Introduction

Calabaza (tropical pumpkin) cultivars are being developed for adoption into the southeastern growing region of the United States, potentially offering growers in this region an additional commercially viable horticultural commodity. In 2023, the value of Cucurbita spp. imported to the United States was $494 million (OEC, n.d.). The culinary varieties of Cucurbita, such as calabaza, have demonstrated a significantly higher gross return than their ornamental cousins. The purpose of this publication is to highlight best harvest, handling, and storage practices to serve growers interested in producing calabaza based on a review of preexisting and pertinent literature. This guidance also draws upon published information on closely related winter squash varieties, like butternut squash, due to the limited available literature on calabaza. The intended audiences of this publication are growers interested in incorporating calabaza into their rotation of crops, Extension agents charged with guiding growers on the harvesting and handling of crops such as calabaza, and anyone who is interested in ethnic vegetable production.

Nomenclature

Belonging to the same species as the familiar butternut squash, calabaza is a variety of Cucurbita moschata species of the family Cucurbitaceae. Common English names for other cucurbit fruits classified as C. moschata include Tahitian squash, West Indian pumpkin, Seminole pumpkin, large cheese pumpkin, Long Island cheese pumpkin, Kentucky field pumpkin, and Tennessee sweet potato (ITIS 2022). The name “calabaza” is popular in Puerto Rico and Latin south Florida when referring to tropical pumpkin. It is also referred to as auyama in the Dominican Republic, ayote in Central America, and zapallo in South America (Maynard et al. 2002).

Growing Conditions

Seeds of winter squash, similar to calabaza, can be sown directly when the soil temperature at the depth of planting reaches 60°F (15.6°C). They take approximately 85–120 frost-free days following planting to reach maturity depending on the variety and location-specific extrinsic factors, such as rainfall and temperature (Bachmann and Adam 2010; Leap et al. 2017). In Florida, calabaza takes approximately three months from seeding to reach maturity (Stephens 2015). Cucurbita moschata squash and pumpkins, including calabaza, rely on cross-pollination to produce fruit (Figure 1), in contrast to crops that self-pollinate, like tomatoes and other nightshade family vegetables (Stephens 2015). Calabaza is highly susceptible to chilling injury during cold nights; therefore, the southeastern growing region of the United States may be ideal because of longer growing seasons and higher crop yield.

Credit: Megan E. Kinsman

Quality Parameters

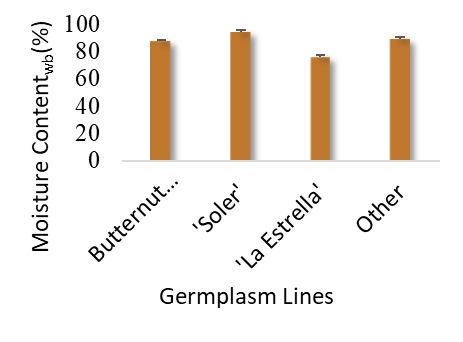

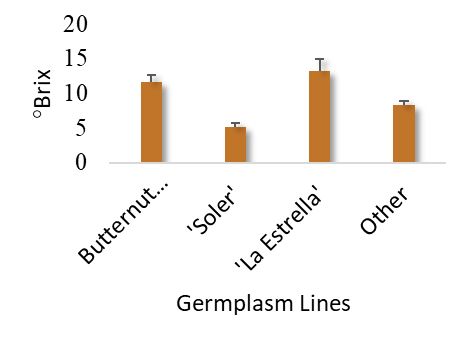

The United States Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (2008) data suggest that culinary varieties of pumpkin, like calabaza, had 30% greater gross financial returns than ornamental pumpkin varieties (Bachmann and Adam 2010). Culinary C. moschata, including calabaza, are characterized by fine-grain flesh and superior flavor (Bachmann and Adam 2010). The sugar-to-starch ratio of the fruit contributes to its taste and texture and is an important consideration for sensory acceptance. Though high-yielding fresh weight varieties may achieve greater marketability and visual acceptability, they may also compromise these important sensory characteristics. Often high-yielding fresh weight is inversely proportional to consumer palatability because starches and sugars are displaced by water and taste and texture are diminished (Loy 2004). Relative sugar content, measured in total soluble solids content (°Brix) should be greater than or equal to 11% to satisfy U.S.-based consumer acceptability (Loy, n.d.). Research shows that average moisture and soluble solids content of butternut squash, two commercial calabaza cultivars (‘Soler’ and ‘La Estrella’), and other calabaza germplasm lines currently being developed range from 76%–94% and 5°Brix–13°Brix, respectively (Kinsman 2023; Figures 2 and 3).

