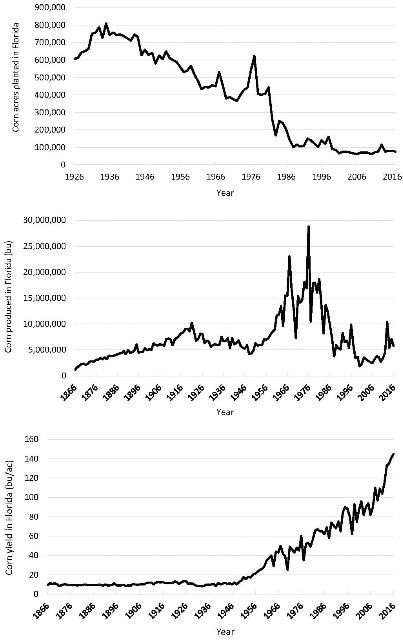

Field corn is important in Florida for both grain and silage. Corn is used widely in the dairy and livestock industries and is risky to grow without irrigation. Florida has regained some of the lost infrastructure for handling, drying, and storage. Corn acreage in Florida was around 400,000 acres in the 1970s (Figure 1). By the late 1980s, acreage had declined to about 100,000 acres. Acreage has averaged around 100,000 acres in recent years. However, yields have increased over that same timeframe from about 45 bu/ac to 120+ bu/ac. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, irrigated acres increased dramatically. High corn prices with the ethanol boom resulted in the installation of many new irrigation wells and pivots for both corn and peanut. High corn demand for ethanol production resulted in an increase in acreage and price across the United States. Corn is still grown profitably in rotation with cotton and peanut, with yield benefits to each of the crops in the rotation. However, irrigation is essential to attain profitable corn yields.

Credit: https://quickstats.nass.usda.gov

Economics

Corn can be produced economically in Florida as a grain or silage crop. Budgets are available at http://www.agecon.uga.edu/extension/budgets/corn/index.html.

Land Preparation

A good soil management program protects the soil from water and wind erosion, provides a weed-free seedbed for planting, disrupts compacted layers that may limit root development, and allows maintenance or an increase of organic matter. Strip-tillage into killed cover crops, winter grazing, or old crop residue helps to meet all of these objectives.

Water erosion is a significant problem on all tilled soil types that have no cover crops during the high-rainfall winter months. Wind erosion can be a problem on sandy Coastal Plain soils in early spring when blowing sand can severely injure young corn plants. Crop residue left on the soil surface or a cover crop effectively reduces water and wind erosion. Using minimum-till planting practices with high-residue cover crops or following winter grazing helps reduce soil loss and "sand blasting" from wind erosion. Conservation tillage is a widely accepted practice in southeastern crops, including corn. Strip-tillage leaves various amounts of crop residue or cover crop on the surface, improving water infiltration and reducing soil erosion.

Strip-tilling into a previous crop residue or cover crop is effective as long as the seedbed is not rutted from the previous harvesting operation or washed out by heavy rains. It is desirable to kill cover crops several weeks ahead of planting to reduce competition from the cover crop and to reduce cutworm and southern corn rootworm damage to young corn seedlings. However, many corn producers have cattle that graze these fields up until the day corn is planted. In this case, planting into live root systems occurs. Therefore, insecticides to protect the young corn seedlings from cutworm and other soil insect damage, or varieties with genetic technology that provides resistance to these pests should be used. Insects are seldom a severe problem if cover crops have been killed 3–4 weeks prior to planting. However, planting corn after winter grazing results in higher nutrient availability to the corn crop in the soil. Recent research shows larger root systems following winter grazing, which can translate into higher yields.

Mulch from killed pasture grass or crop residue conserves moisture. Strip-till corn often yields more than conventional-tilled, non-irrigated corn in years when moisture is limited (Table 1). Effective erosion control needs residue of at least 3,000 pounds per acre. Research has shown that the presence of more residue increases the moderation of soil and plant canopy temperatures and improves the conservation of moisture. Water is usually the main limiting factor to corn yield in Florida unless irrigation is provided.

A compaction layer occurs naturally on Coastal Plain soils. This compacted layer restricts root growth as well as water and nutrient uptake by the plant. It should be disrupted by chisel plowing, or with an in-row subsoiler at planting. In-row subsoiling has increased corn yields over 50% on soils where no or limited irrigation occurs (Tables 2 and 3). Subsoiling enables corn to develop deeper root systems that make better use of subsoil moisture and improves the chances of recovering nutrients as they move through the soil.

Corn generally grows best in deep, well-drained soils, although good yields have been obtained on a wide variety of soil types with irrigation. Land preparation to warm up soils is not necessary for corn, because corn is not as sensitive to cold soils as many other crops.

Hybrid Selection

Growers have one chance to make the right decision regarding the corn hybrid to use each year. Differences among hybrids in yield potential, maturity, standability, disease resistance, grain quality, and adaptability can be obtained from university performance trials. For irrigated or non-irrigated corn production, performance trials conducted in locations closest to the farm should be studied. Growers should use 2–3 of the best hybrids because hybrids do not perform identically under all conditions.

