Introduction

Farmworker coalitions provide an informal, non-governmental path for farmers and farmworkers to assemble and advocate for their rights in a safe and accessible manner. The purpose of this publication is to educate established entities such as Extension on the importance of farmworker coalitions and their role in the facilitation and development of these coalitions. Coalitions provide a holistic approach to the improvement of working and living conditions for farmworkers, and take into consideration community partners, policymakers, farmers, and farmworkers themselves. Coalitions play a vital role in ensuring the well-being of farmworkers, but their presence amidst widespread adverse conditions such as the COVID-19 pandemic is especially impactful. Although the pandemic has brought with it unique challenges, coalitions have adapted throughout history to fit the needs of farmworkers within many contexts, including the improvement of health equity and access. For example, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) in south Florida advocated for their own rights as farmworkers within an environment which many would consider unlivable (Rosile, Boje, & Herder, 2020). CIW shifted supply chain practices for large investors through their Fair Food Program. This innovative, community-based response involves partnerships among producers, fast food chains, stores, and farmworkers, who work together to secure and maintain sufficient quality of life (Rosile, Boje, & Herder, 2020). Compliance with the Fair Food Program requires that one penny per pound of purchased tomatoes be allocated to farmworkers. Buyers must also follow the Fair Food Program's code of conduct to uphold the rights of farmworkers (Rosile, Boje, & Herder, 2020).

Credit: unsplash.com

How are farmworker coalitions formed and maintained?

Rigorous research over the past several years has addressed the creation of coalitions and the sustainability of their practices. Coalitions stem from recognized needs within a community or population and aim to address these issues. Once the mission has been identified, the process of recruiting members and establishing an organizational structure begins. Foster-Fishman et al. developed a comprehensive framework that outlines the entirety of this process, placing special focus on the capacity of members (Foster-Fishman, Berkowitz, Lounsbury, Jacobson, & Allen, 2001). When in the developmental stage of coalition formation, Foster-Fishman et al. stress the importance of considering the capacity of potential members taking part in coalition practices when developing an infrastructure and planning coalition activities (Foster-Fishman et al., 2001). These considerations relate directly to collaborative work and completion of integral tasks within coalition operations (Foster-Fishman et al., 2001). After determining the core mission, coalitions should reach out to those within the population and identify accessible logistics of meetings and activity structures (Foster-Fishman et al., 2001). Additionally, Van Dyke and Amos identified key factors in the success of coalitions: social ties; conducive organizational structure; ideology, culture, and identity; commitment and trust; institutional environment; and resources (Van Dyke & Amos, 2017). Social ties, commitment, and trust work together to create a sense of community, safety, and engagement among coalitions. Social ties provide motivation to get involved in coalitions, and subsequent development of commitment and trust can bolster the longevity and maintenance of these coalitions. The cultivation of social ties can occur both before and during coalition involvement. This occurs through a series of culturally competent activities that improve understanding among members. The specifics of these activities depend on the population represented within the coalition. A suitable organizational structure is vital to the formational integrity of a coalition. Rojas and Heaney (2008) outlined the importance of having a broad, multi-issue mission at the center of a coalition. This allows for more attraction to a coalition and continued motivation within it, furthering the coalition's impact and attracting a wider breadth of stakeholders. Additionally, when there is a shared ideology, culture, and identity within a coalition, there is an overall increase in the likelihood of success and longevity (Van Dyke & Amos, 2017). These conditions, along with political challenges and opportunities, point to the importance of the institutional environment. The societal context of a coalition will guide the group’s ability to harness opportunities, or to bond over obstacles and work through them together (Van Dyke & Amos, 2017). Lastly, the gaining or depletion of resources due to participation in a coalition should be considered from the perspectives of members and those who initially started the coalition (Van Dyke & Amos, 2017).

