This publication is intended for Florida blueberry growers to use as a diagnostic field guide in the identification and management of common leaf diseases on southern highbush blueberry (SHB). Management recommendations include fungicide applications and horticultural inputs intended to reduce disease severity.

Introduction

Southern highbush blueberry (SHB) cultivars are commercially grown throughout much of Florida in both deciduous and evergreen production systems. Growers in deciduous production should strive to keep leaves healthy through flower bud differentiation in fall to ensure optimum yield potential. In evergreen production, it is critical to maintain the prior year’s foliage through the winter months to support early fruit production the following season. In both systems, leaves can be damaged by many factors, such as environmental conditions, chemical applications, insects, and diseases.

This publication includes basic information to assist growers in determining 1) the likely cause (fungal, viral, algal, or bacterial) of leaf symptoms; 2) when specific leaf spots are likely to occur; 3) characteristic symptoms of common leaf problems; and 4) some of the available management options. Not all diseases can be diagnosed definitively by symptoms because symptoms can vary over time and on different blueberry cultivars. Symptoms with different causes can have similar appearances, and more than one disease can occur on the same leaf. Growers should consult UF/IFAS Extension or use a lab diagnostic service. Blueberry disease samples can be sent to the UF/IFAS Plant Diagnostic Center or another diagnostic lab for accurate identification of the problem.

Several leaf diseases affect SHB in Florida and have the potential to defoliate bushes. For fungal leaf diseases, growers have many effective chemical management options; however, proper product selection and timing of application depend on correct disease diagnosis. Because fungicides are only effective for fungal diseases, differentiating between symptoms caused by fungi and other factors can help prevent unnecessary fungicide use and costs.

The first step in diagnosing the cause of leaf symptoms in blueberries is to determine if the cause is an abiotic factor (e.g., environmental conditions such as freeze or drought stress, nutrient deficiency or toxicity, herbicide damage, mechanical damage, etc.) or a biotic factor (e.g., plant pathogens). Abiotic and biotic factors are not mutually exclusive; in fact, some abiotic factors can increase biotic susceptibility. The UF/IFAS Blueberry Growers Guide scouting app contains images of many different leaf symptoms caused by a variety of abiotic problems as well as diseases. See the following sections for specific information about differentiating and managing blueberry leaf diseases.

General Key for Leaf Symptoms

A. Round or irregular spots (lesions), usually surrounded by a dark border or yellow halo. Spots may be cultivar-specific and will usually increase in number over time in a nonuniform, random pattern before causing leaves to fall from the bush. In some cases, tiny black pimple-like reproductive structures and/or pustules (masses of spores) can be seen with a hand lens: Fungal disease (1).

B. Pale yellow to white discoloration of leaves, usually accompanied by red blotches on the stems or canes: Algal disease (2).

C. Red, purple, or black rings of discoloration on leaves. Centers of rings usually remain green. Rings may grow together or form concentric patterns of discoloration. They are usually most visible on older leaves, which may fall prematurely. No spores or reproductive structures are observed: Viral disease (3).

D. Plants look wilted, and some or all canes have a marginal leaf burn. The burn on the leaf edge progresses inward, sometimes leaving a green oak-leaf pattern in the center. Dead leaves do not fall from the bush. No spores or reproductive structures are observed: Bacterial disease or abiotic stress (4).

1. Fungal Diseases

1.1 Irregular lesions with a red-to-brown center and a darker border, ranging in size from 1/4 inch (around 6 mm) to 1 inch or more (25 mm), and often associated with a bud or twig blight. Leaf symptoms can occur any time of the year, with twig and bud blight being more common in winter through harvest. Lesions may look similar to Phyllosticta: Phomopsis.

1.2 Uniform, small, nearly round lesions with light gray centers and a dark purple border that are less than 1/4 inch (up to 6 mm). Most common from harvest until late spring and again in late fall to early winter: Septoria.

1.3 Bright yellow-orange pustules of spores visible on the underside of leaves, small (roughly 1/4 to 3/8 inch [6–10 mm]), somewhat angular dark brown lesions surrounded by red or yellow on upper leaf surfaces. Most common from late harvest through early summer and again in fall through winter: Rust.