Disease resistance is a necessary component of hybrid selection for the South. Higher humidity, fluctuating water availability, and higher plant populations under irrigation will favor many diseases. Hybrids should have resistance to southern corn leaf blight, anthracnose, gray leaf spot, common rust, southern rust, etc. Corn planted after corn is especially susceptible to leaf diseases because there is a buildup of spores throughout the growing season. Bt corn survives later planting because of insect resistance, but it may fail to produce grain due to little disease resistance. There are several fungicides labeled for corn that should be considered if disease is found soon after tasseling. Grain quality depends on shuck coverage and grain hardness to retain moisture and inhibit insect penetration into the ear.

Corn maturity is classified as early (short-season), medium (mid-season), or late (full-season). In general, the earliest-maturing hybrids best adapted to Florida mature about 115 days after emergence. Maturity will range up to 125 days for full-season hybrids. Early- and medium-maturing hybrids are usually better adapted to irrigated corn production because: they mature 1–2 weeks earlier; are generally shorter and less subject to lodging; may need fewer irrigations; and are more suitable for use in double-cropping than late or full-season hybrids. However, full-season "tropical" hybrids are often grown after early-season corn hybrids for silage. If the farm workload normally prevents harvesting early- to medium-maturing hybrids within 30 days after physiological maturity (black layer), consider planting a later-maturing hybrid, which normally has better shuck coverage.

Results of hybrid evaluation tests for grain and silage are available from the web and county UF/IFAS Extension offices. Hybrid evaluation information is available on the University of Georgia website (http://www.swvt.uga.edu/). Consistent performance across several locations and years usually means better yield stability. It is important, however, to compare hybrids within maturity groups. Growers should test new hybrids on their farms but should not plant an untried hybrid to large acreages.

Primary selection criteria when choosing a hybrid include the following:

- Grain yield

- Maturity

- Stalk strength

- Grain quality and disease and insect resistance

- Silage yield and digestibility

Most hybrids are available with herbicide and insect traits that give value for pest control. These traits include multiple Bt traits for insect resistance and those with resistance to herbicides such as Roundup, Ignite, IMI (imidazolinone), and others. High-oil content corn hybrids are also available for planting in the Southeast. Because they are priced higher than conventional hybrids, these hybrids should be used only where the specific trait is of economic benefit. Late-planted (May–July) corn should have the Bt gene for insect control.

Planting Growth and Development

To produce good irrigated corn yields, timely management and an understanding of how corn grows and develops are necessary. Although growth rates vary among hybrids and growing conditions, Table 4 is a general outline of corn development for a medium-maturity hybrid in Florida.

Planting Date

Corn growth and development are primarily dependent on temperature rather than day length. Successful germination requires a morning soil temperature of 55°F at a 2-inch depth for three consecutive days. This can range from early February in light sandy soils to mid-March on heavy soils. Frost may still occur after these planting dates, but corn normally withstands frost damage to aboveground tissue, because the growing point is still below the soil surface until corn reaches a height of about 12 inches.

In Florida, planting dates for corn begin in late February and proceed to late April. Corn may be planted in late July or early August as a second crop.

Advantages to early planting include:

- More stored soil moisture

- Higher yield potential

- Lower temperatures during pollination

- Longer day lengths at pollination

- Early harvest before cotton and peanuts

- Less insect and disease pressure

When moisture is adequate, plant seed between 1 and 2 inches deep. When soil moisture is deeper than 2.5 inches, waiting for a rain or irrigating may improve stands. In cold sandy soil, the depth may need to be closer to 1–1.5 inches. Germination time and emergence will vary with moisture and temperature from 5 to 30 days.

Table 5 shows irrigated corn yield data from two locations averaged over several hybrids. Irrigated yields tend to be fairly consistent from February through April, and then decline after April due to insect damage and disease. However, tropical hybrids with insect resistance genes can produce high yields into June. Non-irrigated corn may do best during late-April planting if normal rainfall occurs in July and August. Non-irrigated corn is at risk each year because dry periods of three weeks or longer often occur.

Plant Populations and Row Spacing

The optimum plant population varies with soil type, hybrid, irrigation, fertility, and other management practices. Optimal yields are achieved when emergence and plant spacing are uniform—so-called “photocopies and picket fences.” Irrigated corn requires higher plant populations than non-irrigated corn to fully utilize the potential of irrigation. Seeding rates depend on the hybrid, yield expectations, and row width. Recommended plant populations for non-irrigated corn range from 16,000 to 24,000 plants/acre. Seeding rates for irrigated production usually range from 24,000 to 34,000 plants/acre. Seed companies normally provide a recommended population for each hybrid. Generally, 24,000–32,000 plants/acre are recommended for most early- and medium-maturing hybrids with irrigation. Plant populations for the later-maturing hybrids should be 22,000–26,000 plants/acre. Excessive populations increase seed costs and may reduce yield due to inadequate watering or rainfall and lodging. Plant 10%–15% more seed/acre than is necessary to produce the desired plant population. Corn seed generally germinates at the rate of about 95%; another 5%–10% may be lost to insects, disease, or other pests.

