Table of Contents

Introduction: What is 4-H?

The Case for 4-H Afterschool

What Is 4-H Afterschool?

How to Use This Resource Guide

Other Resource Guides in the 4-H Afterschool Series

Chapter 1: Get Ready

Assess Readiness of Citizens, CES

Deciding the Appropriate Role for County Extension Engagement in After-School Programs

Community-Managed Model for After-School Programs

Assess Yourself

Chapter 2: Conduct a Needs Assessment

Analyze Your Results

Chapter 3: Decide Next Steps

Establish Governing Structures

Space Considerations

Program Development

Mission, Vision, and Philosophy

Goals, Objectives, and Program and Evaluation Design

After-School Programs and Youth Development Models

Chapter 4: Develop a Budget

Start-Up Versus Operational Budgets

Income Sources and Considerations

Chapter 5: Write Policies and Procedures

Chapter 6: Put a Staff in Place

Develop a Staff Manual

Chapter 7: Keep Detailed Records

Chapter 8: Create a Parent Handbook

Chapter 9: Get the Word Out

Chapter 10: Evaluate Your Program

Plan Your Evaluation

Analyze the Data

Communicate the Results

Continue Improvement

Suggested Evaluation Resources

Chapter 11: Sustain Your Program

Collaborate, Collaborate, Collaborate

Conclusion

Appendix

Benefits of After-School Programs

Evidence-Based Practices for After-School Programs

Endnotes

Resources

Introduction: What is 4-H?

4-H is the Cooperative Extension System’s dynamic, non-formal, educational program for youth. It is known nationwide for engaging youth as leaders and giving them the power to take action. Through the Cooperative Extension System of land-grant universities, 4-H mobilizes trained, experienced, and competent educators in more than 3,000 counties across the United States, including the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa, Micronesia, and the Northern Mariana Islands, to support the community of young people who are learning leadership, citizenship, and life skills.

The 4-H mission is to help youth reach their full potential, working and learning in partnership with caring adults. The cooperation of nearly 6 million youth and 500,000 volunteer leaders, along with more than 3,500 professional staff, 112 state land-grant universities, state and local governments, private-sector partners, state and local 4-H foundations, National 4-H Council, and National 4-H Headquarters at the USDA makes 4-H happen.

This resource guide is designed to be used by Extension professionals in evaluating the need for and planning the establishment of new after-school options in communities with insufficient programs available for school-age youth. It represents some of the curricula, ideas, and information available throughout the Cooperative Extension System, governmental agencies, current research, and organizations involved in the after-school arena.

The Case for 4-H Afterschool

The evidence from research studies, national surveys, and public opinion polls shows the extensive benefits and support for after-school programs. Adults nationwide agree that high-quality programming is beneficial because young people spend the majority of their waking hours out of school.

In a national, random survey of parents of school-aged children, America After 3PM: Demand Grows, Opportunity Shrinks (2020), reported that:

- Eighty-four percent of parents agree that all young people deserve opportunities to participate in quality after-school and summer programs.

- Eighty-five percent of parents, regardless of political affiliation or geographical location, support public funding for after-school programs.

- Eighty-one percent of parents agree that after-school programs help working parents keep their jobs.

- Over 70 percent of parents agree that after-school programs provide a multitude of benefits for youth including learning life skills, fostering interest in learning, promoting healthy social activities and relationships, keeping kids safe and out of trouble, reducing the likelihood of risky behaviors, and more.

Also noted is that for every child participating in an after-school program, three more are unable to do so, thus causing an unmet demand of 24.6 million children nationwide (Afterschool Alliance, 2020). With a demand to serve 32.4 million youth, it is vitally important for public and private agencies and organizations to focus attention and resources on increasing the quality and quantity of after-school programs.

Similar results are noted by Afterschool Alliance (2022) in a poll of registered voters nationwide:

- Seventy-nine percent believed that after-school programs are an absolute necessity for their community.

- Eighty-three percent say that children in after-school programs are safer and less likely to be involved with risky behaviors.

- Eighty-four percent or more agree that after-school programs support youth development academically, socially, and emotionally, as well as build life skills such as teamwork and communication.

- Eighty percent wanted increased public funding for after-school programs.

Beyond the perceptions and public opinion, research studies have shown the effects of after-school programs on positive youth development. High-quality programs support cognitive, social-emotional, and behavioral development, as well as physical health (Sparr et al., 2021; Traphagen, 2014). Youth who attend these programs have demonstrated improved academic achievement, such as better school attendance and better grades. They also showed improved social skills, such as positive relationships with adults, opportunities to make new friends, greater self-concept, and higher self-esteem (Lee, 2012).

However, clear challenges exist in developing and implementing quality after-school programs. There are competing demands and expectations for out-of-school-time programs to provide academic support, STEM, creative arts, and physical and health education (Traphagen, 2014). Other challenges in this field involve developing and supporting a skilled and professional workforce, creating opportunities for all participants, disseminating research and assessments as tools for improvement, as well as augmenting systemic support (Reisner et al., 2007; Traphagen, 2014). Thus, to achieve the intended positive outcomes, it is important to intentionally design programs with a clear focus, skilled staff, sufficient time to accomplish goals, and adequate support. (See Appendix, pages 39–42, for a full discussion.)

The Cooperative Extension System’s (CES) mission is to help people put their knowledge to work, meet their needs, and solve their own problems. Today, after-school programs significantly impact issues of employment, education, environment, and economics. CES — with a presence in every county in the United States and trained staff in a broad range of academic disciplines — is uniquely suited to provide leadership for the after-school needs of families and communities. 4-H is well positioned for attracting new partners and financial resources through leadership in the after-school field because of its extensive county-based delivery system, highly trained youth development professionals, relationships with land-grant universities, and broad library of experiential learning curricula. After-school programs provide critical youth development opportunities in the 21st century, and CES has an important role to play.

Through developing, strengthening, and maintaining the quality and quantity of after-school programs, Extension can make significant contributions to this important national issue. Due to the frequency of youth engagement and opportunities for intense, sequentially planned learning experiences, after-school programs provide a delivery system in which 4-H youth development programs can have a strong impact. This guide focuses on addressing the quantity issues by helping to establish new community-managed programs (e.g., a community organization takes the responsibility for managing and operating the after-school program).

The information in this guide can assist Extension professionals in creating new programs to serve the needs of youth and families.

What is 4-H Afterschool?

4-H Afterschool programs combine the resources of 4-H and the Cooperative Extension System with programs that address community needs. The 4-H Afterschool program helps increase the quality and availability of after-school programs by:

- coordinating the development of new after-school programs,

- improving the ability of after-school program staff and volunteers* (youth and adults) to offer high-quality care, education, and developmental experiences for youth,

- increasing the use of 4-H curricula, which are peer-reviewed and research-based, in after-school programs,

- organizing 4-H clubs, which provide positive youth development programs, in after-school programs, and

- developing SPIN (special interest, short-term) clubs that focus on participants’ interests.

4-H Afterschool offers support and training materials, including this resource guide, to help leaders teach quality program activities. 4-H Afterschool trains staff and volunteers, develops quality programs, and creates communities of young people across America who are learning leadership, citizenship, and life skills.

The benefits of 4-H partnerships with after-school programs are numerous. County 4-H programs benefit by working with new partners and reaching new audiences. After-school programs benefit from the support and quality programming available through Extension. Above all, the children in the programs benefit through their experience.