Credit: unsplash.com

Rosile et al. (2016) conceptualized the composition and activities within the successful Coalition of Immokalee Farmworkers. These principles and practices reflected the previously outlined considerations. However, special attention was paid to the role of leadership and ways this can be harnessed to have an even greater impact. Ensemble leadership, which is based on the history of Indigenous cultures, was applied within the Immokalee coalition. This includes the integration of collectivism, shared leadership, dynamic storytelling, and a decentralized, heterarchical structure (Rosile, Boje, & Claw, 2016). Each of these pieces emphasizes the importance of sharing in successes, failures, and the coalition’s mission. Alongside this comes the importance of worker-to-worker training. This creates an accessible and fair way to educate farmers and farmworkers about their rights, as those educating have experience in farmwork themselves (Rosile, Boje, & Claw, 2016). The act of "together telling" was also outlined within the context of CIW as a key practice that ensures that no individual speaks on behalf of another (Rosile, Boje, & Herder, 2020). This involves consistently directing questions from journalists or interviewers to those to whom the questions pertain. Additionally, Rosile et al. explain the importance of having attentive, accurate interpreters so that spoken responses can be understood by everyone present (Rosile, Boje, & Herder, 2020).

Farmworker Coalitions and COVID-19 Protections

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified the health inequity experienced by farmworkers in the southeastern United States. Housing is often inadequate for this population, and overcrowding, poor ventilation, and lack of sanitation in living environments have become even more of an issue during the COVID-19 pandemic (Handal, Iglesias-Ríos, Fleming, Valentín-Cortés, & O’Neill, 2020). Migrant farmworkers are disproportionately affected by housing conditions because they are more likely than non-migrant farmworkers to live on property provided by their employer (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.). These environmental factors increase the likelihood of COVID-19 infections because they make way for mass contamination and continued spread of the virus. Additionally, these conditions increase the likelihood of developing other illnesses and diseases such as asthma, which further increase vulnerabilities to COVID-19. Issues with working conditions are similar to housing concerns, including employers’ failure to provide personal protective equipment (PPE) and failure to enforce PPE use (Damalas & Abdollahzadeh, 2016). Avoiding practices such as mask wearing increases the likelihood of COVID-19 infection (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). Unfortunately, direct reporting from migrant farmworkers has uncovered an all-too-common fear for their well-being and employment if farmworkers were to expose their employer as noncompliant with CDC guidelines (Handal et al., 2020). For similar reasons, farmworkers also experience apprehension when it comes to seeking out medical assistance (Haley, Caxaj, George, Hennebry, Martell, & McLaughlin, 2020). A general lack of health insurance enrollment among this group further compromises farmworker health (Becot, Inwood, Bendixsen, & Henning-Smith, 2020). Farmworker coalitions provide a community-based approach to advocacy. This demands adherence to health protocols within farmwork and housing, and elimination of barriers to professional medical assistance. Coalitions can advocate for employment insurance, so that when farmworkers feel safe in seeking out medical care, they have affordable access to these services (Haley et al., 2020). Haley et al. (2020) point to the role of coalitions in advocating for clearly outlined policies and procedures which allow farmworkers to seek out medical care without fear of losing their jobs or facing negative consequences from their employer.

Credit: unsplash.com

Lack of access to accurate COVID-19 information and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reporting has left farmworkers unsure of how to remain safe during the pandemic and what to believe (Tutor Marcom, Freeman Lambar, Rodman, Thomas, Watson, Parrish, & Wilburn, 2020). North Carolina combatted this issue, as well as lack of access to testing sites and PPE, through partnerships from an enacted work group. This coalition was put into place to monitor and address any farmworker needs associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, utilizing community partnerships like Cooperative Extension to fill gaps in assistance (Tutor Marcom et al., 2020). Many Americans received governmental assistance to stay afloat as part of an effort to offset the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, since many farmworkers are undocumented, these financial supports were not available (Beatty, Hill, Martin, & Rutledge, 2020). Non-governmental coalitions have the power to raise funds specifically for undocumented noncitizen adults and their families, providing necessary assistance during this time of crisis. They may also advocate for policy shifts to include this population in future governmental relief efforts.