1.4 Large circular or irregular lesions that are 1/4 to 3/4 inch (6–20 mm) across and dark brown with a yellow halo. Concentric patterns where shades of lighter and darker brown sometimes resemble a bull’s-eye. Lesions usually appear on the leaf edge from early summer through fall: Anthracnose.

1.5 Reddish to brown lesions of 3/8 inch (10 mm) or less, with an angular or irregular shape and a dark brown border. Concentric patterns of light gray to dark brown, sometimes with a bull’s-eye pattern. Most common in mid to late summer: Target spot.

1.6 Chestnut brown lesions, similar in size to anthracnose (roughly 1/8 to 3/4 inch [10–20 mm]), with a darker thin border and distinct tiny black pimples throughout. Most common in late summer through fall. Lesions may look similar to Phomopsis: Phyllosticta.

1.7 Angular lesions on upper leaf surfaces with colors ranging from dark reddish brown to dark purple necrotic, thin or no borders, and a general yellowing of severely affected leaves. Sporulation of the fungal pathogen is typically visible on the underside of affected leaves collected directly from the field. The sporulation looks like a dingy gray to black stain in the same angular shape as the upper leaf surface discoloration. Common from spring through harvest but may occur year-round: Cercospora.

1.8 Dense patches of powdery white growth that are present on the leaf surface and can be rubbed off easily. Usually accompanied by red discoloration. Almost exclusively a problem in high-tunnel production or greenhouse-grown plants: Powdery mildew.

2. Algal Disease

2.1 Early symptoms include small red blotches or lesions on green juvenile stems. These lesions expand to form irregular cankers that can encircle canes. Leaves on symptomatic canes bleach white to pale yellow, and growth of the entire plant can be severely stunted as the disease advances. Although not common, leaf infections can also occur with bright orange spots of algal growth: Algal stem blotch.

3. Viral Diseases

3.1 Red rings present on upper leaf surfaces only and primarily on older leaves. Rings also observable on stems, visible year-round, and persistent year to year: Blueberry Red Ringspot Virus.

3.2 Dark purple to black rings of dead tissue with green centers that occur on both sides of a leaf. Many rings can grow together into unusual shapes and patterns. Most common in late summer and do not persist year to year: Blueberry Necrotic Ring Blotch Virus.

3.3 Highly irregularly shaped red concentric rings on the upper and lower surfaces of leaves. There are no rings on stems. They do not persist year to year: Red variant of Blueberry Necrotic Ring Blotch.

4. Bacterial Diseases

4.1 Marginal-irregular leaf scorch may appear, similar to bacterial wilt or drought stress. Initial symptoms are observed on leaves attached to individual stems or groups of stems on one side of a plant. Plant vigor is reduced; stems and twigs of some cultivars acquire a distinctive yellow color, and the bushes eventually die: Bacterial leaf scorch.

4.2 Marginal leaf burn and wilting. The crowns of infected blueberry plants have an internal mottled discoloration of light brown to silvery-purple blotches with ill-defined borders. Wood chips from the crowns of plants that have bacterial wilt will stream bacterial ooze when floated in water: Bacterial wilt.

Fungal Leaf Diseases

Phomopsis Twig Blight and Leaf Spot

The pathogen Phomopsis vaccinii causes canker, twig blight, and fruit rot diseases. Occasionally, it is also associated with leaf spots. However, it is currently of minor importance on SHB in Florida. Phomopsis is characterized by irregular lesions on the leaf surfaces or edges. The lesions have a red-brown center surrounded by a darker border (Figure 1) and are very similar to those caused by Phyllosticta leaf spot. Phomopsis also produces reproductive structures (pycnidia) similar to but slightly larger than those produced in Phyllosticta lesions.

Credit: N. Flor, formerly UF/IFAS

Septoria

Septoria leaf spot is a common and prevalent disease in the southeastern United States caused by Septoria albopunctata. Severe infections can decrease yield due to reduced levels of photosynthesis, premature defoliation, and reduced flower bud production. Septoria spots are numerous but small (about 1/8 inch) and nearly circular. Spots have light brown to gray centers with broad purplish margins (Figure 2). The lesions can grow together into larger necrotic areas prior to defoliation. Symptoms tend to be more severe on older leaves, which are close to the ground. Reproductive structures (pycnidia) of the fungus are very small and are rarely found in the lesions. The disease typically occurs from mid to late harvest through June and may reappear during mild wet periods in the fall.