* Any person who works with the 4-H club and is not paid by Cooperative Extension System funds is considered a volunteer. Thus, paid staff from other organizations are considered volunteers. Please refer to your respective state office for specific criteria to become a 4-H volunteer.

4-H Afterschool programs:

- are offered during the times children and youth are not in school (also called out-of-school time), including after-school hours, teacher workdays, school holidays, summer months, and weekends;

- provide safe, healthy, caring, and enriching environments for children;

- reach children and youth from kindergarten to twelfth grades;

- engage children and youth in long-term, structured, and sequentially planned learning experiences in partnerships with adults; and

- address the interests of children and youth, while helping to develop their physical, cognitive, social, and emotional skills and abilities.

How to Use This Resource Guide

This guide will assist Extension professionals in evaluating the need for and planning the establishment of new after-school options in communities with insufficient programs available for school-age youth. The chapters cover a range of steps and considerations, including conducting needs assessments, hiring and training staff, and program sustainability. However, this guide cannot cover everything required. Several resources that provide more in-depth information and tools are listed below, and numerous others are given in each chapter.

- Afterschool Alliance, www.afterschoolalliance.org

- Children, Youth, and Families at Risk, University of Minnesota, www.cyfar.org

- Expanded Learning, expandinglearning.org

- National Institute on Out-of-School Time, www.nios.org

- 4-H, https://4-h.org/programs/

- Youth.gov, https://youth.gov/youth-topics/afterschool-programs

- The Wallace Foundation, wallacefoundation.org

Other Resource Guides in the 4-H Afterschool Series

- Starting 4-H Clubs in After-School Programs helps afterschool sites start 4-H clubs.

- 4-H Youth Development Programming in Hard-to-Reach Communities aims to reach out to, increase programming for, and meet the needs of the full scope of audiences participating in 4-H after-school activities.

- Teens as Volunteer Leaders offers strategies on recruiting and training teens to work with younger youth in after-school programs.

Each of these guides is designed to be used independently. Nevertheless, the guides also work well together during the orientation and training of after-school staff and volunteers.

4-H’S Mission in the After-School Field

The mission of 4-H’s work in the after-school arena is to improve the quality and availability of after-school programs by linking the teaching, research, outreach education, technology, and 4-H youth development resources of the National 4-H Council, USDA, land-grant universities, and county Cooperative Extension offices to local communities across America.

Chapter 1: Get Ready

Assess Readiness of Citizens, CES

Understanding the capacities of the Cooperative Extension System is an important step when thinking of starting an after-school program. What are the interests, priorities, and capacity of the county and state? What are the skills and interests of the county Extension professionals in delivering the 4-H Youth Development Program in after-school settings? The assessment tool on page 12 can help focus some of these preliminary questions.

If the state or county is new to the after-school program arena, Extension professionals may need to build the case for the importance of Extension’s work in after-school programs with current stakeholders. This guide provides ample information to develop a strong rationale for the importance of Extension’s work in this area.

Deciding the Appropriate Role for County Extension Engagement in After-School Programs

In addition to considering the community needs and community organizations' involvement, Extension professionals must factor in their own organization’s level of participation. Work with your county Extension director, county advisory committee, 4-H advisory committee, and other key members to determine their level of support. An analysis of Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) can help identify your organization’s current abilities. This tool can aid with strategic planning in educational settings. See Conducting a SWOT Analysis for Program Improvement at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED543801.pdf (Orr, 2013) or Rutgers University website SWOT tool at https://libguides.rutgers.edu/SWOT.

The next step is to determine your organization’s parameters for involvement. These include time commitment, terms and focus of the partnership, and benefit to your organization. Consider how much time you can commit to training staff, as well as maintaining and sustaining a program, with this partnership. Lesser time commitments may have practical benefits yet may offer less sustainability and less impact, so the tradeoff of time investment versus program impact is an important consideration. Likewise, consider the terms and focus of the partnership. How long will this partnership last? Will you be required to remain actively involved after the training period? Will services be offered exclusively to youth, or will there be family involvement? Finally, focus on how this benefits your organization. What do you need from the partners (i.e., location, access to youth, financial assistance, staff involvement, etc.) to successfully implement the program (Spero, 2019a)?

Community-Managed Model for After-School Programs*

The next step is to determine whether the community stakeholders support delivering 4-H through the after-school market. (The assessment tool on page 12 will again help focus these questions, and the needs assessment in Chapter 2 will further this research.) If support needs are sufficiently met, this guide will help you in establishing community-managed after-school programs.

The community-managed model organizes concerned individuals, to address the need for after-school programs in the community, and an Extension professional, to act as the facilitator in many cases. The Extension professional guides the community through identifying problems and possible solutions, creating a plan of action, acquiring necessary resources, and implementing and evaluating programs. This role may involve bringing community leaders and concerned citizens together around the issue of after-school programs, perhaps to conduct the needs assessment process. Or, it may mean working with an existing group, such as the Parent Teacher Association/Organization (PTA/PTO), that has identified a need but is not sure how to proceed. The culmination of such a process may result in locating a community agency willing to undertake the responsibility of running the program or, if no such organizations are available, in creating a non-profit board with parent and community representatives to manage the program. As a result, quality after-school programs will be established or expanded to serve more children.

*Adapted from Dixon & Ferrari (2000); Ferrari et al. (2003); and Ferrari (1999).

The Extension professional may continue to work in a support role as the group is established or provide support in sustaining the program through areas such as grant proposal writing and evaluation. Those involved often find themselves in the role of informing public policy when they work with local school personnel on issues such as building use and transportation.

Community-managed programs do not appear overnight. They are the result of the work of dedicated individuals who believe they can make a difference. Community ownership increases the likelihood of creating sustainability because those involved in such a process often feel tremendous commitment toward the program. Nevertheless, a community-managed program requires significant time and energy because the facilitator is guiding a community group’s work toward a long-term goal. A key role of the Extension professional is to raise awareness of the elements of program quality and to ensure that any program established is of high quality.

Assess Yourself

Are you ready for a community-managed program?

Table 1. Example chart for self-assessment on whether you are prepared to manage an after-school program.

Chapter 2: Conduct a Needs Assessment

Sizing up the current situation in a community is the first task of a needs assessment. You can do that by asking several community-level questions:

- Do these communities already have sufficient after-school programs?

- Do all children and youth have access to affordable, quality programs?

- Do programs exist in economically deprived communities and communities with hard-to-reach populations?

- Where can Extension have the greatest impact and serve the greatest need?

Sample tools for conducting a needs assessment can be found from Virginia Cooperative Extension at http://hdl.handle.net/10919/48297 and Afterschool Alliance in conjunction with Utah State University Extension 4-H at https://extension.usu.edu/utah4h/files/afterschool-program-guide.pdf.

Census data, schools, and other public data sources also can provide valuable information.

Questions posed to parents, children, and youth may include the following:

- If we offer after-school programs, would you enroll your children?

- How would you determine whether a program is appropriate for your child?

- What kinds of programs would children and youth prefer?

- When do these programs need to be offered?

A community may appear to need after-school programs, but keep in mind that parents may have other options for after-school hours such as relatives, friends, or older youth to take care of younger children. The needs assessment is the best way to prioritize the communities and locations for Extension’s work. Define the scope of the assessment by the amount of programming you intend. Time and funding considerations may require you to focus on individual communities in the county.