UF/IFAS Extension

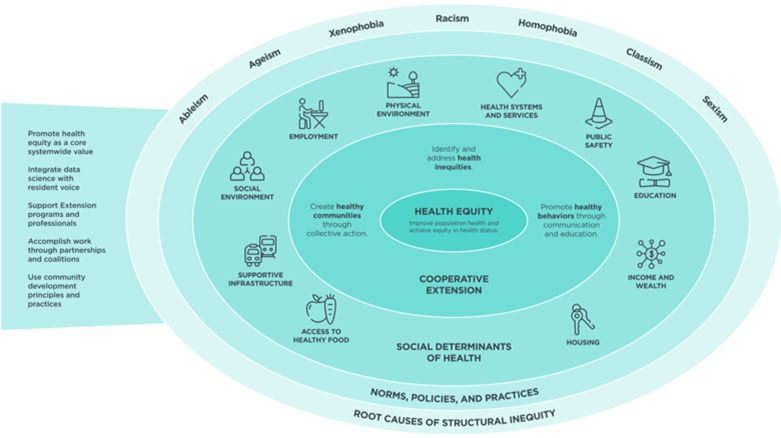

Cooperative Extension's newly introduced National Framework for Health Equity and Well-Being outlines the importance of supporting communities on their journey to health equity status (Burton et al., 2021). Members of the population leading and carrying out farmwork are an integral piece of this health equity puzzle. With growing concerns related to the health of farmworkers during the COVID-19 pandemic, this framework guides efforts in identifying and addressing social determinants of health through community-based partnerships. Within their report outlining the National Framework for Health Equity and Well-Being, Burton et al. (2021) demonstrated how to connect Extension, associated community councils, and coalitions to work together, describing Extension’s role as, “…convening, facilitating, managing, supporting, resourcing, and leading.” Additionally, Extension trainings and educational materials should be created to outline the value of farmworker coalitions and equip the community to form and maintain coalitions of their own.

Credit: Burton et al. (2021)

Recommendations

Sustainability

To combat the various inequities faced by farmworkers, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, the formation of sustainable coalitions is vital. This will require the support and contributions of farmers, farmworkers, policymakers, and informed community partners.

Considering the Bigger Picture

Stakeholders must consider the health of farmworkers as not only an ethical matter, but as a way to avert further farm operational issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., food supply chain shortages) (Aday & Aday, 2020). Meatpacking facility operations have been particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 infection, with the presence of beef packing facilities increasing county transmission rates by 110%; pork, by 160%; and chicken, by 20%—thus impacting the health of populations and the efficiency of meat supply chain operations (Saitone, Schaefer, & Scheitrum, 2021).

Key Partnerships

The formation of farmworker coalitions should be encouraged and supported through community advisory boards across the southeastern United States. This provides a streamlined approach to coalition creation, as well as established relationships and direct access to key partners. This innovative approach paves the way for collaborative coalitions that improve agricultural working conditions in a holistic manner.

Broadening the Focus

Use of a broader, multi-issue approach to coalition operations can allow engagement of more roles and perspectives with many different missions under a singular vision to increase farmworkers’ quality of life. These coalitions should exemplify a culturally competent approach which uplifts the voices of farmers and farmworkers themselves, recognizing that they are the experts.