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Disease Cycle

S. albopunctata can overwinter in infected or dead leaves and stems or on other plant hosts. Mild wet weather (75°F–82°F) promotes spore germination and infection. Initial lesions serve as an inoculum source for further disease development. Spores are spread by water splash (rain and overhead irrigation).

Management

Applications of protective and systemic fungicides with different modes of action help to reduce Septoria leaf spot severity. Fungicides of FRAC group 3, such as OrbitTM, IndarTM, QuashTM, Quilt XcelTM, and Proline, and fungicides of other FRAC groups, such as Luna Tranquility (FRAC 7 & 9), Quadris Flowable® (formerly Abound; FRAC 11), SwitchTM (FRAC 9 & 12), PristineTM (FRAC 11 & 7), and BravoTM (FRAC M5), are effective against this disease. Systemic phosphite fungicides such as Agri-FosTM, ProPhytTM, and similar phosphonate products are also effective against Septoria; however, they must be applied after harvest to avoid possible fruit damage.

Rust

In Florida, this disease is caused by Thekopsora minima (formerly Naohidemyces vaccinii or Pucciniastrum vaccinii). Infected bushes can show premature defoliation, decreased floral bud differentiation, and reduced yield. Different levels of susceptibility to this disease can be found in SHB; for example, certain cultivars, such as ‘Jewel’ and ‘Optimus’, are known to be highly susceptible.

In the deciduous production system, disease progress and spore numbers largely halt when plants drop their leaves in response to low temperatures or hydrogen cyanamide application (December). The population of the rust fungus diminishes during the defoliation period, and relatively lower levels of the pathogen are present in spring, when the disease cycle restarts on new leaves.

However, in evergreen production, infected leaves persist and the disease produces spores through the winter months and harvest season (March to May). Leaf rust can become quite severe during the mild winters of southern production areas through spring harvest.

Symptoms are initially observed on the upper leaf surface and begin as small, somewhat angular yellow spots that turn reddish brown to black over time. Symptoms tend to be limited by larger leaf veins, resulting in lesions with parallel straight or angular sides. Multiple black-to-red lesions can occur on the same leaf, ultimately turning the leaves yellow and red (Figure 3) before causing defoliation. Brightly colored yellow-to-orange spores are produced on the underside of the leaf, opposite the lesions on the upper leaf surface. Masses of these spores are key to distinguishing this disease from other leaf spots (Figure 4). This disease gets its name from the distinctive rust color of these spores.

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Disease Cycle

Rust spores are spread efficiently by wind. The pathogen must have a living host to survive. In central Florida, the fungus survives mild winters on evergreen plants of Vaccinium species, in the environment surrounding production fields, or in blueberry plants in protected culture (such as high-tunnel production). In evergreen production in central and south Florida, the pathogen is known to survive in infected leaves that remain attached to the plants throughout winter. Occasionally, symptoms are observed on fruit when high levels of leaf symptoms persist from the previous season, although fruit infection is not common. New leaf infections can begin in spring during or just after harvest, and disease activity increases again in early fall.

Management

Applications of fungicides are the best method of control. Systemic fungicides can move into the infected leaves and potentially stop rust development. However, most products will only reduce or delay the amount of sporulation because fungicides do not effectively kill the fungus inside the leaf. Fungicides do a better job protecting against new infections, so making repeated applications to maintain a protective residue on the leaves is key to preventing the disease.

In the evergreen system, chlorothalonil (sold as BravoTM and others) applications for rust management can begin late fall, before bloom. Chlorothalonil is a contact fungicide that cannot be used after bloom, and some growers have concerns about causing leaf burn in the heat of summer. Chlorothalonil has efficacy for several diseases, and applications made when disease pressure is generally low but expected to increase are beneficial. As the season progresses, growers should scout for rust disease by walking rows, turning over leaves with spots, and looking for the orange spore masses. As rust starts to increase on the interior lower canopy leaves, consider using ProlineTM (prothioconazole), which has stood out in some published research as an excellent choice among demethylation inhibitor (DMI) products for rust. Other products with reported excellent effectiveness include Quilt XcelTM (azoxystrobin and propiconazole) and PropulseTM (fluopyram and prothioconazole). Consider other DMIs with longer preharvest intervals (PHI) if rust increases before bloom (e.g., IndarTM, TiltTM). They will have some efficacy, and this will leave QuashTM and ProlineTM (with a seven-day PHI) as options for any flare-ups closer to harvest. Quadris Flowable® (formerly Abound) and PristineTM also have rust efficacy and make for good rotation partners with one of the DMI products. If applied at or after bloom, consider tank mixing a captan product with Quadris Flowable® (formerly Abound) or PristineTM because of the widespread anthracnose ripe rot resistance to these products. Employing one or more of these options in the late fall to pre-bloom period should do a good job of keeping rust severity low through harvest. Fungicides with different modes of action should be used in rotation or in a tank mix as part of an integrated postharvest foliage management strategy.

