Abstract

This article provides an introductory overview of how computers analyze images using artificial intelligence (AI) and computer vision. To illustrate the concepts, we use mushrooms as an example case for object detection. Computer vision is how computers can "see" and interpret pictures. The process includes collecting images, examining pixels, finding edges, and recognizing shapes and patterns. The article compares two methods for this task: traditional image processing, which follows fixed rules, and modern machine learning. In machine learning, the computer is trained with labeled examples, learns patterns from them much like a human would, and then applies those patterns to recognize new images. Both methods have strengths and limits when used in agriculture. Although mushroom detection is used for demonstration, the goal of this article is to help readers understand how AI-based image analysis supports broader agricultural and environmental applications. A glossary of computer vision terms is provided at the end of the article to assist new readers.

Introduction

A computer vision system (Ballard and Brown 1982) is a branch of artificial intelligence (AI) that helps computers understand pictures and videos. AI refers to a computer’s ability to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as recognizing patterns or making decisions. Computer vision systems use vision sensors (such as color cameras) to "see" the world and AI software programs to analyze what is captured in the pictures. For example, in agriculture, a computer vision system looks at images of fruit and determines if the fruit is ready to be picked by checking its color and shape, or finds diseased plants by spotting visual signs of disease. Robots (automated machines that can perform physical tasks) can use computer vision technology to find and pick crops in the field (Ajith et al. 2025; Hou et al. 2023; Tian et al. 2020). In this article, we explain how AI enables computers to see and understand images. The article describes how computers can gather images, prepare them for use, and learn to recognize different objects, with examples of how computer vision can be applied in real life, especially in agriculture. To demonstrate these concepts, we use mushroom detection evaluation as a practical example of how AI enables computers to analyze and interpret images. Although this article uses mushrooms as a simple example to illustrate how computer vision works, it can be applied across many crops and production systems to reduce labor needs, improve consistency, and support timely decisions.

