Introduction

Conflict is inevitable in organizations that combine employees, volunteers, stakeholders, and clients of all ages. The Cooperative Extension model is a unique example of a multi-generational organization, particularly the sectors that rely on volunteer assistance like 4-H and Master Gardener Volunteer programs. Extension professionals commonly interact with a variety of generations. Youth participants, adult volunteers, colleagues, and supervisors are just a few of the groups Extension professionals must serve well. Due to interactions with these varied groups, Extension professionals may experience conflict with their stakeholders, volunteers, colleagues, and supervisors. Therefore, they must be able to understand conflict and conflict styles to navigate tense situations.

What Is Interpersonal Conflict?

Conflict is present in all organizations.While conflict has been researched at length, no consensus on a definition exists in the literature (Barki & Hartwick, 2004; Omisore & Abiodun, 2014). Depending on perspective and tolerance for differences, conflict can be defined differently by everyone. For this publication, Rahim’s (2002) conflict definition will be used. Rahim describes conflict as “an interactive process manifested in incompatibility, disagreement, or dissonance within or between social entities” (p. 207).

There are many views and types of conflict. The three most common views of conflict are the traditional, contemporary, and interactionist views (Omisore & Abiodun, 2014). Traditionalists prefer to avoid conflict as it indicates a problem within the group. The contemporary view perceives conflict as a natural occurrence and inevitable when individuals work together. The interactionist view goes one step further than the contemporary view by indicating that conflict is not only a natural occurrence but a necessary step for individual growth and effective performance (Omisore & Abiodun, 2014).

The three primary types of conflict include relationship, task, and process conflicts. Relationship conflicts exist when personalities clash and emotions are involved. Task conflicts include differences of opinion related to work goals and resource distribution. Process conflicts occur when there is disagreement about how to complete a task (Omisore & Abiodun, 2014).

Conflict is not inherently good or bad; instead, conflict is either functional or dysfunctional. Functional conflict can improve group performance and support the goal of the group, as well as can lead to increased learning and new ideas (Myers, 2020). Conflict is dysfunctional when mismanaged, leading to a breakdown in relationships and group performance (Omisore & Abiodun, 2014).

The Importance of Navigating Interpersonal Conflicts

Conflict is an inescapable and often unpleasant part of life at work. It is imperative that team members and managers can handle conflict situations efficiently to avoid the wasted time and job dissatisfaction that result from dysfunctional conflict. For example, the Myers-Briggs Company (2022) reported workplace employees spend an average of 4.34 hours per week dealing with conflict at work. This has increased from a reported 2.1 hours per week in 2008 (Myers-Briggs Company, 2022). Additionally, more time spent dealing with conflict at work correlated with lower job satisfaction and feeling less included at work. When asked, “How does conflict at work usually make you feel?” the most common reported feelings were anxious, depressed, fearful, and stressed (The Myers-Briggs Company, 2022).

The Dual Concern Model of the Styles of Handling Interpersonal Conflict Inventory

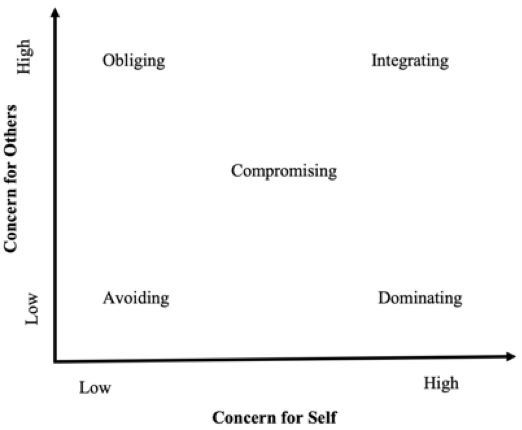

There is no one way to handle conflict. Depending on personalities involved and the conflict topic, a variety of approaches may be used. However, two factors composing conflict— concern for self and concern for others— can eliminate some ambiguity around conflict resolution (Rahim & Bonoma, 1979). The first factor, concern for self, represents the degree to which an individual prefers to satisfy their own interests. The second factor, concern for others, represents the degree to which they prefer to satisfy others’ interests. These two factors converge to create the dual concern model of the styles of handling interpersonal conflict, which has five conflict preferences (Rahim & Bonoma, 1979). This model can be seen below in Figure 1. Each style has benefits and drawbacks and fits appropriately in particular conflict situations. Rahim (2002) provides a brief overview of each of the styles:

- The obliging style is seen when one has high concern for others and low concern for self. This style is demonstrated when one minimizes personal concerns to meet the needs of the other party. This style is best suited when you care more about the relationship than the issue, realize you may be wrong about the issue, or decide the issue is more important to the other party.

- The avoiding style is characterized when one has low concern for self and low concern for others and when individuals fail to meet either party’s needs, resolving when one withdraws or avoids conflict. This style is effectively used when the issue is unimportant, if past tension surrounding this issue needs a cooling-off period, and/or if the potential damage from relationship fallout is greater than the benefit of being right on the issue.