At high plant populations, studies reveal that increased yields can be obtained with narrower rows. Greater space between plants allows the plants to exploit moisture, nutrients, and light. It also helps weed control by shading the ground more quickly. Row widths of 30–36 inches are adequate for top-irrigated yields. In some studies, twin row yields have shown to yield 5%–10% higher than single rows; however, water and other factors usually limit yield more than plant population.

To get population/acre, count the number of seeds in one row for the indicated distance (Table 6) and multiply this number by 1,000. Check several rows to be certain each planter unit is working properly. It is always best to double-check the planter to ensure seed drop is providing the desired populations. Vacuum planters have excellent control in attaining desired seed drop and plant populations. Whether old or new, well-maintained planters are necessary for evenly distributed plant populations.

If corn is being produced without irrigation, a yield goal of no more than 125 bushels per acre should be set. Under these conditions, aim for lower plant populations. Choose management practices accordingly. For sandy soils with limited irrigation, use the lower range of the recommended plant population for irrigated corn.

Corn has its highest yield potential in about 15-inch rows. Equipment considerations, however, may limit the use of narrow rows, because adapting some equipment may not be practical. Narrow rows should be one consideration when purchasing new equipment.

Fertilization

A good fertility program should be based on the soil fertility level as determined by soil tests and yield goal. Fertilization programs not based on soil tests may result in excessive and/or suboptimal rates of nutrients being applied. Soil samples should be taken each fall to monitor fertility level and lime requirements.

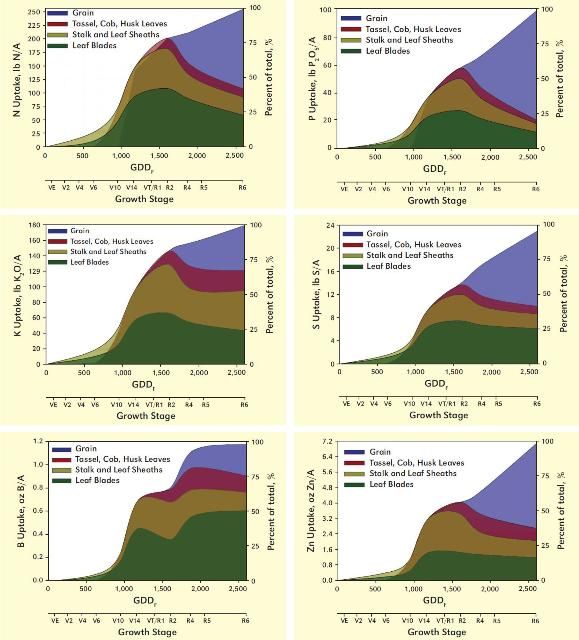

Coastal Plain soils are naturally acidic and infertile. Therefore, substantial quantities of lime and fertilizer are required for optimum yields. Corn cut for silage requires more nutrients than corn grown for grain because cutting silage removes all of the nutrients from the field in the aboveground plant parts. The removal of potassium is especially large in comparison to grain harvest. Table 7 gives a comparison of the nutrients contained in grain and stover. Figure 2 shows nutrient uptake patterns that were determined for high-yielding corn in Illinois.

Credit: Bender, R. R., J. W. Haegele, M. L. Ruffo, and F. E. Below. 2013. "Nutrient Uptake, Partitioning, and Remobilization in Modern, Transgenic Insect-Protected Maize Hybrids." Agronomy Journal 105(1): 161–170; and Bender, R. R., J. W. Haegele, M. L. Ruffo, and F. E. Below. 2013. "Modern Corn Hybrids' Nutrient Uptake Patterns." Better Crops 97(1): 7–10.

Lime

Many fields do not have to be limed for corn if corn is grown in rotation with peanuts, which are normally limed. Fields that have continuous corn or are rotated with other grass crops may become acidic due to: use of high amounts of nitrogen, which is acid forming; leaching of calcium and magnesium; and nutrient removal by high-yielding crops, especially silage. Corn grows well in soil with a pH of 5.6–6.2. Soil with a pH below 5.2 can fix plant nutrients, especially phosphorus, in forms unavailable to plants. Also, because most bacteria cannot live under very acidic conditions, liming increases bacterial activity that breaks down soil organic matter to make soil nitrogen and other nutrients more available to the crop. Likewise, herbicide activity of triazine herbicides is most effective when the soil pH is between 5.8 and 6.5.

Magnesium is seldom a limiting nutrient in corn production if dolomitic limestone is used as the lime source. Corn often shows magnesium deficiency even when soil levels are adequate during the peak period of nitrogen uptake (40–70 days after planting), but symptoms usually disappear after 10–14 days.

