Organizational leaders face competing priorities when making decisions that steer the focus and resources of their organization. Choosing one pathway over another requires consideration of the organization’s needs and capacities. We present four nonprofit leadership priorities central to organizational decision-making: innovativeness, staff-centered focus, strategy, and systems focus (Cameron et al., 2006). These four priorities are present in for-profit, nonprofit, and governmental organizations. Here, we apply the framework to nonprofit organizations. This publication defines the four priorities and explores their relationships. Finally, leaders will be provided tools for balancing these priorities and the associated strengths during decision-making to effectively fulfill their goals.

Defining Priorities

An organization creates value by achieving its self-determined goals. For nonprofits, value creation equals mission fulfillment. For example, a nonprofit with an environmental conservation mission may define value as reducing carbon emissions or protecting fragile ecosystems from commercial development. A youth empowerment program might define value by the quality of an educational experience, the knowledge gained, and a student’s preparation for the future.

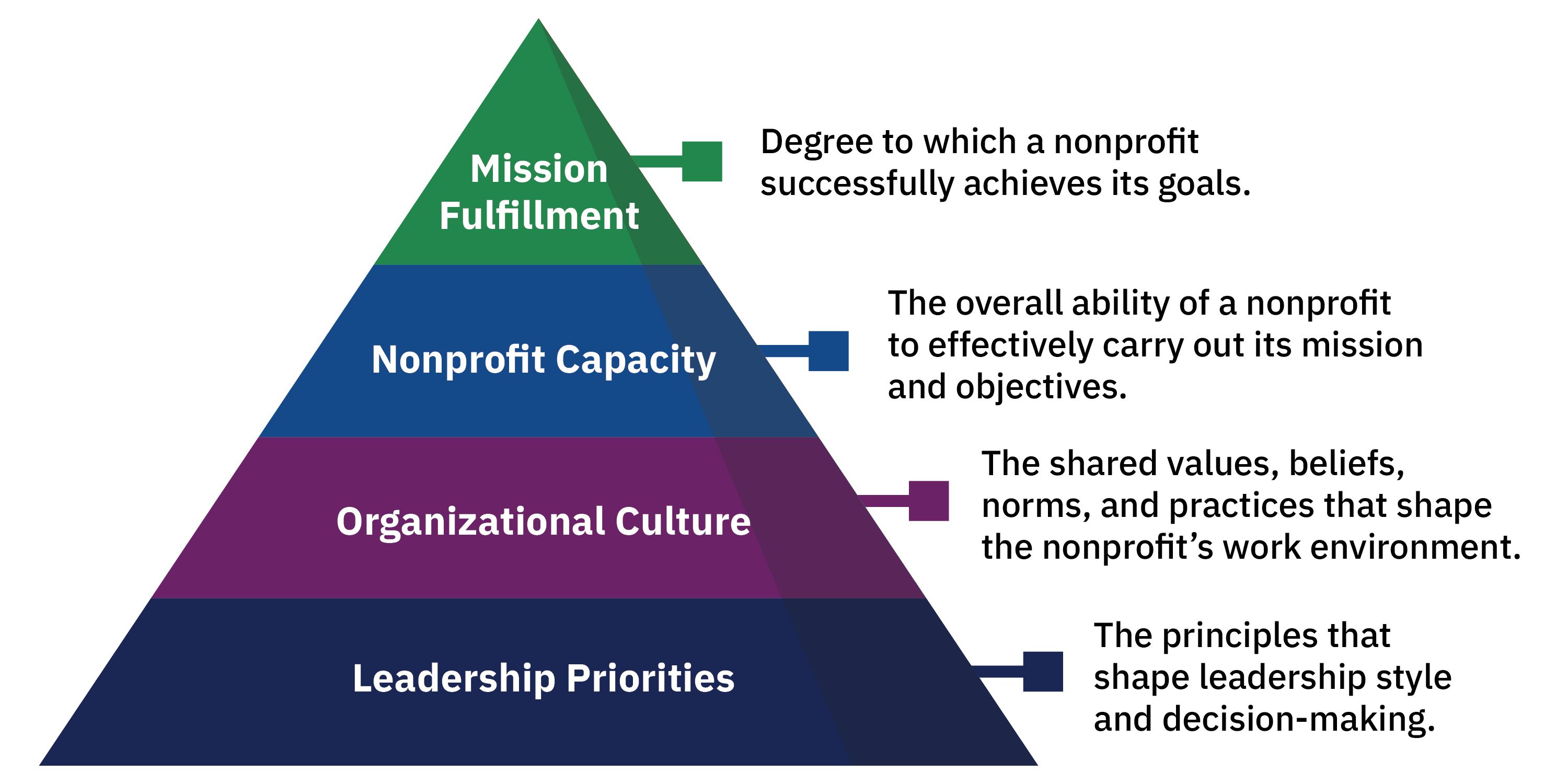

Mission fulfillment guides every activity in a nonprofit. Value is found in creating outputs, such as new products, services, or programs. Value may also be extracted when reforming existing practices or processes to increase efficiency or employee satisfaction. Organizational culture and nonprofit capacity bridge the gap between management priorities and mission fulfillment. Figure 1 (shown at the bottom of p. 2) presents this pathway.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Figure 2 (shown at the bottom of p. 3) visually represents competing concerns on how organizations invest their resources toward mission fulfillment. There is not one concern that is perpetually most important. Instead, these contradictory needs must be considered simultaneously to fulfill a nonprofit’s mission.

Credit: UF/IFAS, adapted from Cameron, K.S. (2014) Competing values leadership (pg. 109-100).

The vertical axis represents a tension between organizational flexibility and stability. An organization focused on adaptability will quickly change to pursue its goals, adapt and integrate new technologies, or hire employees to bring in new ideas. A leader who runs a flexible organization will be viewed as successful in adapting to shifting trends. On the other hand, an organization focused on consistency values predictability and routine. Such an organization sets consistent programmatic timeliness and reporting practices to maintain workplace culture. A leader who successfully runs a stable organization ensures a controlled environment where employees and volunteers know what to expect and what is expected from them. Effective leaders balance these competing needs.

