Purpose and Target Audience

Ectomycorrhizal fungi (EMF) form symbiotic relationships with approximately 60% of trees and woody plants in temperate and boreal forests. EMF also serve as the primary symbionts in subtropical and tropical forests, particularly in conifer forests, including those in Florida's climate. EMF play a pivotal role in the overall functioning of natural and managed forest and woody ecosystems (Anthony et al. 2022; Chen et al. 2017). These fungi influence the global carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycles, sequestering or supplying these elements as necessary for ecosystem processes and resilience. For instance, it is estimated that mycorrhizal fungi collectively regulate around 80% of plant nitrogen and 50% of soil carbon, affecting the economic contribution of numerous tree crops and forest trees (van der Heijden et al. 2015; Hawkins et al. 2023; van der Heijden and Horton 2009). However, EMF are susceptible to environmental stressors and management practices, including fertilizers, fungicides, and mechanical disturbances. This publication aims to provide knowledge to the general public on the biology and ecological functions of EMF in natural and managed forest ecosystems. By understanding the role and benefits of EMF in these environments, forest managers, tree nursery operators, and timber industry stakeholders can gain valuable insights for incorporating EMF into their management practices.

Introduction

Mycorrhizal fungi are a group of fungi that form symbiotic relationships with plant roots. Hidden beneath the soil’s surface, these fungi have a pivotal role in shaping the interplay among plants, soil, and soil biota. Soil biota includes all plant matter below the soil surface, microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, archaea, fungi, algae, viruses), and soil fauna (e.g., protozoa, springtails, spiders, insects, nematodes, earthworms). Mycorrhizal fungi orchestrate the health and functions of ecosystems by forming extensive mycelial networks of branching root-like structures called hyphae that facilitate resource trade, communication between plants and fungi, and transport of nutrients and water. Over 90% of all land plants form symbiotic associations with mycorrhizal fungi (Chen et al. 2017; Baslam et al. 2011; Begum et al. 2019; Zhu et al. 2011). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and ectomycorrhizal fungi (EMF) are the most significant types of mycorrhizal fungi that contribute to nutrient cycling, plant resilience, and biodiversity in terrestrial ecosystems (Hage-Ahmed et al. 2018; Birhane et al. 2012). This publication will focus on the ecological and biological roles of EMF. Find a detailed discussion on the role of AMF in agricultural systems in EDIS publication PP383, “Biology, Ecology, and Benefits of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Agricultural Ecosystems.” Understanding the ecological significance of mycorrhizal associations is crucial for unraveling belowground interactions, and analyzing data provides practical implications for natural and agricultural ecosystems. EMF are prominent in connecting the vast root systems of forests and woodland areas around the world. To fully appreciate the ecological impact of EMF, it is essential to understand their biology and distribution in various ecosystems.

Overview of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi

EMF are the second most prolific type of mycorrhizal fungi after AMF, which differ in their colonization strategies and plant associations (Figueiredo et al. 2021; Johnson et al. 2012). EMF are distributed globally across diverse ecosystems and can be found in tropical, temperate, and boreal forests, as well as colder alpine and arctic regions (Figueiredo et al. 2021; Vincent and Declerck 2021; Kumar and Atri 2017). EMF, commonly found within the phyla Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, form beneficial relationships with approximately 6,000 tree species (Phillips et al. 2013; Corrales et al. 2018; Martin et al. 2016). Ascomycota and Basidiomycota are divisions of fungi that differ in how they produce spores: Ascomycota produce their spores inside sacs, whereas Basidiomycota form spores in specialized, external cells called basidia. These two groups of fungi are important in forest ecosystems due to their ability to modify plant signaling, aid in organic matter decomposition, facilitate nutrient cycling, build soil structure, sequester carbon, and hedge against environmental stressors (Phillips et al. 2013; Herman et al. 2011; Cahanovitc et al. 2022). These interactions all begin below the soil’s surface in the root system.

Biological Interactions Among EMF, Their Plant Hosts, and Soil

Root Colonization

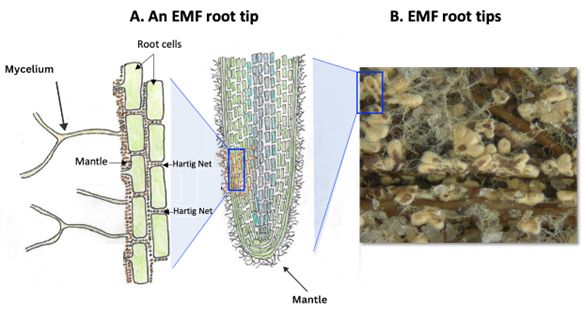

Ectomycorrhizal fungal hyphae, the network of fungal filaments germinated from spores, can detect plant signals and grow toward plant root tips. A portion of the hyphal biomass forms a layer around the root tips, known as the fungal mantle or sheath (Figure 1A; Hock 2012). This mantle protects the root tips from the surrounding soil and facilitates the exchange of plant carbohydrates for other nutrients provided by the fungi (Hock 2012). While most EMF species form a mantle around the root tip, some species do not. Ectomycorrhizal fungal hyphae penetrate the plant root, growing around and between the compact, waxy outer epidermal cells and the larger, thin-walled cortex cells, which contain vacuoles for storage. This internal network of hyphae, called the Hartig net (Figure 1A), facilitates nutrient and energy exchanges (Stuart and Plett 2020).