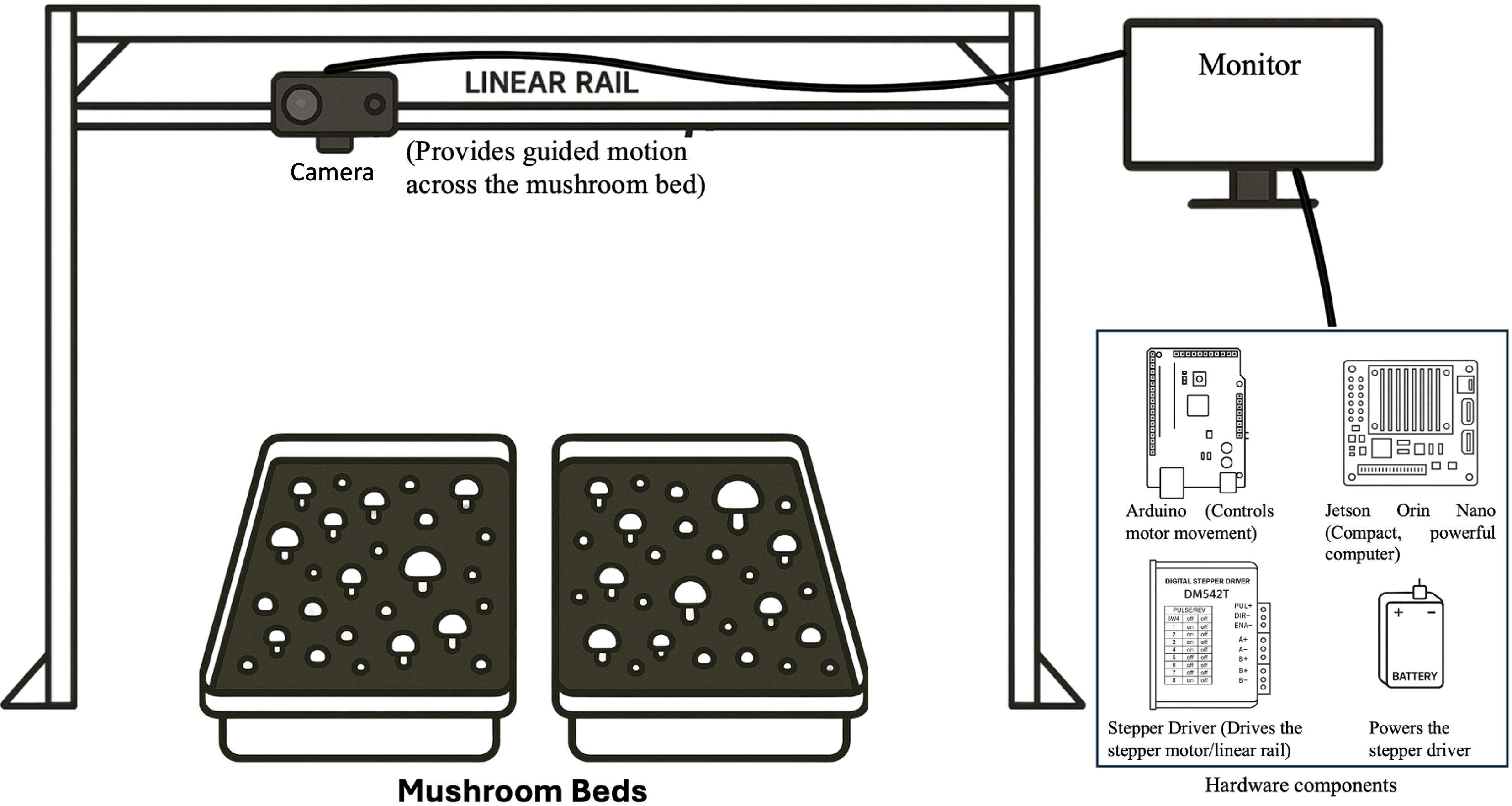

Major Components of a Computer Vision System

A computer vision system is made up of several key parts that work together. First, there is a camera that takes pictures or videos. These images are sent to a computer or special device for processing. Then, a monitor or screen displays the results. Some systems have extra hardware, such as sensors to collect more information from the environment, or motor controllers to help the system move and interact with things around it. The system also runs software, including the operating system, programs for collecting and preparing images, and code that helps the computer make decisions and controls its actions. Figure 1 shows an example of what a computer vision system might look like.

Example of a Computer Vision System

Credit: Namrata Dutt, UF/IFAS GCREC

Understanding Digital Images: The Foundation of Computer Vision

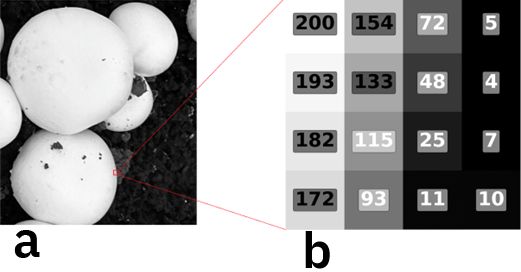

Computer vision is a tool that helps machines understand pictures. When we look at a picture, we notice things such as objects, colors, and ways different parts fit together. Computers see images differently. They process each picture as a collection of digital data. This means they use numbers to show how bright or dark each part of the image is. A pixel is the smallest unit of an image, arranged like a grid, and each pixel is assigned a number that stores its color information. For example, in a grayscale picture, every pixel has a value from 0 (which is black) to 255 (which is white). Figure 2 shows how this works.

