The urban tree canopy offers many proven benefits for communities by providing shade, improving air quality, assisting with stormwater runoff, raising property values, enhancing the look and feel of communities, improving the health of residents, and providing wildlife habitat. Adding and maintaining trees on properties can help reduce residential utility bills. In 2016, the residents of Gainesville, FL, saved about 7.7 million dollars in total heating and cooling costs because trees help regulate shifts in temperature through the summer and winter (Andreu et al., 2019). Urban trees also provide places to gather and socialize outdoors, spaces where residents can decompress and recover from daily stress, and opportunities for children and youth to engage with and learn about nature (Tyrväinen et al., 2005). With more than 90% of Florida’s population living in urban areas, preserving and expanding urban tree canopy can benefit current and future Floridians. Actions aimed at achieving increased urban forest cover depend on science-based management decisions. The Florida Cooperative Extension Service (CES) can bridge the informational and educational needs of cities working towards building up their urban forestry programs. This publication is for Extension agents and the stakeholders they partner with in urban forestry, parks and recreation, and urban greening and urban tree management roles in cities or municipalities. The professional titles vary, but these individuals all work to support goals related to building and maintaining a healthy and sustainable urban forest. This publication can also help communities working with these actors to better understand the collaborative and iterative process of developing Extension tree stewardship programs.

Municipal urban forestry programs often face limitations in funding, time, and staffing (Cadaval et al., 2024). Trained tree stewards can help address these gaps by supporting various aspects of urban forest management. These knowledgeable volunteers contribute to tree planting and maintenance, educate community members about trees, and advocate for the protection and expansion of urban forests. By engaging the public in tree care and education, tree stewardship also extends the capacity and impact of Extension educators. Moreover, stewardship fosters a strong connection between urban forestry efforts and the values and needs of local communities. For new Florida residents, local tree stewards serve as valuable guides to the state’s diverse tree species and regional growing conditions.

County Extension offices are often the first stop for residents seeking information and advice about urban forestry topics. Extension can support the development of stewardship programs by identifying local needs to inform tree managers and community members of potential collaborative opportunities that promote urban forestry initiatives. Extension can also train stewards and serve as a continual resource, ensuring the most up-to-date research is communicated to communities. This publication will highlight how the Florida Cooperative Extension Service is essential in advising and educating residents and decision-makers about keeping the urban forest healthy and growing and leveraging community engagement skills and practices to recruit and train stewards. Insights from past research on improving tree stewardship in Tampa, FL (Monaghan et al., 2013), and other literature on tree stewardship shaped our recommendations for establishing future programs. Previous research assessing residential preferences and interests in tree planting and maintenance activities in Tampa, FL, worked to engage neighbors and partners and created opportunities to listen and recognize the barriers to participating in stewardship. This research highlighted actionable ways future programs may start.

Extension-Supported Tree Stewardship to Empower and Build Resilient Communities

Tree stewardship goes beyond planting trees. It is a long-term and shared responsibility between residents and public institutions to care for the urban tree canopy. Tree stewards can be trained volunteers who support urban forestry efforts through the selection, planting, and maintaining of trees. Tree stewards can also play an important role in educating others and modeling tree care techniques and pro-urban forestry behaviors. Tree stewards can advocate for the prioritization of urban forests for the benefit of local communities, supporting a healthier urban environment for current and future generations. While individual tree stewards (including residents, landlords, businesses, churches, and organizations) may take “ownership” over the care of specific trees, ideally, they will operate as part of a comprehensive community stewardship effort. This publication is intended for Extension agents and the many tree advocates they can bring together, including groups such as homeowners associations (HOAs) and urban neighborhood associations, civic groups, elected officials, and municipal staff. When these partners build tree stewardship programs based on local needs and community goals, they foster programs that are sustainable and fun. Most of the urban tree canopy lies within private property and along the rights of way within residential districts. Therefore, initiatives to plant, establish, and maintain urban trees must be clearly tied to private and community interests and capabilities. Many cities and counties offer tree planting programs where residents can request a tree be planted in the public right of way in front of their home. However, these planting programs can fall short of desired outcomes, resulting in dead trees and frustrated residents. Similarly, community groups such as neighborhood associations may want to improve their tree canopy but are unsure how to do this in a coordinated, large-scale effort. To ensure tree planting programs are successful, the tree stewardship approach focuses on empowering residents to properly care for their trees through targeted education, engagement, and technical support.