Anthracnose

Anthracnose can cause symptoms on leaves, stems, and berries. For additional information, see EDIS publication PP337, “Anthracnose on Southern Highbush Blueberry.”

Anthracnose leaf spot (also known as Gloeosporium leaf spot) is caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. This disease can cause premature defoliation, poor bud development, and subsequent loss of yield. Typical symptoms are circular to irregularly shaped lesions, expanding from 1/4 inch to greater than 3/4 inch in diameter. The centers of the lesions are necrotic and range from brown to dark brown, with distinct concentric circles occasionally visible (bull’s-eye patterns) (Figures 5 and 6). These symptoms occur frequently at the edges of the leaves. Following extended moist conditions, examining the leaf spots with a dissecting microscope or a good hand lens will sometimes reveal tiny blister-like acervuli (spore-producing structures) with orange-to-salmon spore masses (Figure 7). Note that these are much smaller than rust pustules and not as routinely observed. Anthracnose leaf disease is common after harvest in Florida and persists through the summer. Blueberry cultivars differ in their susceptibility; ‘Jewel’ is considered very susceptible.

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Credit: M. Velez-Climent, formerly UF/IFAS

Disease Cycle

The fungus overwinters in infected leaves and stems from the previous season. In spring, when the weather gets warmer and more humid, the fungus produces spores called conidia. Conidia are spread by splashing water (rain or overhead irrigation), workers, and equipment. Once conidia land on plant tissue, they germinate and initiate new infection cycles through summer and into fall.

Management

Many registered fungicides are labeled for anthracnose on blueberry in Florida. Applications work best before symptoms become severe. On susceptible cultivars, applications to manage foliage health through flower bud differentiation should begin after postharvest pruning, with reapplications according to label instructions through September. DMI fungicides (FRAC 3) such as IndarTM, OrbitTM, QuashTM, Quilt XcelTM, and ProlineTM are options to be used in rotation or in tank mixtures with compatible products from another group to help prevent fungicide resistance. Fungicides with different modes of action, such as Luna TranquilityTM (FRAC 7 & 9), Quadris Flowable® (formerly Abound; FRAC 11), PristineTM (FRAC 11 & 7), SwitchTM (FRAC 9 & 12), and captan (FRAC M4), are suitable for rotation with DMI fungicides. Single applications of BravoTM (FRAC M5) are also recommended after harvest. Anthracnose resistance to Quadris Flowable® (formerly Abound) and other FRAC group 11 fungicides has been confirmed in central Florida, so these should be used in a premix product with two active ingredients or tank-mixed with another fungicide like captan to ensure efficacy. Fungicides with mono- and dipotassium salts of phosphorous acid, including Agri-FosTM, K-PhiteTM, and ProPhytTM (potassium phosphite), have systemic action. These “phites” have shown some effectiveness against anthracnose.

Target Spot

Target spot is caused by Corynespora cassiicola. The fungus has a wide host range and was first reported in blueberry in the United States in 2014. Florida growers have observed severe defoliation on many SHB cultivars since then. Typical symptoms are 1/3-to-3/8-inch angular to irregular reddish-brown lesions. As the lesions expand, color can vary in concentric rings, resulting in a “target” or bull’s-eye pattern (Figures 8 and 9). Symptoms can be difficult to differentiate from early symptoms of anthracnose leaf spot, and both diseases can occur on susceptible varieties at the same time. However, target spot lesions tend to remain smaller, whereas anthracnose leaf spots can increase to larger than 1/2 inch in diameter. Fewer target spot lesions are required before leaves fall from the bush compared to anthracnose.