Credit: Namrata Dutt, UF/IFAS GCREC

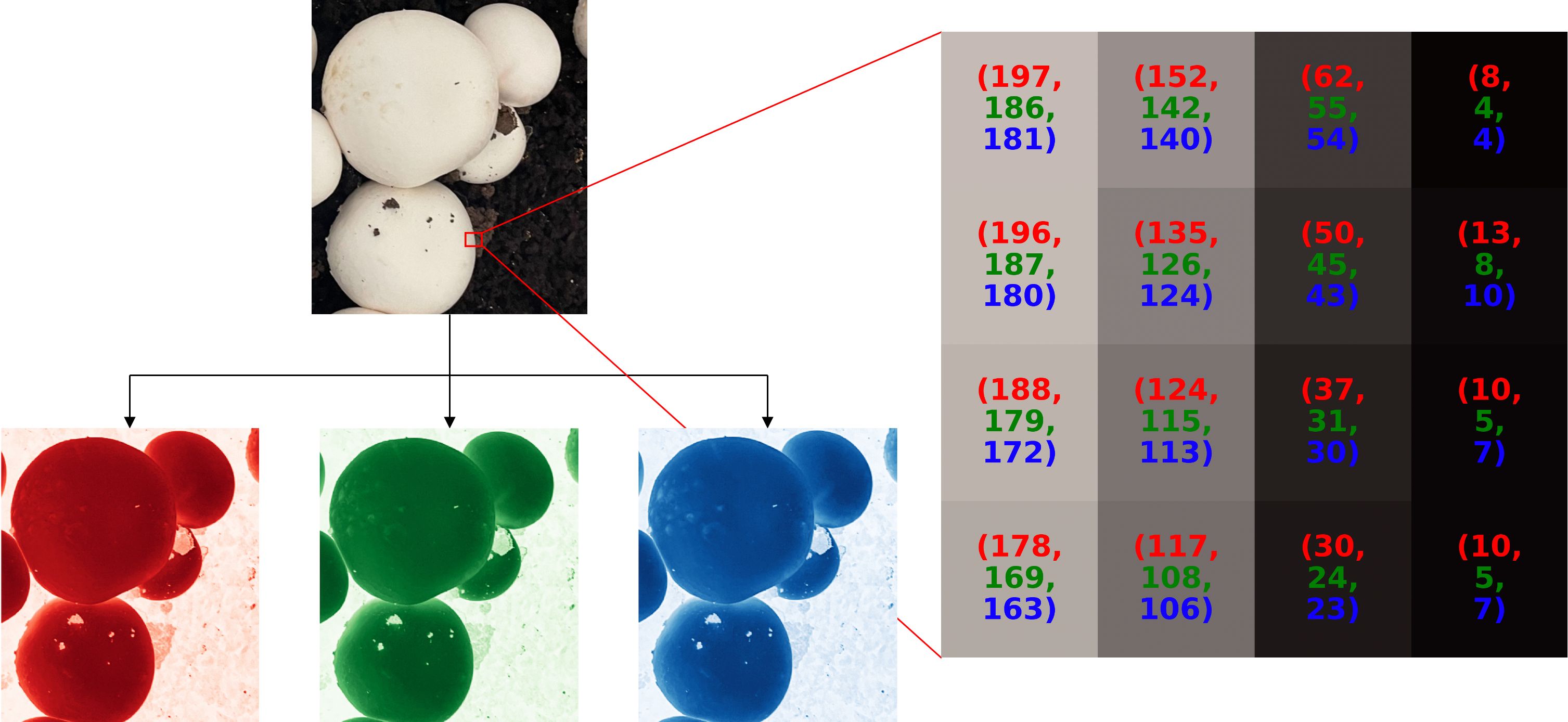

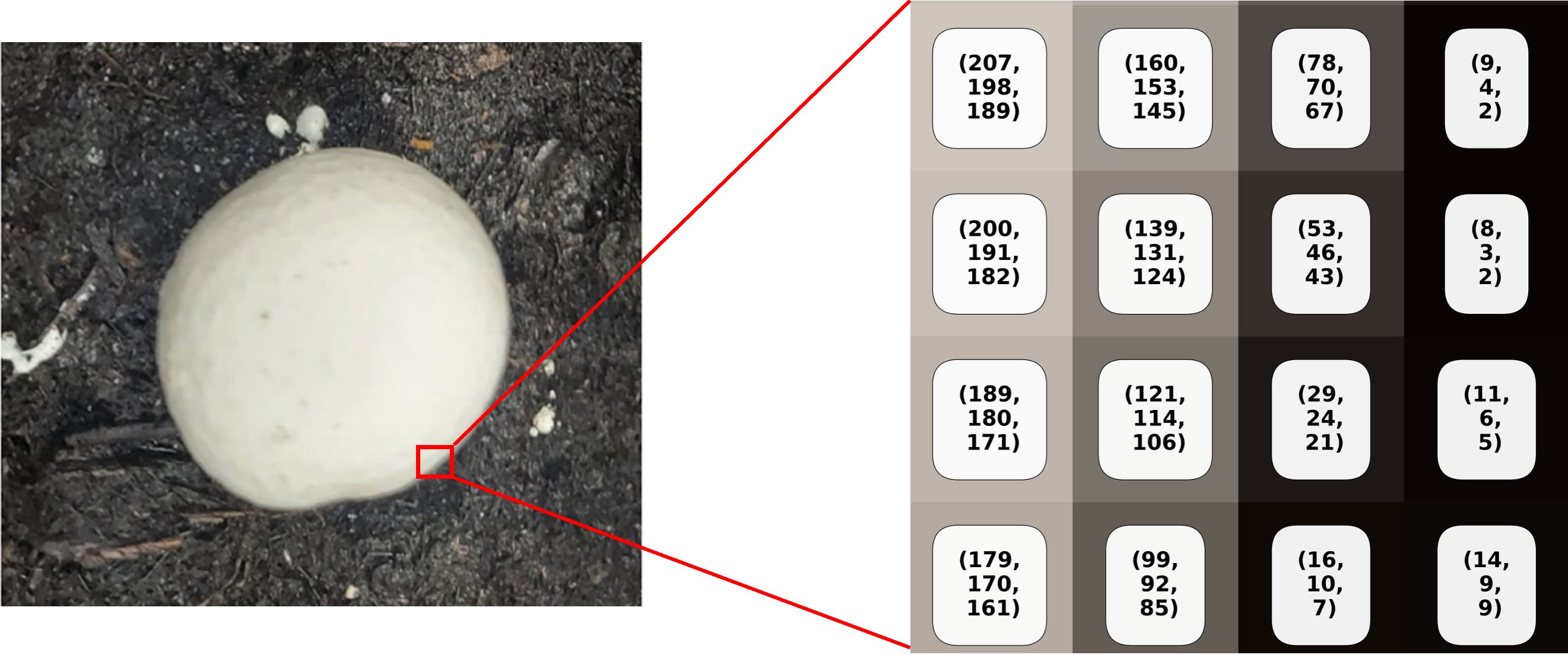

Color images work a little differently. Each pixel has three values: red (R), green (G), and blue (B). By mixing different amounts of R, G, and B, a computer can reproduce any visible color. This is called the RGB color model. Figure 3 uses an example of mushrooms to show how an RGB image is created by combining red (R), green (G), and blue (B) color channels.

Credit: Namrata Dutt, UF/IFAS GCREC

For example, (255, 0, 0) makes pure red, (0, 255, 0) makes pure green, (0, 0, 255) makes pure blue, (255, 255, 255) makes white, and (0, 0, 0) makes black. An algorithm is a set of step-by-step instructions that a computer follows to do a job. Image processing algorithms then convert this raw data into meaningful information, allowing the system to identify what is in the scene.

Background

In a digital image, each pixel has three color channels (red, green, and blue) as a number between 0 and 255. This format, written in parentheses, follows the standard RGB color notation used in computer science, where each number represents the intensity of red, green, and blue channels, respectively. The number range comes from the way computers store data: one byte consists of 8 bits, where 00000000 represents 0 and 11111111 represents 255. These numbers control how bright a color looks. A value of 0 means no color, while 255 means full brightness. By mixing red, green, and blue values, a pixel can make over 16 million colors.

Image Processing

To show how this works for mushroom detection, let us think about how a computer might find circles, like the cap of a mushroom. Since images are just grids of numbers, the computer looks for circle shapes by following these steps.

- Finding edges: The algorithm scans the grayscale image to find sudden changes in brightness. For example, a white mushroom cap against a dark soil background creates a clear boundary, where bright pixels from the mushroom are placed right next to dark pixels from the soil. By comparing nearby pixels, the algorithm marks these changes as edges. It then draws the outline of each shape in the picture, such as the boundary of a mushroom shown in Figure 4.

