Cotton (Gossypium spp.) is a major cash crop in the southeastern United States (U.S.). Among the three major essential macronutrients, nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K), N is the most limiting macronutrient and is required in relatively large quantities in cotton production (Khan et al. 2017). N is a critical element influencing cotton growth, yield, and fiber quality. Therefore, N fertilization sufficiency and balance are major concerns for cotton growers (Hickey et al. 2024). Effective in-season N management is essential to maximize crop performance and minimize environmental impacts. One of the most popular methods for monitoring in-season N status is cotton petiole (the stalk that attaches the leaf blade to the main stem) nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N) analysis (Bronson et al. 2021). This method involves the analysis of NO3-N concentration in the petiole during early crop growth stages through full flowering, which ultimately helps to manage N fertilization rates. This publication aims to guide cotton producers, Extension agents, crop advisors, and consultants on the correct method of petiole sampling for NO3-N analysis and interpretation of petiole NO3-N test results, and also discusses ways in which monitoring petiole NO3-N concentration can be used as a tool for effective in-season N management in cotton.

Nitrogen in Cotton Production

Nitrogen is a critical nutrient for cotton growth and development. It is a primary component of chlorophyll (the molecule responsible for photosynthesis) and is crucial for various vital biomolecules such as amino acids, DNA, and proteins, which are essential for plant growth. Even though the N content in cotton lint is minimal, N is necessary to ensure healthy plant growth, boll development, and fiber quality (Hickey et al. 2024). Research shows that precise N management can optimize cotton yield and quality (Shah et al. 2022). On average, it requires 0.1 lb N to produce 1 lb lint (Hickey et al. 2024). Insufficient N can lead to reduced height, leaf yellowing, poor fruiting, and increased boll shed. Conversely, excess N increases susceptibility to insect pests and diseases, can delay reproductive partitioning, and can cause vegetative growth (leaves and stems) at the expense of boll development, ultimately reducing yields and fiber quality (Snider et al. 2021).

Nitrogen fertilizer may be lost through several processes, including denitrification (conversion of nitrate [NO3-] into gaseous N2), volatilization (loss of N2 as ammonia [NH3] from the soil surface), and erosion through runoff and leaching (NO3- and NH4+are highly soluble in water) (Singh et al. 2023a; Duncan and Raper 2019). Moreover, N deficiency may occur later in the season due to increased N demand during the boll-filling stage (Hickey et al. 2024). Therefore, proper monitoring of in-season N requirements and management is essential to achieve the maximum lint yield and high-quality fiber.

Petiole Sampling for Testing Cotton N Status

Petiole sampling involves collecting petioles from cotton plants at successive growth stages and analyzing them for NO3-N content. Analyzing NO3-N levels in petioles is considered to be a reliable indicator of the N status of cotton during the growing season (Bronson et al. 2021). While traditional soil testing provides an initial estimate of N levels in the soil, helping to develop preplant fertilization strategies, it does not account for changes in soil N throughout the season. Also, in Florida and many other southeastern states, farmers do not routinely test for soil N content before planting, which results in either overfertilization or N deficiency during critical growth stages. Petiole nitrate concentration estimates recent NO3-N uptake and availability in plants. Because petiole nitrate levels respond quickly to changes in soil nitrogen availability, they reflect the current N status in the soil solution more accurately (Qiu et al. 2014; Schreiner et al. 2017). This information is essential for deciding whether additional N fertilizer should be applied to optimize production (Gerik et al. 1998).

