Introduction and History

Viburnum sp. is an important woody ornamental crop for nursery growers in Florida. The main varieties grown in central Florida are V. suspensum (Sandankwa viburnum), V. odoratissimum (sweet viburnum), and V. obovatum (Walter’s viburnum). Viburnums are quick-growing shrubs that reach an average height of about 30 ft if left unmanaged. They produce small white flowers and drupe fruit. They are used popularly in the landscape as hedges or screen plants and are a staple item grown in container nurseries in central Florida. Nurseries propagate viburnum from vegetative cuttings using outdoor stock plants that may appear healthy but often harbor several foliar diseases prevalent in nurseries and landscape environments (Steed et al. 2021). Around 2004, growers began to report severe disease management challenges affecting the production of ornamental Viburnum spp., especially during high-humidity mist propagation (Elwakil et al. 2021). Previously, viburnum cuttings would root with ease with around a 100% propagation success rate and minimal disease issues. When disease started to present itself, propagation success rates could easily drop to 0% success or a total loss of propagation. Reported symptoms included reddish to dark foliar spots followed by blighting and rapid defoliation of cuttings. Young plants, liners that were potted in one- or three-gallon containers, also showed intense disease issues (Figure 1). The problem was originally identified as downy mildew (DM) caused by the oomycete Plasmopara viburni. This fungus is spread with the movement of air and water. High humidity, leaf wetness, plant overcrowding, foggy days, and cool weather (temperatures below 72°F) favor the growth of DM (Salgado-Salazar 2017). Around 2014, growers indicated that common labeled fungicides targeting DM failed to provide acceptable levels of disease management. It was thought that DM had possibly become resistant to fungicides, rendering control unsatisfactory. Research was necessary to determine efficacies of commercially available fungicide chemistries for the management of DM on Viburnum spp. to increase profitability and economic sustainability.

Through a research grant from the Florida Nursery, Growers and Landscape Association, University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) researchers and UF/IFAS Extension Hillsborough County agents conducted studies to determine fungicide efficacy of oomycete fungicides to help nursery professionals produce and maintain a healthy viburnum crop.

Fungicide Efficacy Test on Three-Gallon Viburnum Containers

The first research trial was conducted in July through August using naturally infected Viburnum suspensum plants grown in three-gallon containers at a commercial production plant nursery. It included a water control and 13 fungicide treatments that represented 12 different modes of action (MOA) with the following active ingredients: Cuprofix® Ultra 40D (copper sulfate); Rayora® (flutriafol); Micora® (mandipropamid); Protect™ (mancozeb); Orvego® (dimethomorph + ametoctradin); Subdue Maxx® (mefenoxam); Stature® (dimethomorph); Segovis® (oxathiapiprolin); Adorn® (fluopicolide); Segway® (cyazofamid); Phostrol® (phosphite); Orkestra® (pyraclostrobin + fluxapyroxad); and Postiva® (benzovindiflupyr + difenoconazole). A second research trial was conducted in September through October using the same setup as the first trial, but it focused on seven fungicides with a water control. The fungicides for the second trial were: Protect™, Phostrol®, Cuprofix® Ultra 40D, Orkestra®, Postiva®, Rayora®, and Segovis®.

All fungicide foliar spray treatments were applied twice at a 14-day interval, except for copper sulfate, mancozeb, and phosphite, which were applied weekly. In the second trial, flutriafol was applied as a soil drench as per the manufacturer’s recommendation. Plants were fertilized and overhead irrigated according to grower production standards. The percentage of symptomatic foliage was rated weekly for six weeks to calculate the area under the disease progression curve (AUDPC) (i.e., the amount of disease progress over time).

Surprisingly, downy mildew was not the major driver of the diseases in the plants in the trial. When infected tissues were examined and cultured, multiple fungal pathogens were isolated throughout the growing seasons (spring, summer, and fall), including Plasmopara sp., but also Cercospora sp., Corynespora sp., Colletotrichum sp., and Phyllosticta sp. These caused symptoms of leaf spotting, blighting, and defoliation very similar to those associated with DM that would be extremely difficult to identify with the naked eye. We observed that disease culprits varied in infection rate depending on environmental conditions. Additional surveys of diseased viburnum from other nursery sites also failed to identify Plasmopara sp. in winter and spring of 2021.

