Credit: Wavebreakmedia Ltd/Wavebreak Media/Thinkstock.com

Abstract

This workbook is designed to help firms and individuals become more familiar with the implications of a strategic marketing management program for their businesses. The workbook provides a basic introduction to marketing and strategic marketing management. Readers will learn the basics of a marketing plan and why they need one. Included is a detailed introduction to performing an analysis of the customer, the company, the competition, and the industry as a whole. A major portion of the workbook is devoted to carrying out an effective Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (also known as "SWOT") analysis. This workbook illustrates how analysis can be used to form an effective strategic marketing plan that could increase efficiency and profitability.

The essence of this workbook is to help producers identify their areas of strengths and weaknesses. Once identified, the producer should use this information to make choices between alternative courses of action.

Truly strategic managers have the ability to capture essential messages that are constantly being delivered by the extremely important, yet largely uncontrollable external forces in the market and using this information as the basis for altering the important controllable internal factors of the business to strategically and effectively position the firm for future success.

In addition to identifying strengths and weaknesses, firms would do well to identify factors outside the direct control of managers. In this workbook, these are referred to as opportunities and threats. Careful analysis regarding this combination of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats will help managers position the firm for success.

Introduction

This workbook is designed to help producers become more familiar with how to construct a strategic marketing management program for their business. Originally used at the Grapefruit Economic Workshop, this material was presented by the Florida Cooperative Extension Service and the Indian River Citrus League. The purpose of the workshop was to allow individual producers an opportunity to focus on grapefruit marketing and production strategies. The following workbook has been modified to apply to a wide range of producer groups. The workbook provides a basic introduction to marketing and strategic marketing management. Readers will learn the basics of a marketing plan and why they need one.

The presenters of this workshop challenged producers to consider what their individual firm's marketing strategy was and to identify alternative strategies. Are producers willing and able to change the way they market to improve the profitability of their businesses? Included is a detailed introduction to performing an analysis of the customer, the company, the competition, and the industry as a whole. This workbook shows how these analyses can be used to form an effective strategic marketing plan that could increase efficiency and profitability.

What is marketing?

Let us begin with a definition of marketing. There are many different definitions of marketing. For our purposes, we define marketing (Wysocki 2001) as "the identification of customer wants and needs, and adding value to products and services that satisfy those wants and needs, at a profit."

Please note this definition has three components: (1) the identification of customer wants and needs, (2) firms must add value that satisfies the wants and needs of customers, and (3) firms must make a profit to be sustainable in the long run.

Marketing does not just occur between harvesting, packing, and consumption. Effective marketing in today's changing food system demands that producers also take on a marketing approach to production and shipping.

What is a marketing plan?

A marketing plan is a written document containing the guidelines for the organization's marketing programs and allocations over the planning period (Cohen 2001). Please note that a strategic marketing management plan is a written document, not just an idea. Prior successes or failures are incorporated into the marketing plan. That is, effective marketing managers learn from past mistakes. A marketing plan requires communication across different functional areas of the firm such as operations, human resources, sales, shipping, and administration. Finally, marketing promotes accountability for achieving results by a specified date. Just like an effective goal, an effective marketing plan will be measurable, specific, and attainable.

Strategic Marketing Management

There are at least four goals of strategic marketing management that need to be understood by those wishing to use strategic marketing management to craft profitable strategies:

- To select reality-based desired accomplishments (e.g., goals and objectives)

- To more effectively develop or alter business strategies

- To set priorities for operational change

- To improve a firm's performance

Reality-based accomplishments are shaped by the level of understanding decision makers have regarding the external factors outside of their control and the internal factors under their control. Proper use of this newly acquired knowledge of internal and external factors will lead to more effective business strategies. Strategy, by definition, means decision makers must make choices, and that means setting priorities for operational change. Conducting a strategic marketing management planning exercise should be more than just an exercise. Therefore, the goal of effective marketing management is to improve a firm's performance.