Positive response to a needs assessment should help ensure “buy-in” from parents, schools, community and business leaders, and financial and in-kind sources of support. Make sure to involve a broad array of community members, including those with decision-making roles, in the needs assessment by organizing an advisory committee or expanding an existing committee.

Your needs assessment should have community support and program participation, which are two keys to sustainability. Ensure greater accuracy by using a variety of sources of information.

Before you start your needs assessment, determine how it will be conducted because they can take many forms. The methods used to collect the information can be very simple and done on a very limited budget, or they can be more formalized and costly.

TIP: Extension staff should check university policies regarding the involvement of the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) prior to developing the needs assessment and throughout the process. Many universities require IRB approval prior to the administration of survey, research, and/or evaluation instruments to protect the rights of human subjects. The policies, procedures, and requirements of the IRB may impact your timelines, content, and survey methods.

Regardless of the method you use, the following questions will prompt the type of data you need to collect for the needs assessment:

- How many children/youth are in the community/county?

- How many programs currently provide services for youth during non-school time?

- Do parents perceive a need for the program?

- What ages are the children who need the program?

- What accommodations would be necessary to ensure all children have the ability to participate?

- If the program is established, will parents allow their children to attend?

- How much are parents willing to pay for the program? On the assessment, parents need to indicate the maximum amount they can afford.

- Can parents afford the cost?

- What other funding sources are available?

- When should the program be offered: before school, after school, on teacher workdays, over holidays, and/or during summer break?

- What times should the program be open?

- What is the most convenient location for the program?

- Will parents need to provide transportation?

- What type of activities do parents prefer in the program: homework assistance, recreation, enrichment activities, something else, or a combination of some or all examples?

- Are any parents willing to assist with developing and implementing the program?

The local resource and referral agency or department of social services may be able to provide data regarding the number of after-school programs in the county and specifics about the youth served by the program.

You also might want to consider the following to find answers:

- Conduct focus group meetings

- Attend PTA/PTO meetings

- Talk with school principals and teachers

- Talk with law enforcement officers

- Interview people who work with city and county agencies (department of health and human services, department of social services, etc.)

- Conduct surveys

When using a survey instrument, consider the following guidelines. Include a cover letter that clearly explains the purpose and use of the survey. Let respondents know that the information is confidential and will only be used by authorized individuals working on the project. Provide respondents with a timeline for when the survey will be completed and when a decision will be made about starting a program.

Make sure sufficient time is allocated for all steps to be completed. It may take several months to a year between the administration of the survey and the first day of the program. Do not create expectations among parents about starting a program without a clear idea of when or if the program will begin.

You might want to consider using an outside source, like faculty or students from a local university or community college, to conduct the survey. If you use an outside source, ask about the cost and work closely with them to ensure the survey includes the information needed to make a decision. Prior to administering the survey, conduct a small pilot test to determine if the questions are clear and understandable. This test will help identify problem questions and refine the survey. Finally, include details like who is sponsoring the survey and contact information in the survey’s cover letter.

If your survey is custom-designed, keep these suggestions in mind:

- Decide how the survey will be administered (i.e., through school, mail or email, telephone survey, booth at the shopping center, etc.).

- Keep the survey as short as possible.

- Only ask questions necessary to determine the need for the program.

- Keep the wording simple and sentences short.

- Allow respondents to add comments.

- Sensitive personal information, such as income, should be placed at the end of the survey.

- Reassure respondents that the information is confidential and explain how the information will be used.

- Determine how the information will be analyzed.

- Consider the cost for developing, administering, and analyzing the data and make sure you have funds available to complete the process.

Analyze Your Results

Once you have conducted your survey, results must be analyzed to determine whether a need exists based on pre-determined parameters. Quantitative and qualitative data can be analyzed through statistical procedures and content analysis (Ruffin, 2019). Is there a particular region, population, or program type that is lacking and warrants the establishment of a new program? Is there sufficient interest and support from parents and other stakeholders? Your results will guide you in determining what steps to take next, as discussed in the following chapter.

Chapter 3: Decide Next Steps

Once you have completed the needs assessment and analyzed your results, it is time to make a decision. If the results show that parents do not want a program or sufficient programs are available to address the need, then it is not necessary to pursue the development of a new program in that particular community. At this point, other options are to conduct a needs assessment in a different community or to consider working to strengthen existing after-school programs by incorporating 4-H activities. For example, programs may use 4-H curricula, resources, or enrichment activities; Extension personnel can provide training for program staff; or short- or long-term 4-H clubs may be formed (Spero, 2019b). The 4-H Afterschool resource guide, “Starting 4-H Clubs in After-School Programs,” provides most of the information needed to start 4-H clubs within current after-school programs. These approaches will increase the enrollment in 4-H and afford youth the benefits of 4-H membership in local, county, state, and national programs.

If the results indicate a need for establishing an after-school program, and the support base is adequate, then it is time to start the process of establishing the program and its administrative procedures and responsibilities. Work with an existing community group, form a new committee, and/or help strengthen an existing committee. Iowa Afterschool Alliance has developed a manual to guide community groups as they establish childcare programs. This manual, Impact After School: After-school Program Start-Up Guide, has great applicability for groups establishing after-school programs, provides supplemental information to support this guide, and is available at https://www.scafterschool.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Impact-Afterschool-Start-Up-Guide-2012.pdf. Likewise, Afterschool Alliance in conjunction with Utah State University Extension 4-H has a full start-up guide for establishing new after-school programs, with examples, templates, and additional resources at https://extension.usu.edu/utah4h/files/afterschool-program-guide.pdf.

Establish Governing Structures

Youth development professionals, businesspersons, and other professionals like lawyers, accountants, county and city officials, and school personnel are all important people to involve on the program’s governing board and related committees. Since an after-school program is a small business, be sure to involve people who can help address the business-related issues as well as program development concepts.

Although some people with specific expertise may not be able to serve on the governing board or committees, they may be able to offer limited service to the work. For example, a city inspector may be willing to assist with building requirements. A consultant may be able to advise on the state’s school-age childcare licensing laws. A lawyer may be willing to provide pro bono legal services to the group.

The following list offers suggestions for the types of people that might serve on the board and/or committees:

- Cooperative Extension staff and faculty

- School personnel (superintendent, principals, teachers, school board members)

- PTA/PTO members

- Parents

- Business leaders

- Department of health and human services staff

- Department of social services staff

- Childcare resource and referral agencies

- Public and private childcare providers

- Licensing groups such as fire, health, building, and so forth

- Other youth service organizations (YMCA of the USA, Boys & Girls Clubs of America, etc.)

- Department of parks and recreation staff

- State, city, and county government representatives

- Civic group members

- Representatives from foundations and other potential funding partners

Questions for Governing Board

Some of the first questions the governing board will need to consider include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Legal

- What is the appropriate legal structure to protect all parties and the best structure for taxes and other considerations?

- What are the licensing and other requirements for operating a youth program in your state?

- Who needs to be involved (e.g., lawyers, accountants, investment counselors)?

- Will the group organize as a 501(c) (3) organization?

- Governance

- What is the size, function, role, and responsibility of the governing board?

- Will there be auxiliary committees to determine such things as curriculum, schedules, and so forth?

- What role will parents play?

- Program Administration

- Who will manage the day-to-day operations of the program?

- When will the program begin?

