An Introduction to the Wonderful World of Butterflies

Butterflies belong to the order Lepidoptera, which is shared with their close cousins the moths. Butterflies encompass a remarkable diversity with an array of shapes, sizes, and intricate wing patterns (Figure 1). There are approximately 750 butterfly species in the United States, representing a diversity of species with different shapes and sizes (Scott 1992; Warren et al. 2024). Although there are fewer species of butterflies than their well-known counterparts, moths, which have over 10,000 species in North America alone (Pickering et al. 2016), butterflies hold significant ecological importance. They are essential pollinators and occupy vital positions in the food chain, serving as an important food source for many other living things, especially caterpillars—the larval stage of butterflies. Butterflies live in various habitats worldwide, ranging from forests, wetlands, grasslands, and meadows to urban areas. Because of their ubiquity and diversity and the ease with which they can be observed, butterflies offer an excellent opportunity to document the biodiversity around you.

Observations of butterflies help scientists track population trends, identify species at risk, and study the impacts of environmental changes on their populations. Furthermore, observations contribute to our broader knowledge of insect biology and evolution, unraveling fascinating adaptations, behaviors, and ecological relationships. An individual can make meaningful contributions to science by documenting butterflies and sharing their observations on platforms like iNaturalist. Each observation becomes a valuable data point, collectively contributing to a better understanding of butterflies and the ecosystems they inhabit. iNaturalist has been critical in documenting the first known photographs of over 800 species of living butterflies, most of which are from the tropics (Mesaglio et al. 2021). Sometimes, species new to science are even discovered through iNaturalist (PYRCZ et al. 2024). By observing, photographing, and recording information about butterflies, anyone can participate in this scientific endeavor, playing a critical role in advancing our understanding of butterflies. Even if you live in urban areas, it is valuable to document butterflies to better understand how they respond to the urban environment — observations from everywhere are valuable!

The purpose of this document is to provide guidance and tips on how to enter the wonderful world of butterflies and how to leverage iNaturalist to document butterfly observations through citizen science. The intended audience is anyone who is interested in the natural world and wants to learn more about observing butterflies, identifying butterflies, and contributing to science by adding their observations to iNaturalist. While we use examples throughout Florida, the majority of the information presented here is highly relevant for beginner butterfly-enthusiasts anywhere in the world.

Corey Callaghan and Brittany Mason, UF/IFAS

Using iNaturalist to Document and Identify Butterflies

iNaturalist, at https://www.inaturalist.org, is a citizen science platform that combines the wonders of nature with the collective crowdsourcing efforts of a global community. iNaturalist is an independent multi-taxa platform, allowing participants to contribute observations of any organism, or traces thereof, along with information about where and when that observation took place. The program is free to use and can be accessed via a user-friendly website and mobile app. The key to iNaturalist’s success lies in the precision and thoroughness of the contributed observations. Achieving an accurate identification for an observation can be a challenge, but each user can use their own experience and knowledge to type in their own identification. When users post organisms unknown to them, the auto-ID suggestion, which provides a list of species that match the supplied photograph and location, can be a great way for them to get the ball rolling to identify the observation. This suggestion is provided by a computer vision algorithm that is constantly improving, aided by the iNaturalist community of identifiers that correct and confirm identifications (see more in their blog post about vision model updates). Supplying accurate information about species and locations creates contributions that become valuable data points and help researchers, conservationists, and policymakers understand and safeguard the natural world. For these reasons, iNaturalist is an excellent tool to help you jump into the world of butterflies. For more information on iNaturalist, see iNaturalist’s “About” page, and see their “Getting Started” collection of pages for further details on how to get started. Atlas of Living Australia, at https://ala.org.au, has published a comprehensive guide on the ins and outs of iNaturalist.

As of 2024, of the approximately 19,500 species of butterflies in the world, 13,287 have been submitted to iNaturalist. In the United States, 729 butterfly species with 5 or more observations have been submitted to iNaturalist with the most reported butterflies being monarch, eastern tiger swallowtail, Gulf fritillary, red admiral, black swallowtail, pearl crescent, common buckeye, fiery skipper, small white, and painted lady (Figure 2). In Florida, 181 butterfly species have been submitted to iNaturalist with the most reported butterflies being the Gulf fritillary, monarch, white peacock, zebra longwing, Horace’s duskywing, common buckeye, fiery skipper, long-tailed skipper, eastern giant swallowtail, and Atala (Figure 2).