Credit: Namrata Dutt, UF/IFAS GCREC

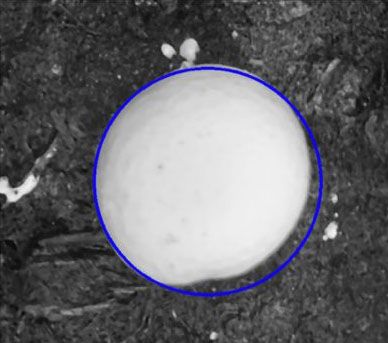

2. Searching for circular shapes: Once the edges are found, the algorithm looks for circles of different sizes and positions. Each edge pixel "votes" for the circles it might be part of. The circles that get the most votes are picked as the best matches. Figure 5 shows some examples of these possible circles.

Credit: Namrata Dutt, UF/IFAS GCREC

3. Confirming the best matches: The computer gives each circle a score based on how well it matches the detected outlines. Only circles with a high score are kept, removing false matches like shadows. Figure 6 shows the circle that best fits the mushroom.

Credit: Namrata Dutt, UF/IFAS GCREC

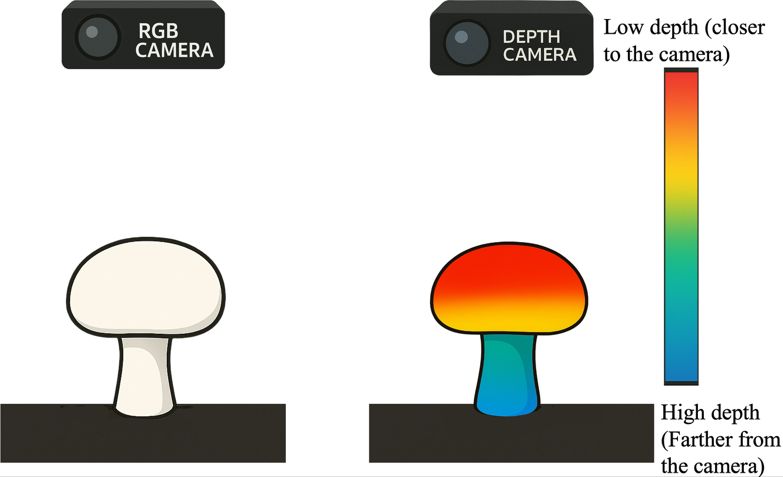

Finding circles is just one way to detect mushrooms. Circle-finding algorithms require adjusting many parameters, such as the smallest and largest circle sizes to search for, and the number of circles they need to detect. Because of this, they work best in simple and fixed environments with few varying factors. On real mushroom farms, mushrooms often grow close together and are not perfect circles, so this method alone is not always accurate. Using several different methods together can help the computer find mushrooms better. Adding 3D information can help even more. A depth camera (Lee 2012) can capture the mushroom's shape, since mushrooms are higher in the middle and lower at the edges. This 3D shape information makes it easier to tell mushrooms apart. Figure 7 shows how depth images give 3D information that can be used to measure mushroom height, shape, and separate mushrooms to improve detection.

Credit: Namrata Dutt, UF/IFAS GCREC

While traditional image processing (Kovasznay and Joseph 1955) works well in simple settings, real fields often have shadows, visual obstructions, and changing light. These problems make it hard for fixed rules to work. In these cases, we use machine learning, which lets the computer learn from the data itself and become better at finding objects, even in suboptimal conditions.

Machine Learning

Machine learning (Carbonell 1983; Mane et al. 2017) allows computers to learn from data and make decisions without needing strict rules. Instead of just following instructions, a machine learning model studies the examples, finds patterns, and gradually improves its predictions by training.

How Does Machine Learning Work?

