Introduction

Manually washing the rhizomes of ginger and turmeric (Figure 1) is a labor-intensive process that adds significantly to the cost of final harvested products. Commercially available automatic cleaning equipment makes the postharvest process easier, but only at a price and scale that would benefit large-scale operations.

Without automated equipment, large clumps of soil must be separated at harvest (rough cleaning), followed by a more direct washing of rhizomes (fine cleaning). Fine cleaning ginger and turmeric can be challenging because of the irregular shape of rhizomes and the delicacy of the skin (especially for ginger). Even after two stages of cleaning, rhizomes still need to be trimmed of roots and divided into saleable units before going to market.

Credit: Paul Fisher, UF/IFAS

Our objective was to design and test rhizome cleaning equipment aimed at small farmers and to compare this with manual cleaning. From 2020 to 2024, we grew ginger and turmeric crops in trenches or 16 gal containers in tunnel greenhouses at the UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center in Live Oak, Florida, and at the UF main campus in Gainesville, Florida. We tracked labor hours for rough cleaning (removing clumps of soil to prepare for washing) and fine cleaning (washing and removal of roots). Fine cleaning involved manual washing or using a semi-automated process designed by students from the UF/IFAS Department of Agricultural and Biological Engineering. We also observed manual and automated harvest and cleaning at commercial operations in Hawaii. The project was funded by a Specialty Crops Block Grant from USDA-ARS and the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, as well as the UF/IFAS SEEDIT program for emerging crops.

This publication describes tips for harvest and presents designs of cleaning equipment that are easy for a small farmer to build and maintain while reducing labor costs.

Preparation

To facilitate harvest, stop irrigating plants at least two weeks before harvest to dry the soil and shoots. Remove dried shoots with shears, a hedge trimmer, or mowing equipment (Figure 2).

Credit: Paul Fisher, UF/IFAS

In the field, lift rhizomes with a tractor-drawn sweet potato harvester or similar. In a tunnel or for container-grown crops, remove plants manually by hand or with a garden fork (Figures 3 and 4).

Credit: Paul Fisher, UF/IFAS

Credit: Paul Fisher, UF/IFAS

Rough Clean

After lifting the plants, rough cleaning involves manually removing large chunks of soil before washing (Figure 5).

Credit: Jacob Muller, UF/IFAS

Our estimate from two years in two Florida locations for the manual rough cleaning is shown in Table 1, with an average of 31.8 lb per person hour at a cost of $0.47 per pound, assuming a labor cost of $15 per hour, which is based on the adverse effect wage rate in Florida for 2024.

Fine Cleaning

A simple but labor-intensive way to fine clean rhizomes is using hose water pressure and removing soil by hand (Figure 6).

Credit: Paul Fisher, UF/IFAS

As an alternative to manual fine cleaning, we designed and tested two pieces of cleaning equipment: a barrel washer and a bubbling reservoir, which are described in later sections of this publication. The barrel washer is designed to wash off most of the soil from the rhizomes after the initial harvest. The bubbling reservoir helps remove leftover material and serves as a staging place for rhizomes to rinse while they are being trimmed of roots and stems.

Trimming and Curing

The final part of the cleaning process is to trim the roots (Figure 7), wash the rhizomes in a 50-ppm chlorinated solution or diluted hydrogen peroxide, dry the outside of rhizomes to form a decay-resistant skin, and store them at around 55°F and 85% humidity (Figure 8). (See EDIS publication EP638, “Ginger, Galangal, and Turmeric Production in Florida,” for other postharvest tips.)

Credit: Paul Fisher and Raúl Cabezón, UF/IFAS

Credit: Raúl Cabezón and Paul Fisher, UF/IFAS

Labor Cost

Manual fine cleaning (including trimming and curing) averaged 7.6 lb per person hour. The cost of harvest can be added to the cost of manual fine cleaning, as shown in Table 1, thus totaling $3.17 per pound.

Table 1. Labor cost to rough clean and manually fine wash rhizomes. Fine washing included trimming and curing.

With the machine-washing system, a team of four people was able to produce 40 lb of fine-cleaned ginger and turmeric rhizomes per hour, or 10 lb per person hour, including trimming and curing. Based on this analysis in Table 2, adding the automation equipment would save approximately $1 per pound compared with manual washing and would require 23% less labor. Add the $0.47 of rough cleaning to both manual or machine washing for the total price per pound. Manual cleaning also used a lot of water, around 600 gal per hour, compared with 180 gal per hour when machine washing (about two-thirds less water).