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Disease Cycle

Limited information exists on the epidemiology of this fungus in blueberry. In other crops, C. cassiicola overwinters in plant debris or alternative plant host species. Environmental conditions such as humid weather, temperatures between 79°F–84°F, and moderate rainfall favor profuse fungal sporulation and rapid disease development. In the field, spores can be spread by wind or water splash (rain or irrigation).

Management

Growers have reported difficulty managing target spot once symptoms become apparent and severe. Preventive fungicide applications where the disease is known to occur, or careful scouting for the first disease symptoms, are encouraged. Limiting periods of leaf wetness and high humidity within the blueberry canopy also may help reduce disease severity by avoiding overhead irrigation, maintenance pruning to open canopies, and managing weeds in beds and row middles to increase air flow. No fungicide resistance is known at this time, and most fungicides that are used to manage anthracnose and rust should be effective against target spot. SHB varieties vary in their susceptibility to target spot, and ongoing research will provide additional information. Growers should ensure good, even coverage with spray equipment to increase the efficacy of the fungicides applied.

Phyllosticta

Phyllosticta leaf spot is caused by Phyllosticta vaccinii. This disease is more common later in the summer (August–September) than anthracnose. Symptoms are mahogany brown leaf spots with irregular borders. Lesions range from small (less than 1/4 inch) to larger than 1 inch (6–25 mm) prior to causing defoliation. Typically, lesions are surrounded by a dark brown to purple margin. A distinguishing feature of this disease is the presence of tiny black fungal pimples (pycnidia, the reproductive structures) that develop within the lesions (Figure 10). However, other fungi, including some that do not cause disease, can also produce small black structures on dead or decaying leaves. This disease is common in Florida, but it is considered of minor importance.

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Disease Cycle

Limited information exists about the infection process and epidemiology of this disease in blueberry.

Management

There are no published fungicide recommendations for Phyllosticta leaf spot management on blueberry in Florida; however, in other crops (cranberry, maple), related diseases are managed with applications of the contact fungicide BravoTM (FRAC M5). General maintenance applications of contact fungicides like BravoTM or captan are recommended after harvest as needed or approximately every two weeks (for up to six weeks).

Cercospora (Gleocercospora)

Cercospora (Gleocercospora), a new disease on blueberries in Florida, was first observed in 2022 on ‘Sentinel’ and has been observed every year since, impacting many additional varieties across farms from north–central to south–central production. The disease is listed in the American Phytopathological Society’s Compendium of Blueberry Diseases, but no research has been conducted on it for the last 50 years or so. Quite a bit has changed since then in terms of names of fungi, and our initial investigation into the fungus suggests it is likely a Pseudocercospora sp.

The symptoms are distinct but vary slightly in the most susceptible varieties like ‘Sentinel’ compared with more resistant varieties and selections. The symptoms are visible on upper leaf surfaces and tend to be angular in shape with colors ranging from dark reddish brown (Figure 11) to dark brown necrotic and a general yellowing of severely affected leaves (Figure 12). Some defoliation has been observed, but leaves can remain on the bush despite a surprising amount of symptoms. Sporulation of the fungal pathogen is typically visible on the underside of affected leaves collected directly from the field or may be produced with incubation in a moist chamber. The sporulation looks like a dingy-gray to black stain in the same angular shape as the upper leaf surface discoloration (Figure 13). Some varieties show abundant sporulation on the lower leaf surface but little to no upper leaf symptoms. The fungus produces spores in open clusters that can be seen as tiny black dots within the gray discoloration on the underside of affected leaves. These clusters can be confused with symptoms caused by blueberry necrotic ring blotch virus, which lack the black-to-gray sporulation and tend to be more circular than angular.

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Management

Horticultural inputs that help promote healthy, vigorous plant growth are encouraged to reduce plant stress. Leaf wetness and humidity management in the canopy of plants can help reduce disease pressure of many fungal diseases. Specific recommendations include selective pruning and weed management to improve airflow and encourage the drying of leaves and stems after rain, irrigation, or dew events. Avoiding overhead irrigation applications that extend leaf wetness may also help reduce the severity of common foliar diseases. Related fungi cause cercospora leaf spots on a diverse range of ornamental and crop plants, and resistant varieties are used where available, like with sugar beet production. Fungicide resistance within Cercospora species has been well-documented for several modes of action on beets and other crops. However, fungicide resistance has not yet been confirmed for blueberry, and until then, it will need to be monitored.

