Introduction

Volunteers are an integral part of UF/IFAS Extension and nonprofits. Forty percent of charities rely on volunteers. In 2019, 64.4 million adult volunteers contributed 8.8 billion hours of their time to their chosen organizations (NCCS Project Team, 2020). Many factors influence a person’s decision to volunteer for an organization. Civic-mindedness is the most common reason people donate their time (Bang et al., 2009). Other motivations, such as mandatory volunteering, entertainment value, and others’ perceptions of the volunteer, may play a significant role. Predators or thieves may see volunteering as a way to benefit personally. Knowing what drives a person to volunteer can help volunteer coordinators tailor job tasks and their supervisory styles to each person (Hager & Brudney, 2015). Understanding volunteer motives is especially important today. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the volunteering landscape has shifted to increase virtual volunteering. This has opened the door to far more volunteers than in the past. This article describes five unique motivations to volunteer. Management tools are provided for each motivation type in the context of environmental conservation and sustainability programming.

Motivation 1: “It is the right thing to do.”

Civic duty, or a belief in the common good, is one of the most common reasons for volunteering (Clary & Snyder, 1999). Civic-minded volunteers are motivated to work because they believe volunteering is the right thing to do for their community (Shachar et al., 2019). As a result, these volunteers are highly intrinsically motivated (Cloyd, 2017). Civic-minded volunteers are also more likely to join organizations whose mission or programmatic goals align with their values (Clary & Snyder, 1999). Volunteers concerned about environmental conservation may feel they have a personal responsibility to participate in projects related to wildlife protection or land conservation.

Managing Civic-Minded Volunteers

The best way to recruit and retain civic-minded volunteers, or “do-gooders,” is to ensure that their work satisfies their intrinsic desire to help (Tschirhart & Bielefeld, 2012). Recruitment flyers or social media posts should emphasize how the volunteer’s contribution will benefit the community. Volunteer managers can learn about new volunteers’ motivations by talking to them and finding out what the volunteers hope to gain from their experience and what they can contribute. From there, the volunteer manager can find a job that aligns with their values and abilities. For example, suppose a volunteer joins a conservation organization to teach younger generations about recycling. In that case, volunteer managers should assign long-term tasks to complete over multiple sessions. Volunteer commitment to the cause can increase reliability for more complex duties and tasks.

Without appropriate job placement, civic-minded volunteers will likely lose interest in working with the organization (Hager & Brudney, 2015). Civic-minded volunteers are more likely to stay active in an organization if they feel their experience is worthwhile (Bang et al., 2009). Thus, volunteer managers should ensure that volunteers know how the assigned task affects the programmatic outcomes.

Proper training will facilitate a satisfactory volunteering experience, and, in turn, organizational efficacy (Hager & Brudney, 2013). Volunteers want to feel that the tasks align with their skills (Nichols et al., 2019). Otherwise, these civic-minded volunteers may find a different place to donate their time and skills.

Motivation 2: “Because I have to.”