Credit: (A) Holly Andres and (B) Hui-Ling Liao, UF/IFAS

Soil Nutrient Cycling and Nutrient Exchange

Nutrient cycling is a vital ecological process that circulates essential elements throughout ecosystems, moving between abiotic (physical) environments and biotic (living) organisms. This continuous exchange supports ecosystem stability by ensuring key elements such as carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus remain available for growth and development. Releasing nutrients into the soil is particularly crucial for supporting plant growth and ecosystem function.

Through the Hartig net, EMF facilitate the uptake of nutrients, such as phosphorus and iron; convert organic nitrogen to the forms that plants can use; and may help sequester carbon (Wang et al. 2025). For example, EMF produce extracellular proteinases, specialized enzymes that break down proteins, facilitating the release of organic nitrogen, which then becomes available for uptake (Nygren et al. 2007). This is important as nitrogen is essential in the process of photosynthesis, where sunlight is converted into energy to help the plants grow.

Additionally, EMF can obtain soil phosphorus, particularly in soils with lower levels of inorganic phosphorus (e.g., from the reduced use of phosphorus fertilizers), through their hyphal network (Meeds et al. 2021). Phosphorus is an essential nutrient for early root growth, plant and seed development, and water efficiency. EMF are known to release oxalic acid (an organic acid) into the soil that could solubilize iron-bound phosphorus, aluminum-bound phosphorus, and occluded phosphorus from soil phosphates and dissolve calcium-bound phosphorus in the soil, increasing phosphorus availability and promoting phosphorus mobilization from calcium-rich soils (Lapeyrie et al. 1990; Zhang et al. 2014). EMF also acquire micronutrients, such as zinc and iron, from the soil (Colpaert et al. 2011; Ruytinx et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2023). In return, EMF receive carbon from their hosts (Phillips et al. 2013). These micro-interactions lay the groundwork for EMF to contribute to the broader ecosystem.

The Role of EMF in Tree Growth, Adaptation to Abiotic and Biotic Stresses, and Forest Ecosystem Services

EMF contribute to many forest ecosystem services, which are benefits humans derive from different ecosystems and are categorized into four types: provisioning, cultural, supporting, and regulating services. Not only do they support plant growth through water and nutrient acquisition, but they can also improve soil structure, prevent erosion, promote diversity, and detoxify pollutants such as heavy metals and pesticides (Branco et al. 2022; Policelli et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2021). One ecosystem service that can benefit humans both directly and indirectly is tree growth.

Tree Growth

Building strong symbiotic associations through mycorrhizal symbionts can increase plant biomass, shoot height, root growth, shoot basal diameter, and enzyme activity (Aryal et al. 2021; Sebastiana et al. 2018; Yin et al. 2018). A study by Wang et al. (2021) showed that seedlings inoculated with EMF had better rates of survival, including the local Pinus species in Florida, such as slash pine (Karlsen-Ayala et al. 2022). Although plants exhibited improved growth and function when colonized with EMF, research is still needed to determine whether enhanced plant vigor or EMF function is the primary driver of growth (Aryal et al. 2021). Furthermore, EMF are able to support tree growth, which is important for timber and orchard managers, especially during periods of abiotic stress, such as drought and heavy metal contamination, when trees typically limit their growth.

Drought Stress

EMF colonization is shown to be particularly useful during times of drought stress. Researchers reported that calcium availability is necessary during periods of drought, when there is low soil water availability. EMF promote the uptake of calcium during drought, thus improving water use efficiency (Li et al. 2021). Besides increasing essential nutrients, EMF improve the regulation of biochemicals, such as superoxide dismutase and peroxidase, that help the host plants withstand reduced water conditions (Yin et al. 2021; Alvarez et al. 2009). These chemicals improve tolerance and help maintain plant growth and vigor. Enhanced absorption during drought is beneficial; however, when heavy metals are present, EMF have fascinating mechanisms to help plants overcome such conditions.

Heavy Metal Detoxification

EMF mitigate the adverse effects of heavy metal toxicity in soils, providing a protective shield against the hazards posed by contaminated soils. One of the mechanisms by which EMF may alleviate metal toxicity is through the process of metal immobilization. The fungal mantle around the root tips can act as a sink for metals, such as zinc (Zhang et al. 2021), and regulate their transfer to the root vascular system, which is the central tissue system inside plants that is responsible for transporting water, nutrients, and soil (Ma et. al. 2014). A study by Ma et al. (2014) demonstrated that under conditions of high cadmium concentration, EMF significantly enhanced cadmium uptake. This effect likely resulted from an increase in root surface area, a higher absorption rate, and the overexpression of genes involved in cadmium uptake and transport. Additionally, EMF improved the host plants' tolerance to metals through increased detoxification, better nutrient and carbohydrate status, and enhanced defense preparedness (Colpaert et al. 2011).

