Introduction

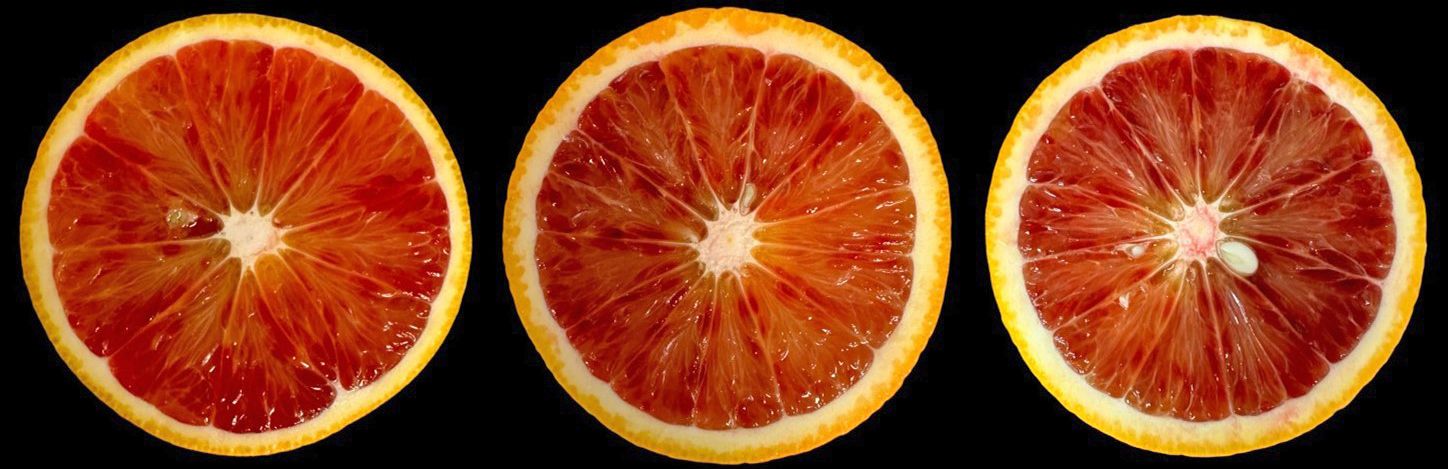

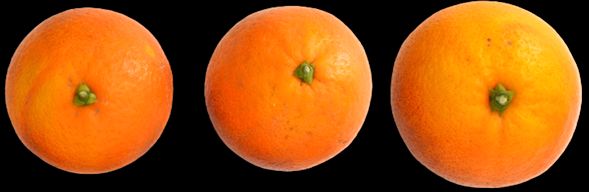

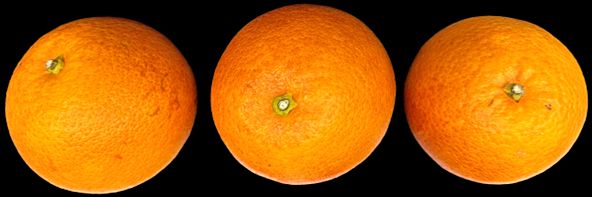

Blood oranges (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck) are a type of citrus fruit (Figure 1) that is characterized by the red color of the fruit flesh resulting from the presence of anthocyanins (Figure 2), a group of pigments known for their antioxidant and health-promoting properties. Blood oranges are highly appreciated by consumers for their flavor, nutritional quality, and visual appeal. However, the fruit are susceptible to physiological disorders that can occur after harvest. Postharvest physiological disorders are defined as disorders that occur in plant organs after harvest, resulting in abnormal changes in their physiology, biochemistry, and morphology. In blood oranges, postharvest physiological disorders can affect fruit appearance, quality, taste, nutritional value, shelf life, and marketability. Therefore, understanding these postharvest physiological disorders is crucial for growers, distributors, and consumers alike to ensure high quality and long postharvest life of blood oranges. By understanding the factors contributing to these disorders and applying appropriate management strategies, growers and distributors can maintain the quality and nutritional value of blood oranges while minimizing economic losses. In this publication, we discuss the main postharvest physiological disorders of blood oranges, their causes, symptoms, and effects on quality, and the current and potential methods to prevent or reduce them. This will further enhance our ability to prevent and mitigate these disorders, ultimately benefiting the citrus industry and consumers worldwide.

