Introduction

Cucurbit downy mildew is a major disease that affects all cucurbits. Commercially important species of cucurbits include watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), muskmelon (Cucumis melo), cucumber (Cucumis sativa), squash (Cucurbita pepo, Cucurbita moschata), and pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima). The causal agent is the fungal-like organism (oomycete), Pseudoperonospora cubensis (Sitterly 1992).

Symptoms and Signs

The classic sign of the disease is the presence of dark sporangia on the underside of infected leaves (Figures 1 and 5). Symptoms of cucurbit downy mildew are characterized by foliar lesions, which first appear as small chlorotic patches on the upper side of the leaves (Figures 2 and 3). Lesions may appear water-soaked, especially during periods of prolonged leaf wetness caused by rainfall, dew, or irrigation. As the disease progresses, these lesions may coalesce into large necrotic areas and result in defoliation and a reduction of yield and marketable fruit (McGrath et al. 2008) (Figure 4).

What is a sporangia?

A sporangium (pl. sporangia) is a structure that holds spores as they are being developed. This is the main source of inoculum into a new field. It is common to see several sporangia on a structure called a sporangiophore.

What is a sporangiophore?

A sporangiophore is a specialized hyphal structure that holds multiple sporangia.

Credit: M. Paret

Credit: M. Paret

Credit: M. Paret

Credit: M. Paret

Epidemiology and Disease Cycle

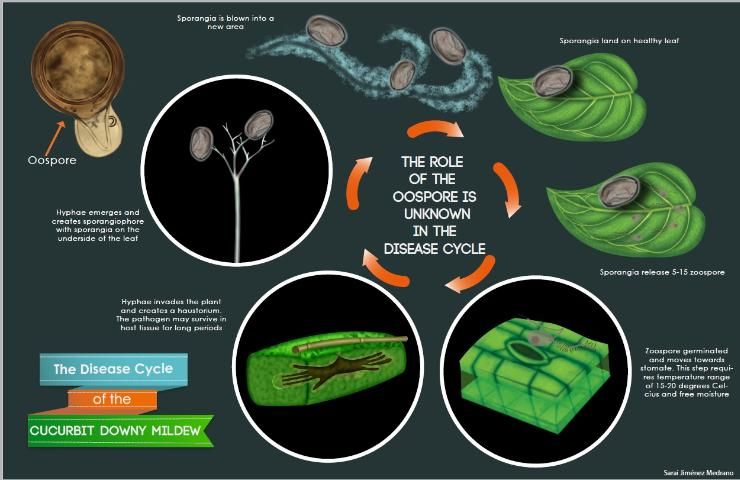

Cucurbit downy mildew is caused by a biotrophic organism or obligate parasite, which means it needs a living host to survive. The overwintering structure, the oospore, has not been observed in the United States, and the pathogen does not survive on crop debris between seasons. P. cubensis must be reintroduced each year. The sporangia are dispersed by wind and serve as the primary source of inoculum (Figure 5). They require free water for germination, which occurs rapidly at 15 to 20°C (59–68°F). Secondary inoculum within an infected field is dispersed by rain-splash and/or wind dispersion.