- How much will the program cost?

- What are the funding sources for the program? Parent feesGrant fundsSchool fundsDonationsIn-kind supportA blending of sourcesOther

- How many youth will be enrolled in the program?

- Will there be a sliding fee scale for families with more than one child and/or those with limited resources?

- What ages will the program serve?

- What is the operational schedule of the program?

- Will meetings occur on weekdays before and after school?

- What are the hours of operation? Will the program be available on weekends, holidays, teacher workdays, or summer break?

- What is the enrollment policy? Must children and youth be enrolled for an entire session, or is “dropping-in” allowed?

- Will nutritious meals and snacks be provided? Will existing staff or contractors prepare them?

- Will transportation be provided?

- Will field trips be a part of the program?

- What other facilities will be used? (e.g., local parks and recreation swimming pool, recreation facilities, a tour of a farm, etc.)

- How many staff will be hired?

- What qualifications will staff need?

- Will background checks be made? If so, how will they be conducted?

- Will college students and teens be allowed to work or volunteer in the program?

- How much will staff be paid?

- Where will the program be located? SchoolCommunity buildingChurch, synagogue, mosque, and so forthBoys & Girls Clubs of AmericaYMCA of the USAParks and recreation buildingCooperative Extension office

Space Considerations

The location of the program and the space made available to it are very important. Here are a few other considerations:

- Make sure the space is safe, clean, and in good condition. Check with the building inspector or fire marshal to determine if a license is required to open the program. If licensing is required, you will need the specifications for the building.

- The best situation is having a designated space for the program. If you must use shared space, try to ensure consistency and minimize disruption for the program staff. Staff and youth need a space they can consider their own. If the program is in a shared facility, try to get access to other areas such as the library, cafeteria, and gym.

- Does the facility have sufficient indoor and outdoor space?

- Does the facility have drinking water, restrooms, heating and cooling, a place to serve meals and snacks, a telephone that is always available, and a place where youth and staff can put their personal belongings?

- Is there water for cleaning, cooking, preparing snacks, and completing activities and projects?

- Is the furniture and play equipment, inside and outside, safe and age-appropriate?

- Is there storage space for supplies and materials?

- Is there sufficient space for a variety of activities such as active play space, a quiet space for resting, a place to read and do homework, a place to socialize with friends, and a place to play indoor games and board games? You should try to have five activity areas in a program. Do you have sufficient space for activity areas?

- Does the facility meet the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) requirements? (Visit www.ada.gov for requirements.)

This list is just the beginning. Talk with committee members and explore other questions that need to be answered before starting the program.

Program Development

Program development has several elements that include, but are not limited to, developing a vision, mission and philosophy statements, goals and objectives, and program design and curriculum. The quality of the program is extremely important, and Extension staff can play a vital role in ensuring program components are based on positive youth development principles, are of high quality, address appropriate content, and offer a broad variety of educational experiences. Process, outcome, and impact evaluations, discussed in Chapter 10, are important to put in place in this early developmental stage. A plan for sustaining the program is another important component of program development. It is extremely important to develop and articulate measurable goals, establish program strategies to achieve those goals, see outcomes, and design a methodology to evaluate them.

Mission, Vision, and Philosophy

As you develop the program, you will need to write a mission statement and develop your vision. These will drive program design to meet the needs of the youth and families, staff, community, and funders. For example, if academic improvement is a major need, include it as part of the mission of the program.

In addition to the mission statement and vision, community members should agree on program philosophy. The Cooperative Extension maintains that all quality programs need to have dimensions of youth development, education, and care. Understanding and addressing the individual needs and maturation of children and youth are also essential.

Goals, Objectives, and Program and Evaluation Design

Once the mission, vision, and philosophy are established, it is time to develop the goals, objectives, and program and evaluation designs. Several tools are available to assist with the program development effort.

One method is to develop a logic model. The logic model guides thinking around short-, medium-, and long-term outcomes as well as the inputs and outputs of the effort.

A few questions and examples that will guide the thinking include:

- What are the primary goals of the program?

- What are the specific measurable outcomes the program hopes to accomplish with and for the children and youth? (e.g., Of the 50 children in the program, 85 percent will improve their grades.)

- What program strategies will be used to meet the outcomes? (e.g., The program will offer experiential learning activities that will excite children about learning and increase their ability to learn, especially in the academic areas of which the school reports students to have the lowest achievement. Strategies include homework assistance, tutoring and mentoring, guided educational experiences via computers, and field trips that will reinforce program content.)

- How will the objectives or outcomes be measured? (e.g., The degree to which the objectives are measured will involve comparisons of school grades from the beginning and end of the year, pre-and-post-test scores on instruments specially designed to measure knowledge gain in program areas, and year-to-year improvement on standardized test scores.)

More information on logic models, including how to construct one, examples, and templates, are available from the following sites:

- 4-H PYD Academy at Extension.org: https://pyd-academy.extension.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/04_The-Logic-of-Youth-Development.pdf

- Community Tool Box, Center for Community Health and Development at the University of Kansas: https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/overview/models-for-community-health-and-development/logic-model-development/main

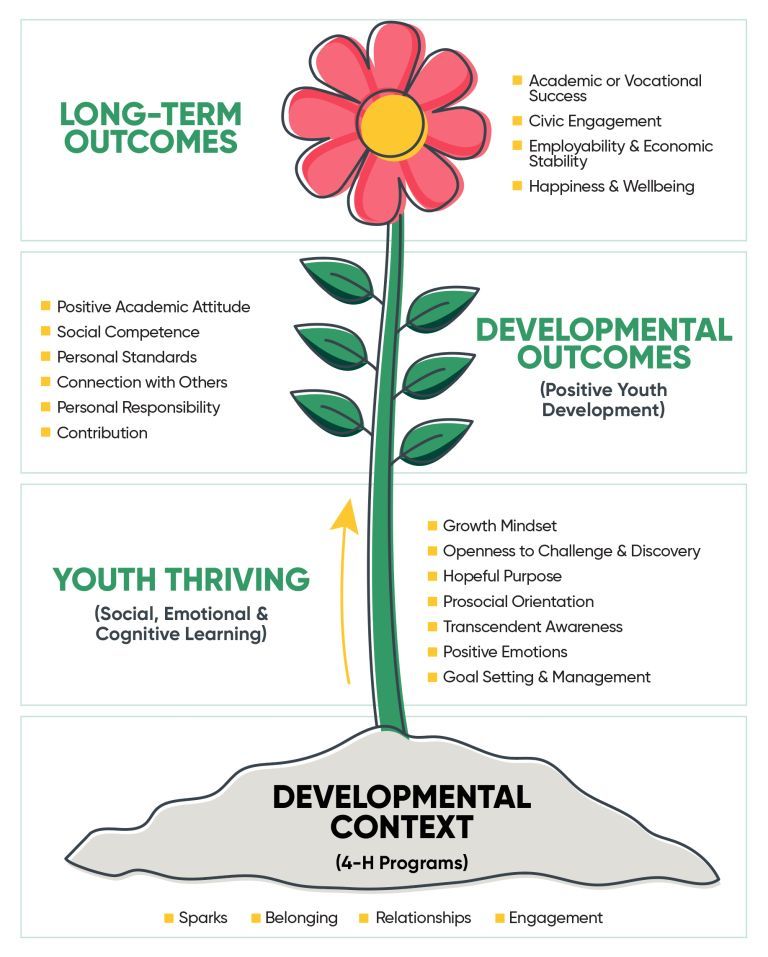

After-School Programs and Youth Development Models

Programming in the after-school hours is an effective method for delivering the 4-H Youth Development Program. In order to create quality programs, program design must account for positive youth development principles. The Essential Elements of 4-H Youth Development and the 4-H Thriving Model will help in this process.

