Introduction

The second publication in the Intercultural Competencies series provides insights and recommendations on engaging individuals from various backgrounds by understanding and applying value orientation theory.

Florida's agricultural landscape reflects its multicultural population (Ashiq, 2024; Florida Farm Bureau, 2022). The variety of agricultural practices, from citrus groves in the central region to vegetable fields in the south, reflects the unique contributions of different cultural groups (Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, n.d.; McCormick, 2018). However, this multiculturality also poses challenges for Extension professionals aiming to serve these communities effectively, as each cultural group brings its own agricultural methods and crop preferences (Diaz et al., 2019; Diaz et al., 2022). The agricultural practices in Florida are influenced by these cultural differences, with some groups favoring traditional organic methods passed down through generations, while others adopt advanced technological solutions (Agnoleti & Santoro, 2022; Nan et al., 2021). Therefore, Extension educators should develop intercultural competencies, particularly in understanding the cultural values that inform agricultural practices (Diaz et al., 2022).

Cross-cultural psychology provides a valuable framework for examining the interaction between individual behavior and cultural context (Berry, 2013; Keith, 2019). While universal physiological and psychological processes underlie human behavior, cultural variations shape how these processes manifest in everyday life and agricultural practices (Shiraev & Levy, 2020; Wei et al., 2020). By grasping both the universal and culturally specific aspects of human experience, Extension professionals can create more effective programs that resonate with varied farming communities to foster trust and bridge cultural divides (Diaz et al., 2022).

Understanding the cultural nuances influencing agricultural practices is crucial for successful Extension programming (Diaz et al., 2022). Value orientation theory offers a valuable framework for exploring these cultural differences. Extension professionals can tailor their programs by examining cultural values to better meet the needs of Florida's farming communities (Gallagher, 2001). This article examines the implications of value orientation theory for Extension work in Florida agriculture, providing practical recommendations for developing intercultural competence and program effectiveness.

This discussion describes the importance of Extension professionals, including district and county directors, integrating training on cultural value orientations into their professional development plans and program design. Doing so will enhance their effectiveness in supporting Florida's agricultural communities.

Value Orientation Theory

Value orientation theory, developed by Florence Kluckhohn and Fred Strodtbeck in the 1960s, postulates that all human societies must answer a limited number of universal questions related to human existence (Hills, 2002; Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck, 1961; Schwartz, 2014). These answers reflect cultural values, which influence agricultural practices and interactions. Below is a checklist highlighting key cultural orientations and providing practical methods for Extension professionals to detect and interpret them.

- Human Nature Orientation: How do humans perceive their inherent nature?

- Detection:

- People express optimism or skepticism about others' intentions.

- There is an emphasis on trust and cooperation or caution and the need for oversight.

- Responsibilities are shared freely or with reluctance due to concerns about trust.

- Detection:

- Human-Nature Relationship Orientation: What is the perceived relationship between humans and nature?

- Detection:

- Farming practices focus on working with nature (organic, natural methods).

- There is a stronger focus on controlling nature through technology, chemicals, or machinery.

- Discussions include an emphasis on environmental conservation or technological advancements.

- Detection:

- Time Orientation: How do cultures perceive and value time?

- Detection:

- Traditions and past practices are frequently referenced in conversations.

- Present-day problems and short-term solutions are prioritized, or long-term benefits are planned for.

- There is a strong attachment to preserving heritage or a greater focus on innovation.

- Detection:

- Activity Orientation: What is the preferred mode of human activity?

- Detection:

- Immediate action and achieving tangible outcomes are prioritized.

- Discussions are reflective and oriented toward long-term planning or theoretical understanding.

- There is visible urgency to get things done, or participants take time to deliberate and reflect.

- Detection:

- Relational Orientation: How do cultures structure their social relationships?

- Detection:

- Decisions are typically made by individuals in authority, such as elders or community leaders.

- Deference to hierarchical structures is visible in meetings or discussions.

- Collaboration and equality are emphasized, with all voices heard equally in group settings.

- Detection:

These orientations shape worldviews, interactions, and decision-making processes. Thus, Extension educators need to recognize and adapt to these cultural differences when working with diverse communities.

Human Nature Orientation

This orientation concerns how different cultures view the fundamental nature of human beings. Cultures may perceive people as inherently good, inherently evil, or both. This perception influences trust levels, societal rules, and interpersonal dynamics within a community.

Inherently Good

Cultures that view human nature as fundamentally sound emphasize trust, mutual respect, and collaborative efforts. Individuals are seen as capable of positively contributing to society (Sheng, 2023).

How to Detect

- If community members are generally open, cooperative, and quick to help one another without suspicion or hesitation, it may suggest a belief in the inherent goodness of people.

- Listen for sayings such as "People here always have each other's back," which reflects trust and a positive view of human nature.

- In cases of mistakes or noncompliance, notice if the response is more forgiving and focuses on understanding rather than punishment.

Example

In specific rural communities in Florida, particularly among small-scale organic farmers, there is a sense of mutual trust and cooperation. These farmers share knowledge and resources freely, supporting each other in developing sustainable practices without stringent oversight. An Extension educator in this setting could introduce community-led workshops on organic farming techniques, trusting that participants will collaborate and support the initiative for the collective good.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- Cooperative Agricultural Communities: These groups focus on mutual support and collaboration in farming, trusting neighbors to contribute positively to the community.

