Summary

Florida’s coastal communities face challenges from shoreline erosion, whether from tropical storms, boat wakes, or sea level rise. Structures historically used to protect shorelines include seawalls and bulkheads, which unfortunately create a barrier between the land and water, impact habitat, and can be costly. Increasingly, living shorelines (comprised of plants, oyster reefs, and other structures) are being implemented for shoreline stabilization. This greener solution helps prevent erosion, offers cost savings to homeowners, and supplies multiple ecosystem services to surrounding areas. Living shorelines can be more cost-effective than gray solutions such as seawalls, but implementation requires multiple steps and planning, as outlined in this publication. Many resources are available to simplify the process of planning and installing a living shoreline. Be it permitting, ecosystem services, monitoring, or the impacts of coastal armoring, refer to Resources for more information.

Introduction

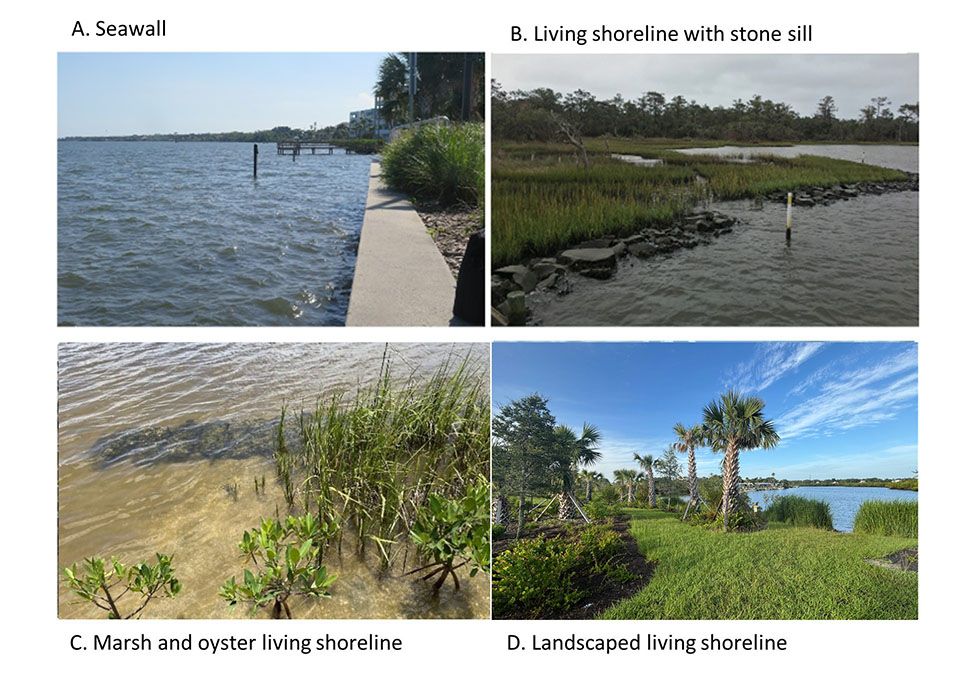

Across Florida, living shorelines are becoming a frequently used management tool for shoreline protection. Coastal armoring, in the form of seawalls, bulkheads, and concrete riprap, creates an unnatural barrier to natural processes and can exacerbate sediment loss. As an alternative, living shorelines are shoreline stabilization methods that use planted vegetation and/or oyster reefs, sometimes in combination with other structures, to protect coastal properties. These components provide natural resistance against weather events by abating wave energy and protecting against erosion. Commonly planted vegetation includes mangroves or smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora; colloquially, “Spartina”) (Figure 1).