Credit: UF/IFAS

Credit: UF/IFAS

Food retailers and their customers often desire consistently-sized calabaza fruit, weighing approximately 8.8–11 lb (4–5 kg) with deeply orange-colored thick flesh (Maynard et al. 2002). This color is associated with high concentrations of provitamin A carotenoid, β-carotene. Research supports that provitamin A, vitamin C, and phenolic compounds are present in calabaza in varying concentrations (Kinsman 2023; Figure 4). These valuable bioactive compounds promote human health by supporting various functions in the body and acting as antioxidants.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Calabaza should be well matured or fairly well matured (U.S. Grade No. 1 and No. 2, respectively) and free from most, if not all, superficial damage and rot or deterioration (USDA-AMS, n.d.). For more information, visit the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service website on the grading scale and standards for winter squash and pumpkin. Additionally, calabaza flesh is well-suited for several types of processing, such as canning, freezing, blending into puree, and adding to stockfeed/pet food (Loy 2004; Bachmann and Adam 2010).

Harvest

Maturity Indices

Harvest at proper maturity is critical to ensure the highest edible quality. The development of a deep orange or yellow ground spot can be used as a harvest index for calabaza, denoting the appropriate time at which the fruit should be cut from the vine and removed from the field (Loy, n.d.). Fully matured, buff-colored calabaza fruit should have a less lustrous rind that is no longer tinged with green, as depicted in Figure 5 (Leap et al. 2017; Bachmann and Adam 2010). Please note that not all calabaza are buff-colored at maturity; some varieties have a green rind when fully mature, as shown in Figure 6. Calabaza that is harvested prematurely may decrease in palatability and consumer acceptance as the immature seeds continue to utilize nutrients stored within the flesh. Such is the case when butternut squash and other Cucurbita species are harvested too soon (Burrows 2018; Loy 2004; Higgins and Hazzard 2022).

Credit: Megan Kinsman

Credit: Megan Kinsman

Another index that can be used to mark the appropriate time to harvest calabaza is the phenomenon known as stem corking (Figure 7), in which the stem of the fruit dries to brown and begins shrinking away from the vine. Stem corking indicates that the calabaza fruit is no longer receiving significant amounts of nutrients from the mother plant and, soon after, the vines themselves will die (Burrows 2018; Bachmann and Adam 2010). A thumbnail prick into the skin of calabaza fruit can also be used as a harvest index; mature calabaza should produce rinds that are difficult to puncture. However, a thumbnail prick is injurious to the skin of the fruit. Mechanical injuries to the fruit, such as punctures, cuts, abrasions, and bruises, will render the fruit more vulnerable to microbial contamination, increased senescence at the site of the injury, and expedited deterioration (FAO 1989).

Credit: Photo was used with permission from the University of California Postharvest Technology Center (UC-ANR, n.d.). https://postharvest.ucdavis.edu

Harvest Methodology

Harvest calabaza by hand using clean clippers (Leap et al. 2017). To prevent contamination and decay of the fruit, avoid breaking the stem off at the point of attachment. Instead, leave a short stem intact after clipping calabaza from the vine. Move freshly harvested calabaza out of direct sunlight and under shade and/or quickly transport to a packing facility. The exception is when sun-curing (see the following section, Curing). It is important to minimize mechanical injury to the fruit during harvest and handling. Mechanical damage expedites senescence (deterioration due to aging) and ripening of the calabaza fruit. These injuries can also provide infection sites for microbial contaminants, potentiating premature decay and losses from rot (FAO 1989; Sargent et al. 2007).