Essential Elements of Youth Development

- A positive relationship with a caring adult. After-school programs provide a wonderful opportunity for youth to develop positive relationships with caring adults. Staff and 4-H volunteers can work with youth on an ongoing, long-term, consistent basis to develop these important relationships.

- A safe environment. 4-H professionals can help after-school staff design physical program spaces and psychological environments that are positive, respectful, and safe for youth.

- A welcoming environment. Through curricula offerings and positive environments, after-school programs provide a kaleidoscope of opportunities for youth to learn to respect and value each other.

- Engagement in learning. After-school programs provide a learning laboratory for youth to develop their cognitive, social, emotional, and physical domains. 4-H professionals provide experiential learning experiences that are core to the 4-H program and vital to igniting a passion for learning.

- Opportunity for mastery. Given the extended time youth spend in after-school programs, sufficient time exists for youth to master many skills and gain tremendous knowledge in many content areas. 4-H curricula are great resources for the mastery of several subject areas.

- Opportunity to see oneself as an active participant in the future. 4-H values youth-adult partnerships. After-school programs provide many opportunities for youth to influence people and events through their involvement in decision-making and other intentionally planned experiences.

- Opportunity for self-determination. By assisting with activity design and serving as mentors and teachers in after-school programs, youth learn leadership, citizenship, and life skills that help them mature and develop discipline and responsibility. Through planned program designs, youth learn more about their abilities and interests and become independent thinkers.

- Opportunity to value and practice service to others. After-school programs can give youth opportunities to participate in community service projects and develop citizenship skills. Enlisting the support of community resources and bringing the community to the after-school program helps youth learn about their roles in society.

4-H Thriving Model

This model illustrates 4-H positive youth development by connecting high-quality program settings with youth thriving.

The developmental context includes the following key components:

- sparks — providing a place where youth can find and explore what sparks their interest;

- belonging — creating spaces of belonging where ALL kids feel welcome and physically and emotionally safe;

- relationships — nurturing positive, supportive, and empowering relationships between youth and adults and youth and their peers; and

- engagement — challenging and encouraging youth to pursue their own learning and growth, and promoting active engagement where youth have a voice.

These set the foundation for positive youth development and should be included in program design and implementation. With this basis, the youth will have the support needed to grow and thrive. Youth thriving — that is, social, emotional, and cognitive growth — is indicated by seven factors: openness to challenges and discovery, growth mindset, hopeful purpose, pro-social orientation, transcendent awareness, positive emotionality and self-regulation, and goal setting and management.

The model includes developmental outcomes (which may be key components in program evaluations). These are a positive academic attitude, social competence, personal standards, connections with others, personal responsibility, and contribution. The summation of these factors sets the foundation for long-term positive outcomes including academic or vocational success, civic engagement, employability and economic stability, and a sense of happiness and well-being.

Credit: Helping Youth Thrive, PYD Committee

Further information on the 4-H Thrive Model, including training, resources, curriculum, and more, is available at https://helping-youth-thrive.extension.org/home/ and https://4-h.org/about/what-is-pyd/.

Chapter 4: Develop a Budget

Developing the budget puts a cost value on the mission, goals, activities, and outcomes that will be accomplished in the program. To assist in this process, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ Head Start program has a useful resource, Financing and Budgeting for Early Care and Education Facilities Guidebook, available at https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/publication/financing-budgeting-early-care-education-facilities-guidebook.

Many questions under “Establishing Governing Structures” in Chapter 3 factor heavily into budget development. The following list represents important budget development considerations:

- Number of youth to be served

- Staff-to-child ratios and number of staff needed

- Staff working hours

- Professional development costs (orientation and in-service training)

- Staff salary and benefits

- Staff recruitment and criminal background checks

- Snacks and meals

- Transportation

- Facility costs (rent, utilities, etc.)

- Liability and accident insurance

- Materials for activities and resources

- Audit

- Other

Start-Up Versus Operational Budgets

Start-up costs and operational costs need to be calculated separately. Therefore, it is important to develop two budgets — one for starting the program and one for operating it. The start-up budget should cover at least six months. You should include one-time purchases in the start-up costs, such as furniture, equipment, supplies, activities and games, building repairs, phone and internet installation, other installation costs, and any extra payment for staff time or screening needed to get the program started. When developing the start-up budget, consider obtaining in-kind donations that may help reduce the start-up costs. For example, a local business may donate computers to the program.

You might want to develop the budget based on under-projected enrollment for the first 6 to 9 months as it may take that much time for the program to reach its anticipated enrollment. Plan for inconsistent income due to enrollment variability, such as youth dropping out of the program, the length of time it will take to replace the children who leave, vacations or illnesses, and the time it will take to become fully operational. Also, it is good practice to have a waiting list.

Income Sources and Considerations

Next, you must locate sources of revenue for start-up and operational costs. There are many options for fundraising that may be applicable to different settings or circumstances. A useful tool to begin this process is The Art of Fundraising: A Practical Workbook of Tools and Strategies by EMpower (2018). This step-by-step guide offers insight and practical strategies in creating a fundraising plan for organizations.

Securing grants is one option for the first year or first several years. Find federal government options at the following websites:

- https://youth.gov/funding-search/grants-search

- https://www.grants.gov/

- https://www2.ed.gov/fund/grants-apply.html?src=pn

- https://oese.ed.gov/offices/office-of-formula-grants/school-support-and-accountability/21st-century-community-learning-centers/

Additionally, your state or district may have other local grant options. Contact your university’s grant office for Extension programs, your county and city managers, and other key agencies to see what funding opportunities are available.

In-kind support is another source of revenue. Although in-kind support may help with start-up costs, it may not meet operational costs month after month. For example, in-kind support may cover location, materials, or field trips without direct costs. However, staff salaries and other bills require sustainable monetary sources.

TIP: The Child and Adult Care Food Program administered by the United States Department of Agriculture is available to provide subsidized meals and snacks for families with limited resources. It also provides commodity foods to certain programs. This assistance can significantly reduce budgets and supply nutritious meals and snacks that are important to the healthy development of children and youth. If the after-school program is located in a school, the school may be willing to sponsor the CACFP program for the after-school program. See www.fns.usda.gov. National 4-H Headquarters Staff can also assist in linking Extension professionals to these resources.

In most programs, parents provide the majority of financial support to the program. Therefore, the cost for children to participate needs to be what families can and will pay. You can figure the cost per youth served after you determine the cost of the program based on weekly, monthly, or yearly expense estimates. The cost per youth is calculated by dividing the number of young people that will participate by the total cost. For example, if the weekly cost for the program is $750, and 15 youth are registered, the weekly cost per youth is $750 divided by 15 youth or $50 per child.

Be sure that parents understand the fee structure and attendance requirements. The program could start running a deficit if parents only plan to use the program once or twice per week, but the estimated cost of the child to use the program was calculated on attendance five days a week.