Credit: J. Crawford, formerly UF/IFAS

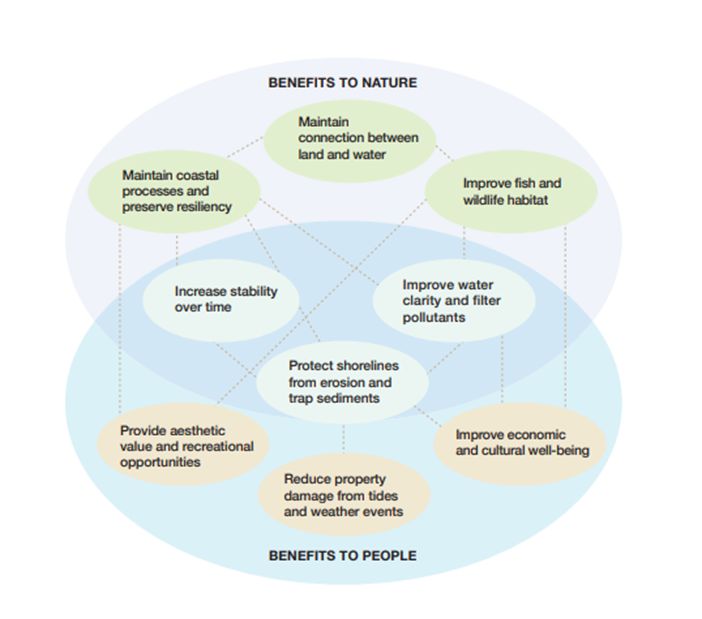

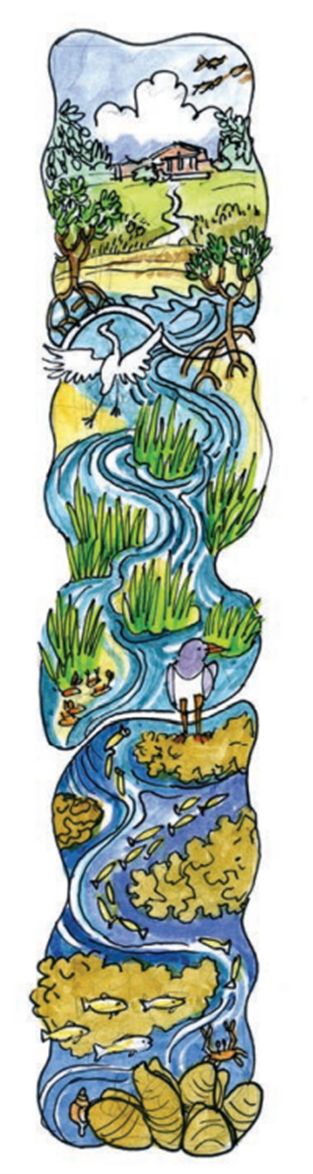

Living shorelines provide benefits to nature and people in a variety of ways (Figure 2). These include improved water quality, habitat, fisheries, uptake of nutrients, and carbon sequestration, all of which hold economic value. Their values will vary depending on habitat type and location, but they can be estimated. For more information on these benefits, see Smyth et al. (2022) and Smyth et al. (2024) on estimating the value of living shoreline benefits.

