The use of educational field trips has long been a major part of the education programming for both youth and adults. However, due to funding limitations, time constraints, and increased liability concerns many education professionals balk at requests for field trips. In spite of these concerns, well-planned field trips can be a valuable tool in the extension agents educational toolbox.

An educational field trip can be an integral part of the instructional program. Good field trips provide participants with first hand experience related to the topic or concept being discussed in the program. They provide unique opportunities for learning that are not available within the four walls of a classroom. An example of this would be a turf grass management program visiting a golf course. A trip such as this would allow participants to see first-hand the many principles of plant growth and management, pest control, and watering techniques discussed in the program.

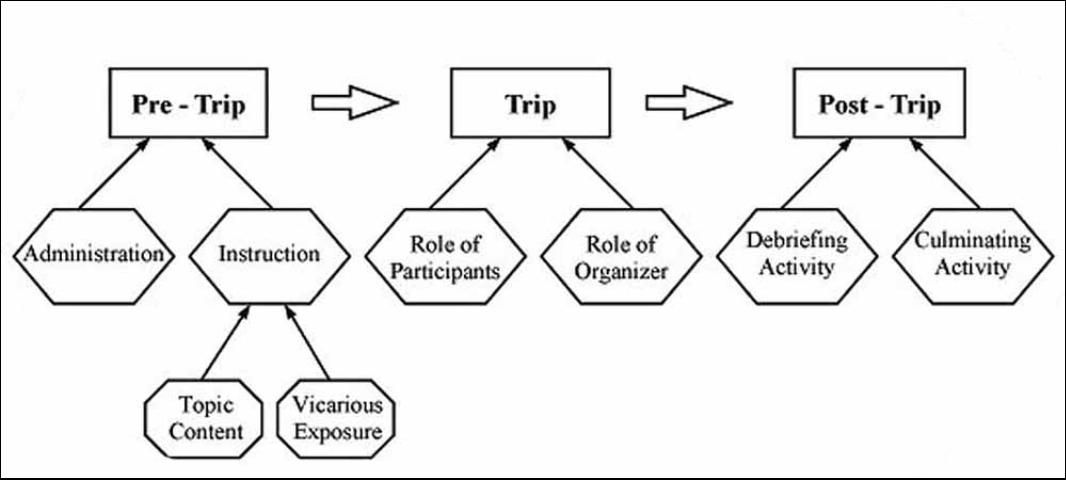

As with any type of educational program component, field trips should be designed around specific educational objectives. A field trip should be designed so participants can easily make connections between the focus of the field trip and the concepts they are learning in the rest of the educational program. Numerous research studies in science education have documented significant increases in participant factual knowledge and conceptual understanding after participation in well-planned field trips. When planning and organizing a successful field trip, three important stages should be included: pre-trip, trip, and post-trip (see Figure 1).

Pre-Trip Stage

The pre-trip stage of a field trip involves two major components: administration and instruction. The administration component involves all of the steps taken by the field trip organizer to arrange the logistics of the field trip. Steps include securing permission from appropriate administration, organizing transportation to and from the field trip location, contacting the field trip location to verify the schedule and activities, and obtaining signed permission slips from parents/guardians of youth attending the field trip. Unfortunately, many field trip organizers only focus on administrative concerns during the pre-trip stage of field trip planning. Although the activities of the administration component are important, if organizers only focus on logistics, a major segment of the pre-trip stage is missing and field trips may not be educationally successful.

The instruction component of the pre-trip stage is critical in preparing participants for the experience. Numerous research studies have shown that participants, especially youth, often have high levels of anxiety when going on a field trip. Anxiety levels can be especially high for field trips to novel, unfamiliar settings. Often a field trip is the first experience a person has with a particular location. When individuals experience high levels of anxiety, learning cannot take place. To reduce anxiety, field trip organizers need to make participants feel comfortable and safe at the location of the field trip just as they would in a typical classroom.