This publication aims to provide valuable information on the major postharvest physiological disorders affecting blood oranges, including their causes, symptoms, and practical strategies for prevention and control. The target audience includes citrus growers, harvest and packinghouse personnel, Extension agents, and specialists who seek to minimize postharvest losses and maintain high fruit quality. By improving awareness of these disorders and their management, this publication aims to support more effective postharvest handling and storage practices of blood oranges.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Postharvest Physiological Disorders

Postharvest physiological disorders pose significant challenges for blood oranges, resulting in a range of abnormal non-pathological changes that affect fruit quality, shelf life, and marketability. These deviations can have detrimental effects on both the external appearance and internal composition, potentially compromising their appeal and commercial viability from storage to market. The following are common postharvest physiological disorders of blood orange fruit that may develop during postharvest cold storage.

Chilling Injury

Blood oranges, like other citrus fruit, are susceptible to chilling injury (CI) during storage and transportation. This is a natural problem that happens when the fruit is kept at temperatures that are too low (i.e., below critical storage temperatures). It can seriously affect the fruit’s quality and appearance, making it harder to sell and disappointing for buyers. These low temperatures cause physiological damage, but do not freeze the fruit. Typically, CI starts when the fruit is stored at temperatures below 5°C (41°F). The symptoms may not show up right away and often become visible after the fruit is taken out of cold storage. Proper storage of blood oranges can also help reduce the occurrence of CI by keeping the fruit at a cool temperature, but not lower than 6°C (42.8°F), to avoid chilling and to thereby preserve their quality. Keeping blood oranges at this safe temperature helps protect their freshness and reduces the risk of chilling injury. The symptoms of CI in blood oranges include: external peel pitting affecting the flavedo (the orange-colored outer part of the peel), which can occur as small, round depressions or larger, shallower sunken areas; browning of the albedo (the underlying white part of the peel); peel water soaking; and diffuse sunken areas in the flavedo (Figure 3). These signs make the fruit look damaged and can lower its taste and nutrition. The amount of damage that occurs depends on the type of orange, the extent of ripeness at harvest (less ripe fruit are more likely to get CI), the duration of exposure to cold, and the temperature. Many aspects of blood orange CI are similar to CI in grapefruit, details of which can be found in Ask IFAS publication HS935, “Chilling Injury of Grapefruit and Its Control.”

Genetic factors also affect how sensitive different blood orange cultivars are to CI. The differences in postharvest CI and susceptibility to cold stress among blood orange cultivars can be attributed to physiological and biochemical responses to cold storage conditions. For example, in our tests, ‘Moro’ and ‘Tarocco’ exhibited significantly more severe CI symptoms than ‘Sanguinello’ when stored at 2°C (35.6°F). ‘Sanguinello’ may be more tolerant of CI compared to ‘Moro’ and ‘Tarocco’ due to higher activity of antioxidant system enzymes, unsaturated fatty acids, less severe electrolyte leakage, and lower levels of malondialdehyde and hydrogen peroxide. These characteristics working in conjunction could prevent the loss of membrane integrity and alleviate CI symptoms. Therefore, these differences highlight the importance of genetic and biochemical diversity among cultivars, influencing their tolerance to chilling temperatures and their overall postharvest quality. Understanding these variations can aid in selecting the appropriate storage conditions for different cultivars to minimize CI and to maintain optimal fruit quality.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Oleocellosis

Oleocellosis, also known as oil spotting, is a physiological disorder that can occur during the preharvest period or postharvest storage. Oleocellosis results in the collapse of oil cells and the release of their contents (Figure 4). The oils that are released from the oil glands are phytotoxic to surrounding cells, and their release results in visible pitted or burned spots on the flavedo. The main mechanisms of oleocellosis in blood orange fruit involve the rupture of oil glands due to impacts during picking, rough handling, or falling, leading to oil release and cell damage. High turgidity of the oil cells is associated with easier breakage. This means that fruit harvesting and postharvest handling may need to be delayed following irrigation events and rainy conditions.

