Encouraging Behavior Change Through Extension Programming

Extension "is reported to be one of the world's most successful change agencies" (Rogers, 2003, p. 391), and the ability to encourage behavior change remains critical to Extension programming accountability and ultimately to its success (Harder, 2012). Programs that result in increased knowledge without actual change in practice have been compared to programs that do not increase knowledge at all (Clements, 1999). Educational outreach activities must continually evolve to serve changing consumer behaviors and emerging technologies (Doerfert, 2011). However, change in general is highly complex, even at the individual level (Conroy & Allen, 2010). This article describes an approach to understanding how Extension audiences move through the process of change to improve the delivery of meaningful programming at the most appropriate level. This publication is intended for Extension professionals working in any discipline.

Educational programs should be "based on solid principles of behavior change" (Pratt & Bowman, 2008), and it is important to recognize that behavior change is something that happens over time (Shaw, 2010). A current focus among agricultural education research includes measures to increase our understanding of how audiences react to various programs, including the impact programs have on consumer behaviors (Doerfert, 2011). While we have many ways to look at how our programs impact our Extension clientele, evaluating behavioral change resulting from planned programs is a major challenge (Clements, 1999).

Many of the behaviors encouraged through Extension programming are complex changes that are not adopted immediately. However, this does not mean that a program has not affected the target audience (Clements, 1999). Changes in practices involve "moving through a range of stages, and each stage has its own requirements for institutional support" (Conroy & Allen, 2010, p. 196). The following example illustrates this range of stages.

Consider a time that you adopted something new, like a new smart technology for your home. Most likely, you did not hear about it the first day it was available. You were unaware of this new thing, but other people may have already installed it. At some point you heard about it, and you may have thought it sounded unnecessary. As time passed, you may have started to notice that some friends or coworkers had installed this technology and were having good results. At this point you might have started to think about trying it. At some point, you might have visited a store to prepare to try this technology. All of these stages may have led up to you taking action and purchasing and installing this new technology. After trying it, you might have continued using the technology for many years, maintaining it as a part of your life, or you may have decided it was not for you, and returned it or replaced it with something else.

Extension educational programming is based on a primary goal of bringing about individual behavior change (Boone et al., 2002), and it has been suggested that "our goal should be to begin to move our clientele from one stage of change to another in order to maximize program impact in terms of adoption of best practices" (Clements, 1999, Challenges for Extension Professionals, para. 11) even if this means reducing the number of programs conducted or clientele reached. This translates to a focus on more meaningful impacts. Extension professionals have the opportunity to better understand an audience's perceived barriers and benefits of making specific changes when they understand where someone is in the process of behavior change (Shaw, 2010). We can gain an understanding of Extension clients' progression using the concept of stages of change. This concept has proven to be useful in needs assessments and evaluation activities, and there are numerous models that characterize the change process.

Introduction to the Transtheoretical Model of Change

The Transtheoretical Model of Change (Norcross et al., 2011; Prochaska & Marcus, 1994), or TTM, is one of a number of useful interpretations of the stages of change. The TTM model portrays a clear picture of how people move gradually to the eventual adoption of some behavior. In the late 1970s, TTM was developed out of similarities among some major psychotherapy theories that were used to explain individual change processes (Norcross & Goldfried, 2005). TTM includes four major concepts that are summarized below: the process of change, the stages of change, and two indicators of success—confidence and decisional balance (Xiao & Wu, 2006).

The Process of Change

TTM is a valuable model for Extension because it not only defines the stages of change but also explains how change occurs (process of change). An understanding of how change occurs allows Extension professionals to match audiences with appropriate methods of messaging and supporting activities to encourage movement through to the next stage.

The Stages of Change

The stages of change are described in detail below. The amount of time Extension clients spend at one stage is variable and will be different from one person to the next (Norcross et al., 2011). We cannot predict how long an Extension client would spend in one stage, but we can identify the stage they are in and understand their needs based on the stage.

Indicators of Successful Behavior Change

The TTM offers two additional elements that are considered indicators of successful change: decisional balance and confidence (i.e., self-efficacy) (Xiao & Wu, 2006). Decisional balance refers to an individual's judgement as to whether the benefits of a practice change outweigh the costs of adoption (Xiao & Wu, 2006); in other words, that the change would be worthwhile. Confidence refers to how comfortable an individual is in adopting the new practice, or not engaging in a competing, less-desirable behavior (Xiao & Wu, 2006).

Understanding Stages as Defined by the Transtheoretical Model of Change

The five stages of change are known as Precontemplation, Contemplation, Preparation, Action, and Maintenance (Norcross & Goldfried, 2005; Shaw, 2010). These stages can be defined with respect to specific behaviors that occur when an individual is in a particular stage (Prochaska & Marcus, 1994). Another way to describe these stages is: not ready for change (precontemplation), getting ready for change (contemplation), ready for changing (preparation), changing (action), and continuing the change (maintenance).