One method of accomplishing this goal is to provide participants with vicarious exposure to the field trip site as part of pre-trip instruction. Vicarious exposure could involve the field trip organizer showing participants photographs, drawings, or a videotape of the site to be visited. This can occur at a meeting prior to the field trip or materials may be sent to participants prior to the event. Another option would be to post important field trip information on the Internet so that participants can visit a website prior to the experience. Items such as the location of restrooms and basic features of the site should be identified. If participants will be at the field trip site during a meal time, such arrangements should also be discussed. Studies in science education have shown time and again that providing participants with vicarious exposure prior to a field trip significantly reduces individual anxiety and increases overall trip effectiveness.

As part of instruction, field trip organizers should also review safety and behavior rules and expectations with youth. These items should also be included in permission slip letters to parents/guardians of youth participants.

To increase the educational effectiveness of field trips, pre-trip instruction should also focus on the content topics and concepts that participants will be investigating during the field trip. It is important for field trip organizers to give participants verbal clues regarding what to look for during their activities. Pre-trip instruction makes it easier for participants to focus on the educational goals of the trip. As part of pre-trip lessons, organizers should demonstrate the use of any equipment and explain in detail any activities that will be occurring during the field trip.

Research has clearly shown that during field trips, learning activities involving groups of 2–3 individuals are most effective. These groups should be assigned during the pre-trip stage. Specific roles of each group member during activities (such as observer, recorder, graphic artist) should also be explained in advance.

Trip Stage

The second stage of a successful field trip is the trip itself. Two components should be addressed during this stage: the role of the participant and the role of the organizer. The role of the participant is accomplished by establishing a field trip agenda and sharing this agenda and field trip objectives with the participants. A suggested agenda for a field trip starts with a brief amount of free time for individuals to explore the field trip site on their own. This open exploration may not be appropriate in all locations. For example, individuals could not roam freely inside an equipment manufacturing plant. They could however, have free time to view items in the visitor area or lobby prior to the guided tour. This exploration time allows participants to get comfortable with their surroundings. Once the basic curiosity of the facility is satisfied, learners are better able to focus their attention on the content topics to be learned.

The second phase on the agenda is often a whole-group guided tour. During the tour, the organizer or tour leader can point out specific items that relate to the educational goals of the trip. This also provides an opportunity for participants to ask any questions they may have developed during their exploration time. The third phase of a suggested field trip agenda is a small group learning activity. Working in pre-assigned groups of 2–3, participants can complete an activity such as a short worksheet or scavenger hunt. The worksheet should be designed in a manner that is challenging to learners yet not frustrating. The worksheet should clearly relate to the educational goals of the field trip.

The role of the organizer is also an important consideration during the trip stage. Although monitoring and management of the experience is important, monitoring participant learning is also a major organizer responsibility. Throughout the field trip, the organizer should be actively engaged in teaching activities. However, on field trips the organizer should utilize different teaching approaches than those used in traditional classroom settings. Organizers should interact with participants to help answer questions they might have. Organizers should also initiate discussion with small groups of participants by asking them questions. During field trips, organizers should function more as facilitators or guides rather than directors. By playing an active rather than a passive role during the field trip, organizers can increase student interest and learning.

Post-Trip Stage

The third and final stage of a successful field trip is the post-trip stage. Like the stages before it, this stage also contains two components: debriefing and a culminating activity. During the debriefing session, participants should be encouraged to share and discuss their experiences during the field trip. This could include sharing and discussing data or results of assigned small group activities as well as sharing feelings about specific aspects of the trip or overall impressions. Participants should also be given an opportunity to identify and discuss problems encountered during the field trip.

The second component of the post-trip stage is a culminating activity. This activity should give participants an opportunity to apply the content knowledge they gained during the field trip. Culminating activities should help learners tie together content they covered in regular educational program sessions and content learned during the field trip. They can be whole group or small group experiences. Both the debriefing and culminating activity should occur as soon after the trip as possible.

Planning and organizing a successful field trip can be a great deal of work for the organizer. However, by following the simple steps in each of the pre-trip, trip, and post-trip stages, your participants can greatly benefit from your labor. Also when a well developed field trip plan is presented to administrators, many of their concerns are usually addressed. Field trips should be an integral part of extension programming. If county faculty properly plan and execute educational field trips everyone can benefit from the experience.