There are no fungicide recommendations specifically for cercospora (gloeocercospora) leaf spot on blueberry, but knowing what is effective for related pathogens can help give a starting point. DMI fungicides are some of the most effective products used on related pathogens across multiple crop systems, with contact products that contain chlorothalonil and copper reported as less effective but consistent. We use several of these for rust prevention during the periods of the year when cercospora leaf spot tends to occur. Fungicides like azoxystrobin can work well for many related cercospora diseases of other crops, but resistance renders them ineffective where present. This blueberry disease has occurred on farms even while using a good rust fungicide program, so additional work is needed to know what additional inputs can be used to try to prevent severe disease. The economic importance of managing this disease is still unknown, and whether a return on fungicide investment in increased yields will be realized by attempting control is an equally important question.

Powdery Mildew

Powdery mildew, caused by Microsphaera vaccinii, is a common disease of blueberries in greenhouses, high tunnels, or other protected production systems throughout the United States; however, the disease is usually not severe enough to affect fruit production. Powdery mildew rarely causes symptoms on SHB in the field in Florida. Extended high humidity promotes the development of this disease, but rain and overhead irrigation do not. Symptoms of this disease include white dense powdery mycelia and microscopic chains of conidia covering the leaf surfaces (Figure 14). Other symptoms may include irregular red discoloration of leaves. These spots can be confused with symptoms that are caused by viruses, but have fungal structures, usually on the underside of affected leaves.

Credit: N. Flor, formerly UF/IFAS

Management

Chemical control is not usually necessary; however, for sanitation or under high disease pressure, demethylation inhibitor (FRAC 3) fungicides such as OrbitTM, QuashTM, and TiltTM are recommended. Fungicides with dual modes of action, such as PristineTM (FRAC 7 & 11) (succinate dehydrogenase and quinone outside inhibitors), are also effective.

General Fungal Leaf Disease Management

Horticultural inputs can help reduce the likelihood and severity of fungal leaf diseases. Leaf wetness and high humidity are favorable conditions for disease development. Drip irrigation can help reduce moisture in the canopy compared to overhead irrigation. When overhead must be used, timing applications to correspond with periods when dew is present reduces additional durations of leaf wetness. Maintenance pruning bushes to increase air flow can help dry canopies, as can a good weed management program for rows and row middles. Implementation of good sanitation practices is also recommended to help reduce disease pressure. Remove diseased plant debris from the field to help reduce the number of fungal spores available to cause disease.

When using fungicides, plan applications to minimize the selection for fungicide resistance. Strategies to do this include utilizing fungicides with different modes of action (FRAC groups) in tank mixes or rotations. Avoid the exclusive use of a single fungicide or active ingredient (Table 1), follow all fungicide label directions, including minimum recommended rates and total applications per season, and utilize an integrated disease management strategy.

Algal Leaf Diseases

Algal Stem Blotch

Algal stem blotch is a disease caused by the parasitic green alga Cephaleuros virescens Kunze. The alga is thought to enter the plant through natural wounds and openings, pruning cuts, or direct penetration of the cuticle. Early symptoms include small red blotches or lesions on green juvenile stems. Leaves on symptomatic canes bleach white to pale yellow (Figure 15), and growth of the entire plant can be severely reduced as the disease advances. Leaf yellowing tends to occur on a few canes of each plant and differs from symptoms of nutritional deficiency in being less uniform and blotchier. Although not common, leaf infections can also occur with bright-orange spots of algal growth (Figure 16). For additional information, see EDIS publication PP344, “Algal Stem Blotch in Southern Highbush Blueberry in Florida.”

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Viral Diseases

Blueberry Red Ringspot Virus

Blueberry red ringspot virus (BRRV) causes symptoms on leaves, stems, and (rarely) fruit of susceptible cultivars. BRRV leaf symptoms include numerous roughly circular red rings (1/4 inch in diameter) with healthy light green centers (Figure 17). The rings (lesions) are more prevalent on the upper surfaces of older leaves and are not usually observed on younger leaves or lower leaf surfaces. In the fall, older leaves may cup and turn red prior to defoliation. Green stems also develop red rings during summer months that are visible through winter (Figure 18). Although BRRV persists in the plant from year to year, it does not appear to severely affect yield. There is no known vector of this virus; it is thought to be spread by propagation from infected, asymptomatic mother plants.

