Introduction

Researchers at the University of Florida estimate there are at least 76,000 stormwater ponds (SWPs) in the state and there may be as many as 100,000 currently (Sinclair et al., 2020). This number increases with each new land development project. This publication addresses some of the most frequent questions that residents ask regarding the function and maintenance of their ponds. It is designed to be a resource for people who live on or near SWPs, and for Extension professionals who work with these residents. Our team comprised of experts in urban ecology, stormwater engineering, and social science summarizes what we currently know about each topic.

What are stormwater wet ponds, and what do they do?

They are human-made, engineered bodies of water.

SWPs are a planned feature of built environments. They are designed to address the impacts of how structures such as buildings and roads affect the movement of water runoff across the landscape. There are two main types of stormwater ponds — dry ponds and wet ponds. Dry ponds collect water during storms but do not stay filled, as collected stormwater eventually percolates into the soil. Wet ponds, on the other hand, do stay filled. This document focuses on wet ponds (Figure 1), which are designed as permanent water bodies. People often mistake wet ponds for naturally occurring lakes. In reality, they are built, regulated, and maintained by humans.

Credit: Michelle Atkinson, 2021, UF/IFAS

If you are not sure if a body of water near you is a SWP, here are a few ways you can tell:

- Look for concrete or metal structures or pipes (Figure 1). These features usually mean that the pond is a SWP with a system to control overflow.

- Follow the gutters and storm drains in your street and see if they flow into the pond.

- If there is an aeration device like a fountain or subsurface bubbler, it is probably a SWP. Check out this Ask IFAS resource for more information on SWP aeration.

- In Florida, ponds in highly developed areas, including many neighborhoods with homeowners’ associations (HOAs), are usually engineered rather than naturally occurring.

- Many SWPs were built using permits, which may be accessible via your area’s water management district.

- Many SWPs are connected to larger water flow systems. A pond in your backyard may receive water from ponds further “upstream.” Then, the water likely flows “downstream” to someone else's neighborhood pond and eventually to a wetland, stream, river, or estuary.

They help control the flow of water, capture runoff, and recharge groundwater.

SWPs catch water that flows across lawns, roofs, roads, and other hard surfaces. Capturing this water helps reduce the risk of flooding. It also helps filter out the pollutants that accumulate on the landscape and are washed off with the surface runoff. Some ponds are also designed to recharge groundwater. We refer to these functions as the primary ecosystem services of SWPs because they are the intentional services provided by SWPs. In other words, these are the main benefits that SWPs are designed to provide to humans. As a bonus, many SWPs also provide secondary ecosystem services. These secondary benefits include providing habitat for wildlife (such as birds), adding visual interest to landscape views, or capturing and storing carbon.

Some developers capitalize on these secondary ecosystem services and make SWPs a central aesthetic feature of a community. This focus on secondary services can, however, create conflicts with the primary ecosystem services. These conflicts arise when decisions made for aesthetic reasons make SWPs less effective at controlling flooding and filtering out pollutants. There are several steps residents can take and/or advocate for to help keep SWPs healthy and functioning as best they can. These are discussed below.

What are effective strategies for pond maintenance?

Prevent problems before they occur.

Issues associated with SWPs, such as erosion of the shoreline and poor water quality, are very difficult and often costly to fix once they start. Even though SWPs are designed to collect sediments (e.g., soil, dirt) and pollutants (e.g., fertilizer, pet waste, motor oil) before they flow downstream, too much buildup causes problems. The combination of fertilizers, pet wastes, decaying plant matter, and reclaimed water used for irrigation contributes to nutrient buildup in ponds. Additionally, chemical runoff from motor oils, coolants, car wash soaps, and pesticides can affect the health of a pond and the wildlife living in it. Pressure-washing buildings and pointing gutter downspouts onto driveways can cause more of these chemicals to move into ponds. Downspouts can further add nutrients from leaf litter decaying in gutters and contribute to erosion problems because of the rapid flow of water toward the pond. If one or more of these issues occur around a pond, you can expect some problems such as erosion, excessive algal growth, or sedimentation (Figures 2 and 3).