Figure produced from iNaturalist data

Finding and Observing Butterflies

Butterflies are ubiquitous and can be found in nearly every habitat type in the world, but there are some tips and techniques that can maximize the diversity of species you find. Further, these tips will also aid in searching out specific species. In this section we will cover some of these different strategies, ranging from finding a high diversity of butterflies by targeting specific habitat types, encouraging butterflies to “come to you” in your yard, to information you should know to help you target specific species (Figure 3).

Corey Callaghan and Brittany Mason, UF/IFAS

Search by habitat.

Butterflies can be found in a wide range of habitats, from forests and wetlands to grasslands and urban gardens (Figure 4). Different habitats host different species, and some butterflies are more habitat-specific than others. In forests, look for butterflies in clearings and along trails where sunlight can penetrate. Powerlines cut within forests often provide open spaces that attract a variety of butterflies. Wetlands such as creeks, streams, and rivers are excellent places to find butterflies, as these areas provide moisture and an abundance of flowering plants that attract them. Grasslands and meadows, including small roadside edges and borders with flowers, are highly productive for many butterfly species. These open spaces are rich in flowering plants, which can attract a variety of butterflies. Even within urban areas, gardens, parks, and roadside edges can be highly productive, especially if they feature a variety of flowering plants. Many cities have designated butterfly gardens or pollinator gardens with native plants, which are excellent spots for observing a diversity of butterfly species. In general, areas with native flowers tend to support a higher diversity of butterfly species (Forister, Pelton, and Black 2019). Exploring different habitats and paying attention to the presence of flowering plants can greatly enhance your butterfly-watching experience. It is important to also keep in mind that butterflies often use specific microhabitats within larger habitats. For example, some species may prefer forest edges, while others may be found in sunny glades or near water sources. Some butterflies, like certain hairstreaks, prefer to fly high in the canopy, rarely coming down to our level. Observing from a higher vantage point, such as a hill or a tree platform, can help you spot these elusive species. Other butterflies, like swallowtails and sulphurs, are attracted to moist soil or mud where they can sip minerals and nutrients. While this is uncommon in North America, it can be quite common in the tropics, and a sight to see when found! Being aware of these types of microhabitats can increase your chances of finding specific species.

Corey Callaghan and Brittany Mason, UF/IFAS

Attract butterflies to your yard.

Creating a butterfly-friendly environment in your yard can significantly increase your chances of observing butterflies, with the added bonus of not having to travel far to see them! There are a few key tips to help maximize the diversity of butterflies that might visit your yard. First, plant native plants. Native plants are more likely to attract local butterfly species. Aim for a variety of plants that bloom at different times of the year to provide a continuous food source. There are many resources that provide guidance on plants that are good for butterflies, for example, Ask IFAS’s “Butterfly Gardening in Florida,” at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu. We suggest whenever possible to use integrated pest management for pest control in these gardens, keeping in mind potential nontarget impacts on the butterflies and caterpillars you are trying to attract in the first place. Lastly, creating a variety of habitat types — dense shrubs, tall grasses, and piles of leaves or logs — can provide necessary shelter and places for butterflies to rest, maximizing the likelihood they’ll be using your backyard.

Know butterflies’ temporal patterns.

Butterflies exhibit distinct seasonal and daily activity patterns that influence when and where you might find them. In general, butterfly diversity peaks during spring and summer when temperatures are warm, the days are long, and flowers are abundant. This is the best time to observe a wide variety of species. However, in warmer climates like Florida or tropical regions, you can find butterflies year-round. Even in these regions, there will be periods where butterflies are more abundant. For example, the rainy season in tropical areas often brings an influx of butterflies due to the increased availability of nectar and host plants.

Butterflies are generally most active during the late morning and early afternoon when the sun is shining. They bask in the sun to raise their body temperature, which is essential for flight. Observing butterflies during these times can yield the most sightings. However, different species exhibit unique activity patterns. For example, some butterflies, such as satyrs, are crepuscular and are more often seen during the early morning or late afternoon.