Credit: N. Dufault

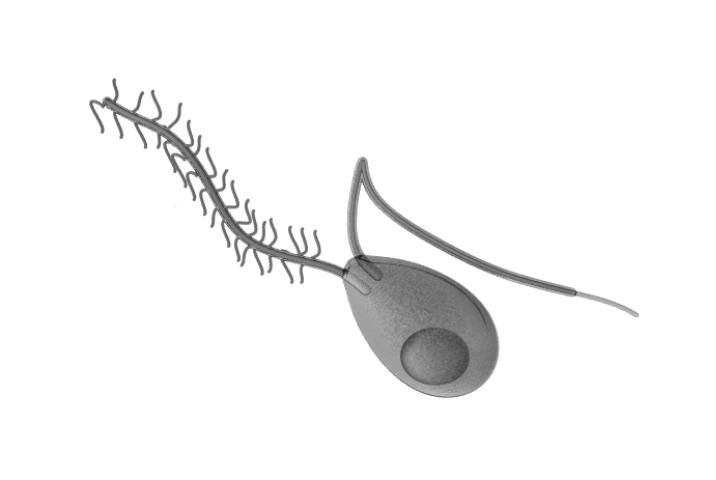

Upon landing on the leaf surface, each sporangia can release 5–15 zoospores, the main spore type responsible for infecting the plant. Zoospores are biflagellate spores, containing an anterior and a posterior flagellum (Figure 6) that allows them to move in water on the leaf surface. Once a spore locates a stomate on the leaf, the spore will stop moving (encyst) and produce a germ tube. The ideal temperature for encystment is 25°C (77°F). This germ tube is responsible for penetrating the stomate and infecting the host cells.

Credit: Cronodon.com

After infection, mycelium will grow between and within the host cells. This mycelium acts as a network for absorbing and transporting nutrients and acts as an infrastructure for other structures later in the infection cycle. Under a microscope, the mycelia are transparent (hyaline) and lack cross-walls (aseptate). The mycelium will eventually develop a haustorium, an anchor-like structure, which facilitates absorption of nutrients from the host.

Credit: S. J. Medrano

What are primary and secondary inoculum?

Primary Inoculum: The first spores or infectious units, which cause infection. This is what begins the disease.

Secondary Inoculum: The next generation of the pathogen population. This is often produced in the field. This is what escalates the disease.

What is a zoospore?

A zoospore is a mobile spore with two tails (flagella).

What is mycelium?

Mycelium (pl: mycelia) is a vegetative tissue that absorbs nutrients and acts as an anchor for other structures.

What is encystment?

Encystment is when a spore is entering a phase of suspended animation. During this time, the spore is immobile and is no longer searching for a stomate.

What is a stomate?

A stomate (pl: stomata) is an opening in the leaf used for gas exchange. These are often common routes of entry for pathogens within a plant.

Host Range and Pathotypes

Cucurbit downy mildew can affect over 40 species of cucurbits. Host specialization has been observed. The pathogen can be broken down into five pathotypes based on their host range and compatibility. For example, pathotype 1 can infect cucumber and cantaloupe and is incompatible with a watermelon host. Below is a table from work published in 1987 designating pathotypes based on host compatibility (Thomas et al. 1987).

Management of Downy Mildew for the Three Production Regions of Florida

Managing cucurbit downy mildew requires an integrated approach and should include avoidance, monitoring, resistance, cultural practices, and the application of protective fungicides. For management, the state is divided into three regions. The north region includes the panhandle. The central region is defined as below the I-10 corridor and above the I-4 interstate. The south region is defined as below the I-4 interstate. Each management approach is recommended for the regions in parentheses.

Early Planting (North and Central Florida)

Early season plantings may be less impacted by downy mildew. Downy mildew prevalence increases during summer and fall production. By planting when the disease is less prevalent, growers can reduce disease pressure and reduce the need for fungicides. This is an important strategy for the northern and central regions. Given the constant presence and reintroduction of downy mildew in the southern region, this strategy is not effective for that region.

Monitoring (North and Central Florida)