Another strategy employed by EMF involves exclusion. By chelating metals both externally and internally, EMF may bind these metals to their fungal walls (Luo et al. 2014). This can be accomplished without hindering nutrient transport (Colpaert et al. 2011). EMF may increase the accumulation of heavy metals in plants (Tang et al. 2019); however, EMF may protect plants by the dilution effect as they continue to draw in water and nutrients (Chot and Reddy 2022). This can be useful for reclaiming contaminated soils since EMF can help remove heavy metals and pollutants from them. Selecting rapidly growing trees, such as the hybrid poplar tree, to host EMF may be a beneficial technique for these phytoremediation efforts (Zalesny et al. 2019).

Furthermore, EMF possess the ability to enhance plant tolerance to heavy metal stress by boosting their antioxidant enzymes and compounds (Wang et al. 2025). Antioxidant activity reduces the reactive oxygen species, which are by-products of normal cell metabolism yet are highly reactive molecules that negatively impact plants (Begum et al. 2019). Reactive oxygen species act as signaling molecules in stress responses and development, but they can cause plant cell damage if present at excessive levels. Improving the abilities of plants to protect against oxidation allows plants to divert resources toward growth and development. However, immobilization, exclusion, and regulation of antioxidant activities are dependent on the specific species of both plant and fungal partners (Colpaert et al. 2011). Therefore, investigating the plant-EMF relationship according to species is important to achieve the best management outcomes.

Ecosystem Services

As highlighted in the previous section, the benefits provided by EMF are substantial. Ecosystem services provided by natural and managed forest systems refer to the direct and indirect benefits offered to humans, including resources like timber, clean water, climate regulation, and recreational activities. These fungi provide multifaceted services in natural and forested settings by improving soil structure, enriching nutrient cycling and absorption, boosting plant resilience and stress tolerance, increasing plant productivity, improving ecosystem diversity, and supporting healthy ecosystems. In addition to supporting plant resilience, EMF improve soil conditions to help plants grow better. Soil conditioning is one of the methods by which EMF benefit forest systems, and it directly promotes plant growth and function.

Soil Structure and Ecosystem Recovery

EMF significantly enhance soil stability and aggregation, which are vital for ecosystem resilience. Their hyphal networks bind soil particles, forming stable aggregates that reduce erosion and improve moisture and nutrient retention, ultimately enhancing soil structure and soil stability (Zheng et al. 2014; Policelli et al. 2020). EMF are especially beneficial in post-disturbance environments, like logged, burned, or damaged forests, where their networks help re-establish soil structure and promote ecosystem function (Franco et al. 2014; Gil-Martinez et al. 2018). In addition to acquiring and retaining nutrients, EMF keep nutrients cycling.

Biogeochemical Cycling

One of the primary services rendered by EMF is the facilitation of nutrient cycling and absorption, particularly of nitrogen, phosphorus, iron, and zinc, which may be limited in soil but are required for plant growth. These fungi extend their hyphal networks, effectively increasing the surface area for nutrient absorption by the plant roots and enhancing biogeochemical cycling by efficiently transferring nutrients between plants, which contribute to the overall health and vitality of forest ecosystems (Berrios et al. 2024; Hobbie 2006; Gil-Martinez et al. 2018). In agricultural settings, nitrogen is often added to crops for maximizing growth; however, in forest systems, nitrogen may already be plentiful.

Nitrogen availability plays a role in forest carbon cycling as forests store large quantities of nitrogen within the residue of organic matter. However, the impact of inorganic nitrogen fertilizers on forest ecosystems remains highly debated, with varying perspectives on how their use may influence nutrient dynamics and ecosystem processes. Phillips et al. (2013) observed that tree growth benefits from EMF when soils are depleted of nitrogen, suggesting that nitrogen fertilization protocols in forest ecosystems may negatively impact mycorrhizal networks. Therefore, assessing nitrogen levels and management strategies in forest ecosystems is essential to preserve mycorrhizal networks, which in turn enhance carbon sequestration, support biodiversity, and provide long-term ecological and economic benefits. Forest managers can integrate knowledge of EMF into sustainable forestry practices, which may reduce dependency on chemical fertilizers and ensure a balanced nutrient cycle.

Beyond their role in nitrogen dynamics, EMF may play a role in carbon sequestration through several mechanisms, including fixing carbon belowground and adding to fungal necromass (dead mycorrhizal mycelium) (Clemmensen et al. 2013; Hawkins et al. 2023; Phillips et al. 2013). Some EMF may reduce the decomposition activity of other free-living decomposers in the soil by blocking access to carbon (Querejeta et al. 2021). These free-living organisms include bacteria, fungi, and some invertebrates that do not rely on a symbiotic relationship to break down organic matter.

Furthermore, not only are EMF the dominant fungi in the forest's surface soil layer, where organic matter is abundant, but they are also prevalent in the deeper soil layers where decomposers are less abundant, significantly contributing to soil carbon sequestration (Clemmensen et al. 2013; Treseder and Holden 2013). EMF may address the continuous rise of atmospheric carbon (Nunes 2023) with its roles in sequestering carbon and in contributing to plant stress tolerance under such conditions.