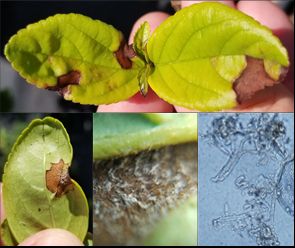

At the beginning of the first trial, the initial survey of viburnum found Plasmopara sp. (downy mildew) (Figure 1), Cercospora sp., and Colletotrichum sp. as the primary pathogens present.

Credit: Dr. Wael Elwakil, UF/IFAS

However, subsequent sampling the next year failed to find any sign of downy mildew. Colletotrichum sp., Corynespora cassiicola, Phyllosticta sp., Phoma sp., and a Pestalotiopsis sp. were recovered from symptomatic foliar tissues (Figure 2).

Credit: Dr. Wael Elwakil, UF/IFAS

Not surprisingly, the fungicides containing ametoctradin, cyazofamid, dimethomorph, fluopicolide, mandipropamid, mefenoxam, and oxathiapiprolin, which specifically target oomycetes (i.e., Plasmopara sp.), failed to reduce disease severity relative to the non-treated control. Benzovindiflupyr, difenoconazole, fluxapyroxad, and pyraclostrobin fungicides, which target true fungi, showed reduction in disease severity.

In the second trial, a subset of seven fungicides was reevaluated on a new crop of younger plants. In this trial, lower disease pressure from Cercospora sp., Colletotrichum sp., Corynespora cassiicola, and Phyllosticta sp. produced more variable results. Only benzovindiflupyr + difenoconazole significantly reduced disease based on the final disease severity rating.

What we learned from these two research studies is that the oomycete-targeting fungicides did not reduce leaf spot severity due to the presence of one or a mixture of other true fungal pathogens. We also learned that contact fungicides were ineffective, likely due to overhead irrigation. Systemic fungicides containing active ingredients used against true fungi were effective in controlling the mixture of foliar pathogens and reducing disease symptoms and spread.

Fungicide Efficacy Test on Viburnum Propagation

In other research studies, disease control in early propagation was investigated. Cuttings of Sandankwa viburnum (Viburnum suspensum) were used in the summer of 2022. Both trials were conducted in July through August, using cuttings from naturally infected Viburnum suspensum plants that were grown in three-gallon containers at a commercial production plant nursery in Hillsborough County. Five fungicides were used: Postiva® (benzovindiflupyr + difenoconazole); Orkestra® (pyraclostrobin + fluxapyroxad); Rayora® (flutriafol); Omega® (fluazinam); and Topsin® 4.5 L (thiophanate-methyl), along with a water control. Fungicides were applied either as a soil drench (10 ml) to cuttings following the application of rooting hormone, or as dip treatment to prepared cuttings followed by the application of rooting hormone and planting. Per standard nursery practice, cuttings were stuck in potting medium (50% peat: 50% perlite) on June 21, 2022, in liner trays. Trays were placed immediately under an overhead mist system (four-second water cycle every six minutes) to keep leaves hydrated. After an initial period of two weeks, cuttings were rated for disease incidence and severity on a weekly basis. The percentage of symptomatic foliage was rated weekly for six weeks to calculate the AUDPC or disease severity over time. Leaf tissues were sampled periodically for disease identification. Plants were removed after six weeks, given a final assessment on week seven, and uprooted to assess root length and root biomass (fresh and dry).

During the course of the experiments, fungi were isolated to determine causal agents. The results indicated the presence of multiple pathogens in both trials. As in the previous nursery trials, Colletotrichum sp. was the most abundant, but others including Cercospora sp., Corynespora sp., and Phyllosticta sp. were observed causing symptoms of leaf spotting, blighting, and defoliation on propagative cuttings.