Developing a good budget is critical to the success of the program. Involve people with budget development and management expertise in the process. Before starting a program, be sure a financial sustainability plan is in place and enough full-time equivalent children and youth will participate to maintain a financially stable program.

Consider the following when developing your operational budget as it will affect the cost per child to participate:

- Is this cost in line with the needs assessment about how much parents are willing to pay?

- Does it align with similar programs offered in the county?

- Will the program be available to part-time users? How will their costs be adjusted?

- Is there a registration fee? Will the rate be reduced for early registrations?

- Will limited-resource families be able to participate in the program? Are scholarships available?

- Will a sliding fee scale for families with multiple children and/or limited-resource families be available?

- Will fee penalties for late pickup or early drop-offs be assessed?

- Will a fee for late payments be assessed?

- Will fees for youth who do not attend because of sickness or family vacations be refunded?

- Can some costs be reduced or eliminated from the budget?

- Are funds available from state or federal agencies that can help subsidize the cost of the program?

Chapter 5: Write Policies and Procedures

Another critical step in program development is the composition of policies and procedures for your program. Staff who already operate programs are a great source for ideas. Identifying and articulating the policies and procedures before starting the program will help reduce misunderstanding and confusion once the program begins.

You will need to write specific policies and procedures around these areas:

- Staffing (front-line, food service, janitorial/maintenance, administration, etc.)

- Fee collection (how much, when due, penalty for late payment, etc.)

- Discipline

- Drop-off and dismissal

- Attendance requirements and documentation

- Participants check-in and check-out

- Schedule posting (for staff and students)

- Daily operation

- Insurance coverage

- Off-site activities

- Parental visitation

- Snacks and meals

- Missing youth

- Licensing requirements

- Child protection screening/Criminal background checks

Consider all aspects of the program and develop appropriate policies to ensure the safety of the participants and staff. Each item listed above must have an outline of very specific procedures including budget implications.

The following university sites offer examples of youth program policies and procedures, including checklists for starting programs, compliance and incident reporting, codes of conduct, waivers and medical authorization, and other useful templates, tools, and information. Although these may serve as a reference, it is essential that you check with your university for applicable forms and state requirements.

- The University of Iowa: Youth Programs Manual, https://provost.uiowa.edu/sites/provost.uiowa.edu/files/2020-12/Youth_Programs_Manual.pdf

- Michigan State University: Operational Requirements For Conducting University Youth Programs, https://hr.msu.edu/policies-procedures/university-wide/youth_program_operation.html

Chapter 6: Put a Staff in Place

Staff play an essential role in after-school programs. Research shows that the quality of staff greatly affects the outcomes for youth in the program. (See Appendix, pages 39–42.) Therefore, staffing decisions are extremely important. A staffing plan should include, but is not limited to, salary, benefits, recruiting, orientation, training, professional development, performance evaluation, and recognition.

When creating your staffing plan, you must do the following:

- Budget for recruiting and training staff.

- Hire qualified staff and pay a good salary.

- Offer benefits if possible.

- Ensure a quality work environment for staff.

- Keep staff-to-child ratios as low as possible. (The ratio should be 1 to 15 or lower if the audience being served requires more supervision and support.)

- If the state requires a license for the program, be sure to check the requirements before finalizing the budget. Staff with specialized qualifications may require higher salaries.

- Provide opportunities for salary adjustments.

- Develop a staff handbook and provide orientation for all staff.

- Provide opportunities for professional development and/or training for staff.

- Conduct regular staff evaluations.

- Develop a plan for substitutes when staff must miss work, especially for unexpected absences due to emergencies.

You should also consider the following in a staffing plan. Include committee members when researching the answers to these questions:

- What recruitment strategy will be used to find staff?

- What are the minimum qualifications for staff (education, experience, age, etc.)?

- Who will hire staff?

- What is the supervisory structure for the program? Who supervises the director?

- Will background checks (criminal and/or other) be made? If so, how will costs be covered, and who will conduct them?

- Who will develop the staff application?

- Who will interview staff?

- What questions will be asked in the interview process? Who conducts the interviews?

- Do all staff have written job descriptions, including volunteers?

- What is the evaluation plan for staff?

- What is the staff development plan?

- Has a staff handbook been developed? Who develops the handbook?

- Will staff be paid for planning time, additional education, and professional development meetings? How much time is allocated for each?

- Who conducts the staff orientation? How long does it take? What is the content of the orientation?

- How often will staff meetings be held?

- Will the cost of membership to professional organizations be covered for staff?

- What educational resources and reference materials will be available to staff?

Develop a Staff Manual

You should develop a manual for salaried and volunteer staff members who give significant time to the program. The staff manual is a valuable communication tool and will help minimize misunderstandings. Include these topics in your staff manual:

- Program mission and goals

- Job descriptions and expectations of each staff member

- Any probationary requirements

- Attendance requirements

- Staff conduct and policies regarding smoking, drugs, alcohol, missed work, and other policies governing the behavior of staff

- Grievance policies

- Discipline policies

- Supervisory structure

- Risk management plan and dealing with emergencies

- Administration of medicines to children and medical emergencies

- First aid procedures and location of supplies

- Record-keeping requirements

- Administration of snacks and meals

- Accident and incident reports

- Check-in and check-out procedures (Who is authorized to sign children out?)

- Fee structure and record-keeping

- Payment processing procedures (receipts, transfer forms, deposit, etc.)

- Purchase procedures, including use of petty cash

- Work schedules

- Staff benefits, including leave policies, jury duty, voting time, additional education and professional development support, and other available benefits

- Use of substitutes

- Planning time

- Staff meetings

- Evaluation plan

- Termination policy

Not all staff in a program will need or perform every function listed above. However, all staff must have a working knowledge of all procedures and policies. Staff members — even the program director — will miss work from time to time. Other staff members must be qualified to fill the void.

As always, check with your university for specific requirements and policies. For example, the University of Florida has mandated Youth Protection Training for anyone working with minors. They provide staff/volunteer training modules, background checks, and parental consent templates at https://youth.compliance.ufl.edu/protection-requirements/youth-protection-training/. Every university will have its own resources, so check with your institution first to ensure compliance.

Additionally, general resources can be found at the following sites:

- The National Afterschool Association (NAA), www.naaweb.org

- The University of North Carolina’s Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, www.fpg.unc.edu/~ecers/

These provide a wealth of information about staff qualifications, training, evaluations, and more. The NAA also can link you to your state’s affiliate after-school associations in most of the country. Other useful examples and resources are linked throughout this manual and in the Resources section (see pages 45–46).

TIP: Extension professionals can play a vital role in training after-school staff on many topics such as positive youth development concepts, experiential learning, or health and nutrition.

Chapter 7: Keep Detailed Records

Keeping good financial and programmatic records is imperative. Some of the records you must keep include:

- Enrollment forms that provide details on each child and staff member (i.e., medical information, emergency contacts, authorization forms to seek medical help if needed, authorization forms for who can pick the child up from the program, media waiver, liability waiver, etc.)

- Attendance forms

- Health forms for youth and staff

- Accommodation plans for youth and staff

- Accident reports

- Financial records of income such as fees, registration, and so forth

- Financial records of expenditures that detail how funds are used

- Reports of child abuse and neglect

- Personnel files on all adults (staff and volunteers) working with youth

- Evaluation records of staff and volunteers

For examples and templates, see the following sites, as well as others referenced throughout this manual and in the end reference section.