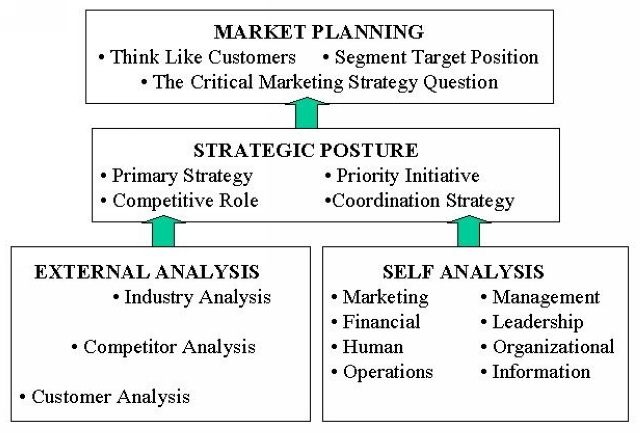

Figure 1 illustrates the strategic marketing management model that is discussed in this workbook. The model is divided into three levels: external/self analysis, strategic posture, and market planning. External/self analysis will receive the majority of attention in this workbook, while strategic posture and market planning will be given a brief overview.

External Analysis Components

External analysis involves an examination of the relevant elements external to your organization that may influence operations. The external analysis should be purposeful, focusing on the identification of threats, opportunities, and strategic questions and choices. The danger of being overly descriptive must be guarded against. It is easy to get caught up in an exhaustive descriptive study, at considerable expense, with little impact on strategy and long-run profitability. It is not uncommon to generate page after page of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats facing your business, especially if management involves the entire organization in the process. This brainstorming type of activity is useful and may encourage buy-in from associates and management throughout your organization, but at some point this list of self (internal) and external factors must be boiled down to the most critical strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats facing the firm (Aaker 1995). The components of external analysis include:

- Customer analysis is the identification of the market segments to be considered, as well as the motivations and unmet needs of potential customers identified.

- Competitor analysis is the identification of strategic groups and their performance, image, and culture, as well as the identification of competitor strengths and weaknesses.

- Industry analysis is the uncovering of major market trends, key success factors, and the identification of opportunities and threats through the analysis of competitive and change forces (e.g., distribution issues, governmental factors, economic, cultural, demographic scenarios, and information needs) (Aaker 1995).

External Analysis Output

You might be wondering what kind of information can be garnered from an external analysis of the factors affecting your firm. An effective external analysis will lead to identification and understanding of the opportunities and threats facing the organization arising out of customer, competitor, and industry analyses.

The following is a definition of opportunities and threats:

- Opportunities are those external factors or situations that offer promise or potential for moving closer or more quickly toward the firm's goals. For example, changing consumer preference for convenience may be an opportunity for your firm.

- Threats are those external factors or situations that may limit, restrict, or impede the business in the pursuit of it goals. For example, new regulations may raise the cost of production, resulting in a threat to your profitability.

The most efficient way to assess the external opportunities and threats facing your organization is to conduct a "brain-storming" session with people from across your organization. You may be surprised at the number of different insights that can arise with this type of exercise. Remember, if the item being considered is beyond the control of the firm, then it is truly external (e.g., an opportunity or threat). If the item being considered is under the control of the firm, then it should not be considered external, but rather should be considered internal to the firm (e.g., a strength or a weakness).

Customer Analysis

Customer analysis involves the examination of customer segmentation, motivations, and unmet needs (Aaker 1995). One could argue that the material presented in this section belongs under the market planning portion of the strategic marketing management model. The following components of customer analysis are discussed here as part of the "external" analysis component of the model:

- Market segmentation is the identification of your current and potential customers (Wedel 1998). In today's food system, market segmentation must include current and potential ultimate consumers of your product/service. For example, a fresh grapefruit producer could identify a number of potential market segments such as produce wholesalers, food service distributors, retail grocery buyers, roadside stand customers, and gift fruit buyers.

- Customer characteristics and purchasing hot buttons provide the information needed to decide whether the firm can and should attempt to gain or maintain a sustainable competitive advantage for marketing to a particular market segment (Lehmann and Winer 1994). For example, retail grocery buyers of fresh grapefruit, who purchase in large quantities, need grapefruit that are labeled with UPC codes, and they require a supplier to be able to meet their supply needs when they order.

- Unmet needs may represent opportunities for dislodging entrenched competitors (Aaker 1995). For example, fresh fruit processors may be looking for effective ways to create whole-peeled grapefruit in order to utilize more grapefruit in their overall fruit purchasing program.