Nitrogen

Nitrogen (N) is very mobile in sandy Coastal Plain soils and can be lost if excessive rainfall occurs. To increase the efficiency of N recovery during the season, split applications are recommended to time N application to the needs of the plant. Nitrogen is typically the most limiting nutrient for high yields. A rough rule of thumb is that the crop needs 1.0–1.2 pounds of actual N for each bushel of corn produced. About 20%–25% of the N needs of the crop can be applied at planting as a starter fertilizer near the row. Placing N at-plant two inches below and two inches to the side of the seed (a "2x2 placement") is recommended to limit N losses and maximize uptake. The remaining N can be applied sidedress and/or injected through the center-pivot systems (fertigation). If all the N is applied with ground equipment, apply 35–45 lb/acre at planting and the remainder when corn is 12–15 inches tall on heavy soil. It can be split again on sandy sites when corn is 30–36 inches tall.

In addition, overhead irrigation may enable N application through fertigation even later in the season. No yield increase has been found from N applied after the silk-and-tassel period. If N is to be injected through the irrigation system, apply 30–40 pounds at planting and make a sidedress application of 30–50 pounds per acre when the corn is 12–15 inches tall. The remainder of applications may be made through the irrigation system on a biweekly basis until the total required N is applied in 3–5 applications. This should be completed by tassel emergence. A typical N uptake curve shows that corn takes up about 15 lb/acre by the time corn is about 15 inches tall (see Figure 2). It starts a rapid uptake period at this time. It will grow about 3 feet the next two weeks with good moisture and take up about 80 lb/acre of N during those two weeks, followed by another 50 lb/acre uptake in the next two weeks prior to tassel emergence. Therefore, at least 130 lb/acre of N will need to be available in the four weeks after corn reaches the 15-inch height range. Over the next 6 weeks of ear formation, corn will take up another 100–150 lb/acre of N. However, if N is adequate until tassel emergence, no yield increase would be expected from additional application after tassel emergence. Only grain N content is increased with N applied after tassel emergence. When N is applied and a rain of over 2 inches occurs in a short period, reapply an additional 30 lb of N/acre to compensate for what ran off or was leached out of the root zone.

Phosphorus and Potassium

Phosphorus and potassium should be applied according to a soil test. A 230-bushel crop can take up to 45 pounds of phosphorus and 180–240 pounds of potassium depending on soil P and K levels. Corn may exhibit phosphorus deficiency symptoms (stunted plants and purpling of leaves) on cool, wet soils, particularly early in the season when soil temperatures are low, even when soil test P levels are high. This is because fungi associated with P uptake are inactive in cold weather and cannot assist the corn with P uptake. Generally, all the phosphate and, on most soils, all of the potash are applied at or before planting. Some or all of the phosphorus requirements may be obtained through the use of starter fertilizer. On deep sands, apply potash in split applications: 1/3 at planting, and the remainder when corn is about 15 inches tall. Many corn hybrids respond favorably to a mixture of half 28-0-0-5 and 10-34-0 as a starter fertilizer.

Secondary and Micronutrients

Corn requires about 20–30 pounds of sulfur per acre. On deep sands, apply sulfur in split applications with N. All sulfur should be applied in the sulfate form. Nitrogen sources with sulfur are usually sufficient to meet plant requirements.

Zinc and manganese deficiency can be prevented by using 2–3 lb/acre of the element material if called for by soil tests. Do not use zinc unless soil test levels are low, because peanuts (if used in rotation) are very sensitive to high levels and can develop zinc toxicity and split stems. If needed, apply preplant or at planting in starter fertilizer as chelates, preferably as a liquid formulation.

Boron deficiencies can occur on sandy soil low in organic matter. Generally, use one pound per acre of boron applied in split applications. It is best to apply boron with the nitrogen applications and as a liquid formulation.

Fertilizer Placement

The main objective in fertilizer placement is to avoid injury to the young seedling and to get proper placement for most efficient root uptake. Band placement of N near the row at planting and on corn up to about 15 inches tall has been shown to be most efficient because the root system is limited. Broadcasting potassium fertilizer is less expensive for labor and just as efficient as banding on soils with medium fertility. However, our research has shown that 25% less P and K may be used if applied in band vs. broadcast applications, while yields are often higher. Generally, all of the phosphorus is applied as a starter and all of the potassium is broadcast preplant or in pre- and post-plant applications.

Starter Fertilizer

Small amounts of N, phosphorus, sulfur, and micronutrients are often used as a starter fertilizer. The main advantage of starter fertilizer is better early-season growth, earlier dry down, and with many hybrids, higher yield. Corn planted in February, March, or early April is exposed to cool soil temperatures, which may reduce phosphate uptake. Banding a starter fertilizer two inches to the side and two inches below the seed increases the chances of roots penetrating the fertilizer band and taking up needed nitrogen and phosphorus. Starter fertilizer can also be used in a surface dribble for strip-till planting with the solution applied 2 inches to the side of the seed furrow for each 20 lb of nitrogen used.