- The compromising style is seen when one has intermediate concern for self and others. It’s most useful when consensus cannot be reached and/or a temporary solution is effective for a longer-term issue. An important point is that in a compromise neither party receives 100% of the desired outcome. Instead, both parties give up something to reach a resolution.

- The integrating style entails a high concern for self and a high concern for others in conflict situations as an effective, solutions-oriented way to deal with complex issues. This style is most useful when there is significant time available to manage the issue due to its extensive nature. The integrating style consists of sharing information, examining alternatives, and potentially creating new, previously unconsidered, solutions so both parties may achieve their desired outcomes. This style is associated with both parties being fully satisfied at the conclusion of the conflict.

- The dominating style is when one has high concern for self and low concern for others, creating win-lose situations where a party will force the other party to agree with their viewpoint or perspective. This style can be used appropriately when others don’t have the knowledge or time to adequately decide for themselves. This style is also effective if the issue is important to you and/or if an unfavorable decision by the other party would negatively affect you.

Credit: Rahim & Bonoma, (1979, p. 1327)

Instrumentation to Measure Interpersonal Conflict Management Style

The Rahim Organizational Conflict Inventory (ROCI) is an instrument for understanding interpersonal conflict management style (Rahim, 1983). The instrument consists of three variations since one’s conflict management styles might differ between a colleague/peer, a supervisor, or an employee/volunteer (Rahim, 1983). The ROCI–II, Form B instrument will help one to understand the conflict management styles of those who manage volunteers. The ROCI consists of 28 statements where respondents should indicate how they handle their disagreement or conflict on a 5-point Likert scale. The following are response options: 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Somewhat disagree, 3 = Neither agree nor disagree, 4 = Somewhat agree, and 5 = Strongly agree.

Interpretation and Application

Extension professionals can utilize the ROCI-II, Form B instrument to assess their preferences and tendencies for dealing with conflict situations involving Extension volunteers. A high average score indicates a stronger preference for a particular style, while a low average score indicates less preference with the corresponding conflict style. Alternatively, a high average score may indicate an overused conflict style, and a low average score may suggest the conflict style is not being used enough. For example, if someone prefers the dominating style, others may perceive that person as challenging to work with. In future conflict situations, a person aware of their preference for the dominating style can take inventory of the situation. Should they use a style that is high concern for self and low concern for others in that moment? Is the situation that critical to their success? Or is this a low-stakes conflict scenario where an individual could shift to a compromising style and gain social capital in the workplace?

No conflict style is universally effective. The value of the ROCI instrument is in the increased self-awareness of the user. When one is aware of how they tend to approach conflict, they can avoid the pitfall of relying too heavily on a single conflict style. With greater awareness of all five conflict styles and their unique benefits, an individual can select the best conflict style to handle each conflict situation.

Extension professionals are uniquely positioned to work with a wide variety of individuals from supervisors to volunteers to external stakeholders. Each person has a different conflict tendency dependent on the audience they are engaging. This is particularly helpful in the Extension context as we are cognizant of our preferences and of how we tend to engage with particular stakeholder groups.

Conclusion

In conclusion, conflict is an inevitable part of life and can lead to personal, professional, and organizational growth. Extension professionals should not fear conflict but rather learn about their personal conflict management style and the styles of those with whom they work – from coworkers to volunteers. By having a strong understanding of conflict components, Extension professionals can manage functional conflict well and reduce the likelihood of dysfunctional conflict destroying relationships, teams, and organizations.

References

Barki, H., & Hartwick, J. (2004). Conceptualizing the construct of interpersonal conflict. International Journal of Conflict Management, 15(3), 216–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb022913

The Myers-Briggs Company. (2022). Conflict at work: A research report. https://www.themyersbriggs.com/en-US/Programs/Conflict-at-Work-Research

Myers, P. (2020). Conflict management is of global importance today. Medium. https://medium.com/swlh/conflict-management-is-of-global-importance-today-436dfb2f08dc#:~:text=Functional%20Conflict%20%E2%80%94%20This%20type%20of%20conflict%20is,conflict%20supports%20the%20main%20purposes%20of%20the%20organization

Omisore, B. O., & Abiodun, A. R. (2014). Organizational conflicts: Causes, effects and remedies. International Journal of Academic Research in Economics and Management Sciences, 3(6), 118–137. http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJAREMS/v3-i6/1351

Rahim, M. A. (1983). Rahim Organizational Conflict Inventories–I & II. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Rahim, M. A. (2002). Toward a theory of managing organizational conflict. International Journal of Conflict Management, 13(3), 206–235. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.437684

Rahim, M. A., & Bonoma, T. V. (1979). Managing organizational conflict: A model for diagnosis and intervention. Psychological Reports, 44(3), 1323–1344. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1979.44.3c.1323