Credit: Michelle Atkinson, 2021, UF/IFAS

Credit: Michelle Atkinson, 2018, UF/IFAS

Therefore, preventing problems with SWPs means reducing the amount of nutrients and chemicals that are introduced into the ecosystem, such as fertilizers, pesticides, and nutrient-rich reclaimed water. It also involves finding ways to slow down the flow of water, allowing more time for natural nutrient removal processes to occur along the flow path. Slowing down the water flow allows runoff to be partially filtered before flowing into ponds. Here are some specific preventive actions residents can take:

- Implement Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ practices by efficiently irrigating with only the necessary amount of water for your plants and/or by using plant species that require no fertilizer or irrigation once established.

- Ensure sprinklers do not spray irrigation water onto roads, driveways, or sidewalks. This increases both the amount of water that ends up in a stormwater pond and the amount of pollution running off these hard surfaces into stormwater ponds.

- If you use reclaimed water for irrigation, use less fertilizer or consider stopping fertilizer use entirely. Reclaimed water is already high in the same nutrients that fertilizers contain (Lusk & Rainey, 2021).

- Minimize your use of pesticides and herbicides. Also refrain from using fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides before a rainstorm. Always follow local fertilizer ordinances.

- Consistently pick up pet waste and encourage your neighbors to do the same.

- Promptly clean up oil spills, coolant leaks, and other chemical deposits on driveways and other hard surfaces. Dispose of these chemicals by removing them from the environment.

- Keep grass clippings, dead leaves, and other plant matter away from ponds and storm drains because these plant materials can decompose and add nutrients to ponds (Figure 4) (Lusk, 2023).

- Regularly remove leaf litter from the gutters on your home. Direct downspouts away from paved surfaces such as driveways. Instead, let the downspouts drain onto your lawn or flower beds. This will help to irrigate your landscape and allow pollutants to percolate into the ground rather than flowing directly into storm drains.

- Add ground cover (such as turfgrass, mulch, or alternative plant ground coverings) to any spots of bare soil to reduce erosion (Figure 5).

- Install a rain garden to catch and filter some of the water before it flows into the pond. For more information on rain gardens, consult this UF/IFAS Extension Hillsborough County resource.

- Learn about Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ for more tips on maintaining a healthy and beautiful landscape while protecting Florida’s natural resources.

Credit: Michelle Atkinson, 2022, UF/IFAS

Credit: Michelle Atkinson, 2019, UF/IFAS

Install plants — ideally native plants — around the pond to prevent erosion.

Bank erosion is an especially hard and expensive problem to fix. Even in small ponds, wind causes waves that can erode sediments from the bank, transporting them from the bank to the bottom of the pond. Stormwater ponds are designed to maintain a certain storage volume of water, and SWPs with erosion problems fill in more quickly and require more frequent dredging. They can also develop steep slopes that can be dangerous — even fatal — for people working or playing near the pond. Additionally, when SWPs are near homes, erosion can reduce residents’ yard space.

Plants around ponds help prevent erosion in two key ways. First, plants in the littoral zone — the shallow area where the waterline meets the shoreline — help reduce the impact of waves. Figures 6 and 7 show how plants installed in a littoral zone contribute to maintaining the pond’s health and appearance. Second, plants’ root systems hold onto the soil and make it less likely to fall into the pond. These two functions make pond plantings a great choice for preventing erosion. Watch this video from UF/IFAS Extension Manatee County to see how littoral plantings help break the waves. In addition, planting native plants densely may hinder the re-establishment of problematic invasive plant species which have been previously removed (Enloe et al., 2022). Invasive species are those plants introduced by humans that can cause environmental, economic, or human harm (Iannone et al., 2021). See this resource and this publication for help in selecting the right native plant species for your pond.

Credit: Michelle Atkinson, 2020, UF/IFAS

Credit: Michelle Atkinson, 2020, UF/IFAS

Here are a few tips for choosing pond plants:

- Keep in mind that the pond landscape has three different zones: the upper bank, the littoral (shallow water) zone, and the aquatic (deeper water) zone. Plants need to be installed in all three, and they need to be chosen specifically for each zone.

- Use Florida-Friendly plant species, especially those that are native to Florida (Figure 8). Never use invasive plants, which can overgrow, quickly spread to areas where they are not wanted, and have lasting environmental and economic impacts. For example, invasive aquatic plants that cover most of the water’s surface can decrease views of the pond or hinder recreational access. They can also cause negative impacts to Florida’s aquatic ecosystem. The UF/IFAS Assessment, the Green Stormwater Infrastructure Guidebook, and the Florida-Friendly Landscaping Plant Guide are resources that can be used to determine if a particular non-native plant species poses an environmental threat in Florida. Again, the resources listed above can help you choose the best species for your project.