Plant Resilience and Stress Tolerance

Ectomycorrhizal associations confer a remarkable degree of resilience and stress tolerance to host plants by facilitating the transmission of signaling molecules. This activation of the plant's defense mechanisms enhances its capacity to withstand both biotic and abiotic stresses. In times of environmental stress, such as drought, EMF aid plants by improving water uptake and retention (Li et al. 2021; Sevanto et al. 2023). Additionally, the symbiotic relationship enhances the plant's resistance to various pathogens and pests, thereby reducing the susceptibility of forests to disease outbreaks (Smith and Read 2008). This can occur through increasing plant cell walls, altering root exudates, or outcompeting pathogens. EMF have been shown to induce systemic resistance against cabbage looper in non-mycorrhizal plants (Vishwanathan et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2022). These fungi can stimulate phytohormones, which activate a defense response in plants when attacked by pathogenic organisms (Gille et al. 2023). Just as EMF support trees in coping with local stressors, they also play a role in addressing global challenges like climate change.

Climate Change Mitigation

Improving our forests is imperative for combating climate change, and EMF can support this process. EMF play a significant role in mitigating climate change, particularly for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Although elevated carbon dioxide levels can alter EMF-plant interactions (Godbold et al. 1997), they facilitate the conversion of carbon into stable sinks within plant biomass, soil microbial communities, and soil carbon pools (Ainsworth and Long 2005). Field and laboratory experiments have shown that increased atmospheric carbon dioxide levels significantly boost total plant biomass, EMF abundance, microbial biomass, and soil carbon storage (Wang 2007; Bradford et al. 2008). This enhancement may occur because elevated carbon dioxide enriches EMF pathways for biochemical activity, promoting fungal branching and further colonization of plant roots, which potentially create a positive feedback loop that increases plant biomass production and carbon allocation to the soil. Additionally, EMF can buffer trees against temperature fluctuations and water scarcity that are intensified by global warming (Gehring et al. 2017; Steidinger et al. 2019). Not only can EMF bolster forested systems in the wake of climate change, but they can assist in establishing plants on degraded landscapes.

EMF in Pollution Remediation

Following evidence of their effectiveness in protecting plants from heavy metal toxicity, EMF have also been explored for their potential in pollution remediation. In recent years, land managers and scientists have turned to fungi for remediation of polluted sites. Ectomycorrhizal fungi may take in toxic chemicals, which are then degraded to inert compounds by enzymes or moved to other plant parts (Assad et al. 2020). A study showed that EMF degrade or mineralize some of the most carcinogenic and damaging pesticides, although further study is needed to determine the long-term benefit to forest and managed systems (Huang et al. 2007). Persistent chemicals can remain in Florida soils from agricultural and industrial activities. However, EMF could remediate these sites by restoring soil and water quality, thereby supporting sustainable land use, reclamation efforts, and environmental stewardship.

Implications for Forest Management and Ecological Balance

EMF are indispensable for the functioning of both natural and managed forest landscapes, providing essential services such as biogeochemical cycling, enhancing plant resilience, improving soil structure, and fostering ecosystem diversity. These underground symbiotic relationships between fungi and woody plants play a pivotal role in shaping the resilience of forest ecosystems, influencing species diversity, and addressing environmental challenges.

Forest managers, nursery operators, timber stakeholders, and land stewards can incorporate EMF into management plans to address challenges such as pollution remediation, reforestation, soil degradation, and carbon sequestration. By using EMF, land managers have the potential to decrease costs and chemical inputs, improve soil health, enhance plant growth and resilience, and increase biodiversity, all of which strengthen the overall health of forested ecosystems. In Florida, where ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to climate and human-induced pressures, land managers can leverage the benefits of EMF to ensure sustainability in forested and managed ecosystems.

By supporting forest health and stability, EMF interactions have profound ecological importance, offering solutions to contemporary forest management issues and contributing to climate stability for future generations. Informed application of this knowledge can help stakeholders make decisions that benefit the environment and economic viability of forest ecosystems. To demonstrate the different ways EMF have been studied and applied, Table 1 highlights the benefits EMF provide to forest growth and ecosystem services.

Table 1. The representative greenhouse studies or field trials that highlight the benefits of EMF to the growth and resilience of specific tree or woody species.

Integrating Key Points

As incredibly beneficial fungi, EMF form partnerships with tree roots that are critical in Florida’s forest ecosystems, particularly in northern Florida, where pine plantations contribute significantly to Florida’s economy. These fungi form symbiotic relationships with tree roots, helping them with nutrient cycling, carbon storage, and water retention. The northern part of Florida is the area most prone to drought. EMF can assist during times of drought to take in more water and nutrients to buffer the stress on local pine species. They can be used to minimize the effect of diseases and pests on trees to keep forests healthier.

EMF help tree seeds survive and grow more resilient, which is especially useful for facing stresses such as drought, heat, and salinity in Florida’s climate. They are vital in helping forests recover after natural or man-made disturbances such as hurricanes, forest fires, clearing, or pollution. Further, they may be useful in remediation efforts to restore soils and stabilize erosion. EMF play a pivotal role in improving the ability of Florida’s forests to adapt to climate change. As temperatures rise and rainfall patterns change, EMF improve carbon storage, maintain growth, and enable trees to cope with stress.