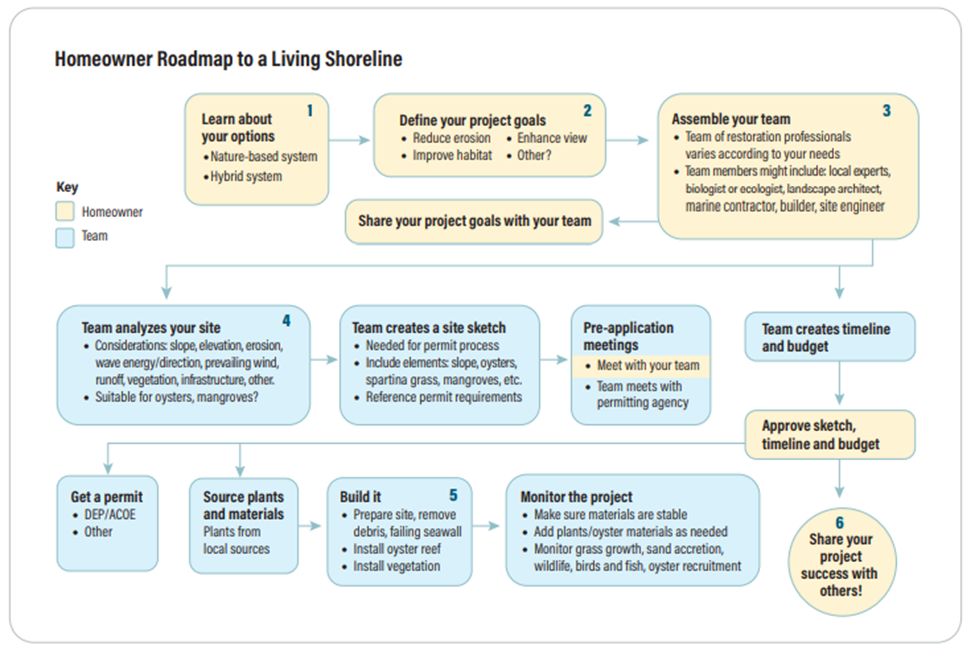

To maximize the benefits of a living shoreline, following a series of steps is necessary to ensure proper placement and effectiveness. Once built, several approaches can be used to ensure the living shoreline persists and reaches project goals. To most effectively plan a living shoreline, knowing when and where to start can be difficult. This publication maps out the broad steps for developing a living shoreline from start to finish, visualized as a roadmap (Figure 3). This roadmap was developed for homeowners and can also serve as a guide for other groups interested in developing living shorelines. The following sections of this publication describe the steps and offer relevant resources.

Credit: Used with permission from Shropshire (2020).

Credit: Used with permission from Shropshire (2020).

Purpose of This Publication

The goal of this publication is to provide a roadmap of UF/IFAS and internet-accessible resources related to living shorelines that will help coastal property owners or natural resource practitioners focused on shoreline management. This information applies to the implementation of living shorelines on both private and managed lands (Figure 3). Other relevant EDIS publications on living shorelines provide guidance on permitting (Barry et al. 2019a, 2019b), describe and quantify ecosystem services provided by living shorelines (Smyth et al. 2022, 2024), and outline methods for monitoring (Reynolds et al. 2021). These publications and more are referenced throughout and listed in the Resources section. Shropshire (2020) provides more detailed information on the steps to a living shoreline.

Step 1: Learn about options.

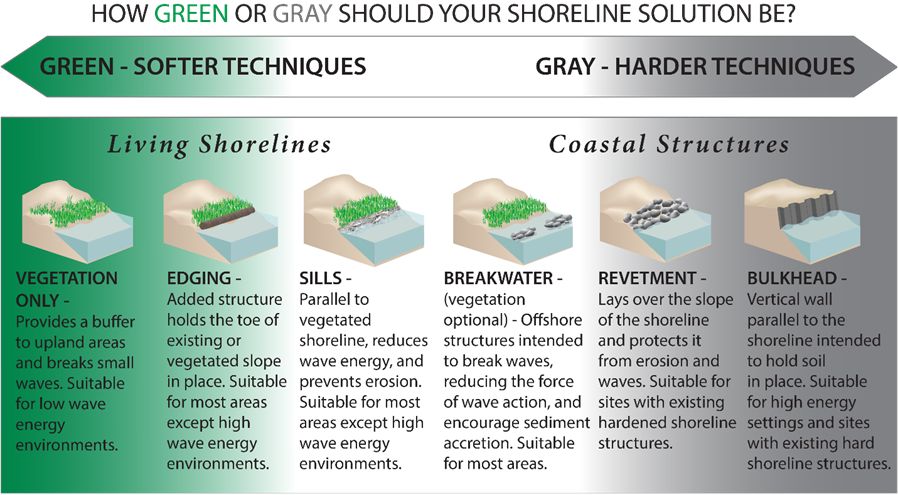

Living shorelines are unique, given the specific conditions at a site. They exist along a spectrum ranging from “green,” which includes more vegetation and “softer techniques,” to “gray,” which includes more structure or “harder techniques” (Figure 4). Before beginning a living shoreline project, environmental factors such as wave climate, water depth, salinity, erosion rates, slope, tidal ranges, proximity to structures, and site conditions will have to be considered. These attributes will be the deciding factors for choosing the proper location and appropriate living shoreline type, and they provide necessary information for obtaining construction permits. If needed, Florida Sea Grant agents, other local Extension specialists, or an experienced environmental consultant or contractor can inspect the area and supply recommendations based on these factors. The type of living shoreline and the project size will both be large factors in the cost.

High or Low Energy?

To begin a living shoreline project, property owners need to determine whether it is a high or low energy site. What does this mean? Breaking waves and currents are the dominant natural forces that cause erosion. The stronger the waves break or the faster the water moves, the higher the energy. Waves and currents can carry materials of varied sizes, from large-grain gravel to smaller-grain sand, silt, and clay. High-energy environments include exposed shorelines along rivers, beaches, areas with high boat traffic, and other offshore environments. Low-energy environments include lakes, swamps, protected marshes, and bayous, bays, or lagoons. These areas will each have a specific combination of vegetation and structure that will work best (Figure 4).