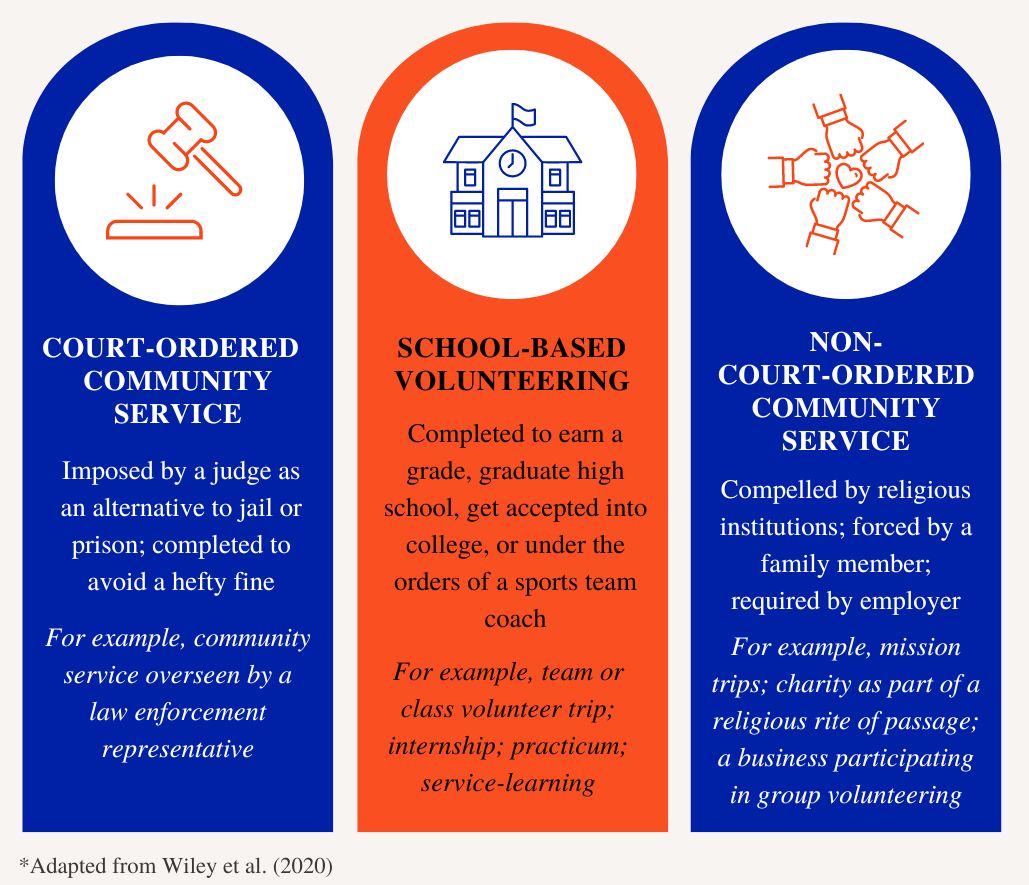

Compulsory volunteers work to meet an obligation to someone or something else. Examples include students who volunteer to meet graduation requirements or people who have a court order to complete community service. Others may feel obligated to their religious institution or a family member. Figure 1 presents these three types of compulsory volunteers and offers examples. Compulsory volunteers push the limits of the definition of “volunteer” because their service is not technically voluntary (Wiley & Evans, 2021). The main concern with compulsory volunteers is that they may lack the motivation other volunteers possess unless there is an external motivator present (Cloyd, 2017). Despite this concern, compulsory volunteers can still be helpful to any organization.

Managing Compulsory Volunteers

With proper management, compulsory volunteers can help an organization meet its goals. When onboarding a compulsory volunteer, volunteer managers should explain the types of tasks in which the volunteer can participate and allow them to choose their assignment. Providing options gives volunteers autonomy, which may lead to higher intrinsic motivation (Cloyd, 2017). Assigned task options should include simple, short-term projects such as litter cleanups, because there is a strong possibility that compulsory volunteers will not continue volunteering after they have completed their obligations.

To ensure compulsory volunteers fulfill their responsibilities, supervisors can keep a closer eye on them, especially when these volunteers are new to the organization (Hager & Brudney, 2015). If the volunteers are not meeting expectations, a supervisor can talk with them to identify ways to help or to keep them engaged. However, it is the volunteer’s responsibility to complete their required work hours. Be upfront about whether or not the assigned tasks will provide enough work to fulfill the volunteer’s needs.

Credit: Adapted from Wiley et al. (2022)

Motivation 3: “I’m just here for the fun!”

Volunteers may give their time because they find volunteering entertaining. People volunteer for cultural events, such as Earth Day benefit concerts or county fairs, to get closer to the action (Nichols et al., 2019). An intense form of volunteering for entertainment is “voluntourism,” where people go on vacations to another country while volunteering to give back, often for environmental or conservation-related purposes (Wearing, 2004). A typical example is a trip to work on an endangered species conservation project, such as lemur preservation in Madagascar. These volunteering experiences tend to be one-time events or trips rather than ongoing engagements.