Currently, the most popular starter fertilizer is ammonium polyphosphate (10-34-0), a liquid. Monoammonium and diammonium phosphates are dry sources that are equally effective. There is generally no advantage in using a complete fertilizer (NPK) as a starter because applying N and phosphorus is the key to early growth. If soil test levels for P and K are high, a starter with 30–40 lb/acre of N and 15 lb/acre of P is adequate for starter application. Normally, 10–15 gallons of a starter fertilizer containing one-third to one-half 10-34-0 and the remainder as 28-0-0-5 have been effective for early corn growth. Corn will take up around 15–20 lb/acre of N and 5 lb/acre of P by the time the corn is 15 inches tall. Therefore, high rates of starter P are not necessary unless it is used to supply all of the P for the corn crop in a low-soil test field.

Plant Analysis

Soil tests serve as a sound basis for determining fertilizer requirements for corn. However, many factors such as nutrient availability, leaching, and crop management practices may require modification in a basic soil fertility program to maximize fertilizer use efficiency and crop yield during the season. Plant analysis can be used to monitor the nutrient status of the plant, to confirm a suspected nutrient deficiency, and to aid in the adjustment of the fertilizer program in subsequent years.

Fertility in Conservation Tillage

Because lime and P cannot be incorporated and do not move quickly through the soil profile, they must be managed carefully under conservation tillage. Adding small amounts of lime and removal rates of P every year will help to keep pH and P levels adequate. Under conservation tillage, having the soil tested and applying needed lime and P are most critical before a cover crop is planted. All the needed P can be applied for both a cover crop and the corn crop at the same time. However, some corn hybrids will respond to starter N and phosphorus even at adequate soil test P levels. On heavier soils, all the potassium necessary for a cover crop and corn crop can be applied at the same time. On lighter, sandier soils, the potash application should be split, with one-third applied in the fall for the cover crop and the remainder split between corn planting time and topdressing. When a small grain cover is planted in the fall, apply only 20–30 pounds of N before fall planting. If grass shows N deficiency in December or January, apply another 20–30 pounds. A starter fertilizer can be applied at planting to corn. The same basic fertility program can be used on conservation till-planted corn as with conventional tillage as noted above.

Irrigation

Research in the Southeast has shown that irrigation significantly increases corn yields, although the increase may vary from year to year, depending on weather and other factors. Irrigation, when combined with other good production practices, should result in yields that are consistently 150–240 bushels per acre and higher with good management. Non-irrigated corn yield can range from 5% to 75% of irrigated corn (Table 8). It has been said that you pay for irrigation whether you have it or not.

Total water needs for a corn crop vary from 20 to 24 inches during a season, depending on weather, plant density, fertility, days to maturity, and soil type. With normal rainfall events, about 12 inches of irrigation are often needed. Research has shown that it takes about 5,000 gallons of water to produce one bushel of corn grain. Ample moisture should be available in the root zone until physiological maturity (black layer, or maximum dry weight of grain) is reached, which is about 60 days after tassel emergence.

Adequate drainage is necessary in depressions or low spots in fields to allow runoff water to be routed off the field in 24 hours or fewer. A coarse-textured soil will need to be irrigated more frequently than a fine-textured soil. Also, in general, fine-textured (clay and silt loam) soils have a lower infiltration rate than coarse-textured (sandy and sandy loam) soils. Typical Coastal Plain soils will hold about 0.7 to about 1.6 inches of water per foot. The key is to irrigate to avoid runoff or plant stress.

Corn is more responsive to irrigation than many crops. The water requirement of corn is most critical from tasseling through ear fill, needing as much as 0.33 inches per day. Moisture stress prior to tasseling can cause a yield reduction of 10%–40%; moisture stress between tasseling and soft dough stages may result in a 20%–50% yield loss; and moisture stress from the soft dough stage to maturity can cause a yield reduction of 10%–35%. A rough rule of thumb is that corn requires about 1 inch of water every 7–10 days until it reaches a height of 15 inches, then an inch every 5–7 days until tassel emergence, and finally an inch every 3 days from tassel emergence until physiological maturity. Corn takes up little water if it is cloudy. Moisture probes will verify when water is required.

Disease Management

Each year, corn yields are reduced in the Southeast due to diseases. Diseases also lower the value and quality of the grain and may increase harvesting costs due to lodging. Generally, warm, wet weather favors leaf, ear, and stalk diseases. Seedling diseases are usually worse during cool, wet weather following planting. Several diseases that can impact corn production are discussed below.

Seedling Diseases

Root and Stalk Rots

Caused by several different fungi, these diseases can result in corn lodging and inferior ears from lodged plants on the ground and premature ripening on diseased stalks. Stalk rots typically result in greater damage in poorly drained soils, and in slow drying conditions due to poor air movement. Control practices include using good cultural practices, planting recommended varieties with resistance to lodging, using early-maturing varieties where lodging is severe, and avoiding poorly drained fields. Diseases that fall into this category include Pythium, Fusarium stalk rot, and charcoal rot. Suspected diseases can be diagnosed by sending samples to UF/IFAS pathology labs using the submission process described in Sample Submission Guide for Plant Diagnostic Clinics of the Florida Plant Diagnostic Network (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/sr007).