Understanding the functions of EMF benefits forest managers, nursery operators, and land stewards as they can use EMF to restore soil health, improve tree growth, and enhance forest resilience, all of which are vital to Florida’s forest systems. Incorporating EMF into forest management practices could reduce chemical inputs and their associated costs while sustaining the forest growth necessary in the timber industry. Leveraging EMF in Florida’s forest management can create sustainable ecosystems that benefit both the environment and local communities.

Glossary of Specialized Terms

Ascomycota is a large group of fungi that produce their spores in sac-like structures called asci. These fungi can include yeast, molds, and some mushrooms. They are important because they break down dead plants and animals.

Basidiomycota is a group of fungi that includes mushrooms, puffballs, and shelf fungi. They help break down dead plants and trees.

Mycelial network is a system of branching, thread-like hyphae, which serve a similar function to roots. This network spreads through the soil, helping the fungus absorb nutrients and water.

Reactive oxygen species include a variety of reactive, oxidant molecules that can turn on or off different biological functions. They play a role in aging and genetic mutations. They are also capable of degrading organic pollutants.

References

Ainsworth, E. A., and S. P. Long. 2005. “What have we learned from 15 years of free‐air CO2 enrichment (FACE)? A meta‐analytic review of the responses of photosynthesis, canopy properties and plant production to rising CO2.” New Phytologist 165 (2): 351–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01224.x

Alvarez, M., D. Huygens, C. Fernandez, et al. 2009. “Effect of Ectomycorrhizal Colonization and Drought on Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism of Nothofagus dombeyi Roots.” Tree Physiology 29 (8): 1047–1057. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpp038

Andres, H., H.-L. Liao, and K. Zhang. 2025. “Biology, Ecology, and Benefits of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Agricultural Ecosystems: PP383, 3/2025.” EDIS 2025 (2). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-pp383-2025

Anthony, M. A., T. W. Crowther, S. van der Linde, et al. 2022. “Forest tree growth is linked to mycorrhizal fungal composition and function across Europe.” The ISME Journal 16 (5): 1327–1336. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-021-01159-7

Aryal, P., S. J. Meiners, and B. S. Carlsward. 2021. “Ectomycorrhizae determine chestnut seedling growth and drought response.” Agroforestry Systems 95: 1251–1260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-020-00488-4

Assad, R., Z. A. Reshi, I. Rashid, and Y. Shouche. 2020. “Role of Ectomycorrhizal Biotechnology in Pesticide Remediation.” Bioremediation and Biotechnology 3: 315–330. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46075-4_14

Bandou, E., F. Lebailly, F. Muller, et al. 2006. “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Scleroderma bermudense alleviates salt stress in seagrape (Coccoloba uvifera L.) seedlings.” Mycorrhiza 16: 559–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-006-0073-6

Baslam, M., I. Garmendia, and N. Goichoechea. 2011. “Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) improved growth and nutritional quality of greenhouse-grown lettuce.” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 59 (10): 5504–5515. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf200501c

Bauman, J. M., C. H. Keiffer, and S. Hiremath. 2012. “Facilitation of American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) Seedling Establishment by Pinus virginiana in Mine Restoration.” International Journal of Ecology 2012: 257326. https://research.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/41681

Begum, N., C. Qin, M. A. Ahanger, et al. 2019. “Role of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Plant Growth Regulation: Implications in Abiotic Stress Tolerance.” Frontiers in Plant Science 10: 1068. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01068

Berrios, L., G. D. Bogar, A. M. Venturini, et al. 2024. “Ectomycorrhizal fungi alter soil food webs and the functional potential of bacterial communities.” ASM Journals 9 (6): e00369-24. https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00369-24

Birhane, E., F. Sterck, M. Fetene, F. Bongers, and T. Kuyper. 2012. “Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance photosynthesis, water use efficiency, and growth of frankincense seedlings under pulsed water availability conditions.” Oecologia 169: 895–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-012-2258-3

Bradford, M. A., N. Fierer, and J. F. Reynolds. 2008. “Soil carbon stocks in experimental mesocosms are dependent on the rate of labile carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus inputs to soils.” Functional Ecology 22 (6): 964–974. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01404.x

Branco, S., A. Schauster, H.-L. Liao, and J. Ruytinx. 2022. “Mechanisms of Stress Tolerance and Their Effects on the Ecology and Evolution of Mycorrhizal Fungi.” New Phytologist 235 (6): 2158–2175. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.18308

Cahanovitc, R., S. Livne-Luzon, R. Angel, and T. Klein. 2022. “Ectomycorrhizal fungi mediate belowground carbon transfer between pines and oaks.” The ISME Journal 16 (5): 1420–1429. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-022-01193-z

Chen, S., H. Zhao, C. Zou, et al. 2017. “Combined inoculation with multiple arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improves growth, nutrient uptake and photosynthesis in cucumber seedlings.” Frontiers in Microbiology 8: 2516. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02516

