Introduction

The Up in the Air, Down in the Water program is a combined research and education effort of the Urban Water Cycle Lab at the UF/IFAS Gulf Coast Research and Education Center in Hillsborough County, Florida. This publication addresses nitrogen (N) in atmospheric deposition that falls within the Tampa Bay watershed. Atmospheric deposition is the process whereby precipitation (rainfall), dust, and particles in the air move from the atmosphere to Earth’s surface. Many different substances can be introduced to Earth’s surface via atmospheric deposition, including N, which is one of the nutrients responsible for the occurrence and proliferation of harmful algal blooms in waters such as Tampa Bay (Muni‑Morgan et al. 2024) as well as in other parts of the world. The project’s focus is the connection between air quality and water quality, with the understanding that N in atmospheric deposition is a major source of excess N that can cause water quality degradation such as algal blooms in our water resources. Harmful algal blooms cause fish kills, death of marine mammals, and loss of tourism and recreation opportunities for our beaches, and can even impact human health through certain toxins that some algae release to the environment.

The purpose of this fact sheet is to explain where the N in atmospheric deposition comes from, how it moves to Earth’s surface, how it can affect water quality, and how we can better manage atmospherically derived N in our watersheds. This publication is intended for residents and decision-makers. It contains information useful to anyone who is concerned about air and water quality and the connections between the two.

What is atmospheric deposition?

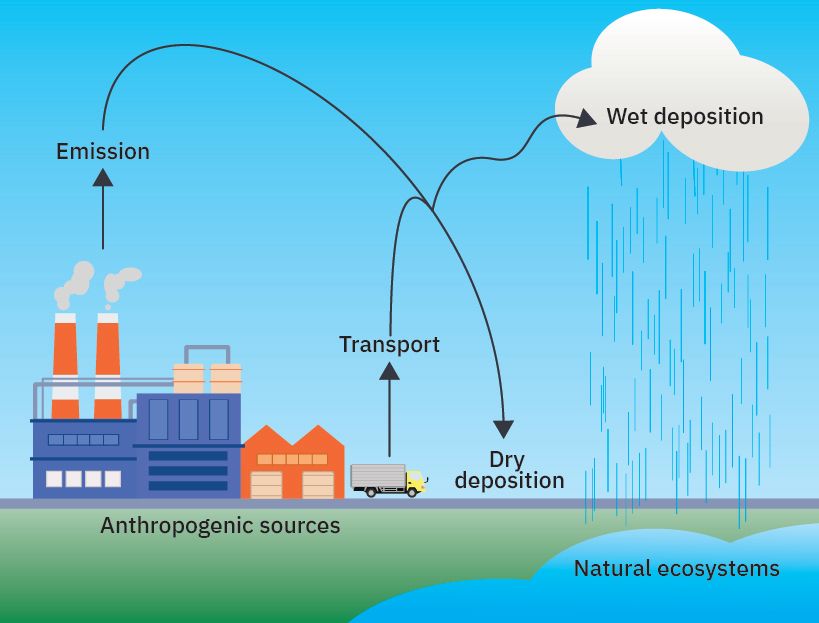

Atmospheric deposition can be associated with gases, particles, or dusts in the atmosphere and may contain many potential chemical elements, including but not limited to N, dissolved metals, sulfur, and calcium. Atmospheric deposition is divided into two components: wet deposition, which occurs when these chemical elements are deposited on the Earth through rain or snowfall; and dry deposition, which occurs when the elements settle as particles or dust onto surfaces such as streets, rooftops, and the tree canopy (Figure 1). You can learn more about N sources in urban landscapes at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/SS479 (Reisinger et al. 2020).

Credit: UF/IFAS Communications

Atmospheric deposition (both wet and dry) has long been known as a source of chemical enrichment of surface waters on Earth (Yang and Lusk 2018). For example, the Chesapeake Bay watershed in the northeastern U.S. gets almost one-third of its annual N load from atmospheric deposition. Similarly, Tampa Bay in Florida gets more than half of its annual N load from atmospheric deposition, either directly to the bay’s surface or indirectly to the bay through stormwater runoff (i.e., rainfall that becomes runoff and flows to the bay) (Poor et al. 2001; Poor et al. 2006; Strayer et al. 2007).

The chemical elements in atmospheric deposition can originate from natural or human-caused sources. Wildfires, animal manures, and lightning are all natural sources or processes that contribute chemical elements to atmospheric deposition. For example, animal manures can contribute N in the form of ammonia (NH3) to the atmosphere. The rapid heating and cooling produced by lightning can facilitate chemical reactions in the atmosphere that produce nitrogen dioxide, which is then dissolved in precipitation and enriches rainfall with N. Human-caused sources include fossil fuel burning at power plants or from vehicle emissions, as both of these processes give off combustion products, dust, and chemicals to the air. In many urban areas, the natural sources of atmospheric deposition are minimal, and fossil fuels and vehicle emissions become the most important atmospheric deposition sources instead.