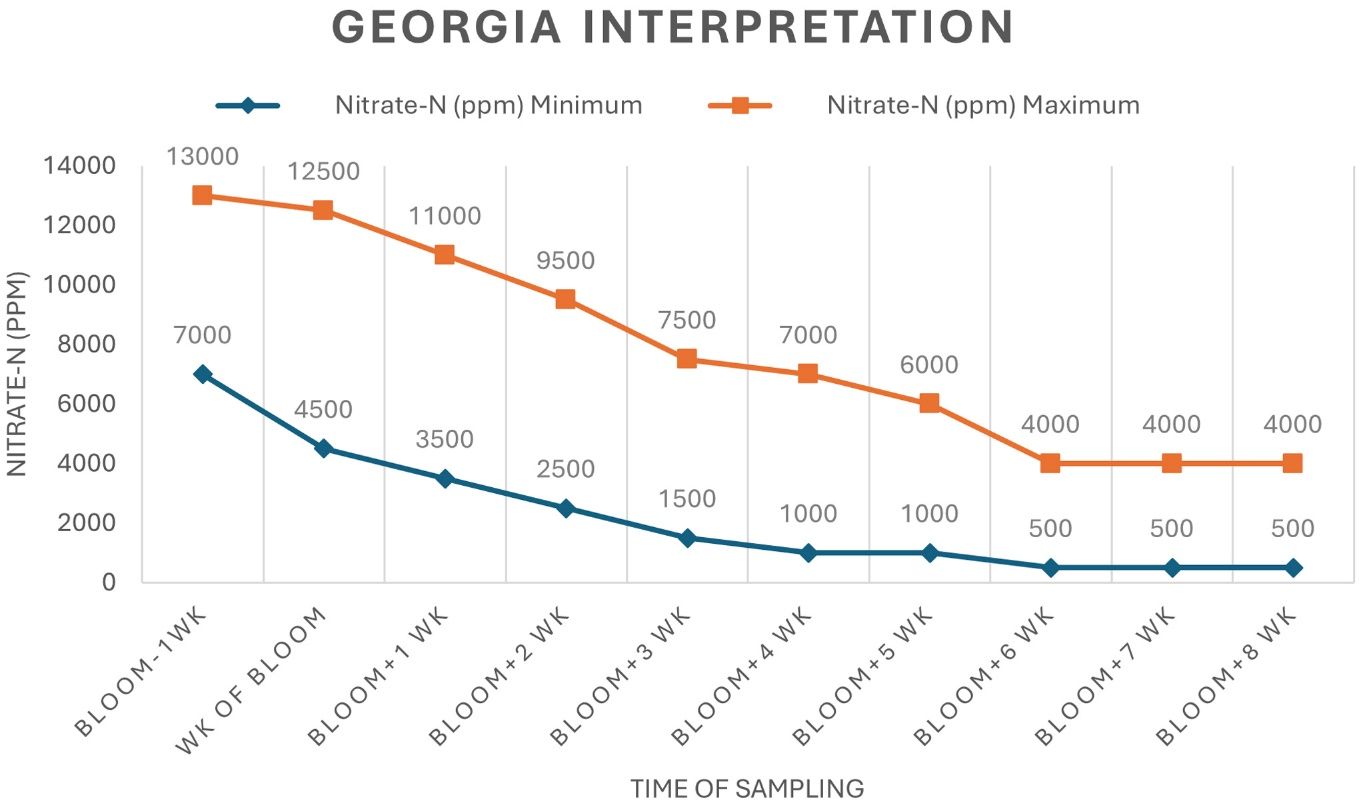

It is recommended to begin petiole sampling one week before the expected first bloom and continue weekly until full bloom or typically around nine weeks after the first bloom (Hickey et al. 2024), thereby monitoring the crop when additional N applications will have the greatest impact. The N demand of cotton decreases after the peak bloom. The petiole NO3-N stabilizes around five weeks after bloom (Figure 2) and no longer provides useful information for guiding N management decisions. In general, there is no need for additional N applications at this stage, since most the N required for optimal yield should be applied before the third week of bloom. Therefore, petiole sampling is practical and beneficial only up to 5 weeks after bloom. Under normal conditions, petiole analysis can often indicate additional N requirements about seven to 10 days before N stress symptoms are observable (Parvej et al. 2021).

How to Collect Petiole Samples

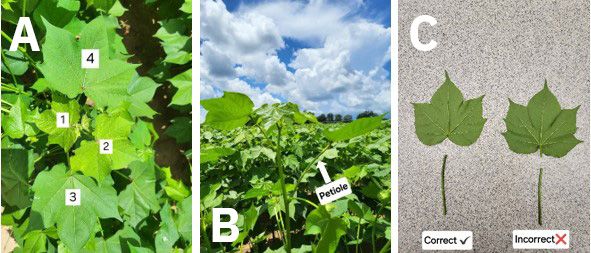

- Select the most recently matured, fully expanded leaf on the main stem, or generally the fourth leaf from the top of the plant. (Do not count the small leaves on fruiting spurs at the terminal end.) If unsure, choose a slightly older leaf rather than a younger one. However, avoid leaves directly supporting the bolls (if present), as these are important to supply nutrients to the developing boll tissue (Figure 1A and Figure 1B).

- Detach the leaf from the plant and immediately separate the full petiole from the leaf blade (Figure 1C).

- Collect approximately 20–25 petioles and leaf blades per sample.