Chot, E., and M. S. Reddy. 2022. “Role of Ectomycorrhizal Symbiosis Behind the Host Plants Ameliorated Tolerance Against Heavy Metal Stress.” Frontiers in Microbiology 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.855473

Clemmensen, K. E., A. Bahr, O. Ovaskainen, et al. 2013. “Roots and associated fungi drive long-term carbon sequestration in boreal forest.” Science 339 (6127): 1615–1618. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1231923

Colpaert, J. V., J. H. L. Wevers, E. Krznaric, and K. Adriaensen. 2011. “How Metal-Tolerant Ecotypes of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi Protect Plants from Heavy Metal Pollution.” Annals of Forest Science 68: 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-010-0003-9

Corrales, A., T. W. Henkel, and M. E. Smith. 2018. “Ectomycorrhizal Associations in the Tropics—Biogeography, Diversity Patterns and Ecosystem Roles.” New Phytoloist 220 (4): 1076–1091. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15151

De Quesada, G., J. Xu, Y. Salmon, et al. 2024. “The Effect of Ectomycorrhizal Fungal Exposure on Nursery-Raised Pinus sylvestris Seedlings: Plant Transpiration Under Short-Term Drought, Root Morphology and Plant Biomass.” Tree Physiology 44 (4): tpae029. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpae029

Figueiredo, A. F., J. Boy, and G. Guggenberger. 2021. “Common Mycorrhizae Network: A Review of the Theories and Mechanisms Behind Underground Interactions.” Frontiers in Fungal Biology 2: 735299. https://doi.org/10.3389/ffunb.2021.735299

Franco, A. R., N. R. Sousa, M. A. Ramos, R. S. Oliveira, and P. M. L. Castro. 2014. “Diversity and Persistence of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi and Their Effect on Nursery-Inoculated Pinus pinaster in a Post-Fire Plantation in Northern Portugal.” Microbial Ecology 68: 761–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-014-0447-9

Gehring, C. A., C. M. Sthultz, L. Flores-Rentería, A. V. Whipple, and T. G. Whitham. 2017. “Tree genetics defines fungal partner communities that may confer drought tolerance.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 114 (42): 11169–11174. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1704022114

Gil-Martinez, M., Á. López-Garcia, M. T. Domínguez, et al. 2018. “Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities and their functional traits mediate plant-soil interactions in trace element contaminated soils.” Frontiers in Plant Science 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01682

Gille, C. E., P. M. Finnegan, P. E. Hayes, et al. 2023. “Facilitative and Competitive Interactions Between Mycorrhizal and Nonmycorrhizal Plants in an Extremely Phosphorus-Impoverished Environment: Role of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi and Native Oomycete Pathogens in Shaping Species Coexistence.” New Phytologist 242 (4): 1630–1644. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19489

Hage-Ahmed, K., K. Rosner, and S. Steinkellner. 2018. “Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Their Response to Pesticides.” Pest Management Science 75 (3): 583–590. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.5220

Hawkins, H.-J., R. I. M. Cargill, M. E. Van Nuland, et al. 2023. “Mycorrhizal Mycelium as a Global Carbon Pool.” Current Biology 33 (11): R560–R573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.02.027

Herman, D. J., M. K. Firestone, E. Nuccio, and A. Hodge. 2011. “Interactions Between an Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus and a Soil Microbial Community Mediating Litter Decomposition.” Federation of European Microbiological Societies 80 (1): 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01292.x

Hobbie, E. A. 2006. “Carbon allocation to ectomycorrhizal fungi correlates with belowground allocation in culture studies.” Ecology 87 (3): 563–569. https://doi.org/10.1890/05-0755

Hock, B. 2012. Fungal Associations, edited by Karl Esser. 2nd ed. The Mycota Vol. 9. Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-30826-0

Huang, Y., X. Zhao, and S. Luan. 2007. “Uptake and Biodegradation of DDT by 4 Ectomycorrhizal Fungi.” Science of the Total Environment 385 (1–3): 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.04.023

Godbold, D. L., G. M. Berntson, and F. A. Bazzaz. 1997. “Growth and Mycorrhizal Colonization of Three North American Tree Species Under Elevated Atmospheric CO2.” New Phytologist 137 (3): 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.1997.00842.x

Johnson, D., F. Martin, J. W. G. Cairney, and I. C. Anderson. 2012. “The Importance of Individuals: Intraspecific Diversity of Mycorrhizal Plants and Fungi in Ecosystems.” New Phytologist 194 (3): 614–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04087.x

Karlsen-Ayala, E., M. E. Smith, B. C. Askey, and R. Gazis. 2022. “Native ectomycorrhizal fungi from the endangered pine rocklands are superior symbionts to commercial inoculum for slash pine seedlings.” Mycorrhiza 32: 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-022-01092-3

Kebert, M., S. Kostić, E. Čapelja, et al. 2022. “Ectomycorrhizal Fungi Modulate Pedunculate Oak’s Heat Stress Responses through the Alternation of Polyamines, Phenolics, and Osmotica Content.” Plants 11 (23): 3360. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11233360

Kumar, J., and N. S. Atri. 2017. “Studies on Ectomycorrhiza: An Appraisal.” Botanical Review 84: 108–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12229-017-9196-z

Lapeyrie, F., C. Picatto, J. Gerard, and J. Dexheimer. 1990. “T.E.M. Study of Intracellular and Extracellular Calcium Oxalate Accumulation by Ectomycorrhizal Fungi in Pure Culture or in Association with Eucalyptus Seedlings.” Symbiosis 9: 163–166.