Table 2. Comparison of the labor cost of fine washing (including trimming and curing) using manual or machine processes.

As shown in Tables 3 and 4, the cost of building both the barrel washer and bubbling reservoir was approximately $635 for parts and $150 for 10 hours of labor, totaling $785. These calculations assume that a grower already has a suitable air compressor (which is a general piece of equipment for many processes). Equipment consist of common materials that are easy to find online or at local hardware stores, and many small farmers would already have some of these components on hand.

Using both the barrel washer and bubbling reservoir together gave the best results, but the barrel washer provided the greatest cost benefit in reducing manual labor. In one 40-hour week, a person could fine clean 400 lb of rhizomes with both pieces of machinery, compared with 304 lb if washing manually, at a labor cost in both cases of $600 ($1.50 per pound for machine washing or $2.48 per pound for manual washing as shown in Table 2). The machinery would pay for itself in terms of labor savings after processing 800 lb (in about two weeks).

Design: Barrel Washer

Credit: Jacob Muller, UF/IFAS

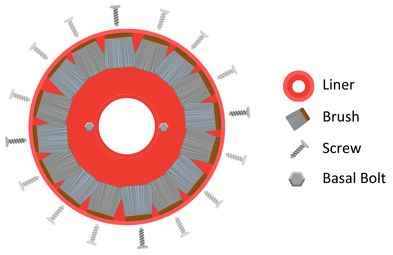

The barrel washer (Figure 9) is a concrete mixer adapted to have an internal liner (from a flexible plastic tub) that holds the rhizomes and coarse brushes that wash off large chunks of soil. Water is added to partially fill the washer, and around 5 lb of rhizomes are placed inside.

Build Considerations

There are a few things to keep in mind when building your own barrel washer.

The measurements in this guide are relative to the parts we used in our design. If you do not have the same components we used, you will need to adjust the dimensions to fit your needs.

When picking a concrete mixer (Figure 10), try to find one that has an outer “dome” that can be removed from the main body. This makes it much easier to insert the liner and brushes.

We recommend using a flexible plastic tub as a liner (Figure 11) because it eliminates the need to attach brushes directly to the concrete mixer. Not only will this maintain the integrity of the mixer, but it will also allow you to pull the tub out for more thorough cleaning. The tub we purchased was slightly taller than the interior of the mixer and had plastic handles, but we easily cut down and removed the handles and excess plastic to make the liner fit with the dome on top. The tub must fit flush or snug with the upper dome piece of the mixer so that even if there is some gap space, the rhizomes will not get trapped or lost.

Credit: Jacob Muller, UF/IFAS

In our design, we use two types of brushes with differing bristle length and rigidity to provide a tumbling effect of the washer, but the following design assumes one brush length for simplicity. Suitable brushes are sold in a hardware store as “bench,” “yard,” or “bristle” brushes or brooms (Figure 11). The brushes do not have to be soft, but they should also not be so rough that they strip the skin off the rhizomes. The exact number of brushes you need will depend on the plastic tub’s diameter and the brush head length.

Credit: Jacob Muller, UF/IFAS

Table 3. Parts list and approximate cost for the barrel washer (items ordered from local hardware stores). This budget is based on 2024 prices.

Tools & Construction

Tools: Box cutter, drill, saw, screwdriver, socket wrench, tape measure, and marker

1. Mixer

- Assemble the concrete mixer according to the manufacturer’s directions.

- In the unit we modified, there were two bolts (see Figure 12, right) at the bottom of the mixer base that are used later to attach the flexible tub liner inside. Remove those bolts for now.

- Do not add the mixer outer dome yet (see Figure 10, left). The outer dome will be added at the end in Stage 4.

- Your mixer will likely come with a large, round rubber sealer that goes in between the mixer base and the outer dome. Do not lose this part; you will need it later.

Credit: Jacob Muller, UF/IFAS

2. Inner Tub Liner

- Angle the mixer fully upward and check that the flexible tub sits snug inside the mixer.

- Align the liner with the mixer base. Our mixer unit had a small, raised bump on the bottom of the interior. To fit the liner around the bump, we cut a 6 ¼" diameter hole into the center of the bottom of the liner (Figure 12, left).

- Cut the tub to size if needed. Our tub was slightly too tall, so the dome could not fit when placed back on the mixer with the liner inside. Using a sharp knife, we reduced the height of the tub until it fit inside the mixer (in our case, 14" tall).

- Drill mounting holes. When the liner fits well inside the mixer, prepare it for mounting. Keeping the liner sitting inside the mixer, mark the bottom of the liner through the holes where the two bolts should be. Then, remove the liner and drill the holes to bolt size. Do not attach the liner to the mixer base yet. Leave these bolts aside until Stage 4: Assembly.