Several cities use tree giveaway programs to incentivize tree canopy growth on private property. However, challenges remain in engaging all residents through these programs. For example, residents may not be inclined to engage in stewardship when they perceive a lack of support for tree maintenance or feel they are not included in conversations where decisions about trees are made (Carmichael & McDonough, 2019). Understanding local ecological and social contexts facing communities can be critical to supporting effective and engaged stewardship.

Around the United States, there are several programs run and sponsored by organizations and institutions at local, city, state, or multistate levels (Table 1). In the state of Florida, for example, two Extension programs in Duval and Sarasota Counties have organized and trained local volunteers to maintain and advocate for trees in their communities. In a survey of tree steward volunteers in Duval County, FL, stewards expressed that they believed they were making a difference in improving their urban forest and they enjoyed socializing and working together (Figart, 2019). In 2025, the UF/IFAS Urban Forestry Extension Council will launch a new statewide program called Florida Tree Stewards. This program will train volunteer coordinators around the state to develop local tree stewardship groups that address community urban forestry goals. The Florida Tree Stewards program is designed to incorporate local needs. Volunteer trainers and coordinators may include Extension agents, municipal arborists or urban foresters, and others.

Table 1. Examples of different approaches to and scales of tree stewardship programs across North America.

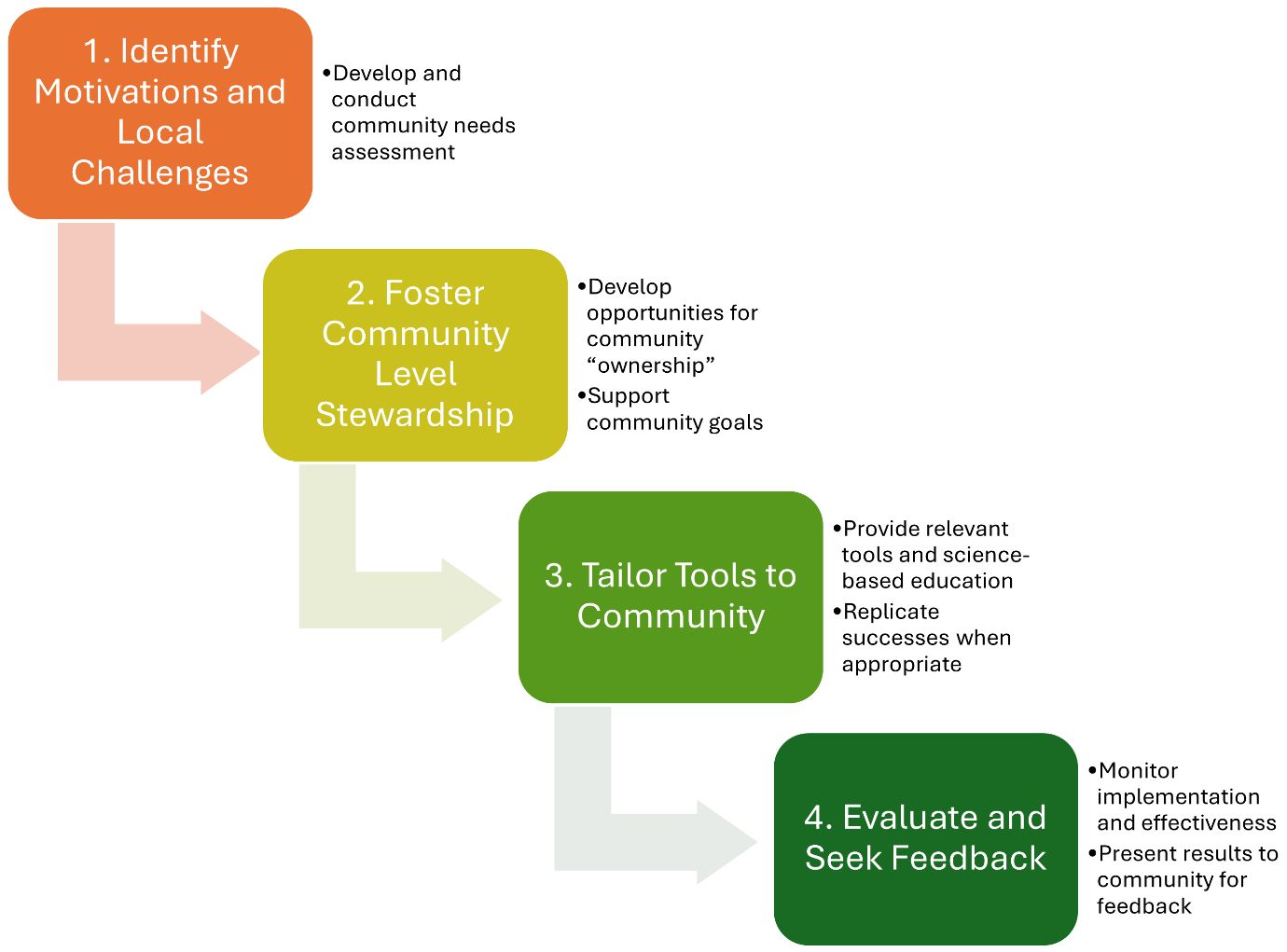

Extension agents provide an important link among university researchers, city governments, and residents by serving as a trusted information resource. Extension agents can gather community data, provide educational workshops, organize stewardship activities, and foster partnerships that strengthen existing municipal urban forestry programs. As Extension agents play the role of “convener” and educator, they can help partners build trust, share in decision-making, and commit to objectives. Below, we highlight four steps similar to those found in most effective Extension programs but are unique to the needs of communities that want to work collaboratively for a healthier and expanded urban tree canopy.

Steps to Developing Successful Tree Stewardship Programs through Extension

Credit: Stephanie Cadaval, UF/IFAS

Step 1: Identify Motivations and Local Challenges