Li, Y., T. Zhang, Y. Zhou, et al. 2021. “Ectomycorrhizal symbioses increase soil calcium availability and water use efficiency of Quercus acutissima seedlings under drought stress.” European Journal of Forest Research 140: 1039–1048. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-021-01383-y

Luo, Z.-B., K. Li, Y. Gai, et al. 2011. “The ectomycorrhizal fungus (Paxillus involutus) modulates leaf physiology of poplar towards improved salt tolerance.” Environmental and Experimental Botany 72 (2): 304–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2011.04.008

Luo, Z.-B., C. Wu, C. Zhang, H. Li, U. Lipke, and A. Polle. 2014. “The Role of Ectomycorrhizas in Heavy Metal Stress Tolerance of Host Plants.” Environmental and Experimental Botany 108: 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2013.10.018

Ma, Y., J. He, C. Ma, et al. 2014. “Ectomycorrhizas with Paxillus involutus enhance cadmium uptake and tolerance in Populus × canescens.” Plant, Cell & Environment 37 (3): 627–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.12183

Martin, F., A. Kohler, C. Murat, C. Veneault-Fourrey, and D. S. Hibbett. 2016. “Unearthing the Roots of Ectomycorrhizal Symbioses.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 14: 760–773. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2016.149

Mateus, P., F. Sousa, M. Martins, et al. 2024. “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Paxillus involutus positively modulates Castanea sativa Miller (var. Marsol) responses to heat and drought co-exposure.” Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 215: 108999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.108999

Meeds, J. A., J. M. Kranabetter, I. Zigg, et al. 2021. “Phosphorus deficiencies invoke optimal allocation of exoenzymes by ectomycorrhizas.” The ISME Journal 15: 1478–1489. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-00864-z

Nunes, L. J. R. 2023. “The Rising Threat of Atmospheric CO2: A Review on the Causes, Impacts, and Mitigation Strategies.” Environments 10 (4): 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments10040066

Nygren, C. M. R., J. Edqvist, M. Elfstrand, G. Heller, and A. F. S. Taylor. 2007. “Detection of Extracellular Protease Activity in Different Species and Genera of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi.” Mycorrhiza 17: 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-006-0100-7

Phillips, L. A., V. Ward, and M. D. Jones. 2013. “Ectomycorrhizal fungi contribute to soil organic matter cycling in sub-boreal forests.” The ISME Journal 8 (3): 699–713 https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.195

Policelli, N., T. R. Horton, A. T. Hudon, T. R. Patterson, and J. M. Bhatnagar. 2020. “Back to Roots: The Role of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi in Boreal and Temperate Forest Restoration.” Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2020.00097

Querejeta, J. I., K. Schlaeppi, Á. López-Garcia, et al. 2021. “Lower relative abundance of ectomycorrhizal fungi under a warmer and drier climate is linked to enhanced soil organic matter decomposition.” New Phytologist 232 (3): 1399–1413. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17661.

Ruytinx, J., L. Coninx, H. Nguyen, et al. 2017. “Identification, Evolution and Functional Characterization of Two Zn CDF‐Family Transporters of the Ectomycorrhizal Fungus Suillus luteus.” Environmental Microbiology Reports 9 (4): 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-2229.12551

Sebastiana, M., A. B. da Silva, A. R. Matos, A. Alcântara, S. Silvestre, and R. Malhó. 2018. “Ectomycorrhizal inoculation with Pisolithus tinctorius reduces stress induced by drought in cork oak.” Mycorrhiza 28: 247–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-018-0823-2

Sevanto, S., C. A. Gehring, M. G. Ryan, et al. 2023. “Benefits of symbiotic ectomycorrhizal fungi to plant water relations depend on plant genotype in pinyon pine.” Scientific Reports 13: 14424. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41191-5

Smith, S. E., and D. J. Read. 2008. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. 3rd Edition. Academic Press.

Steidinger, B. S., T. W. Crowther, J. Liang, et al. 2019. “Climatic controls of decomposition drive the global biogeography of forest-tree symbioses.” Nature 569: 404–408. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1128-0

Stuart, E. K., and K. L. Plett. 2020. “Digging Deeper: In Search of the Mechanisms of Carbon and Nitrogen Exchange in Ectomycorrhizal Symbioses.” Frontiers in Plant Science 10: 1658. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01658

Sun, W., B. Yang, Y. Zhu, H. Wang, G. Qin, and H. Yang. 2022. “Ectomycorrhizal fungi enhance the tolerance of phytotoxicity and cadmium accumulation in oak (Quercus acutissima Carruth.) seedlings: Modulation of growth properties and the antioxidant defense responses.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29: 6526–6537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-16169-3