In Table 1, you are asked to take a few minutes to identify as many customer market segments as you can for your particular industry. For each customer market segment, state the customer characteristics and their purchasing hot buttons. Indicate whether the characteristics represent an opportunity (O) or threat (T) to your firm. Cite evidence why the characteristic is an opportunity or a threat to your organization.

Competitor Analysis Components

Competitor analysis can include a multitude of parts. We limit our competitor focus to the following:

- Who are your competitors? Competitors may be firms in your same industry or they could be firms in other industries that your customers view as providing acceptable alternatives for your product or service.

- What does each competitor do well? How about your competitors' image and personality? That is, how are your competitors positioned and perceived in the marketplace? What about your competitors' cost structures? Do competitors have a cost advantage? Finally, what is the marketing attitude of competitors (e.g., least cost, differentiated product, niche market)?

- What does each competitor do poorly? This might provide insight into areas that your company might exploit.

- What can you learn from your competitors? Consider current and past strategies and anticipated future moves by competitors. Where does your firm have a competitive advantage (a strength that clearly places a firm ahead of its competition)? Where is your firm at a competitive disadvantage (a weakness that clearly places a firm behind its competition)?

Please use Table 2 to take a few minutes to identify and to describe the competitors in your industry. For each competitor, state what he does well and what he could do better. Indicate whether your competitors' skills represent an opportunity (O) or threat (T) to your firm. Cite evidence why the skills are an opportunity or a threat to your organization. For example, a competitor might be very efficient at distribution. This may mean that competing against them on the basis of distribution systems may be unwise. This same competitor may have a reputation for below average delivery of customer service. If your firm is well known for customer service or has the potential to deliver superior customer service, this may be an area for your organization to concentrate on to gain competitive advantage.

Industry Analysis

Industry analysis has two primary objectives:

- To determine the attractiveness of various markets (i.e., will competing firms, on average, earn attractive profits or will they lose money?)

- To better understand the dynamics of the market so that underlying opportunities and threats can be detected and effective strategies adopted (Aaker 1995)

A thorough industry analysis will include the following four components:

- Major market trends. Events or patterns that are especially useful if focused on what is changing in the marketplace (Naisbitt 1970). As examples, consider the increasing consumer need for convenience or the long-term decline in per-capita consumption of grapefruit juice and fresh grapefruit facing grapefruit producers.

- Key success factors. Those factors that are the building blocks for success in your industry (Thompson and Strickland 2001). Key success factors arise out of strategic necessities and strategic strengths. For example, a minimum requirement for being in the grapefruit business is to be skilled at all aspects of producing a grapefruit crop.

- Competitive forces. These forces help to explain the potential for profit (or lack thereof) in a particular industry. These forces are based on the work of Michael Porter and include: the threat of entry, supplier and buyer power, the availability of substitutes, and the intensity of rivalry within the industry. For a more complete explanation of these competitive forces, refer to "Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors" (Porter 1980).

- Change forces. Change forces are events outside your organization that shape the way you conduct business. These include government regulations, product and marketing innovations, economic issues, consumer trends, and information needs (Lehmann and Winer 1994).

Please take a few minutes to identify trends and key success factors for your industry in Table 3. For each trend or key success factor, indicate whether it represents an opportunity (O) or threat (T) to your firm. Cite evidence why the characteristic is an opportunity or a threat to your organization.

Competitive Forces Analysis

We have organized Porter's Five Forces model in such a way for you to be able to assess the strength of each of the five forces in your particular industry. For each item in Table 4, circle the number on the scale that best corresponds to your honest assessment of the external situation faced by your firm. Numbers to the left on the scales correspond to situations with greater threats, while numbers to the right correspond to situations with greater opportunities.

How many components of the Five Forces did you assess as opportunities? How many as threats? Later in this strategic marketing management workbook, we compare internal strengths to external opportunities and internal weaknesses to external threats to establish areas of competitive advantage and competitive disadvantage, respectively.

Change Forces Analysis

For each item in Table 5, circle the number on the scale that best corresponds to your honest assessment of the external situation faced by your firm. Then in the space provided, list specific key changes influencing your firm. Less change corresponds to less threatening, but probably fewer opportunities. Greater change corresponds to more threatening, but probably more opportunities. Later in this analysis, we compare internal strengths to external opportunities and internal weaknesses to external threats to establish areas of competitive advantage and competitive disadvantage, respectively.