- Faith-Based Agricultural Groups: Rooted in compassion and charity, these groups believe in people's inherent goodness and engage in community-driven projects.

Inherently Evil

In contrast, cultures that view humans as inherently evil might prioritize strict regulations, accountability, and control mechanisms to ensure compliance and order within the community (Putra et al., 2021).

How to Detect

- People might be more guarded, less likely to share personal information, and more focused on protecting their own interests.

- Common sayings such as "Trust but verify" or "You cannot be too careful" might indicate a belief that people are not inherently trustworthy.

- Strict rules, punitive measures for noncompliance, and a focus on control might suggest a belief in the inherent evil of people.

Example

In more urbanized areas of Florida, where large-scale commercial farming occurs, there may be stricter regulations and oversight due to concerns about compliance with environmental standards. Here, an Extension educator might focus on implementing strict monitoring systems for pesticide usage, requiring regular inspections, and emphasizing compliance to avoid penalties, reflecting a more cautious view of human behavior.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- Heavily Regulated Farming Operations: Large agricultural businesses that emphasize strict rules and oversight to prevent unethical behavior.

- Communities with High Crime/Mistrust: Urban areas with higher crime where personal protection and mistrust reflect a belief in the need for control.

Mixed View

Cultures that perceive human nature as a mix of good and evil may advocate for balanced approaches, combining trust with necessary oversight (Hao et al., 2016).

How to Detect

- Mixed signals, such as openness in some contexts but caution in others, may indicate a belief that human nature is neither good nor bad.

- Sayings like "People mean well, but..." might indicate a balanced view of human nature.

- Look for a combination of collaborative approaches and accountability measures, suggesting a belief that people need guidance but are capable of good.

Example

In Florida’s water management districts, communities often strike a balance between trust and regulation, particularly concerning water usage for agriculture. An Extension educator might work with these communities to promote sustainable water use through collaborative workshops and structured oversight, such as periodic reviews to ensure compliance with water conservation goals.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- Extension-Based Community Initiatives: Communities balancing trust in human potential with structured oversight through agricultural projects.

- Local Government Programs: County agricultural initiatives that mix optimism with accountability to ensure program success.

Human-Nature Relationship Orientation

This orientation explores how different cultures view the relationship between humans and nature. It addresses whether humans are subordinate to nature, in harmony with nature, or dominant over nature (Duong et al., 2019).

Subjugation to Nature

Subjugation is bringing someone or something under domination or control, often by force. It involves the imposition of authority and power over others, typically leading to their submission and loss of freedom (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). Cultures that believe in subjugation to nature may see natural forces as powerful and uncontrollable, requiring humans to adapt and live in harmony with nature’s will (Hills, 2002).

How to Detect

- Observe if the community relies on traditional, low-intervention farming methods that align with natural cycles.

- Nature is often depicted as a powerful force in art, music, or rituals, with humans shown adapting to it.

- Community members may express respect for nature, believing in living in harmony rather than trying to control it.

Example

In coastal Florida communities, especially those reliant on traditional fishing methods, there is often a deep respect for the ocean's unpredictability. An Extension educator working in such a community might promote fishing practices that respect natural cycles, such as seasonal closures to protect fish stocks, emphasizing the need to adapt to nature rather than control it.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- Indigenous and Seminole Communities: Emphasize respect for nature’s power, following traditional, sustainable practices.

- Environmental Conservationists: Advocate for minimal human interference, focusing on nature preservation (e.g., the Everglades).

Harmony with Nature

Cultures respect the environment, seek harmony with nature, advocate for sustainable practices, and seek a balance between human needs and environmental preservation (Hills, 2002).

How to Detect

- Look for sustainable practices that aim to maintain ecological balance, such as crop rotation, composting, and natural pest control.

- Nature might be portrayed as a partner or equal in cultural expressions, indicating a balanced relationship.

- Support for environmental initiatives and a focus on preserving natural resources for future generations suggest a harmony-oriented view.

Example

Floridian Native American tribes, such as the Seminole and Miccosukee, often emphasize a more harmonious relationship with nature. Their traditional practices include sustainable hunting, fishing, and harvesting, reflecting a deep respect for the environment and its natural cycles. An Extension educator might introduce organic farming practices in a community that values harmony with nature. The educator could run workshops on composting, crop rotation, and integrated pest management, highlighting how these methods maintain ecological balance and reduce the environmental impact of farming.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- Sustainable Agriculture Advocates: Use organic farming techniques to maintain balance with nature.

- Eco-Friendly Tourism Groups: Promote responsible tourism that preserves Florida’s natural resources.

Dominion over Nature

Cultures that believe humans have dominion over nature may focus on technological advancements and exploiting natural resources to improve human living standards (Hills, 2002).

How to Detect

- Practices that focus on maximizing yield and efficiency, even if they involve significant manipulation of the environment, indicate a belief in dominion over nature.

- Nature may be depicted as something to be conquered or controlled, rather than something to live in harmony with.

- Conservation might be seen as secondary to economic growth, with a focus on exploiting natural resources for human benefit.

