Introduction

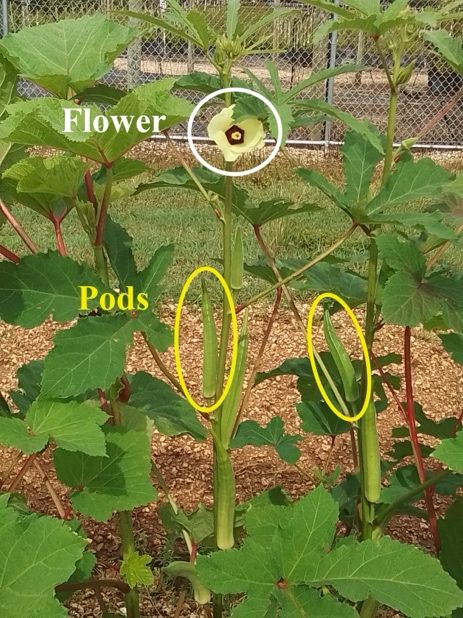

Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench) (Figure 1) is a versatile crop that has gained global popularity due to its nutritional and medicinal values, as well as increasing consumer interest in healthy foods (Elkhalifa et al. 2021). As a member of the mallow family, Malvaceae, which includes cotton and hibiscus, okra is generally self-pollinating and known endearingly as lady’s fingers (Kumar 2019). In south Florida, okra can grow year-round, making it an excellent option for local farmers seeking multi-season production.

Credit: Xingbo Wu, UF/IFAS

Okra is believed to have originated in Africa and has been cultivated for centuries in Africa, Asia, and the Americas (Singh et al. 2014). It is a warm-season crop that is sensitive to frost but can tolerate drought, making it mainly cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions (Westerfield 2022). As of 2023, the global production of okra was 12,709,392 tons (11,523,291.5 tonnes), with India being the largest producer at 62%, followed by Nigeria at 16%, and Mali at 6.6%, while the United States represented 0.09 % (FAO 2023).

In the United States, the total amount of okra harvested in 2022 was 4,378 acres (1,771.71 hectares), with Florida contributing 155 acres (62.7 hectares) (USDA NASS 2022). Many states, including Texas, Georgia, California, Oklahoma, Alabama, and Florida, produce okra (USDA NASS 2022). Yields of the crop range from less than 600 to more than 1,000 bushels/acre (20.2–33.6 metric tons per hectare) (Li et al. 2021).

Despite the growing domestic okra production acreage, a significant amount of okra consumed in the United States is still imported, with import values reaching $60.8 million in 2023 (USDA ERS 2023). This expanding domestic market, especially the demand for fresh and high-quality okra, has raised interest among growers in cultivating this high-value crop more effectively using the right varieties and optimal cultural practices. This publication offers south Florida growers and consumers key insights into okra’s nutrient content, its health benefits, and guidelines for growing and harvesting the crop.

Nutritional Value

Okra is a nutritious vegetable with medicinal benefits, making it an excellent addition to a balanced diet (Table 1). One of its standout features is its high fiber content, with a raw 100-gram (~3.5-ounce) serving providing 11% of the recommended daily intake (USDA ARS 2018b). Fiber, particularly soluble fibers such as pectic polysaccharides, supports digestive health and nourishes the gut microbiome by acting as a prebiotic, feeding beneficial gut bacteria (Wu et al. 2021; Makki et al. 2018). These microbes ferment fiber, producing short-chain fatty acids like acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which help strengthen the intestinal barrier, reduce inflammation, and promote overall gut health.

Beyond fiber, okra is rich in essential vitamins and minerals that boost immunity (e.g., vitamins C and A), support muscle function (e.g., magnesium and potassium), and enhance bone strength (e.g., calcium and vitamin K). With its low fat and sugar content, okra is a healthy food that fits well into weight management diets (Table 1). However, okra is most often cooked before consumption (boiled and drained), generating losses of nutrient output at or exceeding half of the raw value (USDA ARS 2018a).

Table 1. Nutritional composition of okra per 100 g (~3.5 oz) per serving. Data cells in boldface indicate losses of nutrient output in cooked okra, at or exceeding half the raw value.

Medicinal Attributes

Okra’s medicinal value comes from its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, hypoglycemic, and hypolipidemic properties (Table 2). The antioxidants in okra, such as polyphenols, are rich in the pod and help combat oxidative stress, which is linked to aging, inflammation, and chronic diseases.