Gutter et al. (2007) characterized these stages in terms of financial savings behavior. They represented these stages with respect to setting goals for savings, seeking information on savings, actively contributing to an account, and maintaining the savings program for at least six months.

It is important to note that movement through the stages is not necessarily linear, and individuals can regress to a previous stage or exit the process entirely at any time.

There are multiple processes that relate to progression toward behavior change. The following table adapted from Prochaska et al. (1997) places them in context of the stages of change and provides the definitions of these processes. These processes of change can help us to select appropriate Extension activities and teaching methods. One way to incorporate the stages of change is by developing activities to reach people at each stage within a major Extension program.

Identifying Stages of Change and Recruiting Based on These Stages

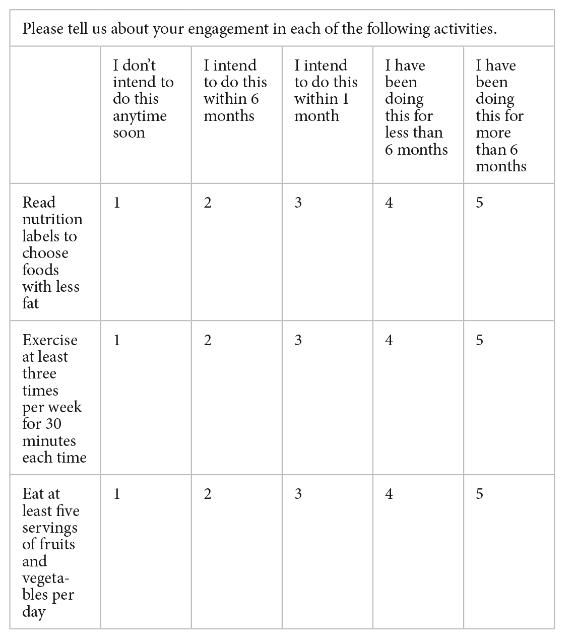

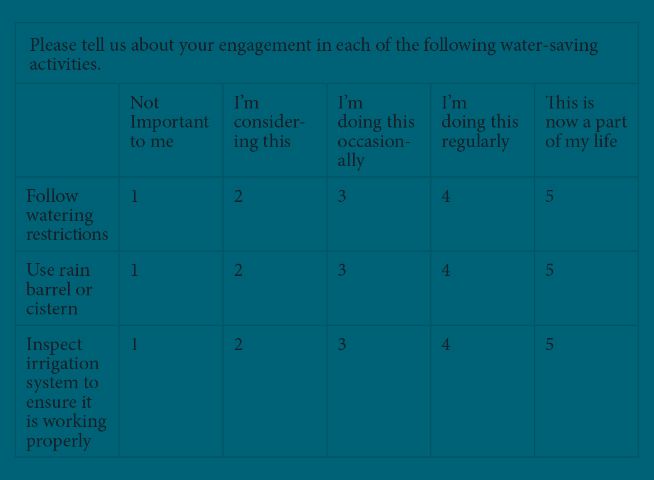

Identifying your target audience's stages of change is invaluable for tailoring your programs to match the audience's needs and helping them move to further stages of change. Each of the five stages of the TTM relates to a point in time in the life of an individual with regards to the adoption of, or the presence/absence of plans to adopt, a particular change within different time-frames (or, in other words, a continuum between Behavior Intention and Behavior Observed). Therefore, we need to collect data to capture the stage of change individuals are in with respect to the specific changes that we wish to promote in their lives. Figures 1 and 2 are examples of two Likert-type scales that can be used to help you establish at which stage of change your participants currently are. The labels for the scale points correspond to the five stages of change in the TTM (i.e., 1 = Precontemplation, 2 = Contemplation, 3 = Preparation, 4 = Action, and 5 = Maintenance).

Knowing your target audience's stage(s) of change empowers you to incorporate the most effective messages to encourage progression to the next stage and also to be more realistic in your expectations, and therefore the evaluation, for your program. Moving an audience from one stage to another is a great accomplishment that may be overlooked when evaluating a program based on complete adoption alone.

For example, if your audience is composed mostly of individuals at the precontemplation or contemplation stages, then you need to concentrate on providing as much information as possible on the proposed change(s), the reasons for changing, the risks of not changing, and the benefits of changing. The effectiveness of a program offered to an audience with these characteristics could then be evaluated in terms of observed changes in awareness, self-efficacy, knowledge, and attitudes of participants with respect to the proposed changes. On the other hand, if your audience is composed mostly of individuals who have already taken action or are in a maintenance stage, then you should not waste time providing information that they already know or trying to convince them of the need to change; you should focus your efforts on teaching them strategies to overcome the common challenges that may jeopardize their change process and helping them realize all the benefits that they have already achieved, and will be achieving soon, as a result of their decision to change.