Credit: Michelle Atkinson, 2021, UF/IFAS

- Use a mixture of plants that will be visually pleasing throughout the year, keeping in mind the seasonal cycles of the species you choose.

- Use a variety of plant species. The adage “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket” is good advice when choosing pond plants. When all the plants around a pond are the same species, a pest or disease that affects that species can destroy all the plants, potentially causing a complete loss in the benefits that the plants were providing (such as keeping soil from the bank in place). When you plant a variety of different species, those plants unaffected by the pests or disease can help to maintain desired functions and benefits.

- Install plants at a reasonably high density. The more plants that surround a pond, the less risk of erosion problems. Filling the available space with native plants also helps prevent unwanted, invasive species from establishing and taking over your pond. Additionally, when planting a pond, you should expect that some of the plants will not survive. Therefore, starting with higher-density planting will help keep it from becoming too sparse over time.

Check regularly to ensure the water flow is not blocked by sediments or debris.

The pipes and drains leading into and out of SWPs are essential for flood control. They must be repaired if they are damaged, and any buildup of leaves, sediments, or other debris must be cleared away (Figure 9). Over time, soil and other small particles collect on the bottom of SWPs. This is normal. In fact, one of the functions of SWPs is to keep these particles from flowing downstream and entering streams, rivers, and estuaries. Sometimes, sediments may need to be removed if they have filled in too much of the pond. This process is called dredging. Ideally, ponds should only need dredging every 20–30 years.

Credit: Michelle Atkinson, 2022, UF/IFAS

Keep learning about the latest research findings on best management practices.

There is still much we do not know about what works to keep ponds functional and healthy. For example, SWPs are intended to remove 80 percent of pollutants such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediments in stormwater and prevent them from flowing downstream. However, results from a report by Harper and Baker (2007) showed that they are not even close to meeting this standard for nitrogen. There are many pollutants that SWPs do not effectively remove. Additionally, we are discovering that ponds can actually produce nutrients rather than just collect them. Therefore, there is a chance that a pond’s natural processes might be increasing or contributing to nutrient levels more than was originally assumed (Hohman et al., 2021; Reisinger et al., 2020). We therefore need to keep investigating ways to better manage stormwater. In the meantime, we must use the best available strategies for preventing pollution from entering the ponds in the first place. Each pond is unique, so a strategy that works well for one pond or community may not be the best choice elsewhere. Interdisciplinary teams of University of Florida researchers are working to understand how to tailor strategies to different kinds of SWPs.

In addition, residents have different opinions about what is aesthetically pleasing and may not understand what a well-functioning pond looks like. What homeowners want and expect from their landscape views may not match with the best practices for pond maintenance. That is why we need to learn how to improve communication among residents, property managers, pond management companies, and landscapers. Ecologists, engineers, economists, and social scientists are working together to bring new insights about how to address these complex challenges to the public. For example, we have learned that while homes on SWPs may be marketed as “lakefront,” SWPs are clearly not natural lakes, and due to their primary functions, can look quite different. Therefore, it is important to inform prospective buyers about the ecological functions of SWPs and how to evaluate whether they are well managed.

What does it mean when a pond has algae?

The influx of nutrients from the landscape into the stormwater pond fuels the growth of algae, which is a normal process. Not all algae are bad. However, excessive algae growth (Figure 10) can lead to water quality issues and is aesthetically unappealing. Homeowners often perceive algae within ponds as an environmental nuisance. Overgrowth of algae (known as “blooms”) and other aquatic plants can indeed indicate some ecological issues. Therefore, if you have an algal bloom in your pond (Figure 11), you may need to have it addressed by a professional. Algal blooms can cause various ecological, economic, and social impacts including fewer wildlife within a pond, reduced satisfaction with pond aesthetics, and even potential negative health impacts associated with harmful algal blooms (Huisman et al., 2018).