However, volunteering for entertainment does not always involve international travel. Many people volunteer at local environmental nonprofits, such as the Audubon Society or community gardens. Such activities allow volunteers to spend time outside with others, enhancing the social aspect of volunteering (Patrick et al., 2021). Sports volunteers often report that social benefits were the most common motivation to work the ticket booth or snack stand at a local equestrian event, for instance (Nichols et al., 2019). Given their distinct motivations, volunteers seeking entertainment require unique management techniques to ensure the experience meets their needs.

Managing Fun Seekers

Volunteer managers should assign tasks that fun-seeking volunteers enjoy; otherwise, these volunteers are unlikely to return (Clary & Snyder, 1999). Activities such as trail cleanups are similar to leisurely activities such as hiking, making them the perfect events for volunteers who are looking for outdoor fun. Fun-seeking volunteers are less consistent with attendance than other types of volunteers. However, when volunteering habits are instilled at an early age, such as through 4-H youth programs, people are more likely to continue volunteering as adults (Nichols et al., 2019). For volunteers struggling with consistency, it is best to assign short-term projects that do not require lengthy commitments.

Environmental nonprofits and Extension programs can take advantage of the social motivations and short-term commitment of fun-seeking volunteers for large-scale, group volunteering projects. Teams of volunteers generally complete activities such as removing invasive species or planting native trees, so these tasks may be more socially engaging (Gabbey, 2019). Additionally, many volunteers for environmental programs already enjoy spending time outside in nature (Patrick et al., 2021). As a result, these activities are likely more entertaining for fun seekers. Volunteer recruitment materials should emphasize the task’s enjoyable aspects. By targeting the motivations of entertainment-seeking volunteers, volunteer managers can leverage their enthusiasm in productive ways (Nichols et al., 2019).

Motivation 4: “Look at me!”

For some people, volunteering is a way to impress others, such as a romantic interest, friends, family, or a potential employer. Visibility and recognition are key to leveraging attention-seeking volunteers for good. Attention-seeking volunteers are often interested in public-facing activities, such as managing a booth at a vendors’ fair. Earth Day provides endless opportunities to engage volunteers who want others to recognize them for their contributions. For example, local celebrities or politicians would benefit from the public spotlight at an Earth Day event at a community center or a local school.

Tech-savvy, attention-seeking volunteers can be useful for social media-based “micro-volunteering.” Micro-volunteering includes small, low-effort tasks such as sharing Facebook posts about climate change and endangered species or retweeting advocacy messages about an upcoming legislative climate bill (Mackay et al., 2016). Interactions on their posts can make attention-seeking volunteers feel as though they are getting the recognition they desire among their social media followers.

Managing Attention Seekers

A concern with attention-seeking volunteers is that they may not be interested in the arduous work of volunteering. Instead, these volunteers may only show up occasionally to tell others they volunteer in their free time. To prevent this behavior, volunteer managers should be clear and direct during the interview or orientation about the scope of volunteer responsibilities (Forsyth, 1999). Setting expectations from the beginning allows volunteers to decide if the organization is a good fit for their needs.

Another risk with volunteers who want to show off for others is that they may focus more on personal recognition than a desire to help the community or the environment. This distraction can lead to low motivation and trouble with retention. However, these volunteers can also be hardworking if they channel their desire for recognition into action. Thus, managers should make sure that the volunteers feel their efforts are noticed (Cloyd, 2004). One of the most effective ways to retain these volunteers is to make them feel publicly recognized (Walk et al., 2019). A social media post with a photo of the volunteer on the job, an article in a local newspaper mentioning their name, or an awards ceremony can help volunteers feel appreciated (Hager & Brudney, 2015). These activities help all volunteers feel valued, especially those who want to impress others. Volunteer managers should keep their audience in mind when selecting a method of volunteer recognition. Figure 2 lists recognition tools and for whom they would be the most effective.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Motivation 5: “Me over we.”