- University of Iowa: Youth Programs Manual (including media waiver and release, medical authorization and insurance information), https://provost.uiowa.edu/sites/provost.uiowa.edu/files/2020-12/Youth_Programs_Manual.pdf

- University of Florida: Liability Waiver, https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fyouth.compliance.ufl.edu%2Fmedia%2Fyouthcomplianceufledu%2Fdocuments%2FTemplate-Non-UF_on-Campus_Participant-Consent-Release-and-Waiver_minor.docx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK

- Oregon State University: Incident Reporting (including accident and injury report and child abuse and neglect report), https://hr.oregonstate.edu/benefits/workers-compensation-resources/incident-reporting

- Afterschool Alliance with Utah State University: Field Trip Form and Pick Up Authorization, https://www.afterschoolalliance.org/utah4hafterschoolguide.pdf

Chapter 8: Create a Parent Handbook

Another useful tool in an after-school program is a parent handbook because it will eliminate surprises to parents involved in the program. The handbook should provide parents with all the information they need to fully understand the mission, goals, philosophy, operating procedures, and policies of the program.

Remember that, in addition to the children and youth in the program, parents are customers, too! They have a right to know what to expect from the program, and the parent handbook is one way to achieve this goal.

The handbook should be presented to parents during an orientation session. Explain each section of the handbook to the parents and answer their questions. The more information the parents have at the beginning, the better the experience will be for everyone involved. In addition to many of the previously mentioned sites and resources that can help in different stages of the process, the YMCA of Southwest Florida’s Parent Handbook provides a straightforward and clear example at https://openy-skyfamilyymca.y.org/sites/1335-openy-skyfamilyymca.y.org/files/2021-07/BASE%20Parent%20Handbook.pdf.

Include these topics in the handbook:

- Program goals, mission, and philosophy

- Program administration

- Staffing design and staff qualifications

- Program location(s)

- Hours of operation

- Admission policies and procedures

- Registration and program fees and policies for refunds

- Other fee-related policies

- An enrollment contract and procedures to change the contract, if permitted

- Medical and health information requirements

- Administration of medicine and other health monitoring procedures

- Risk management plan and emergency procedures

- Discipline policy

- Snacks and meal policies

- Transportation to and from the program

- Off-site activities

- Check-in and check-out policies and procedures

- Termination notice requirements

- Subsidy support for families, if available

- Daily activities and schedule of events

Chapter 9: Get the Word Out

Now that everything is in place, it is time to let everyone know about the program. How will parents know the program is available? How will the community know what the program is doing? How will funders know their contributions are producing results? You will need to get the word out using short-term and long-term marketing plans. These suggestions are just a few of the ways you can let the community know about your program:

- Encourage announcements and sharing from parents, school personnel, partner agencies, youth development professionals, and so forth

- Contact local newspapers and radio and television stations.

- Send announcements home in school materials.

- Mail or email letters to parents.

- Put contact information in the needs assessment.

- Make telephone inquiries.

- Place flyers, posters, or banners where parents will see them.

- Present at faith-based groups or civic organizations.

- Place an article or ad in organizational newsletters, on websites, or other sources for information disseminated by groups.

- Use social media to share flyers.

- Create an event sign-up on a platform with local reach.

- Design participant and staff shirts, hats, water bottles, and so forth with the program logo and name.

- Offer incentives!

Offering incentives can help promote sharing and recruitment. For example, registration discounts or sweepstakes entries for prizes can create excitement and encourage families to register early, share on social media or with friends, and so forth. Although these offers may incur small financial impacts, they can help reduce direct advertising costs. Therefore, they should be managed in a way that does not create an additional expense from what was planned in the advertising budget.

Remember to contact everyone who expressed an interest in your program during the needs assessment process. Try to get commitments, such as paid registration fees, before opening the program. Although some parents express an initial interest in the program, plans or circumstances may change prior to the start.

The University of Maryland Extension has a plethora of information and resources for Marketing Plans at https://extension.umd.edu/resources/agribusiness-management/management/marketing-plans/. The information can help you learn to create a marketing outline, design your plan, test and track your plan, and understand other integral aspects of the process. Using resources compiled from a number of Cooperative Extension universities, additional information on marketing basics, which include strategies, attitudes, plans, and implementation, is available from the University of Maine Cooperative Extension at https://extension.umaine.edu/business/library/marketing/. Official 4-H branded marketing materials are available at https://4-h.org/resources/professionals/marketing-resources/.

Chapter 10: Evaluate Your Program

Program evaluation is an essential step in the planning process. Evaluation — the process of determining whether a program is achieving desired results — is an important element throughout the process of establishing community-based after-school programs. Your first evaluation comes when you analyze the needs assessment to determine if the need in your community is sufficient to move forward with the program. As the program is implemented, the board and staff should conduct a process evaluation that continuously seeks input from the children, parents, and community stakeholders regarding their satisfaction with the program.

It will tell you if the program is being implemented as planned to answer questions like these:

- How many children do you serve?

- Did you carry out the activity as planned?

- Were participants satisfied with the activity? Why or why not?

An outcome evaluation focuses on short-term changes in knowledge, behaviors, attitudes, or beliefs. It assesses immediate changes that might have occurred that are correlated with participation in the program. An impact evaluation examines longer-term improvements in the quality of life of children, youth, families, or community members.

Steps for conducting an evaluation typically include the following:

- Planning the evaluation

- Collecting data

- Analyzing and interpreting the data

- Communicating results to stakeholders

- Continuously improving the program

Plan Your Evaluation

Plan the evaluation while you develop goals and objectives for the program. Keep these goals and objectives quantifiable so success can be measured!

The planning process typically includes the development of a logic model (see Chapter 3). Logic models concisely show how programs are designed and expected to make a difference for children, youth, families, and communities. The logic model is the basic framework for your evaluation.

When planning the collection of data, be sure that your evaluation design and data collection instruments have been tested for validity and reliability and will measure the youth outcomes stated for your program. Determine what kinds of information can be realistically and accurately collected, as well as the best methods for collecting the information. Collection methods include written surveys, individual or group interviews (i.e., focus groups), observations, or already existing data, such as school and health records.

Observation tools designed for use in after-school and youth development programs are listed in the Suggested Evaluation Resources at the end of this chapter.

Analyze the Data

Analyzing and interpreting results can be simple or more complex, depending on the evaluation’s design and the type of information that has been collected. In some cases, it is advisable to have someone with statistical expertise conduct the data analyses. In other cases, data analysis may be as simple as using a spreadsheet to calculate descriptive statistics such as the mean or average, frequencies, or percentages. Analyze qualitative data like stories, observations, or interviews by coding for common themes. A variety of software packages will analyze quantitative and qualitative data.

Communicate the Results

Communicating the evaluation results is another important step in the process. Present your findings in a format that is easily understandable to a broad range of stakeholders — parents, funders, staff, and many others. Depending on the audience, objective, and other factors, communication methods can consist of formal reports, newsletters, websites, presentations, or other, more informal, briefings with stakeholders.

Include the following information in communications with stakeholders:

- Purpose and context for the evaluation

- Evaluation questions asked

- Evaluation activities designed to answer those questions

- Types and quality of the evaluation data collected

- Findings

- Recommendations

Continue Improvement

By focusing on continuous program improvement, the evaluation process becomes part of a cycle. Results are used to identify program strengths, define areas for improvement, and modify or refine goals, objectives, and outcomes.