Credit: Michelle Atkinson, 2021, UF/IFAS

Credit: Michelle Atkinson, 2022, UF/IFAS

Despite this potential for negative impacts, algae are a natural part of ponds and can take up nutrients from lawn fertilizer, grass clippings, and reclaimed water (Figure 12). By absorbing nutrients from the surrounding environment, algae slow down the movement of pollutants to streams and rivers, making the pond more environmentally beneficial. Additionally, many aquatic organisms rely on algae as a food resource. Therefore, the adage “All things in moderation” is a good rule of thumb for understanding if algae is overgrown and whether you need to consult with a pond management professional. For more information on algae management strategies in your SWP, consult this UF/IFAS resource.

Credit: Michelle Atkinson, 2021, UF/IFAS

What are the benefits of preventing issues in stormwater pond systems?

Save money in the long run.

A key benefit of preventing erosion is avoiding a large bill to restore the shoreline. A general estimate of the cost to fix an eroded pond bank is around $100 per linear foot. Even though planting ponds costs money up front, it should pay off in erosion prevention over time if done correctly. Buffer zones, sometimes referred to as no-mow zones, are vegetated lands that can be natural or human-made, serving to shield a water body from adverse human activities. As such, buffer zones play an essential role in safeguarding shorelines against erosions. A good buffer typically features a grass strip at least 3 feet in width and 10 to 15 inches in height. The effectiveness of a buffer zone is also influenced by the diversity of plants and trees planted in and around the pond, and the width of the buffer (US EPA, 2021). Also, taking steps to better manage nutrients in the landscape can reduce the need to spray chemicals on ponds for algae bloom control. These steps can be as simple as keeping grass clippings out of the pond, picking up pet waste consistently, and reducing or even eliminating fertilizer use. In addition to making your local pond healthier, better nutrient management reduces the pollution that flows downstream to the natural water bodies that are so important to Florida’s environment and economy.

Enjoy viewing plant and animal life in your community.

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Generally, preventive maintenance can have aesthetic benefits for those who live on or visit SWPs. Denser and more varied plant life provides habitat to animals that many people enjoy seeing, such as birds, fish, and turtles. Certain plants, especially those that flower, also enhance the aesthetic value of a pond. Additionally, plants in the littoral zone (the shallow area near the shoreline) often hide some of the algae that inevitably grow in SWPs. These benefits may improve property values for nearby homes.

Protect the water quality in nearby streams, rivers, and estuaries.

Florida’s natural waters benefit residents and visitors alike. To keep enjoying these benefits, we need to reduce the amount of pollutants flowing into ponds and enhance the ability of ponds to remove these pollutants that otherwise impact downstream water bodies, such as streams, rivers, and estuaries. Polluting these water bodies may affect the safety of swimming, fishing, and other popular activities in rivers, lakes, and bays, which our state economy depends on for food, drinking water, recreation, tourism, and much more.

How can I tell if my pond is working properly?

Monitor water levels after a storm.

In general, the water level in a SWP should return to its regular level within a few days after heavy rain. If it seems as though water is not flowing out of a pond or is draining too slowly, check the outflow structure for blockages or debris. The pond should not overflow, or cause flooding in nearby structures during a regular storm event. If it does, this is a clear sign of a problem.

Work with a professional to monitor the rate of erosion.

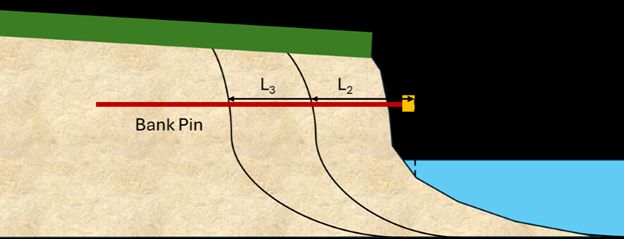

To check how fast a pond’s shoreline is eroding, work with a pond or landscape manager to develop a monitoring plan. One option you can suggest is using bank pins or soil erosion pins (Figure 13). Bank pins are sections of rebar that are driven horizontally into the bank, leaving a few inches sticking out. Periodically, measurements are taken by noting the date and recording how far the bank has receded relative to the exposed portion of the pin. Remeasuring the rod regularly and using the distance and the amount of time that has passed will give an estimation of the rate of erosion.