- Place the samples in a plant sample bag to prevent moisture accumulation (avoid plastic bags). You can find information on obtaining plant sample bags from the laboratory website.

- Label the bag clearly with the sample ID and sampling date.

- Store the samples in a cool, dry place and transport/mail them to the appropriate laboratory for analysis as soon as possible. (Note: Overnight shipping is not necessary).

- For first-week and fifth-week samples, place the petioles in an envelope and the leaf blades in a plant sample bag. Insert the envelope into the plant sample bag and ship them together. It is advisable to test NO3-N concentration for petioles and leaf blade samples for the first and fifth weeks because it gives the estimate of recent nitrate uptake from the soil and overall nitrogen accumulated in the leaf, respectively.

- For the remaining weeks (second, third, and fourth weeks), send only the petiole samples, placing them in a properly labeled plant sample bag for each week.

Credit: Akash Shah, UF/IFAS

How to Interpret Petiole Nitrate Test Results

The laboratory report provides NO3-N concentration in parts per million (ppm). However, some labs may simply report results as NO3- concentration. If the report shows NO3-, multiply the value by 0.226 to convert it into the more commonly used NO3-N standard (Brust 2008). These petiole NO3-N concentrations should be compared to standard sufficiency ranges to guide fertilization decisions. Two different interpretations of the sufficiency range are commonly used. The “Arkansas interpretation” is used in the central region of the U.S., except in the arid parts of Texas, Oklahoma, and the western cotton-growing regions (Maples et al. 1977; Sabbe et al. 1972). Cotton farmers across the southeastern U.S. coastal plain soils from Alabama and Florida up to Virginia should use the “Georgia interpretation” (Lutrick et al. 1986; Mitchell and Baker 1997) (Figure 2).

Credit: Akash Shah, Hardeep Singh, Lakesh Sharma, Ethan Carter, and Guilherme Morata, UF/IFAS

The sufficiency range for petiole NO3-N concentration during the different blooming stages represents the desirable range, not a critical threshold. If soil N is sufficient, NO3-N levels in cotton petioles are relatively greater during the squaring stage. As the plant transitions to boll development and filling, petiole NO3-N gradually decreases, as more of the plant N is translocated from vegetative parts to reproductive parts and additional N uptake from the soil declines. Environmental factors, such as moisture, drought, and pest damage, along with management practices, prior fertilizer history, rainfall, and irrigation rates should be taken into consideration while interpreting petiole NO3-N levels because these can all influence analysis results (Hickey et al. 2024). A crop advisor can help farmers interpret the results each week and use this to more efficiently manage N application recommendations.

If Petiole NO3-N Concentration Is outside the Sufficiency Range

When petiole NO3-N levels fall below the sufficiency range, this indicates possible N deficiency; in this case, plants may benefit from an additional N application. Conversely, if the NO3-N concentration is excessive, vegetative growth will also be excessive. This can negatively affect boll development, in part, by increasing shading and poor air circulation. In this situation, do not apply more N; instead, consider applying a plant growth regulator such as mepiquat chloride (commonly known by trade name “Pix”), as per label recommendations (Singh et al. 2023b). (Note: Refer to Ask IFAS publication SS-AGR-475, “Plant Growth Regulators as a Management Tool in Cotton Production,” for recommendations and more information.)

Consider also monitoring petiole phosphorus (P) levels, especially during blooming, as this can provide additional insight into stress factors affecting NO3-N levels. For example, in the first week of bloom, if the NO3-N concentration is between 10,000 ppm and 35,000 ppm and the P concentration is above 800 ppm (0.08%), the plants have sufficient N to support healthy growth and development. However, if the P concentration drops by more than 300 ppm from one week to the next, it may signal plant stress, possibly due to water deficiency. In such cases, it is prudent to wait for the next test results before adjusting N fertilizer applications and to ensure plants are free from any stress (Parvej et al. 2021).

Best Practices for Petiole Sampling

- If possible, take the samples on the same day every week.

- Avoid sampling immediately after irrigation or rainfall events.

- Collect samples from the same field areas each week to maintain consistency over time.

- Quickly deliver (in-person or by mail) the samples to the laboratory to ensure accurate results.

- Use the same laboratory for analysis throughout a growing season to maintain continuity.

- Keep detailed records of petiole NO3-N levels, N applications (rate and timing), and crop performance over several seasons. Reflecting on your annual data and results can help identify trends and improve N management strategies. (Note: A free, downloadable Excel sheet for keeping proper N management records is available.)