Both drench-applied and dip-applied fungicides helped reduce final leaf spot severity. For drench-applied fungicide treatments, Postiva® and Orkestra® significantly reduced final leaf spot disease severity by more than 50% compared to the water control. In addition, Postiva® and Orkestra® prevented leaf spot severity from increasing over time, relative to the control and other ineffective fungicide treatments. For the dip-applied fungicide treatments, Postiva®, Orkestra®, Rayora®, and Omega® all reduced final disease severity by 57% on average compared to the control. The same four treatments also prevented leaf spot severity from increasing over time, compared to the control.

Drench-applied fungicide treatments had a significant effect on cutting vigor based on root length and root biomass. Rayora® resulted in cuttings with the shortest root length, and lowest fresh and dry root biomass compared to the control and the other fungicide treatments. Interestingly, dip-applied fungicide treatments did not have a significant effect on cutting vigor; they produced liner plants with roots that were on average 13% longer with 18% and 13% greater fresh and dry biomass, respectively, compared to drench-applied fungicide treatments.

Fungicides applied to propagative cuttings as either a dip treatment prior to planting or as a drench treatment following planting benefited leaf spot disease control during liner production. As in the previously conducted nursery trials, Orkestra® and Postiva® were the most effective at controlling the diverse foliar diseases observed on the cuttings. Meanwhile, the other fungicide treatments were more variable depending on whether they were applied as a dip or as a drench. For example, Ryora® and Omega® both appeared to perform better as a dip rather than as a drench. This would make sense for Omega® (fluazinam), which is a contact fungicide, but Ryora® (flutriafol) is a systemic fungicide. Topsin® and Omega® were included in these trials as broad-spectrum fungicides that have shown success against similar fungal pathogens on other crops. On average, drench-applied fungicide treatments appeared to have a larger negative impact on root development compared to other treatments, including the controls that were treated with water. Fungicides can have profound negative impacts on plant growth. However, the observed differences in the water-treated controls suggest that the effect was likely due to the drench applications diluting the rooting hormone applied to the propagative cuttings prior to planting. In the other trial, the rooting hormone applied to the cuttings had been dipped in a fungicide solution, which did not show a negative impact on the root system in the control.

Overall, we found in the propagation studies that fungicide applications during propagation seem promising to control leaf spot diseases, but they are not curative. If these liners were potted into containers, we would still have significant disease problems to deal with in the growth phase. Due to overhead irrigation and high humidity levels during growth, plants would still be at a significant disadvantage compared to noninfected plants grown in optimal conditions with soil-applied water.

Best Management Practices for Producing Viburnum in the Nursery

The take-home messages are threefold. Firstly, positively identifying the plant pathogen can prepare you for better control of diseases. We found this in our case of confused identity of multiple pathogens present in different mixtures on viburnums during the production season. Secondly, using the correct fungicides for the disease will help, but it is not the overall answer when fighting plant diseases. Keeping clean stock and clean areas of plant production and performing prompt disease scouting will help. Thirdly, sometimes the production system contributes to the problem, and systemic solutions might need to be developed. In terms of potential for disease outbreak, overhead irrigation, high humidity, susceptible plants, and aggressive pathogens form a very bad combination. Changing any one to three of these factors in favor of healthy plants can make a big difference. One of the most important factors to potentially change is overhead water in propagation and container growth. Certain common production methods are adopted because those methods are usually the most efficient and cost-effective; however, they do not always lead to good outcomes as far as diseases are concerned. Therefore, the production of quality viburnum plants will likely remain reliant on fungicides.

Disclaimer

UF/IFAS recommends following all pesticide labels. The label is the law. The selection and use of these products over any other products do not indicate an endorsement.

References

Elwakil, W., S. T. Steed, L. A. Vallad, and G. E. Vallad. 2021. “Viburnum Downy Mildew Control: An Action Plan for Growers.” UF/IFAS Extension Hillsborough County. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8omLE9yu6q4

Salgado-Salazar, C. 2017. “Dossier: Viburnum Downy Mildew.” https://ir4.cals.ncsu.edu/EHC/InvasiveSpecies/Dossier_ViburnumDownyMildew.pdf

Steed, S. T., W. Elwakil, L. Vallad, and G. Vallad. 2021. “Viburnum Foliar Pathogen Identification and Fungicide Efficacies.” Fla. State Hort. Soc. 134: 186–189.