1. Training Dataset

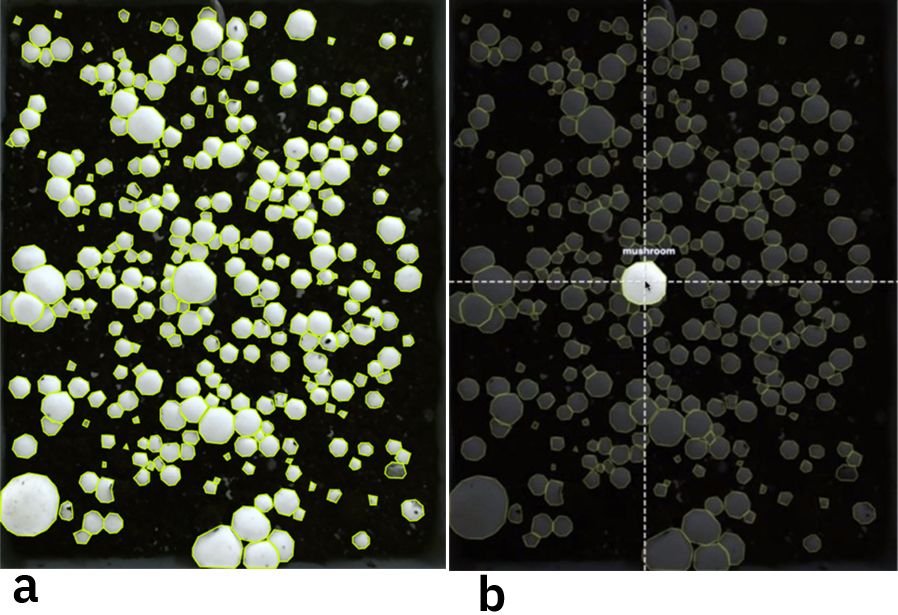

A machine learning model learns from thousands of labeled examples. For mushroom detection, human experts outline each mushroom’s boundaries and mark it as "mushroom" (Figure 8). The dataset should include different pictures of mushrooms with different sizes, shapes, lighting conditions, and backgrounds. This helps the model learn to find mushrooms in various situations.