Self Analysis Components

Having completed a detailed external analysis, now look internally for an understanding of aspects within your organization that are of strategic importance. Components of this part of the self-analysis include assessing the internal strengths and weaknesses of your organization, as well as identifying strategic problems, organizational capabilities, and constraints your firm brings to the strategic marketing management process (Aaker 1995).

We utilize the analysis of the internal strengths and weaknesses to identify strategic problems, organizational competencies (Prahalad and Hamel 1990) and constraints. At this time, it is appropriate to define what is meant by a strength and a weakness:

- Strength. Something a company does well, or a characteristic that gives it an important capability (e.g., Wal-Mart's cost-efficient distribution system).

- Weakness. Something a company does poorly, or a characteristic that puts it at a disadvantage (e.g., Wal-Mart's inflexibility to respond to changes in local marketplace).

Self Analysis Checklist

We utilize a series of checklists to allow you to identify internal strengths and weaknesses, just like we did for external opportunities and threats. For each item in Table 6, circle the number on the scale that best corresponds to your honest assessment of your firm's strength or weakness in the indicated area.

We hope this extensive list helps you to identify internal strengths and weaknesses you may not have thought about in the past. The real value of this analysis takes place when strengths are compared to opportunities and weaknesses are compared to threats; this comparison forms the basis of a SWOT analysis.

SWOT Analysis

SWOT is an acronym that is widely used in the strategic planning literature. SWOT has been so widely and extensively used, that it is difficult, if not impossible, to give credit to any one person for its origination. Each letter of the acronym stands for a different component of this internal/external interface: S=Strengths, W=Weaknesses, O=Opportunities, and T=Threats.

Strengths and weaknesses are internal, while opportunities and threats are external to the firm. The goals of SWOT analysis are twofold:

- To determine your firm's competitive advantages and disadvantages. In what areas do your strengths clearly distance you from your competition? In what areas do your weaknesses clearly put you behind?

- To prioritize the firm's opportunities and threats. In what areas do your strengths match or mismatch your opportunities? In what areas do your weaknesses make you increasingly vulnerable to threats?

A competitive advantage is created by the interface of your most important strengths matching with the most viable opportunities. A competitive disadvantage is created by the interface where your most pronounced weaknesses make you even more vulnerable to the most serious threats facing your organization.

To summarize, SWOT analysis generally follows a four-step process. Please note that steps one and two are interchangeable. That is, you can begin the analysis on either an external or internal focus. The key point is that both external and internal analyses need to be done for effective strategic marketing management to take place. This process is listed below:

- Step 1: Conduct competitive and change analyses to uncover potential opportunities and threats.

- Step 2: Make an honest assessment of your firm's strengths and weaknesses in marketing, production, personnel, information systems, finance, management/leadership, and organizational resources.

- Step 3: Determine your competitive advantages and disadvantages.

- Step 4: Prioritize the opportunities and threats.

To make the most out of SWOT analysis, please consider the following statements of fundamental strategic truths, in priority order:

- Use competitive advantages to seize opportunities.

- After exhausting the chances to use competitive advantages, develop internal strengths that give your firm competitive advantages.

- After exhausting "1" and "2" above, work to eliminate competitive disadvantages.

Opportunities and Threats Analysis

Table 7 provides you with a worksheet to assess your firm's five most important opportunities and threats from your own beliefs and from those you identified as part of the external analysis worksheets (Tables 3, 4, and 5). In the final column, cite specific evidence that supports your belief that the item is an opportunity or a threat. Remember, an "opportunity" is any external factor or situation that offers promise or potential for moving closer or more quickly toward the firm's goals. A "threat" is any external factor or situation that may limit, restrict, or impede the business in the pursuit of its goals.

Strengths and Weaknesses Analysis

Table 8 provides you with a worksheet to assess your firm's five most important strengths and weaknesses from your own beliefs and from those you identified as part of the self-analysis worksheets (Table 6). In the column marked "Rank", provide a numerical ranking of the top five strengths and weaknesses. Place a "1" beside the top-priority strength and top-priority weakness. In the final column, cite specific evidence that supports your belief that the item is a strength/competitive advantage or weakness/competitive disadvantage.