The transfer of oil from a damaged fruit’s surface to an adjacent fruit during postharvest handling can result in more severe lesions, affecting a larger area and causing damage to epidermal and cortex cells in the flavedo. In addition to negatively impacting the appearance of fruit in the marketplace, damage to the peel from released oil can lead to increased decay.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Stem-End Rind Breakdown

Stem-end rind breakdown (SERB) is a senescence-related (i.e., aging-related) postharvest physiological disorder that affects blood orange fruit. It is characterized by the collapse of peel tissue (“rind”) around the stem end of the fruit, resulting in an area that becomes dark and sunken (Figure 5). Stem-end rind breakdown usually develops after harvest and during storage, often within 2 to 7 days after packing, is promoted by relative humidity levels of less than 90% and relatively warm temperatures during degreening and leads to water loss. Fruit affected by SERB are also more susceptible to decay. Preharvest conditions can impact the susceptibility of fruit to SERB, with reports suggesting that fruit from water-stressed trees or those with nutritional imbalances involving nitrogen and potassium may be predisposed to the disorder. For more information on SERB, see Ask IFAS publication HS936, “Stem-End Rind Breakdown of Citrus Fruit.”

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Calyx Senescence

Postharvest calyx senescence in blood oranges refers to the aging process and deterioration of the calyx—the green part at the stem end of the fruit where it was attached to the tree (Figure 6)—due to chlorophyll pigment degradation (Figure 7). The process of calyx senescence can lead to browning and abscission (shedding) of the calyx (Figures 8 and 9). While the symptoms of calyx senescence are only superficial, they can affect the appearance and consumer acceptability of citrus fruit. Factors influencing calyx senescence include ethylene exposure, higher storage temperatures, and prolonged storage durations. Minimizing the use and duration of postharvest degreening treatments with ethylene, quickly cooling blood oranges (within 24 hours of harvest) to their lowest safe temperature of 6°C (42.8°F), and providing a proper relative humidity of 90%–95% slow the development of calyx senescence. Note that relative humidity greater than 95% should be avoided because it may result in water condensation that can promote decay development.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

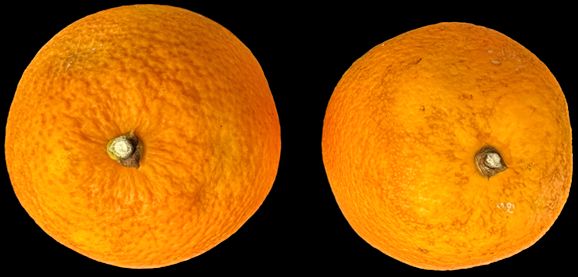

Shriveling

Shriveling in blood orange fruit is considered a postharvest physiological disorder. It is associated with water loss and leads to a wrinkled appearance of the fruit’s peel (Figure 10). This disorder can be exacerbated by factors such as improper storage conditions, particularly low humidity or high storage temperatures, which increase transpiration and water loss from the fruit. As stated earlier, blood oranges are best stored at 6°C (42.8°F) with a relative humidity of 90%–95%. Moreover, handling stress and damage experienced during postharvest handling can weaken the fruit's peel, making it more susceptible to shriveling.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

