Everyone likes a good bargain, but when it comes to hay, low price often equates to low nutritional value. Because hay is often sold on a large round-bale basis, savings from the "good bargain" can decrease substantially if there is a negative impact on the cow herd nutritional program. "Bad hay":

- limits feed intake,

- has a low energy value,

- has low protein concentration,

- promotes waste, and

- requires a large amount of supplemental feed to support cow performance.

Increased maturity of the plant prior to hay harvest is likely the largest factor that results in bad hay. The second factor is poor hay field fertility, which creates a lack of critical macro- and micronutrients. This combination of sub-optimal forage management leads to increased plant fiber content, decreased digestibility, and ultimately decreased nutritional value of the hay.

Intake Limitations

Increased fiber content causes intake limitations due to the cow's rumen fill capacity. Likewise, the increased fiber content decreases the digestibility of the hay, which also contributes to the rumen fill limitation imposed by the bad hay. Cow nutrient requirements change throughout the production cycle, but increased nutrient requirements do not equate to greater intake of poor hay.

Energy Limitations

Increased fiber content, which decreases the digestibility of the hay, results in energy limitations. Limited energy availability and intake have an additive effect and negatively impact cow performance. To complicate matters, cow energy requirements increase and reach their peak prior to calving and during lactation. Therefore, bad hay limits cow performance expressed as milk production, body condition score, and subsequent reproduction.

Protein Limitations

Increased fiber content limits the digestibility and availability of protein in the hay. Hay quality compromised by low soil fertility decreases protein content of the forage. A low-protein diet from bad hay also limits the intake of forage due to the deficiency of nitrogen and protein for the rumen microbes that perform the ruminal digestion. Limitations on protein concentration ultimately hinder cow productivity.

Examples of Hay Quality

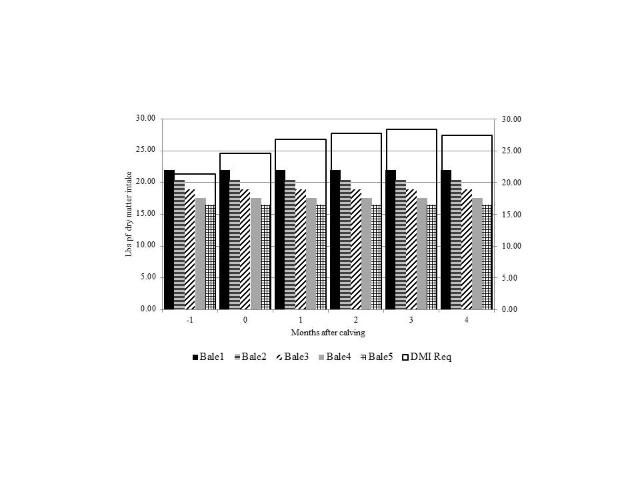

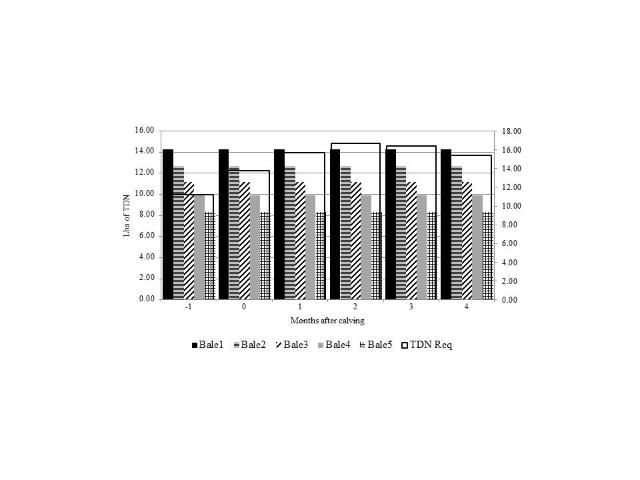

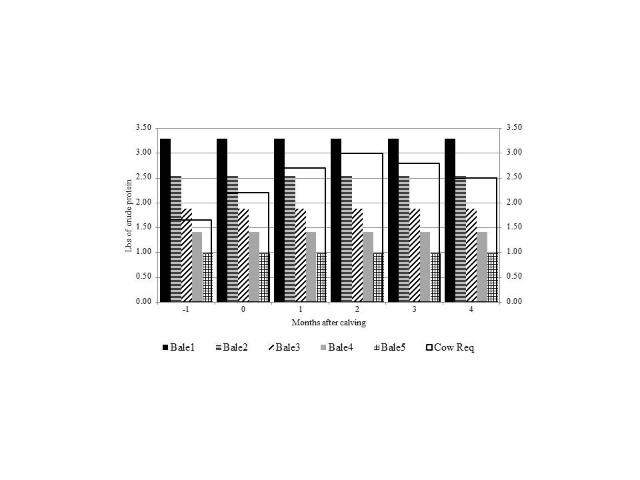

Table 1 describes five different warm-season, subtropical, perennial grass hays of different quality often found in the Southeast. Hay nutritive values range from 60 to 80% neutral detergent fiber (NDF), 50 to 65% total digestible nutrients (TDN), and 6 to 15% crude protein (CP). The figures demonstrate the effect of different hay qualities on estimated cow dry matter intake (DMI) potential (Figure 1), TDN/energy intake (Figure 2), and crude protein intake (Figure 3) relative to the requirements of a 1,200-lb. cow with average milk potential (20 lb./day) during the critical month leading up to and following calving.