The soilborne fungus Fusarium stalk rot normally begins soon after pollination and becomes more severe as plants mature. Symptoms include whitish-pink discoloration of the pith, stalk breakage, and premature ripening.

Charcoal rot (caused by the fungus Macrophomina) can result in severe yield losses if hot, dry environmental conditions coincide with post-flowering growth stages. Symptoms usually start showing up on plants approaching maturity, appearing as brown water-soaked lesions on the roots that later turn black. The fungus moves into the plant's lower nodes, causing premature ripening and lodging. Numerous black sclerotia inside the stalk give the appearance of powdered charcoal. This disease can be dramatically reduced by irrigating before flowering begins. Additionally, a balanced fertility program can have a positive impact because high nitrogen rates and low potassium rates increase charcoal rot severity. Resistant varieties are not available, but planting varieties that possess high stalk strength helps reduce lodging.

Foliar Diseases

Leaf Blights or Leaf Spot

Caused by different species of the fungus Helminthosporium, these diseases favor wet or humid field conditions. Symptoms are lesions that are tan and oval to circular, usually with concentric zones. The fungus also attacks ears, causing a black, felty mold over kernels. Race two of southern corn leaf blight produces oblong, chocolate-colored spots up to 1 inch in length. Tolerance can vary among corn varieties. Control practices include planting of recommended, resistant varieties and use of fungicides.

Ear and Kernel Rots

Some of the fungi that cause silk rots or leaf blights may also infect the ear, with symptoms including a pink, powdery mold growing over the surface of rotted grains (Fusarium) and dense, white mold growing between the rows of rotted kernels (Diplodia). Some protection can be obtained by planting varieties resistant to ear-feeding insects and lodging. Some hybrids may offer slight resistance. Early harvest and proper storage are helpful.

Maize Dwarf Mosaic

First appearing on the youngest leaves as an irregular, light- and dark-green mottle that may develop into narrow streaks along veins, this disease is common in the Southeast. As plants mature, leaves become yellowish-green. Plants are sometimes stunted with excessive tillering, multiple ear shoots, and poor seed set. Early infection, vectored by several species of aphids, may predispose plants to root and stalk rots. Some hybrids have resistance to virus diseases.

Smut

This fungal disease is common and generally results in losses from 1% to 10%, although resistant varieties can cut losses significantly. All aboveground parts of the plant are susceptible, but the tender ears are most commonly attacked. Symptoms include ¼- to ½-inch galls with a shiny greenish to silvery-white color. The interior of these galls darkens and turns into masses of powdery, dark brown-to-black spores. Affected plants may appear reddish near maturity. Again, control is usually obtained by avoiding susceptible varieties, mechanical injury during plowing, and excessive nitrogen.

Rusts

Common rust is generally found on plants relatively early in the season (before tasseling). It survives the winter on green corn or on wood sorrel and grows best in the cooler temperatures that are common early in the season. Southern rust does not overwinter but is thought to come in annually on wind currents from Latin America. It is favored by hot, humid temperatures that occur later in the season. Both are characterized by the formation of pustules (small, raised blisters that contain rust-colored spores of the fungus) on leaves. Symptoms of both rusts may overlap. Common rust pustules are oval to elongate, often ¼ inch long on leaves other than the lowest ones, and dark cinnamon brown. Southern rust pustules are circular, 1/8–1/6 inch in diameter, and tan-orange-brown in color.

Although it is rare in Florida, common rust will kill or severely damage corn plants, while southern rust can be devastating under favorable environmental conditions. Most commercial hybrids have some degree of resistance to common rust. There is little resistance to southern rust presently available. Currently, early planting and use of fungicides are the primary defense. Rust is the most serious disease to corn planted in June and July. It often kills plants and can cause rapid dry down of corn planted late for silage.

Nematode Management

Several nematode species are known to damage field corn in Florida. Most important is the sting nematode (Belonolaimus longicaudatus), whose distribution is limited to very sandy soils such as those typical of peninsular Florida. Stubby root (Paratrichodorus spp.), lesion (Pratylenchus spp.), lance (Hoplolaimus spp.), and root-knot (Meloidogyne spp.) nematodes may also affect field corn growth. Yield reductions by most kinds of nematodes parasitizing field corn are usually most severe in the sandiest soils and during times of drought. Generally, well-irrigated field corn can tolerate considerable numbers of nematodes.

Symptoms

Aboveground symptoms of nematode injury include stunting, thin stands, premature wilting under moderate heat or drought stress, uneven vegetative growth, and nutrient deficiency symptoms. Because nematode numbers can vary greatly within short distances in the field, areas of stunted growth, yield reduction, and other aboveground symptoms of nematode damage vary greatly in shape, size, and distribution. Symptoms and yield loss are worse in soils that are sandy, dry, and infertile. Roots injured by nematodes are usually stunted, often with few fine secondary feeder roots. Root tips may be blunt and swollen. Occasionally, tufts of many stunted lateral roots emerge near the main root tips. By damaging root tips as soon as they emerge, nematodes can be especially injurious to young seedlings. Even under moderate stress, nematode-damaged roots may cause young plants to die, resulting in a thin crop stand.