Strategic Marketing Management Analysis

"The final analytical task is to zero in on the strategic issues that management needs to address in forming an effective strategic action plan. Here, managers need to draw upon all prior analysis, put the company's overall situation into perspective, and get a lock on exactly where they need to focus their strategic attention" (Thompson and Strickland 1995). Having gathered all this data, it is now time to put the analysis together in a way that will help your firm craft a long-term strategy. In Table 9, you are asked to answer a series of five questions that rely on your ability to use information obtained from earlier analysis. Please take a moment to answer the questions in Table 9.

Although this SWOT process was quite detailed, and at times repetitive, we hope you found the process insightful and useful. Having completed a thorough SWOT analysis, it is time to use this information to begin crafting a strategic posture.

Strategic Posture Components

SWOT provides the foundation for an effective strategic posture. A strategic posture is a set of decisions that

- Expresses how management intends to achieve a firm's long-term mission, vision, and objectives

- Commits management to a way of achieving competitive advantage

- Springs from awareness of the firm's internal strengths and weaknesses and its external opportunities and threats

- Unifies short-term operational plans and decisions

A fair question to ask would be why should one care about strategic posture? A strategic posture:

- Creates a bridge between the broad intentions of long-term vision and objectives and the specific actions needed for implementation

- Demands that you make choices about what you plan to do—you cannot be all things to all people

- Requires different capabilities and resources for different postures—there are a lot of strategic combinations to choose from; and strategic postures can be developed for the whole firm, a business unit, or for a department

A complete strategic posture includes decisions in at least four areas: primary competitive strategy, competitive role, priority strategic initiative, and vertical coordination strategy. Each of these areas is discussed in upcoming sections of this workbook

Primary Competitive Strategy

Firms can chose from four generic primary competitive strategies. These strategies are adapted from the work of Michael Porter (1980), David Aaker (1995), and others:

- Price Advantage (overall cost leadership) is a price-driven strategy based on basic products/services offered to a broad market (e.g., Sam's Club).

- Quality/Features Advantage (broad differentiation) is a quality-driven strategy based on specialized products and services offered to a broad market segment (e.g., Publix).

- Market Focus Advantage (focused low cost and focused differentiation) is a customer-driven strategy based on specialized products and services offered to a specially targeted (niche) market (e.g., Aldi's).

- Total Quality Management (TQM) Advantage (best cost provider) is a value-driven strategy based on continual innovation in product, price, and process (e.g., Saturn).

It is rare that a firm excels at more than one of the primary competitive strategies. The characteristics that make one of the above strategies effective are likely to reduce the effectiveness of another primary competitive strategy. Remember, it is hard to be all things to all people.

Competitive Role Strategy

Once a firm has decided to pursue a primary competitive strategy based on overall cost leadership, broad differentiation, focused differentiation, or best cost provider, a competitive role strategy must be chosen. That is, a decision must be made how to best position the firm, given the primary competitive strategy that has been chosen. There are four competitive role strategies that can be chosen:

- Leader. The largest market share and/or initiator of change that causes others to respond and follow their lead (e.g., McDonald's)

- Follower. An adopter and adapter of successful strategies from others (e.g., A&W restaurants)

- Challenger. An innovator of strategies that challenge the industry and its normal way of doing business (e.g., Chik-Fil-A)

- Loner. A provider of products/services that fill gaps in the marketplace (e.g., mom-and-pop restaurants)

Just as in primary competitive strategy, it is difficult for a firm to be all things to all people. For example, under Jack Welsh's leadership, General Electric made a commitment to only stay in markets where General Electric would be either first or second in market share. This is an example of a "leader" competitive role strategy.

Priority Strategic Initiative

The next step in developing an effective strategic posture takes place after the primary competitive strategy and the competitive role strategies have been identified. This step is labeled the priority strategic initiative. There are five possible strategic initiatives that firms should consider (Aaker 1995):

- Grow. Expand the size or scope of your business (e.g., Subway).

- Maintain/Defend. Keep what the firm has achieved in size and scope (e.g., McDonald's).

- Reposition. Maintain the firm's size or scope while changing key elements of market position (e.g., IBM).

- Retrench. Reduce the size and scope of the business (e.g., RJR Nabisco).

- Exit. Leave the market (e.g., Saturn).