A recent survey of Florida residents indicated a common appreciation of urban trees with most desiring more trees in their neighborhoods (Koeser et al., 2024). Floridians largely associate trees with shade, connection to nature, and beauty or aesthetics (Koeser et al., 2024). However, residents also share safety and other concerns about trees. Trees on residential properties age and require continued care and monetary investment that many residents do not anticipate. Storm events (e.g., hurricanes) heighten concerns about trees causing damage to buildings and raising insurance rates. Perennial safety concerns are about obscuring street signs, and causing damage to sidewalks, roads, and powerlines (Escobedo et al., 2009).

Communities will need to weigh their preferences about trees and ways they can use trees to address local needs. For example, spaces shaded by vegetation can provide a sense of community and social cohesion in neighborhoods (Clarke et al., 2023). Residents may prefer that trees are planted in specific locations to create a promenade or a shady gathering place in a park. One community may favor fruiting trees to establish a “food forest” while another community may select trees based on beauty or historic or cultural relevance.

By surveying residents using various methods, agents can gain important insights about how public space is currently used and valued by the community. For example, Extension agents and state specialists collaborated with the Tampa Urban Tree Program to research ways to increase engagement with residents (Monaghan et al., 2013). Focus groups revealed residents wanted more input and flexibility for planting trees in their neighborhoods; they felt they lacked a basic understanding of tree selection and care. Residents desired greater coordination among infrastructure activities and city projects (i.e., road expansion, powerlines and storm damage mitigation) that can negatively impact the tree canopy. City projects that remove old oak trees, for example, can have a negative impact on how residents view their government's commitment to preserving neighborhood identity. In response to residents’ requests, the City of Tampa expanded the number of tree species available for right of way planting projects and initiated interdepartmental coordination and review processes for city-sponsored projects that impact neighborhood trees. To address the educational needs reported by residents, the city and UF/IFAS Extension organized a neighborhood tree steward program to teach the fundamentals of tree selection, planting, establishment, and long-term care.