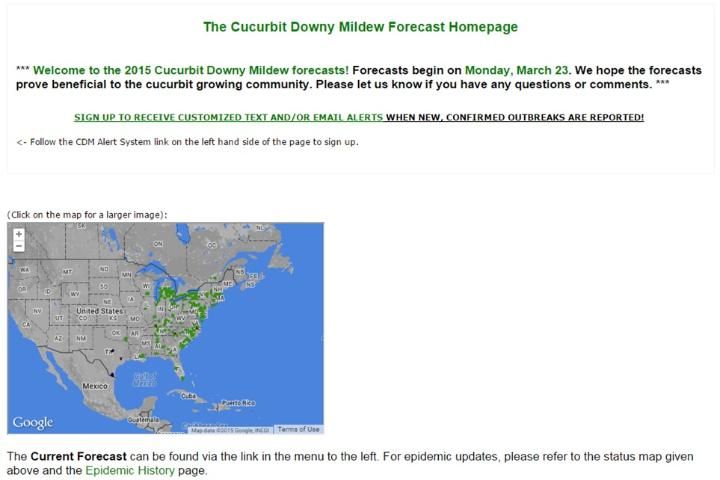

A nationwide monitoring system (IPM PIPE) has been developed at North Carolina State University and should be used closely while planting susceptible hosts in your region. The forecast homepage can be found at http://cdm.ipmpipe.org/ (Figure 8).

Credit: http://cdm.ipmpipe.org/

The IPM PIPE should be used in addition to field scouting, which should be done frequently and regularly to detect the disease as early as possible. Both of these practices will help you decide when to start applying fungicides. Good control is achieved by early detection and timely fungicide application. Note that the forecasting only tracks disease development from the airborne movement of spores. Other means of transmission, such as infected transplants, may not be detected.

Growers should also monitor weather conditions and apply protective sprays when conditions are conducive to disease development, particularly when plants have grown sufficiently and begin touch each other or cover the top of the beds. Once the disease is reported in your county or is scouted in your own field, the addition of a "systemic" or penetrant fungicide (such as Quadris®, Ridomil®, or Previcur Flex®) is recommended. Follow the label for appropriate rates and resistance management guidelines.

Resistant Varieties (North, Central, and South Florida)

The use of resistant varieties is a very efficient management strategy. A list of tolerant and resistant varieties has been provided. When possible, a resistant variety should be chosen, especially if downy mildew historically has been reported during the growing season. This is recommended for all three regions in Florida.

Tolerant and Resistant Varieties

Cucumber (Slicing)

- 'SV3462CS'***

- 'SV4719CS'***

- 'Cortez'

- 'Darlington'

- 'Dasher II'

- 'Daytona'

- 'Diomede'

- 'Dominator'

- 'General Lee F1'

- 'Green Slam F1'

- 'Indy F1'

- 'Intimidator F1'

- 'Lider'

- 'Lisboa'

- 'Marketmore 76'

- 'Marketmore 97'

- 'Olympian F1'

- 'Poinsett'

- 'Rockingham'

- 'Senor'

- 'Shantung Suhyo Cross F1'*

- 'Slice more'

- 'Soarer F1'*

- 'Speedway F1'

- 'Stonewall'

- 'Summer Top F1'*

- 'Talladega'

- 'Tasty Green'*

- 'Thunder F1'

- 'Turbo'

- * Specialty Asian type

- *** Improved Downy Mildew Resistance

Cucumber (Pickling)

- 'Calypso'

- 'Cross Country F1'

- 'Diamant'

- 'Eclipse'

- 'Eureka F1'

- 'Excursion'

- 'Expedition'

- 'Fancipak M'

- 'Jackson'

- 'Lafayette'

- 'Little Leaf H-19'

- 'Max Pack'

- 'Sassy F1'

- 'Supremo'

- 'Vlasstar'

- 'Wautoma'

- 'Zapata'

Muskmelon

- 'Ambrosia F1'

- 'Hannah's Choice F1'

- 'Primo'*

- 'Sun Jewel'**

- *Western Type

- **Asian Type

Melon (specialty)

- 'Crème de Menthe'*

- 'Crete'*

- *Honeydew melon

Note: This is not a complete list as new varieties are constantly being developed and many names can change. Consult your local Extension office or seed supplier for more information.