How does nitrogen become a part of atmospheric deposition over cities?

For cities, N in atmospheric deposition is primarily associated with fossil fuel burning at power plants and factories and from vehicle emissions (Figure 1). In the Tampa Bay urban area, most atmospheric N is in the form of nitrogen oxides (NOx). Work by the Tampa Bay Estuary Program has shown that nitrogen oxide emissions from vehicles are nearly four times higher than those from power plants in the Tampa Bay watershed. It is likely that nitrogen oxides from vehicles do not go as high up in the atmosphere compared to those from the tall emission stacks of power plants, and that is likely why vehicles play a much larger role in local atmospheric N deposition for Tampa Bay (Figure 2). Even so, the nitrogen oxides that come from any source can become part of the air over our cities and eventually come back down in dust or rainfall. This is where the Up in the Air, Down in the Water program gets its name — from the idea that what goes up in our air (vehicle emissions with nitrogen oxides) eventually comes back down to our water (the Tampa Bay).

Credit: UF/IFAS Communications

Why are we concerned about N in atmospheric deposition?

Nitrogen in atmospheric deposition is important because algal production within the Tampa Bay and other waters state- and worldwide is N-limited, which means that N is the nutrient that algal growth responds to most when nutrients are added to a water body (Figure 3).

Credit: UF/IFAS Communications

The Bay Region Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment (BRACE) indicated in 2013 that 57% of all N that enters Tampa Bay originates from atmospheric N (17% as direct deposition to bay waters, and 40% as deposition to the watershed that is then incorporated into stormwater and channeled to the bay via runoff after it rains). This finding underscores the need for actionable data on the sources, pathways, and impacts of atmospheric N for Tampa Bay’s estuarine and coastal waters (Poor et al. 2013). The Up in the Air, Down in the Water program is aimed at better understanding the contribution of atmospheric deposition to N loads in stormwater and the potential impact of atmospherically derived N on water quality in the Tampa Bay watershed and beyond. Below are a few recent University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) research results related to atmospheric deposition of N and impacts on Florida’s waters.

- Rainfall collected in urban areas of Pinellas County, FL (part of the Tampa Bay watershed), contained a pool of nitrogen that was readily used by both Karenia brevis (Florida red tide) and Pyrodinium bahamense, two common algal species in the Tampa Bay region (Muni‑Morgan et al. 2024).

- Another study in Pinellas County showed that annual total N wet deposition to the county was 1.3 tons/year (Muni-Morgan et al. 2024).

- Rainfall samples from Hillsborough County, FL (also part of the Tampa Bay watershed), contributed 0.4 kg N/hectare (0.4 lb/acre) to the ground surface (Lusk et al. 2023).

- Atmospheric deposition was the source of 35% of nitrate-nitrogen in stormwater runoff collected from multiple storms across the Tampa Bay region. Furthermore, atmospheric deposition was the leading source of nitrate-nitrogen in the samples, even more prevalent than turfgrass fertilizers, soils, manures, and other urban sources of nutrients (Jani et al. 2020).

- Runoff samples from urban lawns in the Indian River Lagoon watershed of Florida showed that 15% to 30% of nitrate-nitrogen was derived from atmospheric deposition (Krimsky et al. 2021).

What are some management actions that communities can take to better manage atmospheric nitrogen?

The Tampa Bay Estuary Program (TBEP), a federal-local partnership dedicated to overseeing the health and well-being of Tampa Bay, has outlined several actions for communities to better manage atmospheric N deposition, which are listed below.

- Reduce N emissions by encouraging power plant upgrades and encouraging people to use alternative sources of energy instead of solely relying on fossil fuels. This includes expanding our use of solar energy in the Tampa area.

- Support efforts at regional and national levels to reduce vehicle emissions. This includes activities such as requiring more fuel-efficient vehicles, carpooling, using bicycles, using electric vehicles, expanding public transportation options, and telecommuting.