When targeting specific butterfly species, it is important to understand their flight periods. Some species fly year-round, while others have very short flight periods, sometimes lasting only a week or two. Knowing the specific timing of these flight periods and planning your observation trips accordingly can help you spot more butterflies and a greater variety of butterfly species. To increase your chances of finding specific butterfly species, it is beneficial to research their unique temporal preferences, which is easily accomplished by consulting field guides or online resources such as iNaturalist (Figure 5).

Corey Callaghan and Brittany Mason, UF/IFAS; graphs are website screenshots from iNaturalist.org

Learn host plants.

Butterflies lay their eggs on specific host plants. A well-known example is the monarch butterfly, which lays eggs on milkweed. Pay close attention to host plants, and you may find larvae of various sizes within their foliage. If you want to target specific species that you would really like to see, you could research the host plants of those butterflies and then search out where to find those host plants. Combining this host plant knowledge with knowledge about butterfly flight periods can maximize the possibility of a successful search for a particular species!

Other Tips and Techniques

Above are only some general approaches to searching for butterflies, but here we provide a handful of additional tips and techniques that can enhance your butterfly-finding and observing.

Butterfly Nets

Butterfly nets are useful tools for up-close-and-personal encounters. They are useful tools to temporarily capture butterflies. Often, they are useful in combination with mesh tents or jars where details of the butterfly can be observed. Just be sure not to handle the butterfly for too long and to release it promptly in the same area where you captured it.

Patience and Behavior

Butterflies can be skittish, fast, and elusive, so patience is key. Even when you are fortunate enough to find a butterfly, it can take extreme patience to be able to get the kind of clear, detailed photo that is necessary to allow iNaturalist users to identify the species. Move slowly and avoid sudden movements. Learn about the specific behaviors of the butterflies you are observing. For example, some species prefer to feed on certain flowers or have unique flight patterns, while others will “patrol” specific areas and will often come back to the same perch, even if it takes 5 to 10 minutes.

Setting Up Butterfly Feeders

You can attract some species of butterflies to a specific spot in your yard by setting up feeders. Fill shallow dishes with overripe fruit, sugar water, or a solution of water and honey. Place the feeders in a sunny spot to make them more attractive to butterflies. This can be a particularly useful tip in the tropics.

Best Practices for Taking Photos of Butterflies for Identification

Many factors come into play when photographing and identifying butterflies. Thankfully, most butterfly species are quite distinct and can often be identified with just a single photo. Still, a general rule of thumb is to capture photos from two or more angles. The angles you aim for may depend on the individual butterfly since different species come in many shapes and hold their wings in different ways. Close-up shots of wing patterns, coloration, and any unique markings or features can aid in distinguishing between species. To identify and classify butterfly observations accurately, focus on capturing clear images of the butterfly’s wings, highlighting the patterns and coloration. Pay attention to details such as the shape of the wings, presence of specific markings or lines, and any unique features like antennae shape and color. Although most butterfly species present a straightforward identification process with good images, it is important to note that some butterfly species are extremely similar and therefore difficult to identify from photos alone (Figure 6).

Atala photo by Brittany Mason, UF/IFAS; great purple hairstreak photo by Glenn Perelson (CC BY-NC-SA)

When it comes to cameras, butterfly newcomers often use smartphones. These cameras work well for larger butterflies when there is appropriate lighting. Point-and-shoot cameras with macro options can help improve image quality but a DSLR or mirrorless camera with a macro lens and an external flash and flash diffuser will provide the highest quality images. Depending on the species, zoom lenses may allow you to capture an identifiable image without having to approach too close. Whether using a smartphone or a specialized lens on a digital camera, an important step that is often overlooked is image cropping. Because iNaturalist uses computer vision to generate ID suggestions, a tight crop of your butterfly can help filter out any distractions and will lead to a more accurate automated ID. Furthermore, cropped images are more likely to get the attention of an iNaturalist identifier of butterflies. In addition to cropping images, orientating a butterfly so its head is directly at the top of the image or to the left or right if the butterfly is holding its wings closed, will help facilitate comparison of your images to those found in field guides and on databases online. Many photo editing programs allow images to be rotated by single degrees rather than by 90 degrees, allowing images to be corrected. See Figure 7 for an example. Photographing butterflies takes practice, and we recommend visiting butterfly houses, such as the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera, to practice photography skills. But remember that only wild organisms should be uploaded to iNaturalist. Non-wild organisms are tolerated on iNaturalist, but must be marked as casual if uploaded.