Credit: Eban Bean, 2024, UF/IFAS

Make sure the monitoring plan is carefully considered and implemented with the help of a professional. Because different areas of the pond may have different erosion rates, it is a good idea to place rods at multiple points around the pond. When choosing bank pin locations, be sure to locate them in areas that will not impede mowing or other foot traffic, or clearly mark the pins so that they are visible. Adding a cap to the bank pin will also signify its importance. It is essential to proceed with caution during pin placement to prevent any damage to existing infrastructure. Additionally, keep in mind that erosion can happen underneath turf, so eroded sections of the shoreline may not always be visible.

Assess the degree of bank slope.

Well-designed ponds without major erosion issues should have a smooth, gradual slope from the bank into the pond. A steeper slope is often a sign of an erosion issue. Not only will this be an expensive problem to fix, but it is also a safety and liability risk. Some ponds are designed with steep banks, which poses a challenge for planting vegetation and makes a less effective strategy for bank stabilization. Also, steep banks can make it hard for children and older adults to exit the pond if they were to fall in, potentially creating a liability. In addition, mowers on a steep slope (< 4:1) that get too close to the edge can roll over into the pond and injure or pin the driver.

Check if trash, grass clippings, and other debris are building up in the pond.

Trash floating in and around a pond is an obvious form of pollution. However, what many people may not know is that excessive amounts of plant and animal materials can also contribute to pollution levels in SWPs. The accumulation and decay of things like grass clippings, dead leaves, and pet waste adds nutrients to SWPs. These additional nutrients further strain the ability of SWPs to filter the water before it moves into natural water bodies. A moderate amount of fallen leaves in a pond is normal, but if it becomes excessive it may be necessary to clear some away to avoid degrading the water quality. Any trash should be removed immediately.

Have the water tested by a professional if you have a specific concern.

SWPs are designed to capture and filter runoff, so they are expected to contain a variety of pollutants as described earlier. However, excessive amounts can cause a variety of problems, such as algal blooms or low oxygen levels that harm fish. There is no single test for poor water quality because there are many factors affecting overall pond health. You also cannot always tell if a pond has poor water quality just by looking at it. For example, water that looks very clean and clear may contain so many pollutants that no animals or plants can survive in it. That is why it is important to consult a licensed pond management professional or your local Extension agent if there is a specific problem you want to address. Also, if a pond is used for irrigation or fishing, water should be tested regularly, especially if people consume the fish they catch.

Here are a few examples of issues that could be a sign of water quality problems:

A little bit of algae is normal and is a good thing because it helps to remove nutrients (pollutants) from the water and is essential for pond life. However, algae blooms that spread across the entire water surface (or below the surface) can mean that there are too many nutrients in the pond. When the pond has more nutrients than other plants and animals can use, these excess nutrients can allow algae to become overgrown. To investigate an issue with algae blooms, a pond management professional may test the water’s levels of chlorophyll, nitrogen, and phosphorus. There are chemical treatments that a licensed professional can apply in carefully managed amounts if needed.

Pond surfaces can also be covered by duckweed (Lemna spp.). There are five different species of duckweed in Florida. These aquatic native plants can cause similar benefits and concerns as algae, but they may need to be managed using different approaches.

- Fish kills can happen naturally due to heavy rains, rapid temperature drops, or other weather patterns. However, fish kills may also be a sign of a preventable issue such as low oxygen levels. There are methods to help prevent low oxygen levels by using mechanical aeration such as fountains for shallower ponds or bubblers for deeper ponds.

Murky water is normal after a storm. The murkiness is caused by suspended sediments that are transported from the landscape by the storm as well as sediments stirred up from the pond bottom as stormwater mixes with the pond. However, water that looks like chocolate milk or coffee with cream (Figure 14) for more than a few days after a storm can be a sign of a problem.

Credit: Michelle Atkinson, 2022, UF/IFAS

What are the costs to properly maintain a pond?

It depends on the pond, specifically its age and the amount of water it receives upstream.

Pond management is not a one-size-fits-all situation. The specific issues that might need to be addressed will vary according to multiple factors. For example, some ponds receive water from ponds further upstream. Poor water quality in those upstream ponds can cause issues in downstream ponds. Ponds of different sizes, ages, and locations will also have different challenges. Another important factor is the choices that the developer made during construction. If they did not use best management practices such as installing plants to prevent erosion, they pass the cost burden of fixing later issues on to the residents.