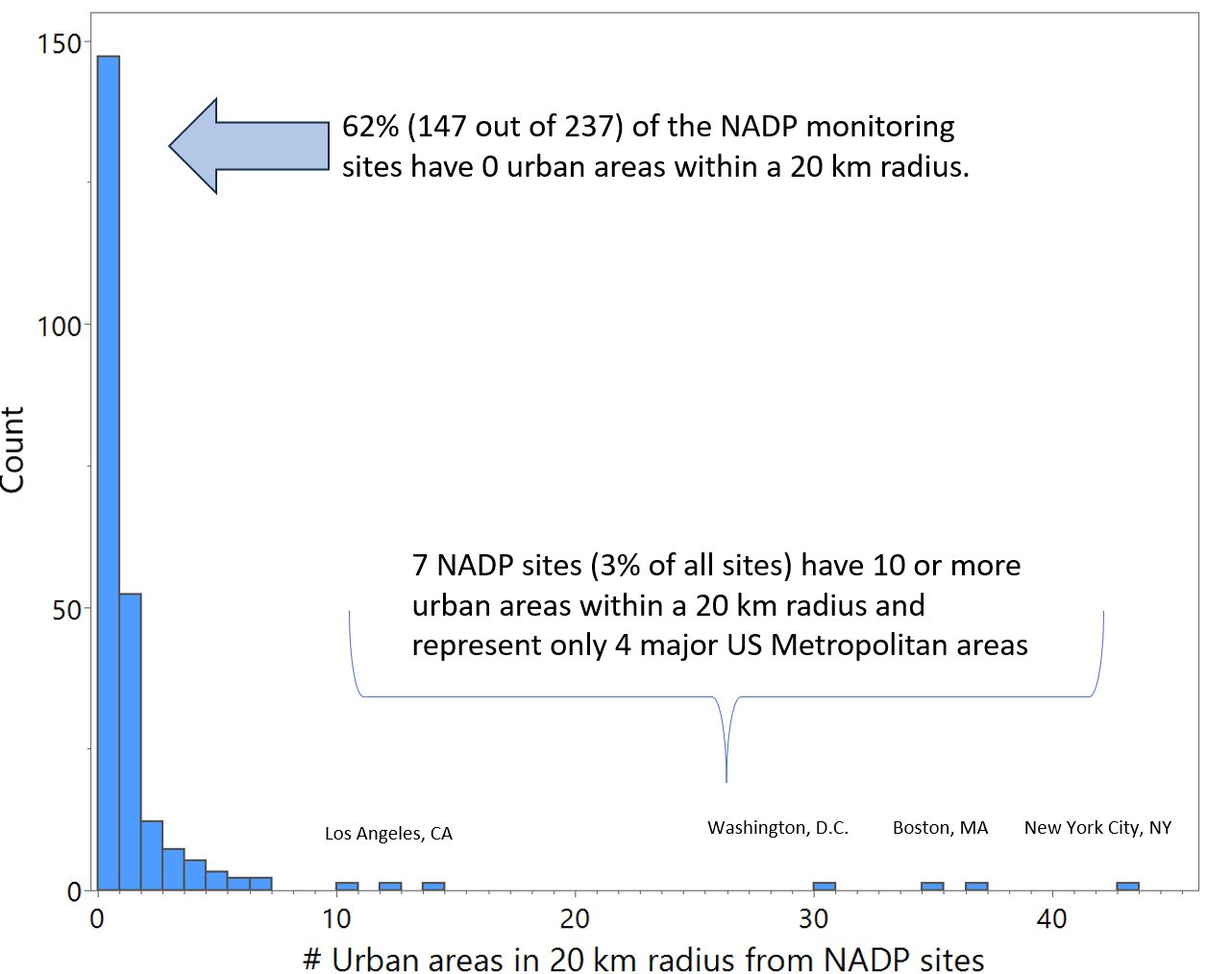

- Support and expand air quality monitoring efforts in Tampa Bay. On the premise that we cannot improve what we do not measure, we need to have more complete data on the amount of N in local atmospheric deposition and research on how much of it makes its way to our waters. The National Atmospheric Deposition Program (NADP) has a network of over 100 atmospheric N monitoring stations nationwide, but very few of them are located near urban areas. For example, a survey of NADP monitoring sites by our lab found that 62% (147 out of 237) of NADP monitoring sites have zero urban areas within a 20 km radius, indicating that most NADP sites are capturing data representative of non-urban areas. Conversely, only seven NADP sites (3% of all sites) have 10 or more urban areas within a 20 km radius and represent only four major U.S. metropolitan areas (Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., Boston, and New York City), meaning that the other major U.S. metropolitan areas, including Tampa Bay, do not have an urban monitoring station for atmospheric N deposition (Figure 4).

An atmospheric N monitoring station in the urban area of Tampa Bay’s watershed should be a major goal. This is because vehicle emissions play such a large role in local N deposition, and if we are only monitoring outside of the urban area, we are likely missing the impact of concentrated vehicle usage in the city. The nearest NADP monitoring site to Tampa Bay is the Verna Wellfield site in Sarasota County. This site is 24.7 km (17 miles) east of the coast and is designated as rural land use; thus, it is likely that we are missing a large portion of local atmospheric N in our monitoring efforts.