Suggested Evaluation Resources

Many resources exist to assist with developing an appropriate evaluation plan and selecting instruments and methods to measure the stated objectives.

- Children, Youth, and Families At-Risk equips CYFAR Sustainable Community Projects with the skills to build, deliver, evaluate, and sustain programs. www.cyfar.org

- N. C. Cooperative Extension Program Evaluation provides tools, frameworks, and approaches to evaluations. https://evaluation.ces.ncsu.edu/program-evaluation/

- Innovation Network offers evaluation and capacity-building tools. https://www.innonet.org/news-insights/resources/category/evaluation-capacity-building/

- 4-h.org has a variety of resources including evaluation tools for 4-H projects and programs. (Note that gaining access to Common Measures requires signing in.) https://4-h.org/resources/professionals/common-measures/

- Youth.gov offers a Youth Involvement and Engagement Assessment Tool. https://www.youth.gov/youth-topics/positive-youth-development/how-do-you-assess-youth-involvement-and-engagement

- EMpower shares Youth Development Tools and Resources. https://empowerweb.org/youth-development-tools

- The University of Connecticut and the State of Connecticut Office of Policy and Management offers guidance in Assessing Outcomes in Youth Programs: A Practical Handbook, which is designed to help managers and staff plan evaluations of youth programs. http://www.ct.gov/opm/LIB/opm/CJPPD/CjJjyd/JjydPublications/ChildYouthOutcomeHandbook2005.pdf

- The University of North Carolina’s Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute created The School-Age Care Environment Rating Scale, which provides observational instruments designed to assess group care settings for children. https://ers.fpg.unc.edu/

- The University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension Program Development and Evaluation website includes logic model worksheets and templates, information about human subjects’ protection, instruments, and much more. https://fyi.extension.wisc.edu/programdevelopment/

- W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s Step-by-Step Guide to Evaluation provides a framework for thinking about evaluation as a relevant program tool. https://wkkf.issuelab.org/resource/the-step-by-step-guide-to-evaluation-how-to-become-savvy-evaluation-consumers-4.html

Chapter 11: Sustain Your Program

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, sustainability is “the quality of being able to continue over a period of time.” For after-school programs, a sustainable program delivers intended services to their targeted audience and achieves their goals and objectives over time (Marek et al., 2003). Continuing to meet program goals is key; flexibility and adaptations, such as activity or schedule modifications, leadership changes, and so forth may be necessary to achieve this.

The Afterschool Alliance (2023) notes the following critical components in developing a sustainable program:

- Leadership and program vision

- Collaborative partnerships

- Community engagement

- High quality program and proven results

- Diverse funding sources

- Support from school administration/other key champions

- Previous experience with after-school or summer programs

Collaborate, Collaborate, Collaborate!

Where should Extension professionals begin? First, you must understand that strong relationships among collaborators and program participants influence sustainability factors. Frequently underestimated, collaborations are an approach where all stakeholders are valued (Jakes, 2005). It is often effective to form a governing board. (See pages 18–19.) The community collaborative approach, with representation from target populations — including youth — improves the likelihood that

- “buy-in” is established prior to program implementation,

- programs will address key community needs,

- collaborators will assume meaningful leadership roles, and

- successful marketing plans will be created and implemented — the most common reason programs report increases in the number of volunteers.

Programs that provide meaningful involvement of collaborators may be better equipped to overcome common obstacles in sustaining programs such as lack of funding, staffing difficulties, and limited community resources.

Prior to implementing a program, address the following:

- Is funding available long-term (for at least 2 years)?

- Do you have plans in place for obtaining additional funds?

- Are staff involved in program design, evaluation, and decision-making?

- Are staff recognized and rewarded for their work?

- Are community collaborators willing and able to provide materials/equipment, space, in-kind support, and personnel who can help with program implementation?

Note: Refer to Chapter 4 and the Resource list at the end for funding options that may help with program continuity.

An excellent resource is available from the Afterschool Alliance at https://www.afterschoolalliance.org/documents/RoadtoSustainability(1).pdf. This workbook offers a roadmap, tools, planning sheets, tips, and resources to guide you step-by-step in creating a sustainability plan for your program.

Conclusion

Across the nation, 24.6 million kids would participate in after-school programs if one were available to them (Afterschool Alliance, 2020). CES has been working hard — in collaboration with other agencies and organizations — to make after-school hours a time of opportunity for youth across the United States by increasing the quality and quantity of after-school programs.

4-H professionals have been very effective at helping to improve the quality of existing programs and establishing new after-school programs. This resource guide is designed to help CES professionals provide leadership and support to communities as they determine whether a need for after-school programs exists and, if so, how to meet the identified needs.

Extension, however, cannot do it alone. Community partners must come together to achieve the goal. Through collaboration, CES professionals can help create safe, fun, educational, and enriching environments for youth. These programs will help eliminate many of the problems associated with youth who are home alone and create opportunities where youth can gain the many benefits associated with quality, adult-supervised, after-school programs. Through 4-H Afterschool programs, Extension personnel work hard to train after-school staff, develop quality programs, infuse experiential curricula, and create after-school communities of children across America who are learning leadership, citizenship, and other essential life skills.

Quality after-school programs impact the educational, economic, employment, and environmental conditions for children, youth, and their families. They are everyone’s business, and everyone benefits!

Appendix

Benefits of After-school Programs

After-school programs have expanded and developed in recent years as the importance of quality youth programs has become widely recognized and supported. The current body of research makes a case that youth benefit from consistent participation in well-run, quality after-school programs (American Institutes for Research, 2015). Moreover, the positive outcomes in individuals are often correlated across the domains of socio-emotional, behavioral, and physical health, since these are interconnected within an individual (Sparr et al., 2021). These factors are associated with broader benefits such as learning strategies and academic performance, as well as life and career skills. The questions researchers, practitioners, and policymakers should address are “not only whether particular programs are helping youth, but also how they are helping and how they could help more” (Deutsch et al., 2017). Thus, the integration of research and practice can help continue to improve the field and further serve the youth involved.

Evidence-Based Practices for After-School Programs

Research supports the contention that youth who participate in structured activities are better off than those involved in unstructured activities. For example, Barkto & Eccles (2003) found significant differences in adolescents’ academic performance, behavior, and mental health across activity domains, with the most benefits noted in those participating in organized and structured activities. While adolescents are gaining independence and may not always require adult supervision, it is important to note that structured out-of-school activities still provide various benefits for many youth.

Positive results are also seen in younger children. Sparr and colleagues (2021) conducted a literature review of 52 after-school programs for elementary-age children to determine trends and effectiveness. They found the following positive results:

- Fifty percent reported at least one social-emotional outcome, such as social skills, self-confidence, growth-mindset, physical and emotional safety, and so forth. These include multiple types of after-school programs.

- Fourteen percent reported behavioral outcomes, such as reduced disruptive behaviors, preventing risk behaviors, and improving mental health. These were most often in conjunction with improvements in social-emotional factors.

- Thirty-seven percent reported physical health outcomes, such as overall physical health, eating attitudes and behaviors, and physical activity. These programs were often designed with a physical health focus.

Overall, programs reporting positive outcomes tend to have several common characteristics: clear goals, intentional design, age-appropriate curriculum or interventions, and a focus on individual needs. These findings are consistent with other studies discussed in this appendix.

Participation