The horizontal axis represents the tension between maintaining internal systems and processes for internal stakeholders (e.g., employees, volunteers, current program participants) versus external positioning relative to other stakeholders (e.g., potential funders, local officials, target program participants). An organization focused on internal maintenance prioritizes existing elements within the organization. This may mean streamlining a planning or production process, maintaining human capacity, or reallocating funding from one project to another. An organization focused on external positioning prioritizes elements it can gain to grow and extend its mission. This may mean restructuring processes to better match the needs of the target population, recruiting new talent, or finding new sources of funding to pursue new or current projects. Strong nonprofits balance this tension point.

Organizational Culture

This framework visually organizes the leadership priorities and nonprofit capacities into four quadrants: innovation, strategic, systems-focused, and staff-centered.

Quadrant 1: Innovative

An innovative manager is creative and forward-thinking. They are change-oriented and help organizations adapt by experimenting with new ideas. Innovation promotes transformation and growth that can help a nonprofit be resilient (Searing et al., 2021). A culture of innovation upholds the nonprofit’s mission while emphasizing new ideas, flexibility, and adaptability. The innovativeness quadrant’s limitation is that it creates a chaotic environment when constant change overshadows stability.

Quadrant 2: Strategic

A strategic manager emphasizes the organization's goals and performance. Nonprofits must focus on effectively planning, implementing, and supporting programs that align with their mission and goals. These priorities allow organizations to adapt strategically to challenges by enhancing resources, capacities, and processes. A culture of strategy adheres to the mission while effectively managing risk through mitigation strategies. A limitation of a strategic focus is overemphasizing conflict avoidance and neglecting the flexibility necessitated by their staff’s day-to-day needs.

Quadrant 3: Systems-Focused

Systems-focused leaders are methodical yet practical. A systems-focused culture installs efficient processes and enforces compliance. Nonprofits require systems-focused capacity when ensuring compliance with regulatory and professional standards. Coordination and monitoring ensure the predictability and productivity of systems within the organization. Leaders build predictability and productivity through optimizing processes, cutting costs, and establishing policies and procedures. A systems-focused capacity can become limited when micromanagement leads to bureaucratic dysfunction and organizational stagnation.