Example

In parts of Florida, large-scale agriculture and technological innovation drive farming practices, such as in the Everglades Agricultural Area, where there is a focus on maximizing crop yields through technological advancements. An Extension educator in this setting might promote precision agriculture, using data analytics and advanced irrigation systems to control natural resources and boost efficiency, reflecting a dominion-oriented approach to nature.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- Coastal Developers: Real estate developers who prioritize human needs over nature, modifying environments like wetlands for construction.

- Large-Scale Agricultural Producers: Industrial farms that prioritize human control over nature through the substitution of environmentally protected areas for large-scale agricultural production.

Time Orientation

Time orientation refers to how cultures perceive and value time. It emphasizes the past, present, or future in decision-making and planning (Lee et al., 2017).

Past-Oriented

Cultures that emphasize the past may value traditions, history, and ancestral wisdom. Decision-making is often influenced by historical experiences and continuity with past practices (Kim et al., 2022).

How to Detect

- Listen for frequent references to historical events, ancestors, or traditional practices during conversations.

- Observe if there is a firm adherence to customs and rituals, with changes often being resisted.

- Phrases such as "This is how we have always done it" or "We honor the ways of our ancestors" can indicate a past-oriented perspective.

Example

In Florida’s rural communities, especially among older generations of farmers or Indigenous groups, there may be a strong emphasis on traditional agricultural practices passed down through generations. An Extension educator might introduce new crop varieties by drawing connections to these traditional crops, respecting the community’s past-oriented values while promoting agricultural innovation.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- Traditional Florida Farmers: Emphasize historical agricultural practices, valuing long-standing methods passed through generations.

- Indigenous Groups: Prioritize ancestral wisdom and traditional practices, resisting changes that deviate from historical norms.

Present-Oriented

Cultures that focus on the present may prioritize immediate needs and experiences over long-term planning or historical considerations (Gallagher, 2001).

How to Detect

- Decision-making tends to prioritize immediate benefits or solutions over long-term planning.

- Community members may emphasize living in the moment or addressing current challenges rather than focusing on future outcomes.

- Look for a "live for today" attitude, focusing on short-term results or solutions.

Example

A present-oriented mindset often prevails in communities affected by immediate challenges, such as frequent hurricanes. Extension educators in Florida might focus on quick, practical solutions to address current needs, such as emergency preparedness workshops and fast-acting recovery strategies, rather than emphasizing long-term mitigation measures.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- Hurricane-Impacted Communities: Focus on immediate relief and recovery, addressing urgent needs rather than long-term planning.

- Seasonal Immigrant Farmworkers: Often move based on crop cycles and immediate job opportunities.

Future-Oriented

Cultures that are future-oriented value long-term planning, innovation, and progress. They are likelier to adopt new technologies and ideas that promise future benefits (Pawlak & Moustafa, 2023).

How to Detect

- Observe if the community engages in long-term planning focusing on future goals and aspirations.

- Conversations may frequently revolve around progress, innovation, and ways that current actions will impact the future.

- Sayings like "Investing in the future” or "We need to plan for tomorrow" indicate a future-oriented perspective.

Example

Florida’s research-driven agricultural hubs, particularly around the University of Florida, strongly emphasize future-oriented, AI-driven agriculture. Extension educators play a key role in promoting the adoption of climate-resilient crops and advanced technologies that secure the long-term sustainability of local agriculture. By encouraging innovation and strategic planning, educators help integrate artificial intelligence into production systems to ensure the community is well-prepared for future agricultural challenges.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- University of Florida Research Hubs: Embrace innovation and long-term strategies, focusing on advanced agricultural technologies and climate resilience.

- Tech Startups: Prioritize future advancements and technological progress, planning for long-term impact.

Activity Orientation

This orientation explores the preferred activity mode within a culture, focusing on the balance between action, contemplation, and being (Hills, 2002; Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck, 1961).

Being Orientation

Cultures that prioritize "being" value personal growth, inner reflection, and living in harmony with one’s surroundings. There is less emphasis on achieving specific goals or altering the environment.

How to Detect

- People may express contentment with life, valuing personal relationships and inner peace over material success.

- Conversations might focus on the quality of life, well-being, and enjoyment of the present moment rather than goals or achievements.

- Phrases like "It is about the journey, not the destination" or "We value peace and balance" suggest a being-oriented mindset.

Example

In specific retirement communities in Florida, the focus may often be on quality of life and personal well-being rather than productivity. For an Extension educator working with these communities on projects like community gardens, it would be important to emphasize the mental health benefits of gardening, framing the activity to promote relaxation and inner peace rather than stressing high productivity. During these sessions, the educator could also create opportunities for open discussion, allowing participants to share their experiences and be fully present in the moment, and fostering a deeper sense of connection and engagement.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- Retirement Communities: Focus on quality of life and personal well-being, emphasizing relaxation and inner peace.

- Mindfulness and Wellness Groups: Prioritize self-reflection and living harmoniously with one’s surroundings.

Doing Orientation

In contrast, cultures with a "doing" orientation value achievement, productivity, and actively shaping one’s environment. There is a strong emphasis on setting and accomplishing goals.

How to Detect

- People may frequently discuss their goals, achievements, and the steps they are taking to reach them.