Credit: Namrata Dutt, UF/IFAS GCREC

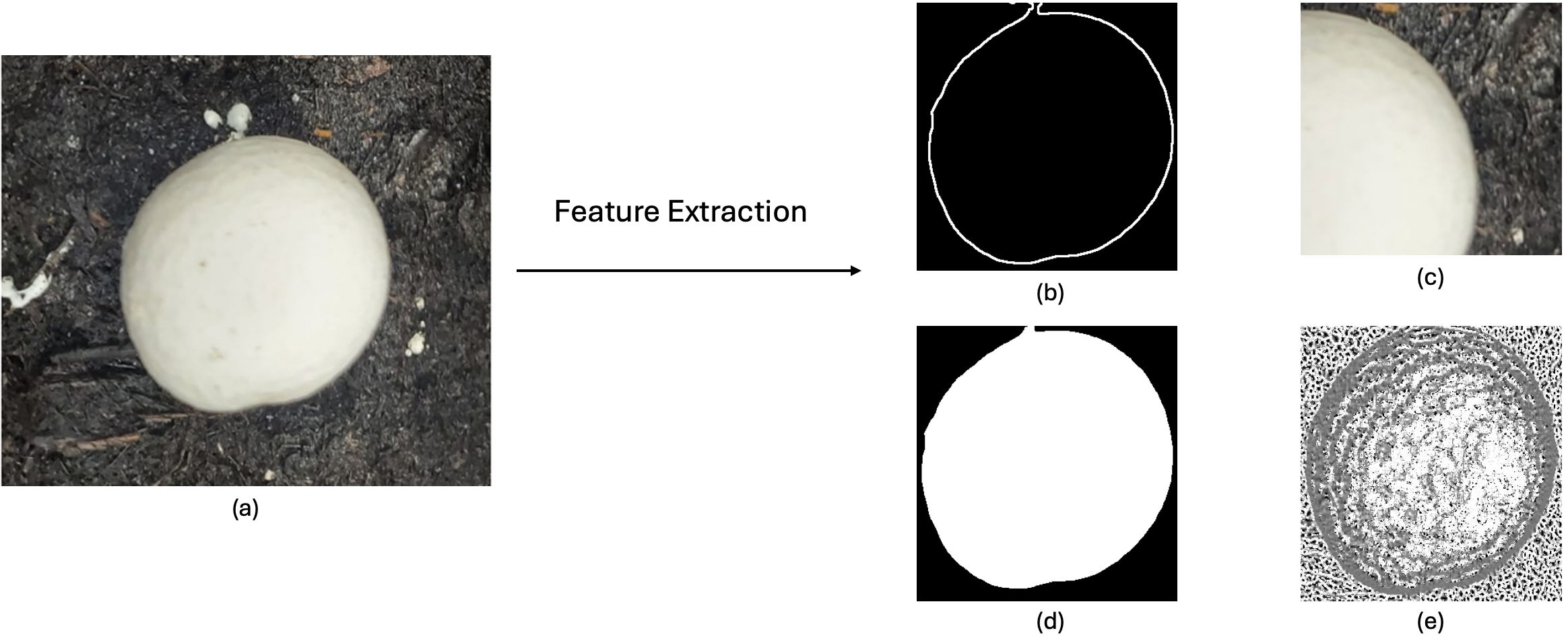

2. Feature Extraction: Finding Important Information

Raw images are turned into computer-readable features such as edges, colors, textures, shapes, or depth. These features help the model tell objects apart. Figure 9 shows the features taken from a mushroom (e.g., a mushroom's round shape or spotted cap).

Credit: Namrata Dutt, UF/IFAS GCREC

3. Model Training: Learning Patterns

The model starts by making random guesses about patterns in the data. It compares its guesses to the correct labels and changes its rules to reduce mistakes. After repeating this many times, the model learns to link certain features (such as mushroom texture) with the mushroom label.

4. Testing and Improving the Model

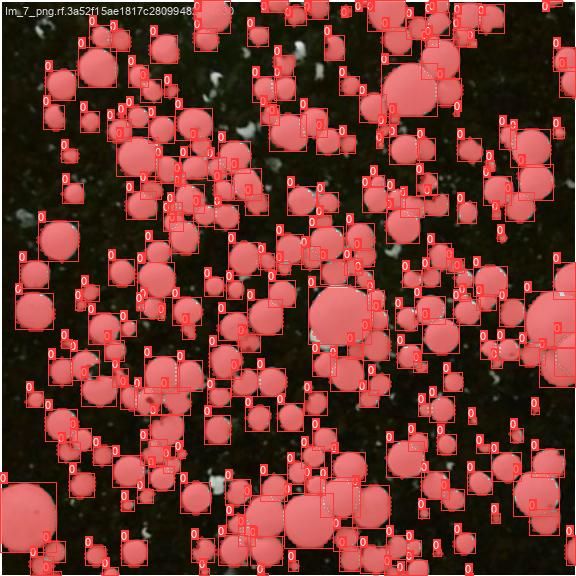

Once the model is trained, it is tested on new images it has not seen before. If it makes mistakes, like confusing a mushroom with another object, developers can retrain the model to improve accuracy. Figure 10 shows the model's results after these changes, when it predicts correctly on new data.

Credit: Namrata Dutt, UF/IFAS GCREC

Observation

Figure 10 shows two types of results from the machine learning model. The first is object detection, where each mushroom is marked with a red box that indicates the general location of the mushroom. The second is segmentation, where each mushroom is highlighted in red shade (called a “mask” in computer vision), showing the mushroom's exact shape, pixel by pixel. Detection offers a quick overview of where the mushroom is located, while segmentation provides a more detailed outline.

5. Optimization: Improving the Model

The final model is tuned to balance speed and accuracy. Programmers remove unnecessary steps, so the model learns real patterns instead of just memorizing examples. Depending on the goal, the model can be made to work in real time (e.g., on a farm robot or smartphone) or for maximum accuracy (e.g., in medical imaging). In every case, the model should work well in different field conditions.

With the basics of image processing and machine learning covered, Table 1 summarizes their strengths and limits for easy comparison.

Table 1. Comparison of image processing and machine learning.