Credit: NOAA (n.d.)

The greenest option, a living shoreline with vegetation only, will be best suited for a low-energy site, where roots can hold soil in place and supply a buffer against small waves. This vegetation-only approach will not be sufficient for high-energy sites with heavy boat traffic or large wind-driven waves because the wave energy will be too stressful for the plants. In high wave energy sites, using additional structures (gray options) may be necessary, or a living shoreline might not be suitable in that location. For models depicting living shoreline suitability, see the Resources section.

Edging, sills, and breakwaters can be incorporated to function as a protective barrier for the planted vegetation. These structures can be adapted easily to fit local needs, as many materials can be used to build sills, reefs, and breakwaters. For example, you can substitute stone sills for oyster shells or use softer techniques where the energy is not quite as high. For examples of what these projects may look like, see Figure 5. For more information on coastal risk reduction offered by these solutions, please see the SAGE Natural and Structural Measures for Shoreline Stabilization guide.

Credit: Smyth et al. (2022): (A) A. Smyth, (B) S. Barry, and (C) C. Reinhardt, UF/IFAS; and (D) A. Roddenberry, FWC.

Costs

Installation and maintenance of living shorelines cost less than fully “gray” shoreline stabilization techniques, such as building bulkheads and seawalls. On average, the materials for a living shoreline are less expensive to install and maintain than most armored shorelines. The average living shoreline project installation will cost between 2%–20% of an armored shoreline per linear foot. When considering the costs of installation, repair, and maintenance together, the average cost of a fully outfitted living shoreline is estimated to be 1%–12% of an armored shoreline per linear foot (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission 2021).

Step 2: Define project goals.

Determine a clear goal for your living shoreline project. If environmental consultants or contractors will be involved, it is helpful to determine goals before meeting to best guide your project. A project may have multiple objectives, such as cost-effective erosion control, reduced erosion and property loss, improvement in surrounding habitat, and storm protection. Identifying the most important goal will help drive decisions about design and materials. The primary goal will also inform what resources are needed and help your team plan for the required permits, timeline, and budget.

Step 3: Assemble a team.

For some projects, you will not need any additional team members besides the property owner to carry out a living shoreline project and facilitate the steps to completion. For more complex projects, a team of professionals can provide support and technical assistance. The Florida Living Shorelines website has helpful text and graphics for the initial resource-gathering process and can help connect those interested in implementing living shorelines with natural resource professionals if needed. This website shares the names of local experts in each region who can provide further information to facilitate your living shoreline and have agreed to be listed publicly on the contacts page. Florida Sea Grant Extension agents for your region can also provide information about efficient local living shoreline practices.

A marine contractor can help design and implement your living shoreline. The Florida Living Shorelines contact page lists marine contractors who have received training and earned educational credits from the Living Shorelines for Marine Contractors course.

Step 4: Team analyzes site and plans living shoreline project implementation.

Permitting

Living shorelines are typically installed below the mean high-water line, which is considered state property. This means that the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP), among other entities such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE, also known as the Corps), regulates the construction and placement of living shorelines via a permitting process. Fortunately, federal and state legislation, such as the Living Shorelines Act (U.S. Congress 2019) and State Bill 1954: Resilient Florida (2021), have made it a little simpler to obtain these permits, demonstrating national and state support for this new practice. For small-scale projects, where the construction takes place no more than 10 feet out beyond the mean high-water line, FDEP offers an exemption that can simplify this process for homeowners as well as guidance from personnel that can facilitate permitting. The request for Verification of Exemption, if approved, will ensure that your project plans satisfy regulatory requirements, helping avoid fines or penalties. This request will also include Submerged Lands Authorization from the FDEP. The approval for exemption can be granted in as little as 30 days. Your FDEP regulatory office (Table 1) will let you know if additional information is needed or if ACOE approval is required, which is common for projects in Florida. For further information on the steps needed to submit these applications, please refer to the guidance in Barry et al. (2019a, 2019b).