- The community might be highly organized, focusing on efficiency and progress, with less tolerance for inactivity or delays.

- Common phrases might include "Let’s get it done" or "Time is money," reflecting a focus on action and productivity.

Example

Florida’s highly productive agricultural zones, such as those focusing on citrus and strawberry production, prioritize efficiency and results. An Extension educator might set clear productivity goals for a new agricultural initiative, such as increasing crop yields through advanced irrigation or pest control methods, reflecting the community’s goal-oriented approach.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- High-Productivity Agricultural Zones: Emphasize efficiency and productivity in crop production, such as in citrus or strawberry farms.

- Business Hubs: Focus on achieving goals and enhancing productivity, emphasizing action and results.

Being-in-Becoming Orientation

Cultures with a "being-in-becoming" orientation value self-improvement, focusing on developing oneself through actions that align with inner values and potential.

How to Detect

- Conversations may revolve around self-improvement, personal growth, and becoming a better version of oneself.

- The community might support activities that promote self-reflection and personal development, such as educational workshops or meditation sessions.

- Sayings like "Always striving to be better" or "Growth is a lifelong journey" indicate a being-in-becoming orientation.

Example

An Extension educator could focus on leadership development programs in communities that support self-improvement and personal growth, such as specific urban development projects in Florida. For example, they might promote workshops encouraging participants to set personal growth goals in communication and decision-making, aligning with the community’s focus on continual self-improvement.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- Personal Development Workshops: Focus on self-improvement and personal growth through various activities.

- Urban Development Projects: Emphasize continuous personal development and aligning actions with inner values.

Relational Orientation

Relational orientation focuses on how individuals relate to others within their social structure, including hierarchy levels, authority, and collectivism versus individualism (Hills, 2002; Schwartz, 2014).

Individualism

Cultures that value individualism emphasize personal autonomy, independence, and self-reliance. Individuals are encouraged to pursue their goals and express their unique identities (Hills, 2002; Schwartz, 2014).

How to Detect

- People may prioritize their own goals and achievements over group interests.

- There may be a focus on personal responsibility, with less emphasis on communal or family obligations.

- Common phrases such as "Stand on your own two feet" or "Be true to yourself" reflect a focus on personal autonomy.

Example

In entrepreneurial hubs such as Miami, there is often an emphasis on individual success and innovation. An Extension educator might offer programs encouraging personal entrepreneurship, such as workshops on starting a small agribusiness, emphasizing self-reliance and innovation. Regardless of the specific program type, the focus should consistently highlight the benefits that will directly return to the individual. Whether in business, education, or community initiatives, ensuring participants see the personal rewards of their involvement is essential to the program’s success.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- Miami Entrepreneurial Hubs: Emphasize personal autonomy and individual success in business and innovation.

- Freelancers and Gig Economy Workers: Emphasize autonomy and self-management.

Collectivism

In contrast, collectivist cultures prioritize group harmony, cooperation, and interdependence. Individuals are often expected to prioritize group goals over personal desires (Hills, 2002; Schwartz, 2014).

How to Detect

- People may prioritize the needs and goals of the group over individual desires.

- There may be a strong emphasis on family and community obligations, with decisions often made collectively.

- Phrases like "We are all in this together" or "The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few" indicate a collectivist mindset.

Example

In Florida’s close-knit rural farming communities, there is often a stronger focus on collectivism, emphasizing cooperation and communal success. An Extension educator might facilitate group-based initiatives, such as cooperative farming projects, where the community’s success is prioritized over individual achievements. In these programs, the educator should highlight the impact of collective efforts, demonstrating how the strength and success of the whole community can outweigh individual contributions, and fostering a more profound sense of unity and shared accomplishment.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- Rural Farming Communities: Focus on cooperation and communal success, strongly emphasizing collective efforts.

- Community Cooperatives: Prioritize group harmony and shared goals, working together for mutual benefit.

Hierarchy

Cultures with a hierarchical orientation value authority, social status, and structured relationships. This orientation could be found in both individualistic and collectivistic cultures. Decision-making often follows established lines of authority (Hills, 2002; Schwartz, 2014; Warner et al., 2024).

How to Detect

- There may be a clear social structure, with respect and deference shown to those in positions of authority.

- Decision-making processes often involve consultation with or approval from senior figures or leaders.

- Phrases like "Know your place” or "Respect your elders" suggest a hierarchical orientation.

Example

In more traditional agricultural communities, where family farms often follow generational hierarchies, such as in parts of north Florida, an Extension educator might need to work through established lines of authority. Programs could be introduced by first gaining the trust and approval of community leaders or heads of farming families to ensure success.

Groups That May Align with This Orientation

- Traditional Agricultural Families: Follow generational hierarchies and respect established authority in family-run farms.

- Military Organizations: Follow strict hierarchical structures and respect for authority.

Recommendations for Extension Professionals

Conduct Cultural Assessments

Before designing or implementing any program, take the time to understand the community's cultural values. This can involve interviews, focus groups, and participation in community events to gain insight into the dominant cultural orientations.