In general, taking preventive measures may be costly upfront but can save money over time. The good news is that there may be grant programs and other funding sources to help offset the costs. Sources to consider include estuary programs, native plant society chapters, county or city governments, water management districts, and statewide water quality improvement grants.

Who is responsible for pond function?

If the pond is permitted, the permit holder must keep the pond functioning.

In many situations, stormwater ponds owned by homeowner associations are considered common areas. In this case, the homeowner association takes care of getting the permits. In other instances, the property owner or manager is the one who holds the permit. After construction, keeping the pond working includes repairing damaged structures and dredging the pond if necessary. The permit holder (e.g., HOA, property owner, manager) is liable for any permit violations. This question is more complicated for ponds that do not have permits. In these cases, more effort may be needed to organize neighbors and ensure everyone is on the same page when addressing problems.

Several different parties should work together to manage and maintain ponds.

The actions of developers, residents, property managers, landscapers, and pond management companies all affect how SWPs function. All the pond professionals and landscapers who work around the pond should coordinate efforts and troubleshoot problems; without regular communication, one party can accidentally undo the efforts of another. Listen to this story about the importance of communication among residents, pond professionals, and landscapers.

Where can I find out more?

Pond Buffer Zone Best Management Practices Guide

Florida’s Water Permitting Portal

Florida-Friendly LandscapingTM Program

Sources and Transformations of Nitrogen in Urban Landscapes

A New Database on Trait-Based Selection of Stormwater Pond Plants

UF/IFAS Extension pond publications

Fact sheet: Best Management Practices for Blue-Green Algal Blooms in Ponds

Fact sheet: Buffer Zones for Stormwater Ponds

Postcard: Healthy Pond Banks & Buffer Zones

Fact sheet: Stormwater Ponds

Scorecard: Buffer Zone Scorecard

Scorecard: Littoral Zone Scorecard

Acknowledgments

The development of this publication was supported by awards from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (Agreement No. NS094) and the National Science Foundation (Award: DEB-2206234).

References

Enloe, S. F., Langeland, K., Ferrell, J., Sellers, B., & MacDonald, G. (2022). Integrated Management of Invasive Plants in Natural Areas of Florida. SP 242. EDIS. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/WG209

Harper, H. H., & Baker, D. M. (2007). Evaluation of Current Stormwater Design Criteria within the State of Florida. Florida Department of Environmental Protection. http://www.erd.org/ERD%20Publications/EVAL%20OF%20CURRENT%20SW%20DESIGN%20CRITERIA%20WITHIN%20THE%20STATE%20OF%20FLA-2007.pdf

Hohman, S. P., Smyth, A. R., Bean, E. Z., & Reisinger, A. J. (2021). Internal nitrogen dynamics in stormwater pond sediments are influenced by pond age and inorganic nitrogen availability. Biogeochemistry, 156, 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-021-00843-2

Huisman, J., Codd, G. A., Paerl, H. W., Ibelings, B. W., Verspagen, J. M. H., & Visser, P. M. (2018). Cyanobacterial Blooms. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 16(8), 471–483. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0040-1

Iannone, B. V. III, Bell, E. C., Carnevale, S., Hill, J. E., McConnell, J., Main, M., Enloe, S. F., Johnson, S. A., Cuda, J. P., Baker, S. M., & Andreu, M. (2021). Standardized Invasive Species Terminology for Effective Outreach Education: FOR370. EDIS. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-fr439-2021

Lusk, M. (2023). How to Manage Yard Wastes to Protect Surface Water Resources: SL509. EDIS. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-SS722-2023

Lusk, M. G., & Rainey, D. (2021). Best Management Practices for Irrigating Lawns and Urban Green Spaces with Reclaimed Water: SL491. EDIS. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-SS704-2021

Reisinger, A. J., Lusk, M. G., & Smyth, A. R. (2020). Sources and Transformations of Nitrogen in Urban Landscapes: SL468. EDIS. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ss681-2020

Sinclair, J. S., Reisinger, A. J., Bean, E. Z., Adams, C. R., Reisinger, L. S., & Iannone, B. V. III. (2020). Stormwater ponds: An overlooked but plentiful urban designer ecosystem provides invasive plant habitat in a subtropical region (Florida, USA). Science of the Total Environment, 711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135133

United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). (2021). Riparian Forest Buffer. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-11/bmp-riparian-forested-buffer.pdf