A unique feature of okra is its mucilage, a natural gel-like substance made of polysaccharides, including pectin and soluble fibers, that gives okra its characteristic “slimy” texture when cooked. Mucilage slows the digestion and absorption of carbohydrates, leading to a gradual release of glucose into the bloodstream. This helps regulate blood sugar levels, making okra particularly beneficial for individuals with diabetes or those at risk of developing it (Elkhalifa et al. 2021; Agregán et al. 2023). Additionally, the soluble fibers in mucilage bind to bile acids and cholesterol in the digestive system, helping to excrete them, thus reducing the risk of cardiovascular diseases by lowering LDL (“bad”) cholesterol levels in the body.

Versatility

Okra is valued for its edible pods used in various dishes. They can be prepared in several ways, including grilled, boiled, or added to soup, often alongside meat. Fried okra pods are key ingredients in popular dishes from Mexico, Spain, Africa, and South China. Okra can also be eaten in salads, where blanched or lightly cooked pods add a unique texture. Beyond fresh consumption, okra is processed into canned, dehydrated, and frozen products, making it a highly versatile crop with many culinary uses.

In addition to its pods, okra is a multi-use crop valued in various countries for its seeds and by-products. In India, Turkey, and parts of West Africa, okra seeds are roasted and used as a coffee substitute due to their unique flavor and caffeine-free nature (West 2020). Okra seeds are also marketed as a source of high-quality oil. Compared with walnut oil and peanut oil, okra seed oil contains relatively high total phenols (959.7 μg/mL), fat-soluble vitamins (0.002 μg/100 mL of vitamin A and 1.4 μg/100 mL of vitamin D), and a variety of essential mineral nutrients, which support vision and bone health and reduce blood clotting (Guo et al. 2024). Moreover, the plant’s residuals, rich in crude fiber, are utilized in industries such as paper manufacturing (Hemeyer 2010).

Table 2. Health benefits of various phytochemicals present in okra pods and seeds.

Source: Adapted from content in Elkhalifa et al. (2021) and Samtiya et al. (2021).

Okra Production Practices

Varieties

Okra has several varieties that differ in pod color and shape, offering diversity for both culinary and agricultural purposes (Table 3). The most common type is green okra, with smooth or slightly ribbed pods. It is widely used in cuisines around the world and is the primary type grown in Florida. Red okra, such as the ‘Burgundy’ variety, holds ornamental value with its striking red pods (although turning green when cooked), adding a distinctive visual appeal to both gardens and salads.

Okra pods also vary in size, ranging from small, tender pods ideal for pickling to longer, thicker pods preferred for making stew or fried okra. Some heirloom varieties, such as ‘Clemson Spineless’, the most widely grown variety in Florida, are prized for their tenderness and ease of harvesting due to their minimal spines (small hair-like structures on pods and branches). Okra spines can irritate skin, so the smooth surface of this cultivar makes it easier to harvest and handle.

Aside from those mentioned in Table 3, not all varieties are suited for south Florida environmental conditions; therefore, it is important to consult seed vendors before planting to ensure the intended land meets the cultivars’ growing requirements. For information on recommended varieties for south Florida, refer to chapter 10 in the most recent edition of the Vegetable Production Handbook of Florida.

Table 3. Recommended okra varieties for Florida growers.

Land Preparation and Planting

Prior to planting, ensure the soil is well-drained. Tillage is necessary to improve soil structure in the gravelly and marl soils of south Florida, ensuring proper root penetration. Okra is typically direct-seeded using a precision planter to ensure uniform spacing and emergence. Soil temperatures in the range of 25°C–35°C are required for good germination, with accelerated growth being observed at 35°C (Uwiringiyimana et al. 2024). Failure in seed germination is possible at temperatures below 17°C, while temperatures above 42°C cause flower buds to dry out, resulting in yield reduction (Uwiringiyimana et al. 2024). Okra seedlings typically emerge within 5–10 days after planting under warm conditions. In south Florida, growers often plant okra after a winter vegetable crop, allowing for harvests from early spring through late fall. Alternatively, okra can grow exclusively in the summer, which serves as the off-season for many other vegetables (e.g., tomatoes and beans).

Sow okra seeds at a depth of 0.5–1 inch (1.3–2.5 cm), with plant spacing that ranges from 4–10 inches (10.2–25.4 cm) within the row (Seal et al. 2024). The variation in spacing depends on the okra variety and desired plant density. Smaller okra varieties benefit from closer spacing, as it maximizes yield per area and helps suppress weeds by creating a dense canopy. Larger okra varieties, which have a more extensive branching habit, require wider spacing to allow for proper growth, air circulation, and reduced competition between plants. Space rows 36 inches (91.4 cm) apart for optimal growth and ease of cultivation (Li et al. 2021).