Each of these strategic initiatives demands a singleness of purpose like the primary competitive strategies and competitive role strategies.

Vertical Coordination Strategies

The final decision to be made concerning a firm's strategic posture is to determine which vertical coordination strategy to choose. Vertical coordination strategies are perhaps best thought of as decisions of how to best handle the buy-and-sell interface that takes place across the entire food system from input supplies to final consumer purchases. The decision maker must consider five possible vertical coordination strategies:

- Spot/Cash Market. A physical market system that forms the traditional way agricultural products have been sold in the United States. Spot markets rely on external control mechanisms, price, and broadly accepted performance standards to determine the nature of exchange. Neither party can influence price or the generic standards (e.g., selling grapefruit to citrus packers on the open market) (Lehmann and Winer 1994).

- Contracting. Marketing contracts are legally enforceable agreements with specific and detailed conditions of exchange. Each participant must agree on specifications that are ultimately enforced by a third party (e.g., a production contract with a citrus processor).

- Relation-Based Alliance. An informal agreement between parties designed for the mutual benefit of both parties. Both parties retain separate, external identity where formal joint-management structure is not present to allow for strong internal control. However, enforcement mechanisms are developed internal to the relationship (e.g., an agreement between a citrus producer cooperative and a citrus processor whereby the cooperative's members agree to sell their entire production to the citrus processor in exchange for prices that average above the spot market average).

- Equity-Based Alliance. Catch-all of many organizational forms, including joint ventures and cooperatives, that involve some level of equity (money, assets, sweat, or emotional). One distinguishing feature is the presence of a formal organization that has an identity distinct from the members with decentralized control. Owners still maintain a separate identity that allows them to walk away (e.g., a citrus producer cooperative).

- Vertical Integration. Having control or ownership of multiple stages of production/distribution (e.g., Tyson Foods in the poultry industry).

Multiple decisions affecting the company must be made when determining company strategy. The combined effect of these decisions will impact the direction in which a company embarks. Overall, there are approximately (4x4x5x5) = 400 potential choices for selecting a primary competitive strategy, competitive role, priority strategic initiative, and vertical coordination strategy combination.

The final part of this workbook introduces motivations for some consumer behavior characteristics and then examines the relationship between a strategic marketing plan and management using three critical marketing concepts. While these topics will only be given superficial treatment in this workbook, additional publications in this series will explore these concepts in greater detail.

The Changing Consumer

It is important to understand the changing needs of consumers when designing your strategic marketing management plan. For each of the following changing consumer needs, please consider their potential impact (positive or negative) on your firm (Lehmann and Winer 1994).

- Overriding desire for quality. Today's consumers demand quality and they are willing to pay for it.

- Bargain hunting by the affluent. Just because the affluent have money does not mean that they are not bargain hunters.

- The buying guideline is selectivity. Consumers demand a multitude of choices, varieties, etc.

- Traditional brand loyalty is fading. This is, in part, due to the increase in the quality of store brands such as Publix brand products.

- The middle line is dropping out. There has been a squeezing out of middle management in corporate America over the last few decades or so with a trend towards society becoming a nation of haves and have-nots (Stevens, Loudon, and Warren 1991).

- Consumers want it now! Convenience and immediate gratification fuel many of today's consumer goods purchases.

- Home entertainment is in style. Consumers are not motivated by price alone. Many of us are willing to spend more for products and services if we can be entertained along the way.

- It's back to the way we were. There is a growing segment of the population that craves life the way it used to be, with simplicity and value being paramount.

- Staying alive. This phrase describes those consumers who are health conscious.

- Cashing out. Consumers who are tired of the "rat race" and want to take up a simpler life.

- Small indulgences. Many consumers are willing to treat themselves to small rewards for accomplishments and milestones reached in their lives.

- Customization. Wanting quality, and wanting it now.

- S.O.S (Save Our Society). S.O.S. refers to consumers who make purchasing decisions based partly on social concerns or causes they support (Lehmann and Winer 1994).

The purpose of looking at the changing consumer is to encourage you to consider the consumer more directly when crafting a strategic marketing management plan.