Diagnosis

Nematode problems in field corn can be determined only by nematode assay. Prior to taking samples, contact your county UF/IFAS Extension agent for information about available sampling tools, shipment bags, and proper procedures for submitting samples. Samples should not be taken when the soil is dusty and dry or soggy and wet. Two sampling strategies may be employed. A general survey should be performed every three to four years, and soil samples should be taken soon after field corn has been harvested. A soil core (1 inch wide by 8–10 inches deep) should be taken for every 2–3 acres in a 20-acre block containing a uniform soil type and cropping history. The cores should be thoroughly mixed and a 1-pint sample placed in a sealed plastic bag and kept cool (not frozen) before immediate shipment to a laboratory. For a more definitive strategy where a nematode problem is suspected, several soil cores from within and immediately around a poor growth site should be taken while the crop is still growing. Include portions of damaged roots with the soil sample. These samples should be processed as described above. More information on submitting nematode samples can be found at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/sr011.

Management

The worst nematode problems occur in fields where field corn and/or close relatives such as sorghum have been grown every year along with other grass crops during the winter. Rotation to unrelated crops in successive years is usually better for all crops in the planting cycle, not just the cash crops for which crop rotation plans are primarily designed. Of all the agronomic crops commonly grown in rotation with field corn in Florida, peanut and cotton are probably the best for reducing nematode pests of field corn. Several nematicides have been approved for management of nematodes of field corn (see Ask IFAS publication ENY-001, “Management of Plant-Parasitic Nematodes in Florida Field Corn Production” [https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ng014]). Use of nematicides generally results in higher corn yields on sandy Coastal Plain soils.

Weed Control

Weed management can be enhanced with production practices such as crop rotation, timely planting, soil fertility management, and cultivation. Many growers use strip-tillage when planting corn after winter grazing and do not cultivate but rely entirely on herbicides for weed control.

Johnsongrass can be hard to control in cornfields on heavy soils. It may be necessary to control these weeds in a preceding year’s planting of peanut or cotton, or to use herbicide-tolerant hybrids that allow over-the-top applications of grass herbicide materials.

Herbicides are needed to control weeds that are not controlled by the other practices. Rates may depend on soil texture, organic content, and targeted weed species. Always read and follow label directions and precautions when using herbicides. Rates are per acre and may be given in a range from coarse-textured to fine-textured soils. For weed control recommendations, refer to Ask IFAS publication SS-AGR-02, “Weed Management in Corn” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/wg007).

Insect Control

The economic threat that insects pose to corn will vary from year to year. Any one of several insect species can cause yield losses, either by direct feeding or vectoring a plant virus such as maize dwarf mosaic. Control requires knowledge of insects and available management options. Effective insecticides are available for many insects that threaten corn. Always read and follow label directions and precautions when using insecticides. Because insect infestations are typically highest in late summer, early-planted corn is likely to have fewer problems. Fall armyworm damage is usually light until July and August. First-generation southwestern corn borer is lighter than second and third generations, and corn earworm damage is usually lighter in early-planted corn. Many insects are controlled by insect traits of corn varieties. Check with your seed supplier for resistance against common pests on your farm.

Soil Insects

Several soil insects attack corn by feeding on germinating seed, roots, or underground stems. If fields have a history of soil insect problems, an application of a soil insecticide may be justified. Several of the most important soil insects are discussed below.

Seed Corn Maggot

This is a small, white maggot that feeds on corn seed, which can cause stand reduction or loss. The feeding may cause seed to fail to germinate or result in weakened seedlings that may die. Any condition that delays seed germination may increase damage from seed corn maggot, with greatest damage in cool, wet springs. Damage can be detected by digging in areas where plants have failed to emerge. Serious damage may require replanting. Systemic in-furrow insecticides aid in preventing infestations of seed corn maggots. Banded treatments should be incorporated lightly.

Southern Corn Rootworm

This pest, the larva of the spotted cucumber beetle, damages corn when larvae feed on root systems. The feeding causes roots to be stubby, and tunneling is obvious where larvae have fed. Severe injury may cause plants to lodge, and a goosenecked appearance develops as plants try to grow erect. Soil insecticides can control corn rootworms. Apply as directed either in-furrow or in a band 7 inches in front of the press wheel and incorporate lightly at planting.

Wireworms

Wireworms feed on germinating seeds and the root system. Larvae are yellowish-brown to brown and wire-like in appearance. Infestations appear heaviest in areas following sod.

Lesser Cornstalk Borers

This insect damages the plant by boring into the stalk. This boring causes dead-heart and may greatly reduce the stand. It tends to be a bigger problem on sandier soils. Lesser cornstalk borer problems generally are reduced in conservation tillage, especially if planting into actively growing crop residue or weeds.

White Grubs

Another root-system feeder, this grub causes plants to be stunted and reduces stands. Lodging and yield reductions may also result.