Quadrant 4: Staff-Centered

The staff-centered manager facilitates cooperation and collaboration among employees and volunteers. A staff-centered culture fosters a sense of community through shared values and communication. The focus is involvement and long-term commitment to strengthen the employee and volunteer base. Staff-centered leadership builds up the organization by encouraging bonding and commitment to establish a strong image for the nonprofit. Other nonprofits may be considered partners in an extended community. Limitations of staff-centered leadership can be permissiveness or a lax environment where mission-oriented goals are underemphasized.

Leaders create value by applying this framework. This framework does not explicitly tell leaders how to create value. However, the framework organizes the priorities of the four organizational cultures. It provides guidelines for navigating organizational team culture in varying directions. The framework ties leadership priority, organizational culture, nonprofit capacity, and mission fulfillment, as presented in Figure 1.

Nonprofit Capacity and Competing Priorities

Competing priorities exist in every organization, and it may seem that allocating resources to create value in one quadrant would detract from creating value in another quadrant. For example, a manager who prioritizes strategic capacity may view the diagonal quadrant of a staff-centered capacity as a weakening value. The same logic applies to the systems focus and innovative capacity quadrants. While tensions may arise from this perceived inefficiency, the reality is that nonprofit leaders will need to pursue priorities in all four quadrants as their organization matures. A nonprofit will rarely favor all four quadrants equally, and the emphasis on the importance of each quadrant will continually evolve. Consider these two scenarios where priorities compete.

Scenario 1: Innovation vs. Systems Management in a Community Food Bank

A community food bank manager was exploring new sources for food donations. An urban farm offered to partner with the food bank to donate more culturally appropriate fresh foods for the food bank’s clientele. The food bank’s innovative thinker eagerly pursued the opportunity, recognizing emerging demands from external stakeholders. However, this innovative thinker overlooked the burden new donation sources would impose on the nonprofit’s existing resources (e.g., limited refrigerated storage and dated inventory systems). At the same time, the systems thinker prioritized the needs of current food storage and tracking systems and overlooked the evolving needs of the local community (e.g., a new immigrant community and an aging population).

What Should the Food Bank Manager Do?

The food bank manager should engage their innovative and systems-focused capacities at the correct times, applying innovative capacity in the early stages of growth to incorporate new foods. Then, as the program strengthens, the food bank manager could apply systems-focused capacity to integrate these ideas with existing storage and tracking systems. This manager needed to take advantage of emerging resources while adapting the nonprofit’s existing systems for the future.

Scenario 2: Strategic Capacity vs. Staff-Centered Capacity

A local farming initiative wanted to contribute to a local charter school. Thinking strategically, a manager identified food loss or waste sources, such as misshapen produce, that could be recovered and redirected to the charter school, and proposed a new distribution plan. However, a second manager who prioritized the needs of the initiative’s current farmers and volunteers paused to consider their collective skills, production capacity, and availability and determined they were already working at full capacity. Leveraging strategic capacity alone could prove unproductive for the initiative if a greater emphasis is placed on the newest project while neglecting the nonprofit’s current initiatives. However, centering existing human capacity could limit the initiative’s room for growth.

What Should the Leadership Team Do?

The two leaders should pair strategic and staff-centered thinking to launch the new program by recruiting and allocating new volunteers to the new program. This partnership of capacities will allow the local farming initiative to grow its volunteer base and to deliberately and equally emphasize all initiatives.

The four organizational capacities have advantages and drawbacks that can affect fulfillment of a nonprofit’s mission. These capacities must interact harmoniously to find tradeoffs between the competing priorities. As a nonprofit develops, emphasis on one capacity can rebound towards a neutral or opposite capacity based on immediate needs. When applying this framework to pursue mission fulfillment, a manager should not view the quadrants as “either/or” but rather as “both/and” (Cameron et al., 2006).

Mission Fulfillment Through Finding Balance

Imbalance in organizational priorities can negatively affect a nonprofit. For example, if a team of employees feels that the nonprofit has drifted too far into strategy focus, they may feel the tension pulling away from the culture of staff-centeredness. Employees who do not feel a sense of belonging or teamwork at an organization may choose to leave to pursue another position. On the other hand, if an organizational culture focuses excessively on staff-centeredness by valuing employee commitment above merit and contribution to the mission, the nonprofit may lose its competitive advantage to securing funding. Instability or low revenue may result in employee layoffs or competitors luring employees away (Young et al., 2024).