Corey Callaghan and Brittany Mason, UF/IFAS

A Deeper Dive on Using iNaturalist to Understand the World of Butterflies near You

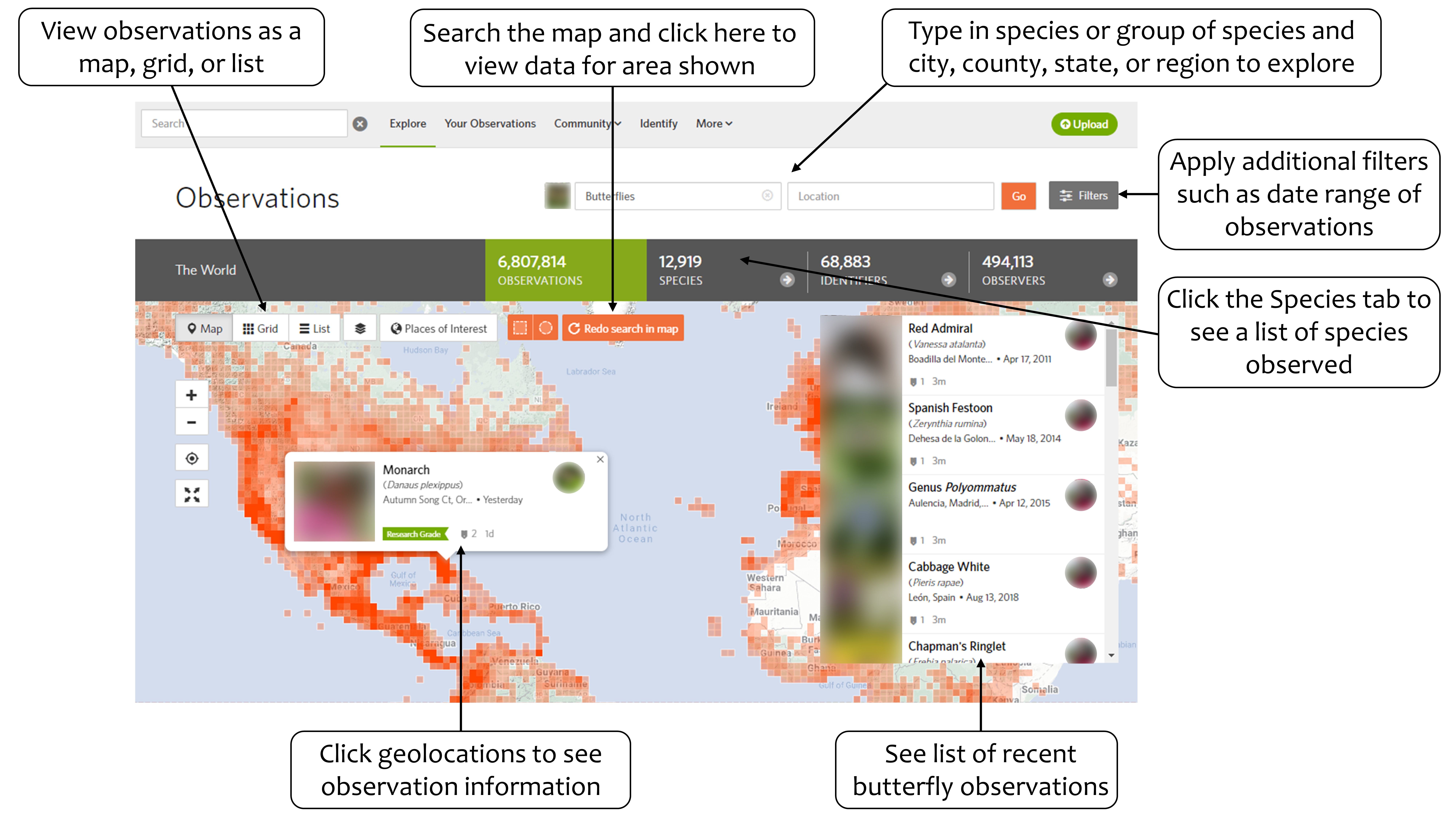

The iNaturalist website is an excellent resource to explore butterfly observations worldwide. The best way to explore butterfly species on iNaturalist is by filtering for them on the explore page. To see all the butterflies on iNaturalist, enter “butterflies” in the species field on the observations page. This page features an interactive map that can be filtered by location and butterfly species (Figure 8).