Cutworm

Several species of cutworms attack corn and cause similar plant injury, cutting plants down at the soil line. Damage can often be prevented by early seedbed preparation or early killing of the cover crop to allow natural control of worms. Applying an insecticide to the row when damage is first noticed may be necessary. Insecticides should be applied at labeled rates when stands are threatened. Sprays should be directed to lower portions of plants and to soil around the base of plants. In reduced-tillage corn, the use of a soil-applied insecticide also helps suppress cutworm populations.

Sugarcane Beetles

This pest, which may be called rough-headed corn stalk-beetle, is black and about ½ inch long. It burrows into the ground and feeds on the corn stem about ½–1 inch below the soil surface, making a ragged hole in the stem. It tends to be most prevalent in low, wet spots in a field. Control is difficult.

Chinch Bugs

Chinch bugs can be an occasional problem in corn, but when they reach threshold levels, they can be a serious problem. Chinch bugs are 1/6–1/5 inch long and have black wings with white covers crossed with a zigzag line. They are normally found near or below the soil line and behind leaf sheaths. Systemic in-furrow insecticides can provide control.

Foliar Insects

Corn Flea Beetles

Corn flea beetles may kill seedling corn by eating holes in leaves and severely weakening the plant. The pest hops like a flea and is small, black, and about 1/6 inch long. Treatments should be made when beetles are abundant and affecting stand vigor.

Fall Armyworm and Corn Earworms

Damage to corn whorl or buds may be caused by the corn earworm and fall armyworm. The corn earworm occasionally infests the whorl but is more likely to cause damage to developing ears. Bt corn has resistance to these worms and may be a better choice for late plantings for silage. However, Bt corn has little disease resistance, and yields may be severely reduced by late planting.

Stink Bugs

Generally, the southern green stink bugs are observed feeding on corn. Research has shown that the stink bugs must feed when the developing ears are ½–¾ inch long or shorter for significant damage to occur. The ears enter the susceptible period about two weeks before silking. Stink bugs pierce the plant with their beaks and inject saliva while simultaneously sucking out sap. When the ears are small, this feeding can result in the loss of the entire ear. When stink bugs are seen feeding on older ears, which may be seriously malformed, the damage is actually the result of earlier feeding. Fields should be checked for stink bugs before the ear shoots have fully emerged. Scout for stink bugs by making counts in several areas of a field, but pay careful attention to field margins because this is where they normally infest first. Treat for stink bugs when 5% of the plants are infested. There are currently no genetic traits in corn for controlling stink bugs. In some years, stink bugs can also be an early-season problem. Growth and development of young corn plants can be affected by stink bug feeding. Treat corn under 2 feet tall when 10% of the plants have one or more stink bugs.

Harvesting and Drying

Ideally, corn should be harvested between 15% and 18% moisture. Drying costs or high moisture discounts can cause some farmers to wait too long to harvest corn. For large corn acreage, harvesting should start at 25% moisture. Delaying harvest after corn reaches 25% moisture will cause a loss of 1/3 bushel per day per 100 bushels of yield. Corn that reaches 25% moisture in August will take 8–10 days to dry to a moisture of 19%–20%. Thus, delaying harvest for 10 days during this period causes losses of 4–5 bushels per acre. However, corn harvested at 25% moisture requires twice as much moisture to be removed as when harvested at 20%. There is generally a premium paid for grain delivered early, which can help offset drying cost along with the higher yields. Preharvest and harvesting losses may vary due to insect damage, lodging, and ear drop. Corn that remains in the field too long suffers weight shrinkage, damage, and yield loss.

A well-adjusted combine equipped for corn is the first step toward a productive corn harvest. Rasp bars or rotors should be set to properly shell the corn from the cob without cracking kernels. Row spacing should match the corn header. Studies have shown that gathering losses can increase 2.5 bushels per acre if the gathering opening is 4 or 5 inches off the row.

Operate the corn header low enough that the gathering chains enter the row below the lowest ears. Lodged stalks may mean reducing the height so gathering points follow the ground contour. Slowing forward speed recovers more ears that drop easily from lodged stalks.

Corn often has high levels of aflatoxin when grown under stress conditions (moisture stress, temperature, insects, etc.). Early harvest and drying to 15% moisture within 24 hours after harvest will help reduce aflatoxin formation. Corn should be dried to 13% moisture or less if it is to be stored for several months to help prevent spoilage.

Table 1. Influence of soil preparation on yield of corn (bu/acre).

Table 2. Influence of tillage and water management on corn yield (bu/acre).

Table 3. Influence of tillage on corn yields (bu/acre).

Table 4. Outline of corn development for a medium-maturity hybrid in Florida.

Table 5. Influence of planting date on corn yield (Florida and Georgia).

Table 6. Length of row required for 1/1,000 acre at various row widths.

Table 7. Pounds of nutrients removed by the grain and stover of a 180-bu/acre corn crop.

Table 8. Irrigated corn vs. non-irrigated corn production in two different soil types (Georgia).