References

Bronson, K. F., E. R. Norton, and J. C. Silvertooth. 2021. “Revising Petiole Nitrate Sufficiency/Deficiency Guidelines for Irrigated Cotton in the Desert Southwest.” Soil Science Society of America Journal 85(3): 893–902. https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20213

Brust, G. E. 2008. “Using Nitrate-N Petiole Sap-Testing for Better Nitrogen Management in Vegetable Crops.” Univ. Maryland Ext. Publ.

Duncan, L., and T. Raper. 2019. “Cotton Nitrogen Management in Tennessee.” Publication W 783. University of Tennessee Extension. https://utia.tennessee.edu/publications/wp-content/uploads/sites/269/2023/10/W783.pdf

Gerik, T. J., D. M. Oosterhuis, and H. Allen Torbert. 1998. “Managing Cotton Nitrogen Supply.” Advances in Agronomy 64: 115–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2113(08)60503-9

Hickey, M. G., C. Stichler, and S. D. Livingston. 2024. “Using Petiole Analysis for Nitrogen Management in Cotton.” https://colorado.agrilife.org/files/2011/08/usingpetioleanalysisnitrogenmanagementcotton_25.pdf

Khan, A., D. K. Y. Tan, F. Munsif, M. Z. Afridi, F. Shah, F. Wei, S. Fahad, and R. Zhou. 2017. “Nitrogen Nutrition in Cotton and Control Strategies for Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A Review.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 24: 23471–23487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-0131-y

Lutrick, M. C., H. A. Peacock, and J. A. Cornell. 1986. “Nitrate Monitoring for Cotton Lint Production on a Typic Paleudult.” Agronomy Journal 78(6): 1041–1046. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj1986.00021962007800060021x

Maples, R., J. G. Keogh, and W. E. Sabbe. 1977. “Nitrate Monitoring for Cotton Production in Loring-Calloway Silt Loam.” Univ. of Arkansas Agric. Exp. Stn. Bull. 825.

Mitchell, C. C., and W. H. Baker. 1997. “Plant Nutrient Sufficiency Levels and Critical Values for Cotton in the Southeastern US.” In 1997 Proceedings Beltwide Cotton Conferences, New Orleans, LA, USA, January 6–10, 1997. 606–609. https://eurekamag.com/research/003/232/003232793.php

Parvej, R., B. Tubana, and S. Dodla. 2021. “Guidelines for In-Season Nitrogen Management in Louisiana Cotton.” LSU AgCenter. https://www.lsuagcenter.com/articles/page1626546706705

Qiu, W., Z. Wang, C. Huang, B. Chen, and R. Yang. 2014. “Nitrate Accumulation in Leafy Vegetables and Its Relationship with Water.” Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 14(4): 761–768. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-95162014005000061

Sabbe, W. E., J. L. Keogh, R. Maples, and L. H. Hileman. 1972. “Nutrient Analysis of Arkansas Cotton and Soybean Leaf Tissue.” Arkansas Farm Res. 21:2.

Schreiner, R. P., and C. F. Scagel. 2017. “Leaf Blade versus Petiole Nutrient Tests as Predictors of Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium Status of ‘Pinot Noir’ Grapevines.” HortScience 52(1): 174–184. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI11405-16

Shah, A. N., T. Javed, R. K. Singhal, R. Shabbir, D. Wang, S. Hussain, H. Anuragi, D. Jinger, H. Pandey, N. R. Abdelsalam, R. Y. Ghareeb, and M. Jaremko. 2022. “Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Cotton: Challenges and Opportunities against Environmental Constraints.” Frontiers in Plant Science 13: 970339. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.970339

Singh, H., L. Sharma, L. Johnson, E. Carter, and P. Devkota. 2023a. “Mitigating Nitrogen Losses in Row Crop Production Systems: SS-AGR-471/AG467, 1/2023.” EDIS 2023(1). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-AG467-2023

Singh, K., H. Singh, L. Johnson, E. Carter, L. Sharma, and R. Singh. 2023b. “Plant Growth Regulators as a Management Tool in Cotton Production: SS-AGR-475/AG471, 5/2023.” EDIS 2023(3). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-AG471-2023

Snider, J., G. Harris, P. Roberts, C. Meeks, D. Chastain, M. Bange, and G. Virk. 2021. “Cotton Physiological and Agronomic Response to Nitrogen Application Rate.” Field Crops Research 270: 108194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2021.108194