Credit: T. Charan and M. Lusk, UF/IFAS

What are some actions that individuals can take to better manage atmospheric nitrogen deposition?

Because most atmospheric N deposition in Tampa Bay comes from vehicle and power plant emissions, it follows that reducing vehicle emissions and dependence on fossil fuels is the primary action that individuals can take to reduce N loads from the atmosphere to the water. We can encourage our community leaders to adopt practices that enable more public transportation options, renewable energy sources such as solar power, and power plant upgrades that reduce N emissions in the first place. We can also do as much as we can to reduce our vehicle use by cutting down on unnecessary trips, combining trips when possible, using public transport or bicycles, and considering electric vehicles.

Additionally, because atmospheric N often enters our watershed by rainfall, we can implement actions that capture more rainfall and prevent it from becoming runoff. Runoff from our lawns and neighborhoods often makes its way to the bay eventually; therefore, stopping that pathway can be one way to reduce N transport to bay waters. Consider diverting roof runoff to vegetation instead of sidewalks or driveways, so the runoff is soaked up by soil and plants rather than channeled to runoff flows.

Conclusions

Research from UF/IFAS demonstrates that atmospheric deposition is a major source of N (and potentially other nutrients) to surface waters in Florida, including those in the Tampa Bay area. This N often originates in our urban watersheds as emissions from power plants and vehicles, interacts with water in the air, and then returns to the ground surface through rainfall. In rainfall and stormwater runoff, this N can then fuel harmful algal growth in our water bodies. Decision-makers and residents in the state can support regional and national efforts to upgrade power plants, reduce reliance on motor vehicles for transportation, capture rainfall in permeable surfaces such as rain gardens, and consider changes to renewable energy sources. We also need to implement local urban monitoring of atmospheric N deposition so we can more fully understand the extent of local urban sources’ contributions of N to our air and water.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for financial support from the Tampa Bay Estuary Program and the University of Florida Center for Undergraduate Research in developing this fact sheet.

References

Jani, J., Y.-Y. Yang, M. G. Lusk, and G. S. Toor. 2020. “Composition of Nitrogen in Urban Residential Stormwater Runoff: Concentrations, Loads, and Source Characterization of Nitrate and Organic Nitrogen.” PLoS One 15(2): e0229715. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229715

Krimsky, L. S., M. G. Lusk, H. Abeels, and L. Seals. 2021. “Sources and Concentrations of Nutrients in Surface Runoff from Waterfront Homes with Different Landscape Practices.” The Science of the Total Environment 750: 142320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142320

Lusk, M. G., P. S. Garzon, and A. Muni-Morgan. 2023. “Nitrogen Forms and Dissolved Organic Matter Optical Properties in Bulk Rainfall, Canopy Throughfall, and Stormwater in a Subtropical Urban Catchment.” The Science of the Total Environment 896: 165243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165243

Muni-Morgan, A. L., M. G. Lusk, and C. A. Heil. 2024. “Karenia brevis and Pyrodinium bahamense Utilization of Dissolved Organic Matter in Urban Stormwater Runoff and Rainfall Entering Tampa Bay, Florida.” Water 16(10): 1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16101448

Poor, N. D., L. M. Cross, and R. L. Dennis. 2013. “Lessons Learned from the Bay Region Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment (BRACE) and Implications for Nitrogen Management of Tampa Bay.” Atmospheric Environment 70: 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.12.030

Poor, N., C. Pollman, P. Tate, M. Begum, M. Evans, and S. Campbell. 2006. “Nature and Magnitude of Atmospheric Fluxes of Total Inorganic Nitrogen and Other Inorganic Species to the Tampa Bay Watershed, FL, USA.” Water, Air, and Soil Pollution 170(1–4): 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-006-3055-6

Poor, N., R. Pribble, and H. Greening. 2001. “Direct Wet and Dry Deposition of Ammonia, Nitric Acid, Ammonium and Nitrate to the Tampa Bay Estuary, FL, USA.” Atmospheric Environment 35(23): 3947–3955. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(01)00180-7

Reisinger, A. J., M. Lusk, and A. Smyth. 2020. “Sources and Transformations of Nitrogen in Urban Landscapes: SL468/SS681, 3/2020.” EDIS 2020(2). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ss681-2020

Strayer, H., R. Smith, C. Mizak, and N. Poor. 2007. “Influence of Air Mass Origin on the Wet Deposition of Nitrogen to Tampa Bay, Florida — An Eight-Year Study.” Atmospheric Environment 41(20): 4310–4322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.08.060

Yang, Y. Y., and M. G. Lusk. 2018. “Nutrients in Urban Stormwater Runoff: Current State of the Science and Potential Mitigation Options.” Current Pollution Reports: 1–16.