Website screenshot from iNaturalist.org

Filter the interactive map to your city using the location box and go to the “Species” tab next to “Observations” from the Explore page to see a list of butterfly species from your city (Figure 9). The species are arranged from most observed to least observed and can provide a general idea of which species are most common, although some biases may exist in the data. Learn more about each species by clicking on the species entry. This will direct you to the species’ information page, which contains a graph displaying what time of year a species is most likely to be observed and general information on the species from Wikipedia. The “Map” tab on this page displays an interactive map showing where this species has been observed.

Website screenshots from www.iNaturalist.org; Gulf fritillary photo by Mary Keim (CC BY-NC-SA)

Once you are familiar with butterfly identification, consider helping others identify their butterfly observations from the “identify page.” This page provides a grid view of observations and can be filtered the same as described above from the “Explore” page (see the identify page instructions in iNaturalist’s Getting Started folder for more information). Adding your own identifications is a great way to engage in the iNaturalist community and learn more about the butterfly species in your area. Additionally, identifications increase the value of observations for scientific use (see Callaghan et al. 2022 to learn more).

Conclusion

Butterflies live in a variety of habitats and thus provide an excellent opportunity to engage with biodiversity. Adding data and improving the quality of data on butterflies to platforms like iNaturalist is an engaging way to contribute to science. We encourage any butterfly enthusiasts to get out and find and document more butterflies!

Additional Resources

The Butterflies of America webpage shares a catalog of all butterfly species in North America.

The McGuire Center for Lepitoptera and Biodiversity contains a wealth of resources on butterflies.

The book Pollinators of Native Plants includes detailed information on pollinator gardening in North America.

Jaret Daniels’s book Your Florida Guide to Butterfly Gardening includes detailed information on butterfly gardening in Florida.

Florida Butterfly Encounters, available at the UF/IFAS bookstore, is a series of booklets that aims to engage both beginner and seasoned butterfly enthusiasts.

Butterflies and Moths of North America is a comprehensive resource with photos and information about butterflies.

eButterfly is an additional citizen science platform that is geared for serious butterfly enthusiasts.

References

Callaghan, Corey T., Thomas Mesaglio, John S. Ascher, et al. 2022. “The Benefits of Contributing to the Citizen Science Platform iNaturalist as an Identifier.” PLoS Biology 20 (11): e3001843. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001843.

Forister, Matthew L., Emma M. Pelton, and Scott H. Black. 2019. “Declines in Insect Abundance and Diversity: We Know Enough to Act Now.” Conservation Science and Practice 1 (8): e80. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.80

Mesaglio, Thomas, Aaron Soh, Steven Kurniawidjaja, and Chuck Sexton. 2021. “‘First Known Photographs of Living Specimens’: The Power of iNaturalist for Recording Rare Tropical Butterflies.” Journal of Insect Conservation 25:905–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-021-00350-7

Pickering, John, Dorothy Madamba, Tori Staples, and Rebecca Walcott. 2016. “Status of Moth Diversity and Taxonomy: A Comparison Between Africa and North America North of Mexico.” Southern Lepidopterists' News 38 (3): 241–48.

Pyrcz, Tomasz W., Pierre Boyer, Jean-Claude Petit, et al. 2024. “Bedazzled: A new, striking species of Corades from the outskirts of Quito questions our knowledge of Andean cloud forest butterflies (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae, Satyrinae).” Zootaxa 5453 (2):255–62. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5453.2.6

Scott, James A. 1992. The Butterflies of North America: A Natural History and Field Guide. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Warren, A. D., K. J. Davis, E. M. Stangeland, J. P. Pelham, K. R. Willmott, and N. V. Grishin. 2024. “Illustrated Lists of American Butterflies.” https://www.butterfliesofamerica.com