3. Brushes

- Prepare the brushes (Figure 11).

- Remove any pole or handles from the brushes to produce a smooth rectangular base that can be screwed flush with the liner.

- Evenly space the brushes around the inner circumference of the liner. Avoid gaps between brushes where rhizomes can get caught.

- Orient all brushes so that they run vertically up the interior sides of the tub.

- Attach brushes to the tub. Working one at a time, press and hold each brush firmly in position against the bottom of the tub and drill a small pilot hole through the side of the tub for the screw. Drill in from the outside, roughly ¼" to ½" from the top edge of the brush. Try to avoid drilling all the way through the brush.

- Then, follow with drilling in the exterior screws. By the end, the outside of the tub will look somewhat like Figures 14 (right) and 15.

Credit: Jacob Muller, UF/IFAS

Credit: Jacob Muller, UF/IFAS

Credit: Jacob Muller, UF/IFAS

4. Assembly

- Mount the liner: Now is the time to use the two bolts left from Stage 1.

- Start by pushing the bolts through the holes drilled in the liner, so that the ends stick out the bottom. Attaching the liner is usually easiest when the mixer is pointed directly upward, and the bolts are already pushed into the liner.

- Place the liner into the mixer base by aligning the bolts from the liner with the holes at the center-bottom of the mixer.

- Nudge the bolts into place and tighten (Figure 12, right).

- Attach the mixer dome according to the manufacturer’s directions. Do not forget to add the large rubber sealer between the mixer base and the upper dome in the concrete mixer.

- The final product should look like Figure 16. Brushes line the entire interior of the tub, the tub is secured firmly in place, and the mixer dome is properly attached. Your new barrel washer is ready to go!

Credit: Jacob Muller, UF/IFAS

Design: Bubbling Reservoir

Credit: Jacob Muller, UF/IFAS

The bubbling reservoir is a basin with a water source and rolling bubbles from an air compressor. This machine is used at the cleaning stage after the barrel washer. Partially cleaned rhizomes can be dumped into this reservoir and then removed for final trimming, sanitation, and drying.

Build Considerations

A suitable reservoir will be spacious enough to hold up to 5 lb of rhizomes from the barrel washer. We opted to use a 20 gal parts washer from the local hardware store because it had the added benefit of legs that elevated it to a comfortable working height. Using a parts washer specifically is not necessary. All you need is some form of tub or basin that can be elevated off the ground to reduce back strain from leaning over.