Fertilization

Standard soil fertility tests (including pH, P, K, Ca, Mg, S, B, Cu, Mn, Zn, and fertilizer recommendations) and plant tissue analysis can be requested from the UF/IFAS Extension Soil Testing Laboratory. See EDIS publications SL135 and SL131 to download the Producer Soil Test Form and Plant Tissue Test Form, respectively. For information on soil testing and plant tissue analysis, see in the most recent edition of the Vegetable Production Handbook of Florida.

Okra requires moderate amounts of nutrients. UF/IFAS recommends applying 120 lb/acre (134.5 kg/ha) of N. Apply 120–150 lb/acre (134.5-168.1 kg/ha) each of phosphorus (P₂O₅) and potassium (K₂O) for soils with low Mehlich-3 soil test P and K values. For soils with medium Mehlich-3 soil test P and K values, apply 100 lb/acre (112.1 kg/ha) of both P₂O₅ and K₂O. Before planting, apply about 30–40 lb/acre (33.6–44.8 kg/ha) of N and 40–60 lb/acre (44.8–67.7 kg/ha) each of P₂O₅ and K₂O based on your soil test results. Side dress the remainder of the fertilizers in two or three applications, starting three to four weeks after planting, to support the crop’s ongoing nutrient needs. It is important not to overapply N, which can cause extensive leafy growth and reduce the number of pods.

Organic growers can use compost, manure, or organic fertilizers (e.g., bone meal, blood meal, or fish emulsion). These soil amendments should be well-aged or composted to meet food safety requirements and to avoid problems with nutrient availability. If plants begin to show signs of nutrient deficiency, use foliar sprays to boost the uptake of nitrogen or other nutrients. For more detailed advice, refer to chapter 2 of the most recent edition of the Vegetable Production Handbook of Florida.

Irrigation

Okra requires up to 1.5 inches (3.8 cm) of water per week or per 10 days, either from rainfall or irrigation, depending on the growth stage and soil type (Westerfield 2022). Irrigation scheduling should account for the crop’s growth stage, soil characteristics, and weather conditions. In marl soils, apply irrigation less frequently but with longer durations to prevent waterlogging and ensure deep water infiltration, as these soils retain moisture well. In contrast, gravelly soils require frequent but light irrigation to maintain consistent moisture levels since they have low water retention and quick drainage. Young okra seedlings benefit from frequent but light watering to establish their roots, while mature plants require less frequent but deeper irrigation to promote healthy growth and pod development. Irrigation methods such as water guns, center pivots, or sprinklers are commonly used on flat fields.

Credit: Cat Wofford, UF/IFAS

Pest and Disease Management

Major insect pests of okra include aphids, thrips, and leaf beetles, which can significantly reduce yield and marketability. Recently detected in south Florida, the two-spot cotton leafhopper can reduce okra yield by over 50% (Liburd et al. 2024; Devi et al. 2018). These pests can migrate from okra fields to other crops, such as tomatoes, beans, eggplants, and ornamentals. Silverleaf whitefly can also multiply prolifically on okra, although the plant compensates for the feeding damage (Li et al. 2021). However, okra is a potential off-season breeding host for all these aforementioned insect pests. At the beginning of a vegetable season, they move to the newly planted host crops.

Several diseases also pose significant threats to okra, including powdery mildew, Cercospora leaf blight, and charcoal rot. Okra producers in south Florida have reported issues with root rot and seedling damping-off caused by Rhizoctonia and Fusarium. More information on managing these diseases is available in the EDIS publication HS1514, “The Control Strategies for Seed-Borne Diseases on Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus),” and in chapter 10 of the most recent edition of the Vegetable Production Handbook of Florida.

Okra is notoriously susceptible to nematodes. Avoid planting in fields with severe nematode infestations. Rotation with crops like corn and cover crops such as sorghum-sudan grass and sunn hemp is recommended to mitigate nematode populations. Field observations in south Florida have indicated that rotating okra with green beans significantly reduces nematode populations, particularly root-knot nematodes, compared to soils where okra followed cucumber in the previous season. Refer to EDIS publication ENY-043, “Nematode Management in Okra,” for more information.

Harvest

Okra is handpicked at the immature stage and sold for local consumption, although it is primarily sold for shipment to other states and even other countries. Okra plants mature rapidly. Therefore, harvest the pods every two to three days, when they are 2–3 inches (5.1–7.6 cm) long and still tender, to prevent them from becoming overmature and fibrous (Westerfield 2022; Perkins-Veazie 2016). As previously mentioned, okra plants have tiny spines that can irritate the skin; therefore, workers often wear gloves and long sleeves to protect themselves during harvest.

References

Agregán, R., M. Pateiro, B. Bohrer, et al. 2023. “Biological Activity and Development of Functional Foods Fortified with Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus).” In Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 63 (23): 6018–6033. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2022.2026874

Devi, Y. K., S. Pal, and D. Seram. 2018. “Okra Jassid, Amrasca biguttula biguttula (Ishida) (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) Biology, Ecology and Management in Okra Cultivation.” Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research 5 (10): 332–343.