Conclusion

Both image processing and machine learning offer unique advantages for mushroom detection. Image processing is efficient and effective when environmental conditions are stable, quickly separating mushrooms from the background. However, it can struggle when mushrooms cluster closely together or when lighting changes.

Combining both methods makes results more accurate. Depth images with image processing can help separate mushrooms from the background effectively. Machine learning can then learn accurate mushroom features such as size, shape, and texture to find them more clearly. As camera technology and AI continue to advance, robots equipped with these tools will make mushroom farming faster and more efficient. This means bigger harvests and less manual labor, helping farmers work smarter and achieve better results. For growers and Extension professionals, the key message is that AI can read and understand pictures and convert them into useful information. By using AI in agriculture, a simple image of mushrooms in the soil becomes information about the mushroom count, size, and health, which supports better management, decision-making, and smart farming practices. As these tools advance, they hold strong potential to reduce labor needs and improve harvest efficiency on farms.

Glossary

AI: AI is a part of computer science that focuses on making computers and programs able to do tasks that usually need human thinking. This includes learning, problem solving, and making decisions.

Algorithm: An algorithm is a set of steps a computer follows to solve a problem or complete a task.

Bits: Bits are the smallest units of data in a computer. Each bit can be either 0 or 1.

Bytes: A byte is a group of 8 bits. Computers use bytes to store numbers, letters, or color information in images.

Detection: Detection means finding and identifying objects in an image. It usually shows the location of each object with a box around it.

Edge operators: Edge operators are tools used in image processing to find the borders or outlines of objects in a picture.

Machine learning: Machine learning is a subset of AI where computers learn patterns from data. Instead of being told exactly what to do, the computer improves its performance by learning from examples.

Mask: In computer vision, a mask is a highlighted region of an image that marks which pixels belong to a specific object or area of interest. A segmentation mask shows the exact shape of an object, pixel by pixel, separating it from the background.

Optimization: Optimization is finding the best possible solution to a problem, given a goal and some limits. It means adjusting choices or settings until the result is as good as it can be.

Pixel: A pixel is the smallest part of a digital image. Each pixel holds color information and, when combined with many others, forms the full picture.

Segmentation: Segmentation is the process of dividing an image into parts by marking which pixels belong to each object.

References

Ajith, S., S. Vijayakumar, and N. Elakkiya. 2025. “Yield Prediction, Pest and Disease Diagnosis, Soil Fertility Mapping, Precision Irrigation Scheduling, and Food Quality Assessment Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms.” Discover Food 5(1). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44187-025-00338-1

Ballard, D. H., and C. M. Brown. 1982. Computer Vision (1st edition). Prentice Hall.

Carbonell, J. G., R. S. Michalski, and T. M. Mitchell. 1983. “An Overview of Machine Learning.” In Machine Learning, edited by R. S. Michalski, J. G. Carbonell, and T. M. Mitchell. 3–23. Morgan Kaufmann. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-051054-5.50005-4

Hou, G., H. Chen, M. Jiang, and R. Niu. 2023. “An Overview of the Application of Machine Vision in Recognition and Localization of Fruit and Vegetable Harvesting Robots.” Agriculture 13(9). MDPI. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13091814

Kovasznay, L. S. G., and H. M. Joseph. 1955. “Image Processing.” Proceedings of the IRE 43(5): 560–570. https://doi.org/10.1109/jrproc.1955.278100

Lee, S. 2012. “Depth Camera Image Processing and Applications.” 2012 19th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing: 545–548. https://doi.org/10.1109/icip.2012.6466917

Mane, P., S. Sonone, N. Gaikwad, and J. Ramteke. 2017. “Smart Personal Assistant Using Machine Learning.” 2017 International Conference on Energy, Communication, Data Analytics and Soft Computing (ICECDS): 368–371. https://doi.org/10.1109/icecds.2017.8390128

Tian, H., T. Wang, Y. Liu, X. Qiao, and Y. Li. 2020. “Computer Vision Technology in Agricultural Automation — A Review.” Information Processing in Agriculture 7(1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inpa.2019.09.006