Storage Guidelines

Curing (Optional)

Curing mitigates quality losses to extend the shelf life of whole, intact calabaza during long-term storage. Undamaged and unblemished calabaza can be cured at 80°F–85°F (26.7°C–29.4°C) with 80%–85% relative humidity for 5–10 days (Bachmann and Adam 2010; Goossen, n.d.). The curing process causes a slight moisture loss in calabaza, thereby increasing the dry weight of the fruit, concentrating sugars within the edible flesh portions, hardening the protective outer skin, and slowing the rate of cellular respiration and ripening (Leap et al. 2017).

Calabaza can also be sun-cured. Immediately following harvest, the calabaza can be placed in a long, narrow row under direct sunlight for one to two weeks (Leap et al. 2017). Weather conditions should be monitored; outside temperatures should not exceed 95°F (35°C); and calabaza should be collected from the field if inclement weather conditions are forecasted (e.g., rain, heat wave). Sun-curing calabaza should not exceed two weeks to avoid heat injury to the fruit or an increase in susceptibility to pest damage (Leap et al. 2017).

Packing, Cooling, and Storage

After harvest or curing, cull calabaza to remove damaged and diseased fruit. Clean, dry, and grade the acceptable fruit before handling further. Calabaza can be bulk-packed in clean, corrugated fiberboard or plastic bins or packed in corrugated cartons or plastic lugs and palletized (Maynard and Hochmuth 2007). The fruit can be stored at ambient temperatures for a couple of weeks.

Although calabaza is less perishable than many other fresh commodities and exhibits a relatively low respiration rate, cold storage is still beneficial. Room cooling is the recommended method for removing field heat from recently harvested fruit (Sargent et al. 2007). This cooling method is slow, so it is vitally important that refrigerated air circulation within the room is unobstructed and that produce containers are sufficiently vented to allow maximum airflow during cooling and storage (Sargent et al. 2007). Cooling at 50°F–59°F (10°C–15°C) with a relative humidity of 50%–70% will result in approximately two to three months of storage life (Cantwell 2001; Bachmann and Adam 2010; Watson et al. 2016). Storage with relative humidity below 50% will accelerate dehydration and weight loss in the calabaza, while relative humidity above 70% will encourage fungal and/or bacterial growth and subsequent decay of the fruit (Higgins and Hazzard 2022).

Ethylene Production

Calabaza produces only trace amounts of ethylene—up to 1.0 microliter per kilogram-hour at 68°F (20°C) (Cantwell 2001; Watson et al. 2016). It does, however, have a moderate sensitivity to ethylene and should not be stored with or near climacteric (ethylene-producing) fruits (e.g., apples, bananas, cantaloupe, tomatoes) (Cantwell 2001).

Storage Decay

Fungi are common causal agents of calabaza storage rot that lead to untimely decay. Diseases caused by these deleterious fungi include Fusarium fruit rot (Fusarium spp), black rot (Phoma cucurbitacearum), gray mold (Botrytis cinerea), and white mold (Sclerotinia sclerotiorum) (OSU 2014). Proper harvesting, handling, and storage of calabaza, as outlined in this publication, will mitigate storage rot losses. Additionally, fungicides can be integrated into a pest management plan for growing calabaza. A list of registered fungicides specifically for Cucurbita spp., including calabaza, is updated routinely in Chapter 7 of the Vegetable Production Handbook of Florida, EDIS publication HS725.

References

Bachmann, J., and K. L. Adam. 2010. “Organic Pumpkin and Winter Squash Production.” ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture. National Center for Appropriate Technology. https://attra.ncat.org/publication/organic-pumpkin-and-winter-squash-marketing-and-production/

Burrows, R. 2023. “Harvesting and Storing Pumpkins and Winter Squash.” South Dakota State University Extension. Updated September 7, 2023. https://extension.sdstate.edu/harvesting-and-storing-pumpkins-and-winter-squash

Cantwell, M. 2001. “Properties and Recommended Conditions for the Long-Term Storage of Fresh Fruits and Vegetables.” University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources Postharvest Research and Extension Center. https://postharvest.ucdavis.edu/sites/g/files/dgvnsk12711/files/inline-files/230191.pdf