Elkhalifa, A. E. O., E. Alshammari, M. Adnan, et al. 2021. “Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) as a Potential Dietary Medicine with Nutraceutical Importance for Sustainable Health Applications.” Molecules 26 (3): 696. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26030696

Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). 2023. Data for okra, over worldwide and total area for 2023, presented as an aggregated sum. FAOSTAT Statistical Database. Retrieved May 2025, from https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL/visualize

Food and Drug Administration. 2016. “21 CFR Part 1010: Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels.” Accessed May 2025. https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2016-11867.pdf

Guo, G., W. Xu, H. Zhang, et al. 2024. “Characteristics and Antioxidant Activities of Seed Oil from Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.).” Food Science & Nutrition 12 (4): 2393–2407. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.3924

Hemeyer, E. 2010. “Okra Papermaking.” In Flesh We Build, October 15. https://infleshwebuild.blogspot.com/2010/10/okra-papermaking.html

Kumar, S. 2019. “Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus): A Review on Its Cultivation, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacology.” Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 8 (3): 1734–1742.

Li, Y., W. Klassen, M. Lamberts, T. Olczyk, and G. Liu. 2021. “Okra Production in Miami-Dade County, Florida.” HS-857. University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/TR009

Liburd, O. E., S. E. Halbert, N. Samuel, and A. J. Dreves. 2024. “Two-Spot Cotton Leafhopper, Hemiptera: Cicadellidae, Typhlocybinae, Empoascini; Amrasca biguttula (Ishida)—A Serious Pest of Cotton, Okra and Eggplant that Has Become Established in the Caribbean Basin.” FDACS-P-02229. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Division of Plant Industry. https://ccmedia.fdacs.gov/content/download/117692/file/two-spot-cotton-leaf-hopper-pest-alert.pdf

Makki, K., E. C. Deehan, J. Walter, and F. Bäckhed. 2018. “The Impact of Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota in Host Health and Disease.” Cell Host & Microbe 23 (6): 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.012

Perkins-Veazie, P. 2016. “Okra.” In The Commercial Storage of Fruits, Vegetables, and Florist & Nursery Stocks, edited by K. Gross, C. Y. Wang, and M. Saltveit. Agriculture Handbook 66. U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service.

Samtiya, M., R. E. Aluko, T. Dhewa, and J. M. Moreno-Rojas. 2021. “Potential Health Benefits of Plant Food-Derived Bioactive Components: An Overview.” Foods 10 (4): 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040839

Seal, D. R., Q. Wang, R. Kanissery, et al. (2023) 2024. “Chapter 10. Minor Vegetable Crop Production: VPH ch. 10, CV294, rev. 6/2024.” EDIS (VPH). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-cv294-2023

Singh, P., V. Chauhan, B. K. Tiwari, et al. 2014. “An Overview on Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) and Its Importance as a Nutritive Vegetable in the World.” International Journal of Pharmacy and Biological Sciences 4 (2): 227–233.

USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS). 2018a. “Okra, Cooked, Boiled, Drained, Without Salt.” FoodData Central. Accessed May 2025. https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/food-details/169261/nutrients

USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS). 2018b. “Okra, Raw.” FoodData Central. Accessed May 2025. https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/food-details/169260/nutrients

USDA Economic Research Service (ERS). 2023. Data from “Vegetables and Pulses Data—Trade and Prices by Category and Commodity.” Accessed May 2025. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/vegetables-and-pulses-data/trade-and-prices-by-category-and-commodity

USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). 2024. “California: State and County Data.” 2022 Census of Agriculture. Vol. 1, Ch. 1. Accessed May 2025. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2022/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_1_State_Level/California/

Uwiringiyimana, T., S. Habimana, M. G. Umuhozariho, et al. 2024. “Review on Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench) Production, Nutrition and Health Benefits.” Rwanda Journal of Agricultural Sciences 3 (1): 71–87.

West, C. 2020. “Roasted Okra Seed Coffee.” Sweet Miscellany, September 30. https://www.sweetmiscellany.com/okra-seed-coffee/

Westerfield, R. 2022. “Home Garden Okra.” C 941. University of Georgia Extension. Accessed May 2025. https://site.extension.uga.edu/colquittag/files/2023/10/Okra.pdf

Wu, D. T., X. R. Nie, R. Y. Gan, et al. 2021. “In Vitro Digestion and Fecal Fermentation Behaviors of a Pectic Polysaccharide from Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) and Its Impacts on Human Gut Microbiota.” Food Hydrocolloids 114: 106577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106577