Credit: D. Phillips, UF/IFAS

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

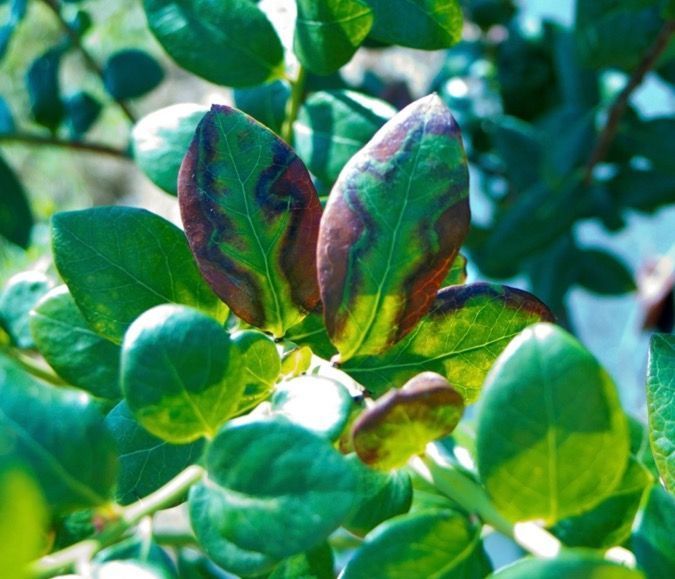

Blueberry Necrotic Ring Blotch Virus

Blueberry necrotic ring blotch virus (BNRBV) produces irregular rings of brown-to-purple discoloration visible on both upper and lower leaf surfaces (Figure 19). Similar to red ringspot virus, its rings have healthy green centers. These rings can expand and coalesce to form splotchy patterns on leaf surfaces prior to defoliation. A variant strain of the virus, where the lesions appear as red concentric irregular rings and unusual patterns, has been observed in Florida but is not common (Figure 20). BNRBV is believed to be vectored by a species of mite and does not persist in the plant from one year to the next. This disease is not thought to have a significant impact on yield, although in severe cases, summer defoliation can occur.

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Leaf Wilt and Scorch Symptoms

Leaves on plants that experience a lack of water for any number of reasons tend to show similar wilting symptoms followed by scorch (marginal burn) (Figures 21 and 22). A lack of soil moisture, salt stress (excessive fertilizer), and root-rotting or vascular-clogging diseases are common causes of wilt and scorch encountered in Florida SHB production. Abiotic factors such as drought, salt burn, or herbicide damage will generally affect weeds as well as blueberry in a uniform or predictable pattern associated with the application of fertilizer or herbicides. Check for potential abiotic causes of leaf scorch before considering potential disease issues. The following section includes examples of diseases that cause these types of symptoms.

Bacterial Diseases

Bacterial Leaf Scorch

Bacterial leaf scorch, caused by Xylella fastidiosa, was identified on blueberry in 2006 in the southeastern United States. Symptoms start as a marginal-irregular leaf scorch (Figure 21). Initial symptoms are observed on leaves attached to individual stems or groups of stems on one side of a plant. Plant vigor reduces, stems and twigs of some varieties, such as ‘Meadowlark’, acquire a distinctive yellow coloration (Figure 22), and the bushes eventually die. Diseased plants are typically observed randomly scattered throughout a field, rather than in distinct circles or groups within a row. Infected plants should be removed and destroyed. This bacterium is vectored by insects called sharpshooters and spittle bugs, including the glassy-winged sharpshooter (Homalodisca vitripennis). Controlling the vector with recommended insecticides may reduce infection levels.

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Bacterial Wilt

Plants with bacterial wilt show signs of drought stress, such as marginal leaf burn and wilting (Figure 23). Infected plants may also be prone to developing severe symptoms of other stress diseases, such as stem blight. The Ralstonia pathogen that causes bacterial wilt can be spread easily in water, soil, or infected plant material. For additional details on bacterial wilt, see EDIS publication PP332, “Bacterial Wilt of Southern Highbush Blueberry Caused by Ralstonia solanacearum.”