Tang, Y., L. Shi, K. Zhong, Z. Shen, Y. Chen. 2019. “Ectomycorrhizal fungi may not act as a barrier inhibiting host plant absorption of heavy metals.” Chemosphere 215: 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.09.143

Thomson, B. D., T. S. Grove, N. Malajczuk, and G. E. St J. Hardy. 1994. “The Effectiveness of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi in Increasing the Growth of Eucalyptus globulus Labill. in Relation to Root Colonization and Hyphal Development in Soil.” New Phytologist 126: 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb04250.x

Treseder, K. K., and S. R. Holden. 2013. “Fungal Carbon Sequestration.” Science 339 (6127): 1528–1529.

van der Heijden, M. G. A., and T. R. Horton. 2009. “Socialism in Soil? The Importance of Mycorrhizal Fungal Networks for Facilitation in Natural Ecosystems.” Journal of Ecology 97 (6): 1139–1150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01570.x

van der Heijden, M. G. A., F. M. Martin, M.-A. Selosse, and I. R. Sanders. 2015. “Mycorrhizal Ecology and Evolution: The Past, the Present, and the Future.” New Phytologist 205 (4): 1406–1423. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13288

Vincent, B., and S. Declerck. 2021. “Ectomycorrhizal Fungi and Trees: Brothers in Arms in the Face of Anthropogenic Activities and Their Consequences.” Symbiosis 84: 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13199-021-00792-2

Vishwanathan, K., K. Zienkiewicz, Y. Liu, et al. 2020. “Ectomycorrhizal fungi induce systemic resistance against insects on a nonmycorrhizal plant in a CERK1-dependent manner.” New Phytologist 228 (2): 728–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16715

Walker, R. F. 1999. “Reforestation of an Eastern Sierra Nevada Surface Mine with Containerized Jeffrey Pine: Seedling Growth and Nutritional Responses to Controlled Release Fertilization and Ectomycorrhizal Inoculation.” Journal of Sustainable Forestry 9 (3–4): 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1300/J091v09n03_06

Wang, X. 2007. “Effects of Species Richness and Elevated Carbon Dioxide on Biomass Accumulation: A Synthesis Using Meta-Analysis.” Oecologia 152: 595–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-007-0691-5

Wang, H., K. Zhang, R. Tappero, et al. 2025. “Inorganic nitrogen and organic matter jointly regulate ectomycorrhizal fungi‐mediated iron acquisition.” New Phytologist 245 (6): 2715–2725. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.20394

Wang, J., H. Zhang, J. Gao, Y. Zhang, Y. Liu, and M. Tang. 2021. “Effects of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi (Suillus variegatus) on the Growth, Hydraulic Function, and Non-Structural Carbohydrates of Pinus tabulaeformis Under Drought Stress.” BMC Plant Biology 21: 171. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-021-02945-3

Yin, D., R. Song, J. Qi, and X. Deng. 2018. “Ectomycorrhizal fungus enhances drought tolerance of Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica seedlings and improves soil condition.” Journal of Forestry Research 29: 1775–1788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-017-0583-4

Yin, D., H. Wang, and J. Qi. 2021. “The Enhancement Effect of Calcium Ions on Ectomycorrhizal Fungi-Mediated Drought Resistance in Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 40: 1389–1399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-020-10197-y

Zalesny, R. S., W. L. Headlee, G. Gopalakrishnan, et al. 2019. “Ecosystem Services of Poplar at Long-Term Phytoremediation Sites in the Midwest and Southeast, United States.” WIREs Energy and Environment 8 (6): e349. https://doi.org/10.1002/wene.349

Zhang, K., R. Tappero, J. Ruytinx, S. Branco, and H.-L. Liao. 2021. “Disentangling the Role of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi in Plant Nutrient Acquisition Along a Zn Gradient Using X-ray Imaging.” The Science of the Total Environment 801: 149481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149481

Zhang, K., H. Wang, R. Tappero, et al. 2023. “Ectomycorrhizal fungi enhance pine growth by stimulating iron‐dependent mechanisms with trade‐offs in symbiotic performance.” New Phytologist 242 (4): 1645–1660. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19449

Zhang, L., W. A. N. G. Ming-Xia, L. I. Hua, Y. U. A. N. Ling, J. G. Huang, and C. Penfold. 2014. “Mobilization of Inorganic Phosphorus from Soils by Ectomycorrhizal Fungi.” Pedosphere 24 (5): 683–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0160(14)60054-0

Zhang, W., L. Yu, B. Han, K. Liu, and X. Shao. 2022. “Mycorrhizal inoculation enhances nutrient absorption and induces insect-resistant defense of Elymus nutans.” Frontiers in Plant Science 13: 898969. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.898969

Zheng, W., E. K. Morris, and M.C. Rillig. 2014. “Ectomycorrhizal fungi in association with Pinus sylvestris seedlings promote soil aggregation and soil water repellency.” Soil Biology and Biochemistry 78: 326–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.07.015

Zhu, X. C., F. B. Song, S. Q. Liu, and T. D. Liu. 2011. “Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus on Photosynthesis and Water Status of Maize Under High Temperature Stress.” Plant and Soil 346: 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-011-0809-8