Example

An Extension professional working in a rural community with a strong tradition of subsistence farming first conducts interviews with local farmers and participates in their communal events. Through these assessments, the professional learns that the community values self-sufficiency and deeply respects ancestral farming practices. With this understanding, the Extension professional designs a program that integrates modern farming techniques with traditional methods, ensuring that the innovation aligns with the community’s cultural values.

Resources Available to Conduct Cultural Assessments

Applying Culturally Relevant Teaching to Workshops — The Checklist

Culturally Responsive Teaching: A Framework for Educating Diverse Audiences

Build Trust through Cultural Sensitivity

Demonstrate respect for the community’s values by incorporating them into program design and delivery. This builds trust and increases the likelihood of program acceptance and success.

Example

An Extension professional introducing organic pest control methods to a community that traditionally relies on chemical pesticides employs the principles of community-based social marketing (CBSM) to foster behavior change. CBSM emphasizes listening to community members and analyzing behavior change to reduce barriers and increase perceived benefits (McKenzie-Mohr & Smith, 1999; Thomson & Brain, 2016). The professional identifies the community’s concerns and values through conversations with local farmers and stakeholders. By understanding their hesitation to shift from chemical to organic pesticides, the Extension professional tailors the intervention to address specific barriers, such as crop yield and cost concerns.

The Extension professional then introduces testimonials from respected local farmers who successfully adopted organic pest control, using CBSM’s emphasis on social norms to reinforce the credibility of the new practices. The program also incorporates hands-on workshops where participants can see the results of the organic methods firsthand, reducing skepticism and fostering a sense of ownership. Through CBSM’s approach, the professional respects the community’s knowledge and ensures that the behavior change is made easier and more appealing by aligning it with the community’s values and reducing barriers to adoption.

For more information on CBSM and its applications in Extension, see relevant Ask IFAS publications like Using Community-Based Social Marketing to Improve Energy Equity Programs (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/WC407).

Fostering Participation

Actively involve community members by ensuring that programs are not only accessible but also tailored to the needs of people from all cultural backgrounds. This can be achieved by offering programs that accommodate varying schedules, providing materials in multiple languages, and using different instructional methods to account for all learning preferences. Such efforts help bridge cultural divides and foster social cohesion within the community.

Example

An Extension program introduces a new drought-resistant crop variety. Aiming to ensure widespread engagement and success, the Extension professional schedules workshops at different times to accommodate the work schedules of farmers, provides materials in the primary languages spoken in the community, and uses a mix of hands-on demonstrations, group discussions, and visual aids to cater to various learning styles. The program also makes efforts to engage women, youth, and underrepresented groups, such as Indigenous groups, who may have been excluded from agricultural decision-making in the past. By encouraging broad participation, the program increases the adoption of the new crop and strengthens social bonds among community members who work toward a shared goal.

Engage with Community Leaders

Working with local leaders is vital in all communities, whether individualistic, collectivistic, or hierarchical. Engaging with these leaders helps you conduct a community assessment to better understand the community’s broader value orientations, cultural priorities, and social dynamics. By securing the leaders' support and input, you can design programs that resonate with the community’s values and increase the likelihood that the wider population will accept and support your initiative.

Example

An Extension professional seeks community leaders’ endorsement before introducing a new livestock management practice in a community where elders and local leaders hold significant influence. By engaging the leaders early, explaining the benefits of the practice, and incorporating their feedback, the Extension professional gains insight into the community’s priorities and values. With the leaders’ approval, the broader community is more likely to embrace innovation, knowing that it aligns with collective interests and has the backing of trusted authorities.

Discussion

Understanding the interplay of culture, social norms, and individual behaviors bridges cultural divides and tailors Extension programs to Florida's diverse agricultural communities. This section explores how these factors, as identified through an interdisciplinary literature review and bibliometric analysis, relate to the practical application of value orientation theory in Extension work.

A bibliometric analysis is a quantitative method used to evaluate academic literature by examining publication trends, citation networks, and keyword co-occurrence patterns (van Eck & Waltman, 2014). This approach helps identify the most influential research, emerging themes, and the relationships between key concepts in a particular field (Donthu et al., 2021). By systematically mapping scholarly discussions, bibliometric analysis offers a data-driven perspective on how different cultural dimensions intersect with Extension practices (Donthu et al., 2021; van Eck & Waltman, 2014).

