Overview

This EDIS publication is designed to provide an overview of the Targeting Outcomes of Programs (TOP) Model (Rockwell & Bennett, 2004) of program planning and evaluation, to define the levels for assessing program performance, and to identify evaluation strategies appropriate for measuring program performance at each level. Extension faculty may find this publication to be helpful when determining how to measure the performance of their educational programs.

What is the TOP Model?

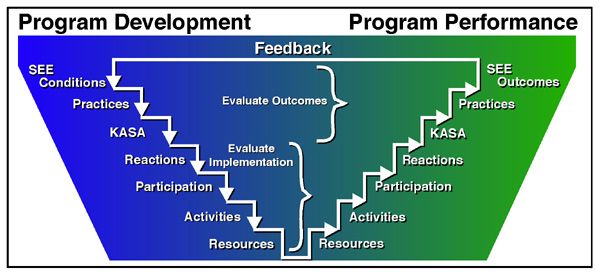

The TOP Model was developed in 1994 by Drs. Claude Bennett and Kay Rockwell. The foundation of the TOP Model is Bennett's (1975) hierarchy, a well-known model for evaluating program outcomes. The TOP Model encourages program planners to consider the outcomes they intend to achieve during each step of the planning process; thus, the program planning and program performance sides of the model are mirror images of each other (see Figure 1). It is this mirroring of planning and performance that separates the TOP Model from other commonly used program development models, such as the Logic Model.

Defining Program Performance Levels

The TOP Model contains seven levels (Rockwell & Bennet, 2004). The levels are presented vertically to indicate their increasingly complex nature.

For the purposes of this publication, exclusive attention will be paid to the program performance side of the TOP model. However, the definitions that follow may be applied to either program planning or program performance since the levels are the same on both sides of the model.

-

Resources—time, money, human capital (e.g., number of county faculty needed to facilitate program, number of volunteers needed at each activity), in-kind support from external organizations, donations

-

Activities—any educational session such as a class, workshop, seminar, field day, or consultation

-

Participation—involvement of learners and volunteers

-

Reactions—evidence of participant satisfaction and engagement

-

KASA—an acronym for the knowledge, attitudes, skills, and aspirations of participants

-

Practices—behaviors of the participants

-

SEE conditions—social, economic, and environmental conditions, such as family health, community income, or pollution levels

Identifying Evaluation Strategies

Two types of evaluation are used to determine program performance within the TOP Model. The process evaluation measures the resources used, activities held, participation, and participant reactions (Rockwell & Bennett 2004). Typically, these levels are the easiest parts of a program to evaluate. Results from a process evaluation provide valuable feedback for how to improve the mechanics of a program.

The outcomes evaluation measures changes in participant knowledge, attitudes, skills, and aspirations (KASA); participant behavior; and social, environmental, and economic outcomes (Rockwell & Bennett 2004). The outcomes evaluation focuses on measuring the immediate, medium, and long-term benefits of a program for individuals and communities; as a result, the outcomes evaluation is progressively more difficult to conduct than the process evaluation. This presents a challenge for Extension faculty because the greatest values of a program are the effects it has on changing practices and improving SEE conditions. Nearly any program can cause KASA changes, but good programs change practices and great programs positively affect SEE conditions.

Extension faculty can collect quantitative and qualitative data as indicators of program performance during process and outcome evaluations. Quantitative data is numeric (Gall, Gall, & Borg 2007). Qualitative data is typically verbal (Gall et al.). Although quantitative data are traditionally associated with program evaluation, using both types of data can be useful in developing a more comprehensive assessment of program performance. Some ideas for collecting quantitative and qualitative data to measure program performance at each level have been provided below.

Resources

-

Compare actual time expenditures vs. anticipated time expenditures

-

Compare actual costs vs. anticipated costs

-

Compare actual staff/volunteer FTE spent on the program vs. anticipated FTE

Activities

-

Report frequency, duration, and content of each program activity

-

Compare actual activities delivered vs. planned activities

Participation

-

Report attendance per activity

-

Keep records, not estimates

-

Report audience demographics (e.g. gender, race, ethnicity)

-

Did the target audience attend?

-

Report volunteer participation

-

Compare attendance by delivery strategy

-

Compare actual attendance vs. anticipated attendance

-

Compare actual volunteer participation vs. anticipated volunteer participation

Reactions

-

Use an exit survey to measure participants' interest in the program activities

-

Were the activities perceived to be fun, informative, interesting, or applicable? Boring, lengthy, or irrelevant?

-

Quantitative and qualitative questions are appropriate

-

Measure participants' engagement

-

Record observations such as number of individuals who contributed to discussion, participated actively in an activity, etc.

-

Consider using volunteers for this task

KASA

-

KASA changes may be measured immediately after a program ends

-

Measure increases in knowledge, changes in attitude, improved skills and abilities, and changes in aspirations

-

Quantitative: valid and reliable tests (knowledge and skill) and close-ended survey questions

-

Qualitative: open-ended survey questions, interviews, observations of skill

Practices

-

Practice changes may be measured after sufficient time has been given to participants to implement new behaviors; this will vary by behavior

-

Observe and record participant behavior after program completion

-

May want to use video or photography

-

Measure self-reported behaviors

-

Surveys, focus groups, or interviews

-

Compare actual percentage of participants adopting the new behavior with the anticipated percentage of adopters

SEE conditions

-

SEE condition changes may be measured after evaluation of practice changes

-

Measure benefits such as increased income, enhanced protection of fragile environments, decreased levels of incarceration, decreased levels of juvenile delinquency, decreased levels of unemployment, etc.

-

Use publicly available data (e.g., government reports) when possible

-

Partner with state Extension specialists or cooperating organizations for evaluation assistance; consider including an economist on the evaluation team

-

Conduct longitudinal studies (e.g., compare level of pollutants in watershed at regular intervals over a two year time span)

Conclusions

This EDIS publication provided an overview of the TOP Model (Rockwell & Bennett, 2004), defined the levels for assessing program performance, and identified evaluation strategies appropriate for measuring program performance. Extension faculty can use the TOP Model to develop an evaluation plan that carefully examines the educational process and program outcomes. The results obtained from conducting an evaluation using the TOP Model can be used for program improvement and to satisfy reporting and accountability expectations.

It should be noted that using the TOP Model to measure program performance does not guarantee that a program was the sole cause of any outcomes, only that there is a likely association between the program and the outcomes. This is generally sufficient for reporting purposes. Those wishing to learn about conducting more rigorous evaluations are encouraged to read "Phases of Data Analysis" (Israel 1992), "Sampling the Evidence of Extension Program Impact" (Israel 1992) or "Elaborating Program Impacts through Data Analysis" (Israel, 2006).

References

Bennett, C. (1975). Up the hierarchy. Journal of Extension, 13(2), 7-12.

Gall, M D., Gall, J. P., & Borg, W. R. (2007). Educational research: An introduction (8th ed.). USA: Pearson Education, Inc.

Israel, G. D. (2006). Elaborating program impacts through data analysis (2nd ed.). PD003. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pd003 (March 2016).

Israel, G. D. (1992). Phases of data analysis. PD001. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pd001 (March 2016).

Israel, G. D. (1992). Sampling the evidence of extension program impact. PD005. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pd005 (March 2016).

Rockwell, K., & Bennett, C. (2004). Targeting outcomes of programs: A hierarchy for targeting outcomes and evaluating their achievement. Faculty publications: Agricultural Leadership, Education & Communication Department. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/aglecfacpub/48/ (March 2016).