The Methods for Controlling Postharvest Physiological Disorders

Controlling postharvest physiological disorders in blood oranges requires specialized approaches adapted to the unique characteristics of this citrus species. Postharvest CI remains challenging for the citrus industry, particularly for sensitive blood orange cultivars. To mitigate the risk of CI and maximize shelf life, blood oranges should be stored at their optimal temperature, which is typically around 6°C to 10°C (42.8°F to 50°F), or subjected to pre-storage treatments with chemical elicitors to increase the fruit’s chilling tolerance and control fruit senescence. Maintain the relative humidity between 90% and 95% to avoid both shriveling and decay. Minimizing fruit exposure to ethylene during degreening and excluding or removing the ethylene source that was used during the degreening process from storage rooms can delay fruit and calyx senescence and reduce fruit decay. By integrating these methods, the postharvest life of blood oranges can be maximized while preserving fruit quality.

Summary

Effective management of postharvest physiological disorders in blood oranges is critical to preserving fruit quality, minimizing economic losses, and ensuring consumer satisfaction. CI can be reduced by maintaining storage temperatures at 6°C to 10°C (42.8°F to 50°F) and avoiding prolonged exposure to colder conditions. Cultivar-specific strategies are recommended, as some cultivars (e.g., ‘Moro’, ‘Tarocco’) are more sensitive to low temperatures than others (e.g., ‘Sanguinello’). Gentle harvest and handling practices are essential to minimize oleocellosis, particularly during periods of high oil cell turgor following rain or irrigation. To prevent stem-end rind breakdown and shriveling, fruit should be stored at high relative humidity (90%–95%) and carefully managed during degreening to reduce peel dehydration. Minimizing ethylene exposure and promptly cooling fruit to safe storage temperatures can help delay calyx senescence and preserve visual quality. Integrating these practices through proper harvest timing, handling, temperature and humidity management, and cultivar selection can significantly enhance postharvest performance and extend the marketability of blood oranges.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Research Capacity Fund (Hatch) projects, project award no. 7004457, from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

References

Habibi, F., M. E. García-Pastor, F. Guillén, M. Serrano, and D. Valero. 2021. “Fatty Acid Composition in Relation to Chilling Susceptibility of Blood Orange Cultivars at Different Storage Temperatures.” Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 166: 770–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.06.013

Habibi, F., M. E. García-Pastor, J. Puente-Moreno, F. Garrido-Auñón, M. Serrano, and D. Valero. 2023. “Anthocyanin in Blood Oranges: A Review on Postharvest Approaches for Its Enhancement and Preservation.” Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 63(33): 12089–12101. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2022.2098250

Habibi, F., A. Ramezanian, F. Guillén, D. Martínez-Romero, M. Serrano, and D. Valero. 2020. “Susceptibility of Blood Orange Cultivars to Chilling Injury Based on Antioxidant System and Physiological and Biochemical Responses at Different Storage Temperatures.” Foods 9(10): 1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9111609

Habibi, F., A. Ramezanian, F. Guillén, M. Serrano, and D. Valero. 2020. “Blood Oranges Maintain Bioactive Compounds and Nutritional Quality by Postharvest Treatments with γ-aminobutyric Acid, Methyl Jasmonate or Methyl Salicylate during Cold Storage.” Food Chemistry 306: 125634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125634

Lado, J., P. J. R. Cronje, M. J. Rodrigo, and L. Zacarías. 2019. “Citrus.” In Postharvest Physiological Disorders in Fruits and Vegetables, edited by S. T. De Freitas and S. Pareek. 377–398. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b22001-1

Porat, R. 2008. “Degreening of Citrus Fruit.” Tree and Forestry Science and Technology 2(Special Issue 1): 71–76.

Ritenour, M. A., and H. Dou. 2003. “Stem-End Rind Breakdown of Citrus Fruit: HS936/HS193, 7/2003.” EDIS 2003(13). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-hs193-2003

Ritenour, M. A., H. Dou, and G. T. McCollum. 2003. “Chilling Injury of Grapefruit and Its Control: HS935/HS191, 7/2003.” EDIS 2003(13). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-hs191-2003