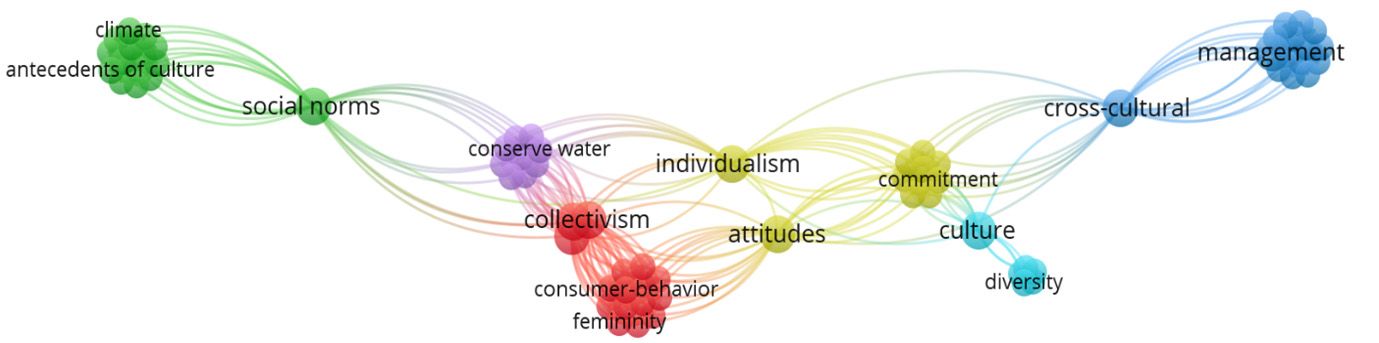

Using VOSviewer (version 1.6.20) to analyze keyword patterns from 20 interdisciplinary articles on culture, social norms, and behaviors identified in the Web of Science Core Collection (van Eck & Waltman, 2023), we gain actionable insights into the connections between these concepts, particularly within the context of intercultural competencies and value orientation theory. This analysis reveals that societal norms governing acceptable behavior, influenced by individual interactions and cultural antecedents, significantly impact agricultural practices and the adoption of Extension programs. There are different types of societies, each establishing social norms governing acceptable and unacceptable behavior based on individual interactions. The antecedents of culture refer to a leader's traits or preexisting cultural experience when making decisions (Kim et al., 2022). Social initiatives to conserve water, protect rural heritage, and promote biological diversity should align with cultural practices to help prevent potential dangers (Agnoletti & Rotherham, 2015; de Pasquale et al., 2020; Hernandez Marentes et al., 2022; Hoffman & Henn, 2008; Howard-Grenville & Hoffman, 2003; Warner et al., 2024). It is the primary responsibility of Extension educators and researchers to effectively communicate scientific information about social interventions related to climate change (Hoffman, 2010).

Individualism and collectivism dynamics are crucial to identifying attitudes, behavior, and social norms. Cho et al. (2013) examine the horizontal collectivism and vertical individualism of two cultures and conclude that pro-environmental attitudes become behavior based on perceptions of consumer effectiveness. Horizontal collectivism refers to a cultural orientation where individuals perceive themselves as part of a group, emphasizing equality and shared goals without hierarchical distinctions. This approach values collaboration and mutual support among group members. Conversely, vertical individualism describes a cultural orientation that emphasizes individual achievement and independence while accepting hierarchical relationships and competition within the group (Albarracin et al., 2018; Singelis et al., 1995).

Understanding of gender plays a significant role in shaping culture. The concept of femininity encompasses traits associated with women and girls, such as cooperation, compassion, and nurturing (Chwialkowska et al., 2020). Pro-environmental attributes and behavior create a constant feedback loop between humans and ecology. Femininity is a way to understand gender-related practices in agriculture (Brown, 2004).

Cultural variety is an asset in cross-cultural interactions (Adler & Aycan, 2018). Extension educators serve as the bridge to reach single or multiple cultures and develop communication strategies with various cultural groups in Florida.

Conclusion

Understanding cultural value orientations is crucial for Extension professionals working within Florida's diverse agricultural landscape. By recognizing and adapting to various cultural perspectives, Extension educators can design and implement programs that resonate with community values and beliefs, which ultimately lead to more effective and sustainable outcomes.

To further emphasize the importance of value orientation theory, we analyzed the term with a co-occurrence network, which revealed a dynamic interplay between cultural, social, and behavioral concepts, reinforcing the theory’s relevance in navigating Florida’s agricultural diversity. As a primary bibliometric finding, co-occurrence networks enhance relatable abstract concepts, demonstrating how understanding cultural nuances can highlight the practical importance of aligning educational efforts with communities' diverse perspectives and needs. The prominent clusters — collectivism, individualism, social norms, and attitudes — underscore the central role that cultural values play in shaping both agricultural practices and consumer behavior. For instance, commitment and conserving water reflect ecological concerns and collective cultural responses to environmental management. These align with the human-nature relationship orientation in value orientation theory, which guides how communities perceive and engage with conservation efforts.

Furthermore, the connections between culture, diversity, and cross-cultural management highlight the critical need for tailored agricultural programs that align with Florida’s multicultural farming communities. Cultural antecedents such as social norms, consumer behavior, and understanding of gender significantly shape agricultural decision-making. By acknowledging these influences, Extension professionals can create more culturally sensitive, inclusive, and effective programming that meets the unique needs of each community.

The figure below shows the network visualization illustrating the relationships between keywords found in 20 interdisciplinary articles on culture, social norms, and behaviors, indexed in the Web of Science Core Collection. It is designed to visually represent how frequently these keywords appear in the same articles, suggesting conceptual connections and research themes.

Credit: Pablo Lamino, John Diaz, Laura Valencia, and Jaehyun Ahn, UF/IFAS

Key Elements and Interpretation

Nodes (Circles): Each circle represents a keyword found in the analyzed articles.

Size: The size of a node indicates the frequency of the keyword's occurrence. Larger nodes mean the keyword appears more often.

Color: The color of a node often represents a cluster or group of related keywords. Nodes with similar colors are likely to be found together in the same articles, suggesting they represent a common theme or area of research.

Links (Lines): The lines connecting the nodes represent the co-occurrence of keywords.