References

Aday, S., & Aday, M. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on the Food Supply Chain. Food Quality and Safety, 4(4), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1093/fqsafe/fyaa024

Beatty, T., Hill, A., Martin, P., & Rutledge, Z. (2020). COVID-19 and Farm Workers: Challenges Facing California Agriculture. ARE Update, 23(5), 2–4. https://s.giannini.ucop.edu/uploads/giannini_public/12/35/1235dbbd-cb7d-42fa-b1a9-7ec40cd22ecb/v23n5_2.pdf

Becot, F., Inwood, S., Bendixsen, C., & Henning-Smith, C. (2020). Healthcare and Health Insurance Access for Farm Families in the United States during COVID-19: Essential workers without essential resources? Journal of Agromedicine, 25(4), 374–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924X.2020.1814924

Burton, D., Canto, A., Coon, T., Eschbach, C., Gutter, M., Jones, M., Kennedy, L., Martin, K., Mitchell, A., O’Neal, L., Rennekamp, R., Rodgers, M., Stluka, S., Trautman, K., Yelland, E., & York, D. (2021). Cooperative Extension’s National Framework for Health Equity and Well-Being. Extension Committee on Organization and Policy https://www.aplu.org/wp-content/uploads/202120EquityHealth20Full.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2023.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Workplace Prevention Strategies. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/guidance-agricultural-workers.html

Damalas, C. A., & Abdollahzadeh, G. (2016). Farmers' Use of Personal Protective Equipment during Handling of Plant Protection Products: Determinants of Implementation. Science of the Total Environment, 571, 730–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.07.042

Foster-Fishman, P. G., Berkowitz, S. L., Lounsbury, D. W., Jacobson, S., & Allen, N. A. (2001). Building Collaborative Capacity in Community Coalitions: A Review and Integrative Framework. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(2), 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010378613583

Haley, E., Caxaj, S., George, G., Hennebry, J., Martell, E., & McLaughlin, J. (2020). Migrant farmworkers face heightened vulnerabilities during COVID-19. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 9(3), 35–39. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2020.093.016

Handal, A. J., Iglesias-Ríos, L., Fleming, P. J., Valentín-Cortés, M. A., & O’Neill, M. S. (2020). “Essential” but Expendable: Farmworkers during the COVID-19 Pandemic—The Michigan Farmworker Project. American Journal of Public Health, 110(12), 1760–1762. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305947?casa_token=Kjc0S_rUl4cAAAAA%3AVjb01UzBlxeZZ9N-SLJYv1ySigCjiHRaQuXb6sCQNgbr6rm0JwkLHfMdK7nEWyFSD4hMqRbKhDck

Rojas, F., & Heaney, M. (2008). Social Movement Mobilization in a Multi-Movement Environment: Spillover, Interorganizational Networks, and Hybrid Identities. Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/pdf/3d483d8bc918f15a774d4e9358fd17a2265d354c. Accessed January 23, 2023.

Rosile, G. A., Boje, D. M., & Claw, C. M. (2016). Ensemble Leadership Theory: Collectivist, Relational, and Heterarchical Roots from Indigenous Contexts. Leadership, 14(3), 307–328. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1742715016652933

Rosile, G. A., Boje, D. M., & Herder, R. A. (2020). The Coalition of Immokalee Workers uses storytelling processes to overcome enslavement in corporate supply chains. Business and Society, 60(2), 376–414. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0007650320930416

Saitone, T. L., Schaefer, K. A., & Scheitrum, D. P. (2021). COVID-19 Morbidity and Mortality in US Meatpacking Counties. Food Policy, 101, 102072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102072

Tutor Marcom, R., Freeman Lambar, E., Rodman, B., Thomas, G., Watson, A., Parrish, B., & Wilburn, J. (2020). Working Along the Continuum: North Carolina’s Collaborative Response to COVID-19 for Migrant & Seasonal Farmworkers. Journal of Agromedicine, 25(4), 409–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924X.2020.1815621

U.S. Department of Labor. (n.d.). Findings from the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) 2017–2018: A Demographic and Employment Profile of United States Farmworkers. Report No. 14. JBS International. https://wdr.doleta.gov/research/FullText_Documents/ETAOP2021-22%20NAWS%20Research%20Report%2014%20(2017-2018)_508%20Compliant.pdf

Van Dyke, N., & Amos, B. (2017). Social Movement Coalitions: Formation, Longevity, and Success. Sociology Compass, 11(7). https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12489