The needs of communities can be assessed through surveys, discussions at neighborhood meetings, formal and informal interviews with residents and community leaders, or focus groups. Needs assessments can be conducted and recorded by agents, university faculty, stakeholder groups, and the community members themselves. The findings from needs assessments should be shared with participants and interested parties to support open dialogue and trust building. The community’s needs may not all be met through an urban tree planting program, but understanding needs and finding ways to address them is a critical first step towards developing a sense of community ownership and investment in tree stewardship.

Step 2: Foster Community-Level Stewardship

Stewards may be motivated to participate in programs by the opportunity to build community with their neighbors (Reidman et al., 2022). Stewardship programs contribute to community social cohesion, and trained stewards provide technical expertise to ensure tree survival. Every newly planted tree requires additional care and resources until it becomes established. One study found tree mortality was three times higher among trees that were not cared for by trained stewards (Boyce, 2010). Another study found that trained volunteers contributed positively to the overall survival of maintained trees, especially when these stewards worked alongside local institutions or municipal crews (Roman et al., 2015). Extension can support tree stewards by training volunteers in proper watering and soil management techniques for newly planted trees, identification of potential tree health problems and threats, and reporting processes to notify tree care professionals within Extension and the city government of those issues.

To help foster community-level stewardship, Extension can sponsor community tree planting events (when residents collectively plant many trees in one day) and ongoing volunteer opportunities. With training and guidance, volunteers can also map and inventory trees in their neighborhoods with tools such as Open Tree Map, which integrates citizen-based data collection with formal inventory and assessments conducted by the city government. In many older and underserved neighborhoods, there is often a historic tree canopy that lacks mapping, evaluation, and restoration plans. Tree mapping is a tool that helps communities identify and plan where trees are needed. When paired with tree assessments, mapping and inventorying trees allows communities to make informed decisions about current and future tree management. While many volunteers may be motivated by their desire to work with nature, they are also often interested in improving their neighborhoods.

Additionally, involving youth in volunteer or internship programs is an effective way to support urban tree advocacy in communities. It can also open up green job opportunities for young people (Roman et al., 2015). Educational and outreach activities can appeal to a wide range of age groups including youth and families. Tree scavenger hunts or tree tours (guided and self-guided) invite residents to interact with nature in a fun way and learn about the benefits of trees. Activities like tree tours can be organized and facilitated by trained tree stewards. These types of community volunteer opportunities can result in broader support for trees as well as improved awareness about trees (Austin, 2002).

Step 3: Provide Tools That Are Tailored to the Needs of Communities

Extension can use community research and science-based education to provide tree steward programs with the tools they need to be successful. For example, from the focus groups held in Tampa, FL, residents reported facing numerous barriers to irrigation such as investment of time, energy needed to transport water (through buckets or hoses), the need to remember when and how much to water, and concern about increased water bills. Residents who report lacking time, energy, or other resources, such as elderly or working residents, may struggle to overcome barriers to proper irrigation and tree establishment. Providing residents with tools such as water bags and rain barrels to collect rainwater for irrigation may help lower some of these barriers. Some cities provide water trucks to irrigate newly planted right of way trees. Text message reminders to provide water for tree establishment can work for some audiences. Programmatic changes such as planting trees right before the rainy season can also help (Monaghan et al., 2013). Other tree survival issues can be addressed through effective tree staking, proper fertilization, or providing communities with personal protective equipment (PPE), tools, and equipment.

Extension agents are uniquely positioned to understand the need for tailored solutions through their knowledge of the community, local contacts, and university resources. They can also disseminate these solutions using their established communication networks. Extension agents and their resources in the land-grant institution can help with grant applications and strategic planning specific to identified urban forest initiatives (e.g., young tree watering, structural pruning, sampling palms for lethal bronzing). Strategies and best practices may, in some cases, be replicated from tree stewardship programs in other cities if they fit the unique barriers and opportunities of the local community.