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 1989. “Perishability and Produce Losses: Post-Harvest Damage to Fresh Produce.” In Prevention of Post-Harvest Food Losses: Fruits, Vegetables and Root Crops. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/4/t0073e/t0073e00.htm

Goossen, C. n.d. “Harvesting Winter Squash for Peak Flavor and Optimal Storage Life.” Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners. Accessed June 11, 2025. https://www.mofga.org/resources/crops/harvesting-winter-squash-for-flavor-and-storage/

Higgins, G., and R. Hazzard. 2022. “Pumpkin & Winter Squash Harvest, Curing, and Storage.” UMass Extension Vegetable Notes 34 (18): 4–6. https://ag.umass.edu/sites/ag.umass.edu/files/newsletters/august_18_2022_vegetable_notes.pdf

Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). 2022. “Cucurbita moschata Duchesne.” Taxonomic Serial No. 22370. Last updated November 15, 2022. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=22370#null

Kinsman M. 2023. “Macronutrients and Bioactive Compounds Present in Calabaza (Tropical Pumpkin) Breeding Lines and Correlations with Mesocarp Color.” Master’s Thesis, University of Florida.

Leap, J., D. Wong, and K. Yogg-Comerchero. 2017. “Organic Winter Squash Production on California’s Central Coast: A Guide for Beginning Specialty Crop Growers.” University of California, Santa Cruz: Center for Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05q047z3

Loy, B. n.d. “Managing Winter Squash for Fruit Quality and Storage.” University of New Hampshire. Accessed June 11, 2025. https://agsci.oregonstate.edu/sites/agscid7/files/horticulture/attachments/Managing%20winter%20sq%20for%20fruit%20quality%20and%20storage%20Loy.pdf

Loy, J. B. 2004. “Morpho-Physiological Aspects of Productivity and Quality in Squash and Pumpkins (Cucurbita spp.).” CRC Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 23 (4): 337–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352680490490733

Maynard, D. N., G. W. Elmstrom, S. T. Talcott, and B. R. Carle. 2002. “‘El Dorado’ and ‘La Estrella’: Compact Plant Tropical Pumpkin Hybrids.” HortScience 37 (5): 831–833. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.37.5.831

Maynard, D. N., and G. J. Hochmuth. 2007. Knott’s Handbook for Vegetable Growers. 5th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470121474

Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC). n.d. “Vegetables: Pumpkins, Squash and Gourds (Cucurbita spp.), Fresh or Chilled.” Retrieved March 23, 2025. https://oec.world/en/profile/hs/vegetables-pumpkins-squash-and-gourds-cucurbita-spp-fresh-or-chilled?yearSelector1=2023

Oregon State University (OSU). 2014. “Winter Squash Storage Rots and Their Management.” Oregon Vegetables. https://agsci.oregonstate.edu/oregon-vegetables/winter-squash-storage-rots-and-their-management

Sargent, S. A., M. A. Ritenour, J. K. Brecht, and J. A. Bartz. 2007. “Handling, Cooling and Sanitation Techniques for Maintaining Postharvest Quality.” HS719. University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Archived from https://ufdc.ufl.edu/IR00001676/00001/pdf

Stephens, J. M. 2015. “Calabaza—Cucurbita moschata Duch. ex Lam.” HS572. University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Archived from https://www.growables.org/informationVeg/documents/Calabaza.pdf

University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources (UC-ANR). n.d. “Pumpkin & Winter Squash.” Postharvest Research and Education Center. Accessed December 17, 2024. https://postharvest.ucdavis.edu/produce-facts-sheets/pumpkin-winter-squash

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service (USDA-AMS). n.d. “Fall and Winter Type Squash and Pumpkin Grades and Standards.” Accessed November 15, 2022. https://www.ams.usda.gov/grades-standards/fall-and-winter-type-squash-and-pumpkin-grades-and-standards

Watson, J. A., D. Treadwell, S. A. Sargent, J. K. Brecht, and W. Pelletier. 2016. “Postharvest Storage, Packing and Handling of Specialty Crops: A Guide for Florida Small Farm Producers: HS1270, 10/2015.” EDIS 2016 (1). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-hs1270-2015