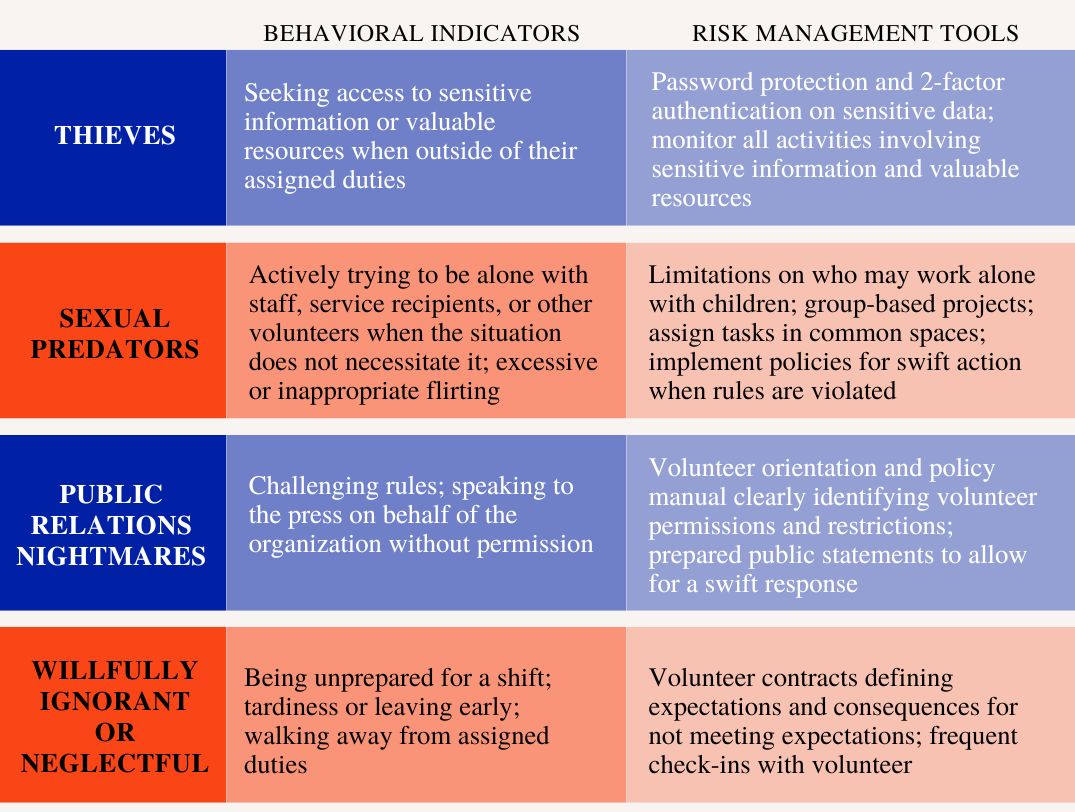

Certain volunteers choose to volunteer with both self-interest and malicious intent (e.g., stealing donor money). A similar risk comes from volunteers who willfully neglect their duties, such as a volunteer assigned to provide an environmental education seminar at a local school who does not arrive prepared to teach. Catching these volunteers before they cause harm is essential. While these volunteers are cause for concern, they are uncommon. Approximately 55% of volunteer managers have expressed concern about risks related to staff and volunteers, but over 90% see it as either unlikely or merely possible that volunteers would damage the organization’s reputation (Domanski, 2016).

Managing Risky Volunteers

While volunteers with ill intentions are relatively rare, just one could cause a great amount of damage (Domanski, 2016). Organizations could face legal liability for the actions of their volunteers in much the same way as they would for actions of their employees (Herman & Chopko, 2014). Those that rely on volunteers should develop official policies for volunteer requirements, screening, and training (Herman & Chopko, 2014). Without these protocols, one bad actor can cause irrevocable damage to an organization.