Step 4: Evaluate and Seek Feedback

Careful monitoring of tree health and survivorship (number of trees remaining alive) (van Doorn et al., 2020) paired with program evaluation can show impacts on communities (Gariton et al., 2022) and inform decision-making. The community will be able to judge the value of their tree care management activities and provide this information to their partners to enhance decision-making at all levels, from governments to funding agencies, non-profits, and neighborhood associations.

Few activities are as important to the success of a community-based urban forest program as monitoring, but this step is often overlooked or poorly designed (Northrop et al., 2022). Taken from adaptive management approaches in urban forestry, the community should institute two forms of monitoring in association with the tree stewardship program: implementation and effectiveness. The implementation monitoring will determine if the community is implementing their tree steward program as designed. It asks, “Did we do what we set out to do?” Effectiveness monitoring will determine if the action achieved the stated goal or objective. It asks, “Did it work?” The community members, participating organizations, government agencies, and funders can decide on the metrics to be used in these evaluations.

Measuring the success of the program (separate from tree survivability) can be important for learning what works and how to avoid pitfalls. Every tree stewardship program will encounter challenges, as partners may have different goals or funding mandates, resident groups may undergo leadership changes, or communication breakdowns may occur between parties. Depending on what is important to the program, a tree stewardship evaluation could measure participant demographic information, knowledge gained, changes in attitudes, levels of engagement, or enthusiasm for the program. One measure could be whether residents were motivated to buy and plant more trees on their own or to help their neighbors with tree issues.

Ultimately, success can be measured by a larger and healthier tree canopy that is supported and enjoyed by the community. Therefore, collecting data on tree health and survivorship is key both in the beginning and throughout the stewardship program. This data can reveal challenges at a microscale and suitability of a tree to the location. For example, monitoring can reveal if there is a need for a different tree species, whether a tree is adding services or disservices to a community, or if the tree is in a site more susceptible to vandalism. Even more importantly, tree monitoring data informs how future tree plantings may be planned and how trees may be managed or maintained on a broader urban scale. Researchers and practitioners should work together to develop standardized protocols and identify what data should be collected to develop a robust data set that can inform and improve the tree stewardship program (Roman et al., 2013).

Whatever the chosen metrics, the final step in any evaluation design is to present the results back to community members and stakeholders for their feedback. This can be done through project reports, Extension fact sheets, social media, community potlucks, and commission meetings.

Conclusion

Urban trees benefit new and long-term Florida residents. As part of the urban green infrastructure in cities, trees help to reduce utilities costs, provide shade, contribute to stormwater management, and improve air quality. Urban trees also support community health and well-being. The urban tree canopy provides economic, social, and environmental benefits, but needs special knowledge, buy-in from communities, and strong partnerships for successful management. Cooperative Extension has the skills and tools (including the support of scientists at the land-grant university) to assemble and facilitate a community-centered approach to urban forestry through tree stewardship. Extension is ideally suited to encourage tree stewardship and document successes because it tracks and incorporates important information about communities as part of its needs assessment processes (e.g., participant engagement, experiences, willingness to participate, motivations, etc.) to refine programming and strengthen partnerships.

Cooperative Extension plays a connective role, empowering communities to care for their urban tree canopy through trusted education, engagement, and collaboration. Extension agents are vital to building trust among stakeholders and supporting decision-making about trees. Their involvement can tailor solutions to community needs, assist with grant applications, and share information through communication networks. Agents may also support tree health monitoring and evaluate program effectiveness, ensuring the sustainability of tree stewardship initiatives for the future. Tree stewardship is more than planting trees. It is a long-term commitment to building community networks that strengthen and expand the urban ecosystem. The four-step approach outlined in this publication — identifying motivations and challenges, fostering community-level stewardship, offering tailored tools, and evaluating impact — provides a flexible, actionable framework for developing successful programs. As the Florida Tree Stewards program launches, agents across the state can help determine local priorities and support communities’ capacities to build a more resilient urban forest.