Credit: P. Harmon, UF/IFAS

Table 1. Calendar of blueberry leaf disease activity and potential fungicide management options. Legend: Orange shading represents the time span for bloom, harvest, and postharvest timing; blue shading represents the time span when disease is typically observed; and the gray shading represents the time span when disease is occasionally observed.

February through March for north-central, January through March for central and south-central in most years. Check the preharvest interval of all products.

April through May for north-central, March through May for central and south-central in most years. Check the preharvest interval for all products.

June through December for all regions in most years.

References

Brannen, P., and P. Smith, eds. 2018. Southeast Regional Blueberry Integrated Management Guide. University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://extension.uga.edu/content/dam/extension/programs-and-services/integrated-pest-management/documents/handbooks/2018%20BlueberrySprayGuide.pdf

Brent, K. J., and D. W. Hollomon. 2007. Fungicide Resistance in Crop Pathogens: How Can It Be Managed? 2nd revised edition. Fungicide Resistance Action Committee. https://www.frac.info/media/jtafagre/monograph-1.pdf

Fungicide Resistance Action Committee. 2019. FRAC Code List© 2019: Fungal Control Agents Sorted by Cross Resistance Pattern and Mode of Action (Including FRAC Code Numbering).

Harmon, P. F., C. Harmon, and D. Norman. 2016. “Bacterial Wilt of Southern Highbush Blueberry Caused by Ralstonia solanacearum: PP332, 11/2016.” EDIS 2016 (9). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-pp332-2016

Harmon, P. F., O. E. Liburd, P. Dittmar, J. Williamson, and D. Phillips. 2024. “2024 Florida Blueberry Integrated Pest Management Guide: HS380/HS1156, rev. 8/2024.” EDIS 2024 (4). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-hs380-2021

Hongn, S., A. Ramallo, O. Baino, and J. C. Ramallo. 2007. "First Report of Target Spot of Vaccinium corymbosum Caused by Corynespora cassiicola." Plant Disease 91 (6): 771. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-91-6-0771C

Norman, D. J., A. M. Bocsanczy, P. Harmon, C. L. Harmon, and A. Khan. 2018. "First Report of Bacterial Wilt Disease Caused by Ralstonia solanacearum on Blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum) in Florida." Plant Disease 102 (2): 438. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-06-17-0889-PDN

Onofre, R. B., J. C. Mertely, F. M. Aguiar, et al. 2016. "First Report of Target Spot Caused by Corynespora cassiicola on Blueberry in North America." Plant Disease 100 (2): 528. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-03-15-0316-PDN

Pernezny, K., M. Elliot, A. Palmateer, and N. Havranek. 2008. “Guidelines for Identification and Management of Plant Disease Problems: Part II. Diagnosing Plant Diseases Caused by Fungi, Bacteria and Viruses: PP249/MG, 2/2008.” EDIS 2008 (2). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-mg442-2008

Phillips, D. A., N. C. Flor, and P. F. Harmon. 2018. “Algal Stem Blotch in Southern Highbush Blueberry in Florida: PP344, 11/2018.” EDIS 2018 (6). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-pp344-2018

Phillips, D. A., M. C. Velez-Climent, P. F. Harmon, and P. R. Munoz. 2018. “Anthracnose on Southern Highbush Blueberry: PP337, 5/2018.” EDIS 2018 (3). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-pp337-2018

Polashock, J. J., F. L. Caruso, A. L. Averill, and A. C. Schilder, eds. 2017. Compendium of Blueberry, Cranberry and Lingonberry Diseases and Pests. 2nd edition. The American Phytopathological Society. https://doi.org/10.1094/9780890545386

Robinson, T. S., H. Scherm, P. M. Brannen, R. Allen, and C. M. Deom. 2016. "Blueberry necrotic ring blotch virus in Southern Highbush Blueberry: Insights into In Planta and In-Field Movement." Plant Disease 100 (8): 1575–1579. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-09-15-1035-RE

University of Wisconsin-Madison. 2005. “Early Rot in Wisconsin.” Special factsheet. https://fruit.webhosting.cals.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/36/2011/05/Early-Rot-Diseases-in-Wisconsin.pdf

Williford, L. A., A. T. Savelle, and H. Scherm. 2016. "Effects of Blueberry red ringspot virus on Yield and Fruit Maturation in Southern Highbush Blueberry." Plant Disease 100 (1): 171–174. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-04-15-0381-RE