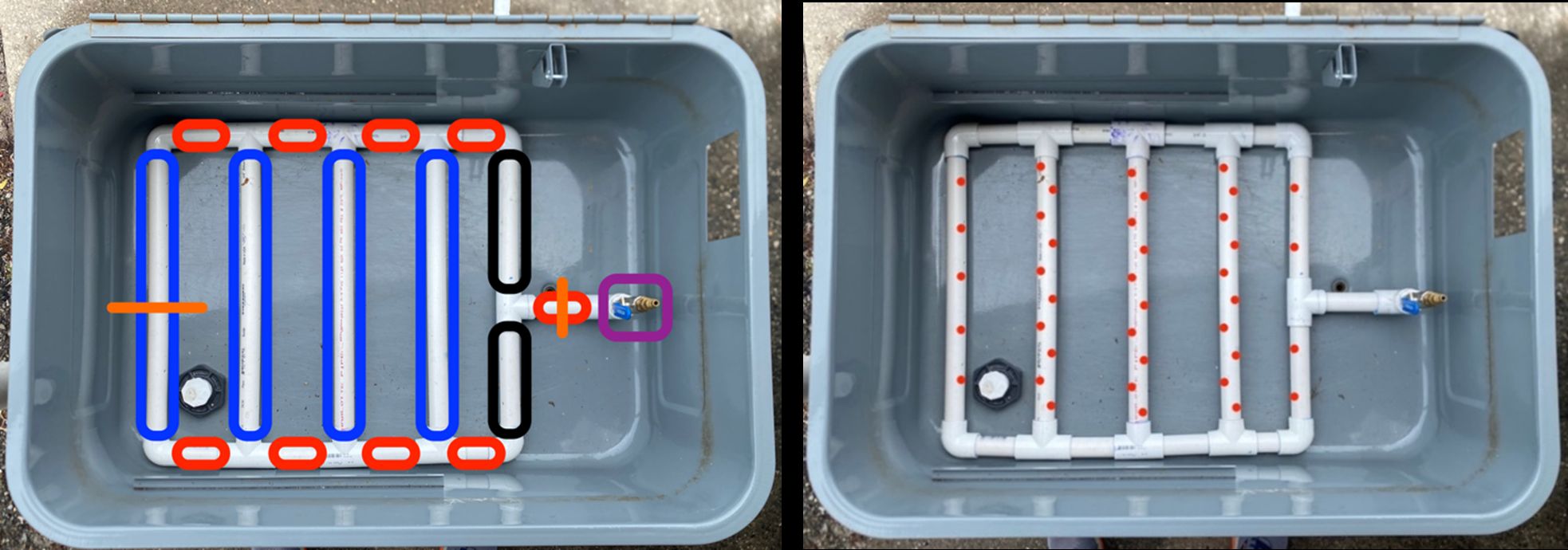

The design of the PVC bubbling lines may vary slightly depending on the size and shape of your chosen reservoir.

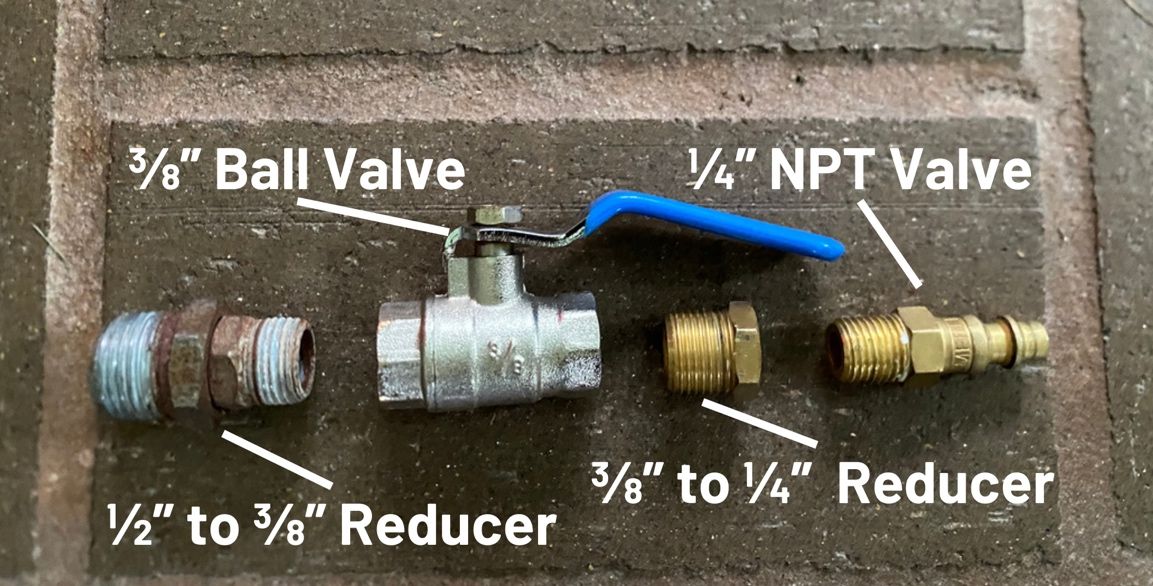

You will need to create an adapter to connect the PVC pipe to the air compressor. The parts list describes the basic components of this adapter, but the goal is to connect the PVC pipe to a valve and the valve to your air compressor hose. See Figure 18 for more details.

Table 4. Parts list for bubbling reservoir (items ordered from local hardware stores). Cost assumes the small farmer already has an approximately 200 psi air compressor. For your safety, use a compressor that has a built-in pressure relief/cutoff. This budget is based on 2024 prices.

Tools & Construction

Tools: Air compressor (~200 psi), drill, hole saw drill attachment, PVC cutter, tape measure

1. Washer

- Assemble the parts washer according to the manufacturer’s directions.

- Leave out any interior pieces and/or pump assemblies, if applicable. You only need the metal body and legs.

2. Air Compressor Adapter

- Connecting the air compressor hose to the PVC frame will require an adapter (Figure 18). The valve is also useful for controlling the bubbling without going directly to the compressor. Connect the parts according to Figure 18.

- PVC is not made to maintain air pressure. Do not connect the air compressor until Stage 3, where a significant number of holes are made in the PVC frame.

Credit: Jacob Muller, UF/IFAS

3. PVC Frame

- Sizing: The PVC frame should be built to fill most of the space inside the reservoir.