Thickness: Thicker lines indicate a stronger relationship, meaning the keywords appear together more frequently.

Distance: The closer two nodes are, the more related they are. VOSviewer uses algorithms to position nodes based on their connection strength.

Clusters (Groups): The figure shows distinct clusters of nodes, each with a dominant color. These clusters represent themes or groups of related concepts.

Specific Observations from the Figure

Left Cluster (Green)

Contains "climate," "antecedents of culture," and "social norms."

Suggests research exploring the relationship between climate, cultural origins, and societal rules.

Center-Left Cluster (Purple/Red)

Includes "conserve water," "collectivism," "consumer behavior," and "femininity."

Indicates research themes related to environmental conservation behaviors, particularly in the context of collective societies and potentially gender-related influences.

Center Cluster (Yellow)

Features "individualism," "attitudes," "commitment," and "culture."

Points to studies examining individualistic perspectives, their impact on attitudes and commitments, and broader cultural analyses.

Right Cluster (Blue)

Consists of "management," "cross-cultural," and "diversity."

Represents research focused on management practices in diverse, cross-cultural settings.

Interpretation

The figure suggests that the research articles analyzed cover various interdisciplinary topics related to culture, social norms, and behaviors. The clustering of keywords reveals key themes, such as the influence of culture on environmental behaviors, the role of individualism and collectivism, and the challenges of cross-cultural management.

References

Adler, N. J., & Aycan, Z. (2018). Cross-Cultural Interaction: What We Know and What We Need to Know. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 307–333. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104528

Agnoletti, M., & Rotherham, I. D. (2015). Landscape and Biocultural Diversity. Biodiversity and Conservation, 24(13), 3155–3165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-015-1003-8

Agnoletti, M., & Santoro, A. (2022). Agricultural Heritage Systems and Agrobiodiversity. Biodiversity and Conservation, 31(10), 2231–2241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-022-02460-3

Albarracin, D., Jones, C. R., Hepler, J., & Li, H. (2018). Liking for Action and the Vertical/Horizontal Dimension of Culture in Nineteen Nations: Valuing Equality over Hierarchy Promotes Positivity Towards Action. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7176319/

Ashiq, H. A. (2024, August 6). Exploring Florida’s Farming Communities: Agriculture in the Sunshine State. Discover Real Food in Texas. https://discover.texasrealfood.com/state-soil-stories/farming-communities-in-florida#google_vignette

Batson, C. D., & Ahmad, N. Y. (2009). Using Empathy to Improve Intergroup Attitudes and Relations. Social Issues and Policy Review, 3(1), 141–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2009.01013.x

Berry, J. W. (2013). Cross-Cultural Psychology [Dataset]. In Oxford Bibliographies Online Datasets. https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199828340-0111

Brown, E. H. (2004). Technology, Culture, and the Body in Modern America. American Quarterly, 56(2), 449–460. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2004.0016

Cho, Y.-N., Thyroff, A., Rapert, M. I., Park, S.-Y., & Lee, H. J. (2013). To Be or Not to Be Green: Exploring Individualism and Collectivism as Antecedents of Environmental Behavior. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1052–1059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.020

Chwialkowska, A., Bhatti, W. A., & Glowik, M. (2020). The Influence of Cultural Values on Pro-Environmental Behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 268, 122305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122305

de Pasquale, G., & Spinelli, E. (2022). The Alpine Rural Landscape as a Cultural Reserve: The Case Study of Teglio in Valtellina. Biodiversity and Conservation, 31(10), 2397–2420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-021-02298-1

Diaz, J., Gusto, C., Silvert, C., Jayaratne, K. S. U., Narine, L., Couch, S., Wille, C., Brown, N., Aguilar, C., Pizaña, D., Parker, K., Coon, G., Nesbitt, M., Valencia, L., Ledesma, D., & Fabregas, L. (2022). Intercultural Competence in Extension Education: Applications of an Expert-Developed Model: AEC760/WC421, 9/2022. EDIS, 2022(5). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-wc421-2022

Diaz, J., Suarez, C., & Valencia, L. (2019). Culturally Responsive Teaching: A Framework for Educating Diverse Audiences: AEC678/WC341, 10/2019. EDIS, 2019(5). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-wc341-2019

Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., & Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 133, 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

Duong, N. T. B., & Van Den Born, R. J. G. (2019). Thinking about Nature in the East: An Empirical Investigation of Visions of Nature in Vietnam. Ecopsychology, 11(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0051

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. (n.d.-a). Florida Agriculture Overview and Statistics. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. https://www.fdacs.gov/Agriculture-Industry/Florida-Agriculture-Overview-and-Statistics

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. (n.d.-b). Agricultural Best Management Practices. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. https://www.fdacs.gov/Agriculture-Industry/Water/Agricultural-Best-Management-Practices

Florida Farm Bureau. (2024, March 12). 2022 Census Data Available Now. Florida Farm Bureau. https://floridafarmbureau.org/news/2022-census-of-agriculture-available-now/

Gallagher, T. (2001). The Value Orientations Method: A Tool to Help Understand Cultural Differences. Journal of Extension, 39(6). https://archives.joe.org/joe/2001december/tt1.php