In addition to tailoring the content and delivery of your existing programs, you may also develop new programs or direct individuals in your audience to other existing programs based on knowing where they are in the process of change. The strengths and limitations of your programs helping participants move through the stages of change will indicate what types of outcomes (e.g., changes in awareness, knowledge, skills, attitudes, aspirations, behavior, or practices, etc.) should result from participation in your programs. Your evaluation activities must concentrate on exploring those outcomes that can be plausibly connected with what your program can realistically achieve.

Using TTM to Communicate about Planned Programs and Resulting Outcomes

The use of TTM as a framework to evaluate and communicate the outcomes of a program brings a new dimension to both activities by placing emphasis not only on the outcomes but also on the context and process that led to them. In this case, the context refers to the characteristics of our audience, particularly in regards to their readiness to change, and the process considers the actions that we implemented (e.g., adapting program content and delivery) to give our audience the best chance to achieve positive outcomes as a result of their participation in our program.

Structuring communication/reporting activities in alignment with TTM allows you to logically and sequentially explain what you did, why you did it, what was feasible to expect from what you did, and the result of what you did. A structure like this makes it easier for readers and stakeholders to understand not only the activities that you conducted but also the rationale behind your activities and, more importantly, the cumulative contribution of your activities to promote maintained positive change.

Conclusion

As strategic behavior change begins during planning and needs assessment, it is important to determine ways to best serve an audience very early in the Extension programming process. This publication describes TTM and discusses its value in delivering meaningful programming based on a comprehensive understanding of a specific Extension audience. It is important to recognize the complex and staged nature of behavioral change, and Extension professionals may find TTM to be a valuable tool for planning and reporting.

References

Boone, E. J., Safrit, R. D., & Jones, L. (2002). Developing programs in adult education: A conceptual programming model (2nd ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Clements, J. (1999). Results? Behavior change! Journal of Extension [Online], 37(2), Article 2COM1. https://archives.joe.org/joe/1999april/comm1.php

Conroy, D. M., & Allen, W. (2010). Who do you think you are? An examination of how systems thinking can help social marketing support new identities and more sustainable living patterns. Australasian Marketing Journal, 18(3), 195–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2010.06.006

Doerfert, D. L. (Ed.) (2011). National research agenda: American Association for Agricultural Education's research priority areas for 2011–2015. Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University, Department of Agricultural Education and Communications.

Gutter, M. S., Hayhoe, C. & Wang, L. (2007). Examining participation behavior in defined contribution plans using the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change. Financial Counseling and Planning, 18(1), 46–60. https://www.afcpe.org/news-and-publications/journal-of-financial-counseling-and-planning/volume-18-1/examining-participation-behavior-in-defined-contribution-plans-using-the-transtheoretical-model-of-behavior-change/

Harder, A. (2012). Planned behavior change: An overview of the diffusion of innovations. (2nd ed.) (WC089). Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Retrieved from https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/wc089

Jayaratne, J. S. U., Hanula, G., & Crawley, C. (2005). A simple method to evaluate series-type Extension programs. Journal of Extension [Online], 43(2), Article 2TOT3. https://archives.joe.org/joe/2005april/tt3.php

Norcross, J. C., & Goldfried, M.R. (Eds). (2005). Handbook of psychotherapy integration (2nd ed.) New York: Oxford University Press.

Norcross, J. C., Krebs, P. M., & Prochaska, J. O. (2011). Stages of Change. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20758

Pratt, C., & Bowman, S. (2008). Principles of effective behavior change: Application to Extension family educational programming. Journal of Extension [Online], 46(5), Article 5FEA2. https://archives.joe.org/joe/2008october/a2.php

Prochaska, J. O., & Marcus, B. H. (1994). The transtheoretical model: applications to exercise. In R. K. Dishman (Ed), Advances in exercise adherence. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers.

Prochaska, J. O., Redding, C., & Evers, K. (1997). The Transtheoretical Model and stages of change. In K. Glanz, F. M. Lewis, and B. K. Rimer (Eds.), Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice (2nd Edition). Jossey-Bass Publications, Inc.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York: Free Press.

Shaw, B. (2010). Integrating temporally oriented social science models and audience segmentation to influence environmental behaviors. In L. Kahlor & P. Stout (Eds.), Communicating science: New agendas in communication. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Xiao, J. J., Newman, B. M., Prochaska, J. M., Leon, B., Bassett, R., & Johnson, J. L. (2004). Applying the transtheoretical model of change to consumer debt behavior. Financial Counseling and Planning, 15(2), 89–100. https://www.afcpe.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/vol1529.pdf

Xiao, J. J., & Wu, J. (2006). Applying the transtheoretical model of change to credit counseling: Addressing practical issues. Consumer Interest Annual, 55, 426–431. https://www.consumerinterests.org/assets/docs/CIA/CIA2006/xiaowu_applyingthetranstheoreticalmodelofchangetocreditcouns.pdf