- Cut the PVC: For our 20 gal reservoir, we cut the PVC tube into the following sizes (Figure 19):

- Nine 3 ½" pieces

- Two 7 ¼" pieces

- Four 16" pieces

- Dry fit the PVC: Before using glue, dry fit the PVC tubing using the guide in Figure 19 (left) so you can be sure all the components fit well together.

- Use the tees and elbows to connect all the parts together.

- For the pieces that lead away from the frame and connect with the air compressor, point the leftover elbow upward and insert the ¾" to ½" PVC reducer. The air compressor adapter from Stage 2 should now be able to connect to the frame.

- Make sure the whole frame fits properly in the reservoir.

- PVC Cementing: When ready, disassemble and piece the frame together again using the PVC primer and cement. For best results, let the cement set for at least two to three hours. DO NOT glue the adapter to the PVC.

- PVC Frame Attachment: After the frame is fully assembled and the glue is given time to cure, the frame can be attached to the reservoir using the two ¾" pipe straps.

- Place one strap across the 3 ½" tube that connects to the adapter and a second strap over the 16" tube farthest away from the adapter. See the two lines marked on Figure 19 as a guide.

- Bubbling Holes: Drill small, alternating ⅛" holes into the topsides of each long center span of the PVC tubes, using the dots in Figure 19 (right) as a guide.

- Drain Installation: Adding a larger drain is a good idea if the built-in basin drain will clog easily with a lot of soil. Once the PVC frame is in place, you can choose any appropriately sized section to place your drain.

- Using the hole saw, cut into one of the empty sections at the bottom of the tub.

- Install the drain piece.

Credit: Jacob Muller, UF/IFAS

4. Assembly

- If you have not already done so, connect the air compressor adapter to the PVC frame and close the valve.

- Attach the air compressor hose to the adapter.

- Fill the reservoir with water and test the bubbling by adjusting the valve. It should look similar to a rolling boil.

- If the bubbles seem too large, try adding another hole to each of the PVC center spans. If there is not enough bubbling and the valve is open all the way, you may need a stronger air compressor.

Operation

Now that you have successfully built your rhizome washers, you are ready to get started! An adept team of four can run Stages 1–3 simultaneously, but team members should take some time to get familiar first.

1. Rough Clean

Avoid dumping entire pots directly into the barrel washer. Before adding rhizomes, knock off any loose substrate and break apart any large chunks into more manageable sizes with a rough cleaning. Splitting the rhizomes into small pieces is not necessary, but removing the excess substrate now will speed the cleaning in the barrel washer.

Credit: Jacob Muller, UF/IFAS

2. Spin Cycle with the Barrel Washer

Adjust the barrel washer to a high angle and begin filling it with water. Fill until it is near overflowing.

Start the barrel washer and place rhizomes into the machine. With our 16 gal pots, adding half of the rhizomes (about 5 lb) per cycle was the right amount for cleaning. Leaving space for the rhizomes to toss around is important, so underloading is better than overloading.

Depending on how much substrate is on the rhizomes, the “spin cycle” will run for about three to seven minutes.

Credit: Jacob Muller, UF/IFAS

When rhizomes are sufficiently clean, turn off the motor and wait for the spinning to stop. Remove the rhizomes from the washer by hand or by turning the barrel downward and dumping directly into a sieve. There should be little to no substrate left.

3. Fine Clean with the Bubbling Reservoir

Add rhizomes to the bubbling reservoir. While submerged in water, the rhizomes will roll around and lose matter that may still be clinging on. Though not as impressive as the barrel washer, it eliminates the need to rinse off rhizomes after they come out of the washer.

Remove one rhizome at a time from the bubbling reservoir and clip off the roots and stems. Skim off floating material from the reservoir water when there is too much in the way.

Now, they are ready to go! Remember to treat and store rhizomes properly (see Trimming and Curing) to preserve your hard work!

4. Maintenance

Thoroughly spraying out the inside of the barrel washer is enough to clean it on a day-to-day basis. Remove the dome from the mixer and pull the tub out for a more comprehensive cleaning on a semi-regular basis. The same goes for the bubbling reservoir—remove the PVC frame and give the basin a good rinse from time to time. Both can be stored outside in a covered area.

Conclusions

Innovative small farmers can easily adapt, design, and build simple machinery similar to the barrel washer and bubbling reservoir. This low-cost equipment can reduce labor by 24% and water use by two-thirds compared with manual cleaning. The labor cost of harvest is the biggest obstacle to the profitability of ginger and turmeric as alternative crops for Florida growers. Ginger is challenging to clean because of its irregular shape and soft skin. These equipment designs are meant to combat such challenges but could easily be used for other root vegetables.