Hao, J., Li, D., Peng, L., Peng, S., & Torelli, C. J. (2016). Advancing Our Understanding of Culture Mixing. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 47(10), 1257–1267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022116670514

Hernandez Marentes, M. A., Venturi, M., Scaramuzzi, S., Focacci, M., & Santoro, A. (2022). Traditional Forest-Related Knowledge and Agrobiodiversity Preservation: The Case of the Chagras in the Indigenous Reserve of Monochoa (Colombia). Biodiversity and Conservation, 31(10), 2243–2258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-021-02263-y

Hills, M. D. (2002). Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck's Values Orientation Theory. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 4(4). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1040

Hoffman, A. J. (2010). Climate Change as a Cultural and Behavioral Issue: Addressing Barriers and Implementing Solutions. Organizational Dynamics, 39(4), 295–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2010.07.005

Hoffman, A. J., & Henn, R. (2008). Overcoming the Social and Psychological Barriers to Green Building. Organization & Environment, 21(4), 390–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026608326129

Howard-Grenville, J. A., & Hoffman, A. J. (2003). The Importance of Cultural Framing to the Success of Social Initiatives in Business. Academy of Management Perspectives, 17(2), 70–86. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2003.10025199

Keith, K. D. (Ed.). (2019). Cross-Cultural Psychology: Contemporary Themes and Perspectives (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Kim, Y. J., Toh, S. M., & Baik, S. (2022). Culture Creation and Change: Making Sense of the Past to Inform Future Research Agendas. Journal of Management, 48(6), 1503–1547. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063221081031

Kluckhohn, F. R., & Strodtbeck, F. L. (1961). Variations in Value Orientations. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson.

Lee, S., Liu, M., & Hu, M. (2017). Relationship between Future Time Orientation and Item Nonresponse on Subjective Probability Questions: A Cross-Cultural Analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(5), 698–717. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117698572

McCormick, K. (2018, March 21). Rediscovering Florida’s Rich Agricultural Heritage. UF/IFAS Extension Seminole County. https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/seminoleco/2018/03/20/floridas-rich-agricultural-heritage/

McKenzie-Mohr, D., & Smith, W. (1999). Fostering Sustainable Behavior: An Introduction to Community-Based Social Marketing. Gabriola Island, B.C.: New Society.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Subjugation. In Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved September 3, 2024, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/subjugation

Nan, M., Lun, Y., Qingwen, M., Keyu, B., & Wenhua, L. (2021). The Significance of Traditional Culture for Agricultural Biodiversity — Experiences from GIAHS. Journal of Resources and Ecology, 12(4). https://doi.org/10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2021.04.003

Pawlak, S., & Moustafa, A. A. (2023). A Systematic Review of the Impact of Future-Oriented Thinking on Academic Outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1190546

Putra, I. E., Campbell-Obaid, M., & Suwartono, C. (2021). Beliefs about human nature as good versus evil influence intergroup attitudes and values. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 27(4), 576–587. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000469

Schwartz, S. H. (2014). National Culture as Value Orientations: Consequences of Value Differences and Cultural Distance. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture (pp. 547–586). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-444-53776-8.00020-9

Sheng, H. (2023). Why is human nature good? Advances in Anthropology, 13(02), 69–94. https://doi.org/10.4236/aa.2023.132005

Shiraev, E., & Levy, D. A. (2020). Cross-Cultural Psychology: Critical Thinking and Contemporary Applications (7th ed.). Routledge.

Singelis, T. M., Triandis, H. C., Bhawuk, D. P. S., & Gelfand, M. J. (1995). Horizontal and Vertical Dimensions of Individualism and Collectivism: A Theoretical and Measurement Refinement. Cross-Cultural Research, 29(3), 240–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/106939719502900302

Stofer, K. A. (2017). Education and Facilitation Methods for Extension: AEC619/WC281, 4/2017. EDIS, 2017(2). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-wc281-2017

Suarez, C. E., Diaz, J. M., & Valencia, L. E. (2020). Applying Culturally Relevant Teaching to Workshops — The Checklist: AEC688/WC351, 1/2020. EDIS, 2020(1). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-wc351-2020

Thomson, I., & Brain, R. (2016). A Primer in Community-Based Social Marketing. Cache Valley Transit District and Utah State Extension Service. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2664&context=extension_curall

Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2014). Visualizing bibliometric networks. In Y. Ding, R. Rousseau, & D. Wolfram (Eds.), Measuring scholarly impact: Methods and practice (pp. 285–320). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10377-8_13

Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2023). VOSviewer Manual: Manual for VOSviewer version 1.6.20. Retrieved from https://www.vosviewer.com/documentation/Manual_VOSviewer_1.6.19.pdf

Warner, L. A., Diaz, J. M., Kalauni, D., & Yazdanpanah, M. (2024). Encouraging Others to Save Water: Using Definitions of the Self to Elucidate a Social Behavior in Florida, USA. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption, 12, 100176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clrc.2024.100176

Wei, Y., Spencer-Rodgers, J., Anderson, E., & Peng, K. (2020). The Effects of a Cross-Cultural Psychology Course on Perceived Intercultural Competence. Teaching of Psychology, 48(3), 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628320977273