Three Critical Marketing Concepts

The strategic marketing plan is built around three critical marketing concepts. These concepts are represented by the following acronyms:

- TLC (Think Like Customers)

- CMSQ (Critical Marketing Strategy Question)

- STP (Segment, Target, and Position)

Think Like Customers

"Think Like Customers" (TLC) is a plea for businesses to remember the customer in their decision-making process. To think like a customer is consistent with the viewpoint that "marketing is the whole business as seen from the viewpoint of the customer." Experience and research indicate that all firms have the opportunity to do better at TLC. We are sure you would be able to cite numerous examples from your own life when firms did not practice thinking like their customers. Can you list examples of firms that think like customers? Can you list examples of firms that do not think like customers?

Critical Marketing Strategy Question

In its simplest form, the "critical marketing strategy question" (CMSQ) is: "Why should customers purchase your firm's products/services over those of your competitors?" This may sound like a simple question. You may be surprised at how difficult it can be to come up with good reasons (reasons that differentiate you from your competition) why people/firms should purchase your products/services. Table 10 asks you to list all the reasons why you believe customers should buy products/services from your firm.

Based on the list above, select the first and second most important reasons why customers buy from you. That is, in essence, your answer to the critical marketing strategy question.

Segment, Target, and Position

"Segment, Target, and Position" (STP) is one of the basic building blocks of modern marketing (US Small Business Administration 1980). STP strategies should complement a firm's overall generic strategies, consisting of a primary competitive strategy, competitive role strategy, strategic initiative, and vertical coordination strategy.

Market Segmentation is the basic recognition that every market is made up of distinguishable segments consisting of buyers with different needs, buying styles and responses. In essence, this is the process of identifying all possible markets to which your product or service could be offered. Although there are many ways to segment a market, these are beyond the scope of this workbook.

No single offer or approach will appeal to all buyers. This means that companies must make a choice regarding which markets, out of all the possibilities, they wish to serve. Target market selection is the act of developing measures of segment attractiveness and selecting one or more of the identified segments to enter and emphasize. Table 11 asks you to make a list of all the possible target markets for your product or service that you would consider entering.

Based on the list in Table 11, select the two most attractive market segments to serve. Keep in mind your firm's competitive advantages and disadvantages when stating your answer. These will become your target markets.

- ____________

- ____________

The final step of the STP strategy involves the establishment of a positioning strategy. Positioning includes decisions in product, price, distribution, and promotion. Each of these is the subject of a workbook unto itself. Remember, once you have determined the one or two markets you want to target, you need to decide how to position your product or service in the minds of potential customers, relative to your competitors.

Conclusion

We hope you found value considering the strategic marketing management process as identified in this workbook. Please remember that the strategic marketing management process is not meant to be used once every five years, only to collect dust on some manager's shelf. To be effective, this process requires the support of upper management and the involvement and commitment of the entire company.

References

Aaker, D.A. 1995. Strategic Market Management, Fourth Edition. New York: John Wiley.

Cohen, W.A. 2001. The Marketing Plan. New York: Wiley.

Drucker, P.F. 1974. Management, Tasks, Responsibilities, and Practices. New York: Harper and Row.

Lehmann, D.R. and R.S. Winer. 1994. Analysis for Marketing Planning, Third Edition. Burr Ridge, IL: Richard D. Irwin, Inc.

Naisbitt, J. 1982. Megatrends: Ten Directions Transforming Our Lives. New York: Warner Books.

Porter, M.E. 1980. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. New York: Free Press.

Prahalad, C.K. and G. Hamel. 1990. The core competence of the corporation. Harvard Business Review. 68(3) p. 79-91. Retrieved from Business Source Premiere database.

Stevens, R.E., D.L. Loudon, and W.E. Warren. 1991. Marketing Planning Guide. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press.

Thompson, A.A. and A.J. Strickland. 2001. Crafting and Executing Strategy: Text and Readings, Twelfth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Thompson, A.A. and A.J. Strickland. 1995. Crafting and Executing Strategy: Text and Readings, Sixth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill.

US Small Business Administration. 1980. Marketing Strategy. Washington, DC: US Small Business Administration.

Wedel, M. and W.A. Kamakura. 1998. Market Segmentation: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic.

Wysocki, A.F. and F.F. Wirth. 1999. Assessing the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats Involving Your Business. Workbook prepared for the Grapefruit Economic Workshop, UF/IFAS Indian River Research and Education Center, Fort Pierce, FL.