Credit: Matt Hersom, UF/IFAS

Credit: Matt Hersom, UF/IFAS

Credit: Matt Hersom, UF/IFAS

The DMI potential is determined using the following equation: DMI, lb. = (cow bodyweight x 1.1) / NDF. Figure 1 demonstrates that hay with greater NDF has decreased DMI potential, often falling well below that of the DMI predicted to meet maintenance requirements, and proving especially inadequate after calving. Hay intake potential directly relates to the supply of energy and protein available to meet the cow's nutrient requirements. Nutrient supply is calculated by the following equation: TDN or CP, lb. = (DMI x % nutrient concentration) / 100. The energy supply predicted by TDN content of the hay is presented in Figure 2. All hays, except bale 5, met cow energy requirements 11 months after calving. Only bale 1 is capable of meeting cow energy demands for four of the six critical months; the other hays do not have enough available energy to meet the cow's energy requirement. Protein supply (Figure 3) is adequate for bale 1 during all six months, bale 2 for three of the six months, and bale 3 for one month. Bales 4 and 5 are unable to meet the protein requirement of a cow during any of the critical months of production.

Hays frequently produced and purchased in the Southeast are quite limiting for cow intake, energy supply, and protein supply. Bale 1 meets energy and protein requirements and does an adequate job maintaining a cow. Depending on the supplement chosen to complement bale 1, supplement needs could be as low as 1 lb. of corn or 5 lb. of soybean hulls to meet energy needs during the critical six-month period when protein is always sufficient. Bale 2 does a fair job, but it lacks sufficient energy and protein, which could be met by 3 lb. of corn to 6 lb. of soybean hulls for a number of months. Bales 3, 4, and 5 leave much to be desired. They lack adequate energy and protein to meet the cow's needs and would require 4.5 lb. of corn to 14 lb. of soybean hulls to meet energy requirements. Even so, they would still be deficient in protein, requiring additional supplementation or other higher protein supplements to fully compensate for all deficiencies.

Impact of Bad Hay on Cow Body Condition

Hay that limits cow hay and nutrient intake causes the cow to mobilize body tissue to meet nutrient deficiencies. A cow can only mobilize a limited amount of body fat and muscle to support her production. Mobilization of body fat and muscle leads to decreased body condition score (BCS) over time. BCS below the pivotal BCS of 5 leads to decreased cow productivity and reproductive performance. The limited intake and energy supply in the example hays result in BCS loss from 5 to 4 in as few as 25 days for bale 4 one month before calving. In contrast, a one-unit BCS loss could take as long as 217 days for bale 1 starting in month 4 after calving. The duration of hay feeding varies across the Southeast and among beef cattle enterprises. The opportunity to utilize winter annuals and early grazing of spring/summer pastures can minimize the effect of bad hay on cow performance. The conclusion is that bad hay results in rapid cow BCS loss at critical times of the production cycle.

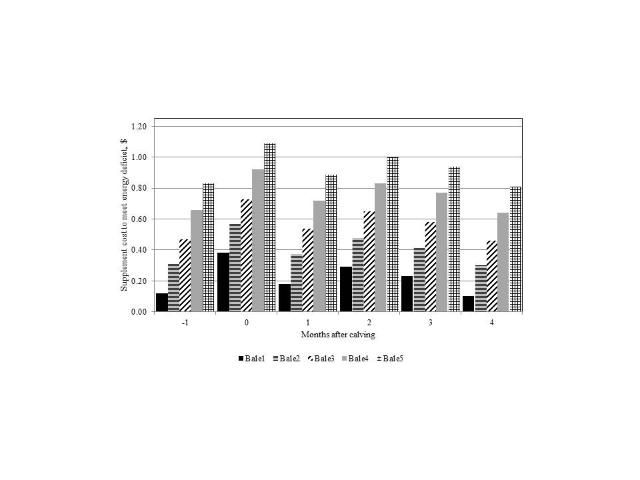

You can find the direct cost of bad hay if you have the forage tested for nutrient quality. It is important to know the true quality of the hay and fix any problems with it by purchasing supplements to fill the nutrient deficiencies. Supplemental feeds can fix the intake limitation and offset energy and protein deficiencies. The severity of the intake, energy, and protein deficiencies and the cost of the supplements determine the cost of fixing bad hay. Figure 4 shows the estimated supplemental feed cost to meet the energy deficit associated with each of the hays. Supplement cost increases with decreasing hay quality. Similarly, supplement costs increase near the calving period and initiation of lactation. The indirect cost of bad hay has negative effects on cow performance, such as lower pregnancy rates and weaning weights of calves.

Credit: Matt Hersom, UF/IFAS

Limitations on hay intake and deficiencies in energy and protein from bad hay lead to increased costs associated with hay feeding. The hay cost, hay waste as result of poor-quality hay, and additional supplementation cost all add up and decrease enterprise profitability. Bargain hay ultimately costs beef cattle producers twice, first when the hay is purchased and again when it is used as feed.