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) will review your state permit application if the activities may impact species of concern, such as sea turtles, manatees, or endangered fish. If the construction zone is an area that has nesting birds, horseshoe crabs, or migratory fish, you may need to work outside the breeding or nesting season to avoid any negative impact on these species and their young. The FWC can assist in identifying potential nesting seasons for wildlife species of concern.

Table 1. Contact information for each Florida Department of Environmental Protection district office.

Step 5: Build the living shoreline.

Installation

Installation of living shorelines can take days to weeks (or months for larger, miles-long projects), depending on the size, design, and timeline of your project. When starting the installation, removing debris may be necessary to prepare the site for planting and placing structures. Also consider the ideal planting tide and season. In coastal areas that often experience strong tides and tropical storms, try to plant outside hurricane season, which in Florida is from June 1 through November 30. Similarly, where relevant, fall seasonal high water may be another time to avoid planting. It is best to plant in the spring so that the plants have time to establish before entering their dormancy period over the winter months. During installation, be sure to follow relevant guidelines to protect species of concern that may have been addressed at the permitting phase.

Consider access to the shoreline for construction. A site with land access to bring in materials and equipment will cost less than a project that only has access by water. Typically, installation of any “harder” materials, such as rocks, retaining walls, or oyster reefs, should be completed first, and vegetation should be added last. New plants will require regular watering or irrigation for the first 1–2 months, at minimum. The marine contractor or landscaper on your team can provide technical guidance on the logistics of installation, any required grading or earth work, and appropriate native plants, given the conditions and desired aesthetic at your site.

Maintaining and Monitoring

You may choose to monitor your living shoreline for integrity, performance, or enhancement of ecosystem functions. To manage your living shoreline, you want to ensure that the installed elements are performing the way you intended. Has the living shoreline improved the appearance of your property and increased its value? Are you seeing vegetative growth or an influx of wildlife? Have fishing opportunities improved? Has the size of the beach grown? To estimate the dollar value of the ecosystem services provided by a specific living shoreline, see the Living Shoreline Ecosystem Service Evaluation Tool (Smyth et al. 2024). As with any landscape project, initial replanting may be necessary, especially after storm events and debris removal. Installed plants will take a few years to expand, cover the site, and resemble a natural shoreline.

Comparing measurements from before and after the living shoreline installation can help directly track its impact.

Taking photos of your shoreline project over seasons and years and after storm events is a simple and useful way to track the progress of your project. Pick a set location from which to take photos that demonstrates how your shoreline is changing (for example, a side or cross-sectional view). Photos can be used to document plants and wildlife as well. Having these photos can be an impactful way to demonstrate success to surrounding property owners who are considering a living shoreline approach.

Other simple monitoring components could include keeping a log of bird or fish species encountered as the shoreline grows and settles in. Additionally, mark a PVC or wooden stake with measurements, such as 5 cm increments, and sink it vertically in the sand along the edge of the shoreline. Record the starting level where the sand meets the stake, and then repeatedly record “ground level” over time, perhaps quarterly or annually. Keep a log to see if sand is accumulating on your shoreline. For more resources on methods to measure these shoreline changes, please refer to Reynolds et al. (2021).

Step 6: Share project details.

Sharing details about the successes and challenges of implementing your living shoreline is optional, but it can be a way to give back to others interested in living shorelines so that they can learn from your experience. Speak with your neighbors, friends, and community about your experience regarding the process and outcomes; be sure to share photos of your project that showcase the setting and design (Figure 6). There is a wide variety of resources available to help communicate the details of a living shoreline project. See Resources for more information, although this list is by no means exhaustive. It may help to reach out and research locally.

Credit: A. Roddenberry, FWC

Glossary

coastal armoring: A manufactured structure designed to either prevent erosion of the upland property or protect eligible structures from the effects of coastal waves and current action.

ecosystem: A community of interacting organisms plus the physical environment in which they live.

ecosystem services: The benefits that ecosystems provide to human societies, such as resources and a livable environment.

erosion: A geological process by which the earth is worn away.

habitat: The space, resources, and conditions a species requires to complete its life cycle.

living shoreline: A management approach that uses natural materials, such as oyster reefs, mangroves, and marsh grasses, to stabilize coastal edges, prevent erosion, and maintain natural coastal processes while protecting property.

mean high-water line (MHWL): The line that represents the average location of high tide along a shoreline (the average of all the high-water heights observed over the period as defined by the National Tidal Datum Epoch).

nutrients: Chemicals that an organism needs for survival (e.g., carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus).

shoreline stabilization: The use of engineered structures, vegetation, or land management practices to provide protection of the shoreline from future or existing erosion.