References

Andreu, M., Hament, C. A., Fox, D., & Northrop, R. J. (2019). Values and ecosystem services of Gainesville’s urban forest in 2016: FR345/FR414, 7/2019. EDIS, 2019(5). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-fr414-2019

Austin, M. (2002). Partnership opportunities in neighborhood tree planting initiatives: Building from local knowledge. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, 28(4), 178–186. https://doi.org/10.48044/jauf.2002.026

Boyce, S. (2010). It takes a stewardship village: Is community-based urban tree stewardship effective? Cities and the Environment, 3(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.15365/cate.3132010

Cadaval, S., Clarke, M., Roman, L. A., Conway, T. M., Koeser, A. K., & Eisenman, T. S. (2024). Why can't we all just get along? Conflict and collaboration in urban forest management. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, 50(5), 346–364. https://doi.org/10.48044/jauf.2024.018

Carmichael, C. E., & McDonough, M. H. (2019). Community stories: Explaining resistance to street tree-planting programs in Detroit, Michigan, USA. Society & Natural Resources, 32(5), 588–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2018.1550229

Clarke, M., Cadaval, S., Wallace, C., Anderson, E., Egerer, M., Dinkins, L., & Platero, R. (2023). Factors that enhance or hinder social cohesion in urban greenspaces: A literature review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 84, 127936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2023.127936

Escobedo, F., Northrop, R., Orfanedes, M., & Iaconna, A. (2012). Comparison of community leader perceptions on urban forests in Florida: FOR230. EDIS.

Escobedo, F., Seitz, J., Northrop, R., & Moon, M. (2011). Community leaders’ perceptions of urban forests in Hillsborough County, Florida: FOR194. EDIS.

Figart, L. (2019). The Tree Steward Volunteer Pruning Program in Jacksonville, Florida. In Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society (Vol. 132, pp. 215–216). https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/20220226318

Gariton, C., Lamm, A., Israel, G., & Diehl, D. (2022). Raising the quality of Extension reporting: An evaluation leadership team model: WC412/AEC751, 3/2022. EDIS, 2022(2). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-wc412-2022

Koeser, A. K., Gilman, E. F., Paz, M., & Harchick, C. (2014). Factors influencing urban tree planting program growth and survival in Florida, United States. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 13(2), 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2013.12.001

Koeser, A. K., Hauer, R. J., Andreu, M. G., Northrop, R., Clarke, M., Diaz, J., ... & Zarger, R. (2024). Using the 3-30-300 Rule to assess urban forest access and preferences in Florida (United States). Arboriculture & Urban Forestry. https://doi.org/10.48044/jauf.2024.007

Monaghan, P., Northrop, R., Banks, D., Ott, E., Johnson, T., & Beck, K. (2013). Mobilizing community support and advocacy for urban forestry: Final project report and recommendations.

Nesbitt, L., Meitner, M. J., Girling, C., & Sheppard, S. R. (2019). Urban green equity on the ground: Practice-based models of urban green equity in three multicultural cities. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 44, 126433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126433

Riedman, E., Roman, L. A., Pearsall, H., Maslin, M., Ifill, T., & Dentice, D. (2022). Why don’t people plant trees? Uncovering barriers to participation in urban tree planting initiatives. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 73, 127597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127597

Roman, L. A., McPherson, E. G., Scharenbroch, B. C., & Bartens, J. (2013). Identifying common practices and challenges for local urban tree monitoring programs across the United States. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, 39(6), 292–299. https://doi.org/10.48044/jauf.2013.038

Roman, L. A., Walker, L. A., Martineau, C. M., Muffly, D. J., MacQueen, S. A., & Harris, W. (2015). Stewardship matters: Case studies in establishment success of urban trees. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 14(4), 1174–1182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2015.11.001

Tyrväinen, L., Pauleit, S., Seeland, K., & De Vries, S. (2005). Benefits and uses of urban forests and trees. In Urban Forests and Trees: A Reference Book (pp. 81–114). https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-27684-X_5

van Doorn, N. S., Roman, L. A., McPherson, E. G., Scharenbroch, B. C., Henning, J. G., Östberg, J. P., ... & Vogt, J. M. (2020). Urban tree monitoring: A resource guide (Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-266). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station. https://doi.org/10.2737/PSW-GTR-266