Chemical Control (North, Central, and South Florida)

Protective fungicides should be considered for use once downy mildew is reported in the area. Common recommended protective products include chlorothalonil, mancozeb, and copper. These products are designed to prevent infection from occurring, but have limited control once the disease is established inside the plant. Once downy mildew has been discovered in your field, it is necessary to add penetrant/"systemic" fungicides to your disease management program in order to achieve the best possible control. A spray program applied weekly or biweekly, depending on disease pressure, is recommended. Begin preventative sprays at transplanting or seedling emergence. To improve downy mildew control, a "systemic" product should be added once the disease is reported in your county or is observed in your field.

The Vegetable Production Handbook of Florida has a list of labeled products for control of cucurbit downy mildew (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/cv/cv12300.pdf). This list is continually changing based on product labels and new product releases. Always consult with your local UF/IFAS Extension agent, consultant, or agricultural chemical representative for more information on products available in your area.

Organic Production

The most important downy mildew disease management strategy for organic production is to use resistant varieties (see previous list). Other management strategies include early plantings, limiting optimal environments, and the use of biopesticides. In general, the efficacy of biopesticides is limited to use as a preventative product, which means disease monitoring is critical to the success of these products. Organic producers are highly encouraged to scout their fields regularly for the disease and to use disease monitoring tools (e.g., IPM PIPE). Producers with a high risk for downy mildew are encouraged to use an OMRI-listed fixed copper product to prevent infection. Other products are available, but their efficacy is often variable.

Selected References

Colucci, S. J., and G. J. Holmes. 2010. "Downy Mildew of Cucurbits." The Plant Health Instructor. DOI: 10.1094/PHI-I-2010-0825-01 http://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/intropp/lessons/fungi/Oomycetes/Pages/Cucurbits.aspx

Keinath, A. 2015. "Cucurbit Downy Mildew Management for 2015". http://www.clemson.edu/psapublishing/PAGES/PLNTPATH/IL90.pdf

McGrath, M. T., B. Gugino, K. Everts, S. Rideout, N. Kleczewski, and A. Wyenandt. 2013. "Effectively Managing Cucurbit Downy Mildew in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic Regions of the US in 2013" Penn State Extension. http://extension.psu.edu/plants/vegetable-fruit/news/2013/effectively-managing-cucurbit-downy-mildew-in-the-mid-atlantic-and-northeast-regions-in-2013

Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI). http://www.Omri.org (add when accessed)

Sitterly, W. R. "Downy Mildew". Compendium of Cucurbit Diseases. APS Press. St. Paul, MN 1996

Thomas, C. E., T. Inaba, and Y. Cohen. 1987. "Physiological Specialization is Pseudoperonospora cubensis" Phytopathology 77:1621–1624.

Vegetable MD Online "Cucumber/Pickles Disease Resistance." 2016. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Department of Plant Pathology. Retrieved July 30, 2015. http://vegetablemdonline.ppath.cornell.edu/Tables/Cucurbit_cucumber%20pickles%20table2016.pdf

Vegetable MD Online "Cucumber Slicers: Disease Resistance Table." 2016. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Department of Plant Pathology. Retrieved July 30, 2015. http://vegetablemdonline.ppath.cornell.edu/Tables/Cucurbit-cucumber%20slicers%20table2016.pdf

Vegetable MD Online. "Muskmelon: Disease Resistance Table." 2016. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Department of Plant Pathology Retrieved July 30, 2015. http://vegetablemdonline.ppath.cornell.edu/Tables/Cucurbit_muskmelon%20table2016.pdf

Vegetable MD Online. "Watermelon:Disease Resistance Table." 2016. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Department of Plant Pathology. Retrieved July 30, 2015. http://vegetablemdonline.ppath.cornell.edu/Tables/Cucurbit_watermelons%20table2016.pdf

Vegetable MD Online. "Yellow Summer Squash: Disease Resistance Table." 2016. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Department of Plant Pathology. Retrieved July 30, 2015. http://vegetablemdonline.ppath.cornell.edu/Tables/Cucurbit_yellow%20squash%20table%202016.pdf