Credit: Used with permission from Shropshire (2020).

Resources

Other Relevant EDIS

SL481, “Living Shoreline Monitoring—How do I evaluate the environmental benefits of my living shoreline?”

Getting Started

Florida Living Shorelines website

NOAA, [PDF] Guidance for Considering the Use of Living Shorelines

Restore America’s Estuaries, “What are living shorelines?”

SAGE, [PDF] Natural and Structural Measures for Shoreline Stabilization

More Detailed Information

Center for Coastal Resources Management, Information on living shorelines and decision tools

Living Shorelines Academy, https://sites.google.com/view/ccclivingshorelineacademy/academy

Living Shorelines for Florida: A Practical Guide for Building Coastal Resilience (2025) by S. Barry, V. Encomio, M. Shropshire, and G. Stibolt

Restore Your Coast, Coastal Restoration Toolkit, Coastal Erosion Funding

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Systems Approach to Geomorphic Engineering

Exploring the Impact of Living Shorelines

ArcGIS, Living Shoreline Suitability Models: Mosquito Lagoon and Northern Indian River Lagoon

FIU, Living Shoreline Site Assessment Tool: Indian River Lagoon

FWC, Story map by Christopher Boland, “Suitable Sites for Living Shorelines in Tampa Bay”

National Wildlife Federation (NWF), Softening Our Shorelines report

NOAA Habitat Blueprint

NOAA Fisheries, Living Shorelines story map

NOAA Fisheries, Restoration Atlas

PBS News, John Upton on “As seas rise, Americans use nature to fight worsening erosion”

WJCT News, Melissa Ross on “Living shorelines are being created along Florida's coast”

Suitability for Living Shorelines

ArcGIS Story Maps, A Living Shorelines Suitability Model for Perdido and Pensacola Bay, Florida. An Alternative Method for Shoreline Erosion

References

Barry, S. C., S. Martin, and E. Sparks. 2019a. “A Homeowner’s Guide to the Living Shoreline Permit Exemption Part 1: Florida Department of Environmental Protection: SG187, 2/2019.” EDIS 2019 (1). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-sg187-2019

Barry, S. C., S. Martin, and E. Sparks. 2019b. “A Homeowner’s Guide to the Living Shoreline Permit Exemption Part 2: United States Army Corps of Engineers: SG189, 3/2019.” EDIS 2019 (2). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-sg189-2019

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. 2021. Living Shorelines Training for Marine Contractors.

Florida Senate. 2021. “SB 1954: Statewide Flooding and Sea Level Rise Resilience.” Last action May 13, 2021. https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2021/1954

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). n.d. “Living Shorelines.” NOAA Habitat Blueprint. Accessed on August 15, 2023. https://www.habitatblueprint.noaa.gov/living-shorelines/

Reynolds, L., N. C. Stephens, S. C. Barry, and A. R. Smyth. 2021. “Living Shoreline Monitoring—How do I evaluate the environmental benefits of my living shoreline? SS694/SL481, 1/2021.” EDIS 2021 (1). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ss694-2021

Shropshire, M. M. 2020. “WeShore: Connecting Homeowners, Contractors, and Nature Through Living Shorelines.” Master’s thesis, University of Florida. https://original-ufdc.uflib.ufl.edu/AA00086387/00001

Smyth, A. R., L. K. Reynolds, S. C. Barry, N. C. Stephens, J. T. Patterson, and E. V. Camp. 2022. “Ecosystem Services of Living Shorelines: SL494/SS707, 5/2022.” EDIS 2022 (3). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ss707-2022

Smyth, A. R., L. K. Reynolds, S. C. Barry, N. C. Stephens, J. T. Patterson, and E. V. Camp. 2024. “Living Shoreline Ecosystem Service Valuation Tool: SL516, 5/8/2024.” EDIS 2024 (3). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-SS729-2024

U.S. Congress. House. 2019. "H.R.3115: Living Shorelines Act of 2019." 116th Congress, 1st session, H. Rept. 116-316. Last modified November 26, 2019, at https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/3115