Leadership must identify priorities, build a healthy organizational culture, and strengthen the nonprofit’s capacity. To do so, leaders should balance an organization’s weaknesses as well. When a manager recognizes an area for improvement, they must change their tactics. Each of the following “levers of change” may help to develop an organization's or team's culture toward the target quadrant (Cameron & Quinn, 2011).

Promoting Innovative Capacity

Establish an innovative environment. Three strategies for establishing an innovative environment are transformational leadership, targeted staff recruitment, and encouragement to experiment. A leader’s innovative capacity is characterized by overcoming challenges using strategies such as persuasion, accommodation, resolution of logistical problems, and clear vision. Modifying technology, championing legislation or regulation change, and providing employee recognition are also effective. Adaptability when overcoming challenges requires leaders to listen to the environment, experiment, and evaluate to see what ideas work. The ability to overcome challenges and work beyond organizational boundaries ensures the success of the innovation.

Promoting Strategic Capacity

Relentlessly pursue the mission. Leaders clearly define the goals, understand the key value drivers, and articulate the targeted strategies. The strategic capacity allows leaders to anticipate problems and respond appropriately. Leaders must start with the end in mind and work backward when developing a program. A program evaluation is needed to ensure the program meets outcomes effectively and to determine what factors drive or hinder that effectiveness. Organizations can also use external support such as consultants, universities, local governments, Extension, and nonprofit partners.

Promoting Systems Management Capacity

Streamline processes. Leaders clearly outline processes for task completion to eliminate errors, waste, or redundancy. Internal capacity involves control, stability, internal focus, and external impact. It involves five components: control environment, risk assessment, control activities, information and communication, and monitoring and evaluation.

Internal control should be a continuous built-in component of operations. Internal control supports the ability to achieve the mission, goals, and objectives. It is essential because it applies to all aspects of a nonprofit’s operations: programmatic, human resources, financial, and compliance. Focusing on systems ensures that financial and performance reports are reliable and that programming complies with applicable laws and regulations.

Promoting Staff Capacity

Empower employees and volunteers. Leaders who allow room for employees and volunteers to act on their own ideas and projects can promote motivation and strengthen team building. Empowerment approaches include promotion of collaboration through goal setting, modeling of positive leadership, and careful advisement. Allowing team members to take ownership of the process while the leader remains available for guidance creates a work culture that supports talent development. Empowering employees and volunteers can be an important asset for nonprofit sustainability and impact.

Developing and managing employees and volunteers involves carefully considering recruiting, hiring, onboarding, performance management, and retaining talent. Nonprofit human capacity relies on five components: succession planning, performance management, volunteer management, talent development, and board development and management. All five components work together to ensure the organization collectively develops its abilities.

Conclusion: The Competing Values Framework for Nonprofits

The Competing Values Framework is a structure to help businesses, nonprofits, or teams foster effective leadership, improve organizational effectiveness, and promote value creation (Cameron & Quinn, 2011). First, the framework can be used to examine how leadership priorities affect the culture and competencies of an organization. Then, it can help articulate how the resulting culture affects value creation. The framework organizes these elements into four different mindsets that nonprofit leaders tend to value and serves as a map to navigate how these mindsets can work together or in contrast with each other to ensure a healthy organization. Applying the framework can change a nonprofit’s culture, leading to productivity, stability, and mission fulfillment.

References

Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2011). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture based on the competing values framework. John Wiley & Sons.

Cameron, K. S., Quinn, R. E., Degraff, J., & Thakor, A. V. (2006). Competing values leadership. Edward Elgar.

Searing, E. A. M., Wiley, K. K., & Young, S. L. (2021). Resiliency tactics during financial crisis: The nonprofit resiliency framework. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 32(2), 480–488. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21478

Young, S. L., Wiley, K. K., & Searing, E. A. (2024). Nonprofit human resources: Crisis impacts and mitigation strategies. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640241251491