Organizations can use background checks to identify and prevent malicious volunteers before they start working. However, background checks are not always an option for smaller organizations (Herman & Chopko, 2014), and these checks only capture documented cases of damaging behavior. If managers are unsure about a volunteer’s motives, they can address such concerns by limiting volunteer assignments that are sensitive in nature or related to finances and fundraising. Instead, volunteer managers can assign these potentially risky volunteers to short-term projects with simple, low-stakes tasks, such as picking up litter on a trail (Forsyth, 1999). Finally, it is important to reevaluate the program regularly in order to update volunteer training and/or risk management techniques as needed (Graff, 2012). Figure 3 provides behavioral indicators and management resources for four types of risky volunteers.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Conclusion

The motivation to volunteer can come in many different forms. Some individuals may not fall neatly into one category but instead may express views that align with two or three motivations (Clary & Snyder, 1999). As a result, organizations can combine multiple strategies and tools to manage their volunteers. Understanding a volunteer's motivations can create a better experience for both the volunteer and the organization. The volunteer manager will be able to find the right volunteer for the task and the right task for the volunteer. Organizations can have a more significant impact by meeting everyone’s unique needs, and volunteers can feel more fulfilled.

References

Bang, H., Ross, S., & Reio, T. G. (2013). From Motivation to Organizational Commitment of Volunteers in Non-Profit Sport Organizations. The Journal of Management Development, 32(1), 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711311287044

Clary, E. G., & Snyder, M. (1999). The Motivations to Volunteer: Theoretical and Practical Considerations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8(5), 156–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00037

Cloyd, M. (2017). When Volunteering Is Mandatory: A Call for Research about Service Learning. Multicultural Education, 24(3/4), 36–40.

Domanski, J. (2016). Risk Categories and Risk Management Processes in Nonprofit Organizations. Foundations of Management, 8(1), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1515/fman-2016-0018

Forsyth, J. (1999). Volunteer Management Strategies: Balancing Risk and Reward. Nonprofit World, 17(3), 40–43.

Gabbey, A. E. (2019). Make group volunteering a fun experience. The Volunteer Management Report, 24(4), 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1002/vmr.31133

Graff, L. L. (2011). Risk Management in Volunteer Involvement. In T. D. Connors (Ed.), The Volunteer Management Handbook (pp. 323–360). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118386194.ch14

Hager, M. A., & Brudney, J. L. (2015). In Search of Strategy. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 25(3), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21123

Herman, M. L., & Chopko, M. E. (2014). Exposed: A Legal Field Guide for Nonprofit Executives. 2nd Edition. Nonprofit Risk Management Center.

Mackay, S. A., White, K. M., & Obst, P. L. (2016). Sign and Share: What Influences Our Participation in Online Microvolunteering. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(4), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0282

NCCS Project Team. (2020). The Nonprofit Sector in Brief 2019. Retrieved February 14, 2023, from https://nccs.urban.org/nccs/resources/sector-in-brief-dashboard/

Nichols, G., Hogg, E., Knight, C., & Storr, R. (2019). Selling volunteering or developing volunteers? Approaches to promoting sports volunteering. Voluntary Sector Review, 10(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1332/204080519X15478200125132

Patrick, R., Henderson-Wilson, C., & Ebden, M. (2022). Exploring the Co-Benefits of Environmental Volunteering for Human and Planetary Health Promotion. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 33(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpja.460

Shachar, I. Y., von Essen, J., & Hustinx, L. (2019). Opening Up the “Black Box” of “Volunteering”: On Hybridization and Purification in Volunteering Research and Promotion. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 41(3), 245–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2019.1621660

Tschirhart, M., & Bielefeld, W. (2012). Managing Nonprofit Organizations. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119051626

Walk, M., Zhang, R., & Littlepage, L. (2019). “Don’t you want to stay?” The impact of training and recognition as human resource practices on volunteer turnover. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 29(4), 509–527. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21344

Wearing, S. (2004). Examining Best Practices in Volunteer Tourism. In M. Graham & R. A. Stebbins (Eds.), Volunteering as Leisure/Leisure as Volunteering: An International Assessment (pp. 209–224). CABI Pub. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851997506.0209

Wiley, K., & Evans, M. (2022). Portrayals of Volunteering on U.S. Television: A Textual Analysis. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 51(4), 878–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640211033907

Wiley, K., Thomas, M. B., & Skollar, T. (2022). The Paradox of Compulsory Volunteering: A Textual Analysis of Charity as Punishment on U.S. Television. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 28(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2022.2094150