Introduction

This publication describes Florida residents’ perceptions of heat-related illnesses (HRI), their perceived knowledge about HRI, and trusted sources when seeking information about HRI. This resource was developed to help Extension faculty better understand how Florida residents think about rising temperatures and HRI so they can better support their clientele through education and communication.

Heat-Related Illnesses in Florida

HRI refers to any condition caused by the body's inability to cool itself. It can cause sickness and death, especially in Florida, where the heat index can exceed 90 degrees even in winter (Vaidyanathan et al., 2020).

The most common forms of HRI include heat exhaustion and heat stress. Heat exhaustion is typically marked by symptoms such as heavy sweating, nausea, dizziness, weakness, and muscle cramps. Heat stress, although often used as an umbrella term, generally refers to the physiological burden imposed on the body by external heat, which may progress to more severe outcomes such as heat stroke, a life-threatening condition characterized by confusion, loss of consciousness, and potential organ failure (Vaidyanathan et al., 2020; Mitchell et al., 2019).

Heat-related illness can affect any individual, whether they spend their time outside or indoors, but particularly those who spend most of their time in the sun. Young, healthy individuals such as laborers, military recruits, and athletes represent distinct populations at risk for exertional heat-related illness. Risk factors include lack of acclimatization, poor physical health, and being overweight. In addition, weather conditions (air temperature, radiant heat, humidity), level of physical activity, and hydration status also affect a person’s risk for heat-related illness (OSHA, 2023).

Background (Methods)

The information shared in this publication was collected through an online survey conducted in December 2023 by the UF/IFAS Center for Public Issues Education in Agriculture and Natural Resources (PIE Center) in partnership with the Southeastern Coastal Center for Agricultural Health and Safety (SCCAHS). A total of 500 Floridians 18 years and older responded to the survey. Respondents were representative of the Florida population based on the 2020 U.S. Census.

Results

To better understand perceptions of HRI, respondents were asked about their overall knowledge of heat-related illnesses, knowledge of HRI symptoms and preventative actions, trusted sources of information on heat-related illnesses, and level of concern about heat-related illnesses. The majority of respondents were concerned about HRI and considered themselves knowledgeable but were unaware of protective behaviors.

Knowledge of HRI

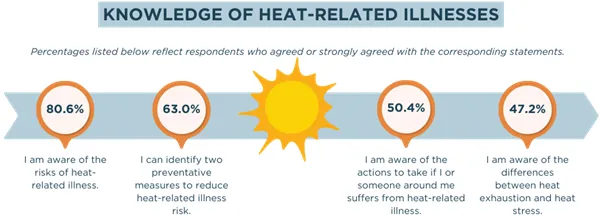

Self-perceived knowledge was examined by providing respondents with several statements related to HRI knowledge and awareness and asking respondents to indicate their level of agreement on a six-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Slightly disagree, 4 = Slightly agree, 5 = Agree, 6 = Strongly agree). The majority (80.6%) of respondents felt knowledgeable about the risks of heat-related illnesses (Figure 1). Sixty-three percent of Floridians felt they could identify two preventative measures to reduce heat-related illness risk. However, just over half (50.4%) of respondents were aware of the actions to take if they or someone around them suffered from a heat-related illness. Less than half (47.2%) of respondents were aware of the differences between heat exhaustion and heat stress.

Credit: Ashley McLeod-Morin, UF/IFAS

Trusted Sources of Information

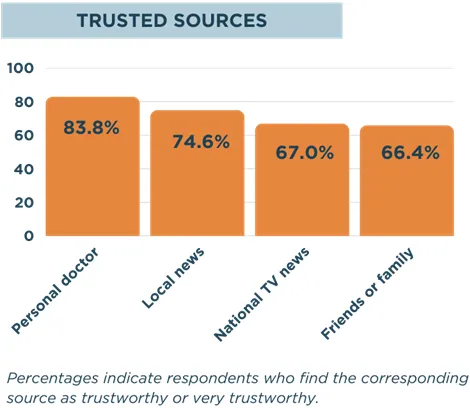

Respondents were provided a list of extreme heat and/or HRI information sources and asked to indicate their level of trust on a five-point scale (1 = Very untrustworthy, 2 = Untrustworthy, 3 = Neither, 4 = Trustworthy, 5 = Very trustworthy). When receiving information about heat-related illnesses or extreme heat, the greatest number of respondents found the following sources trustworthy or very trustworthy (Figure 2): personal doctor (83.8%), local news (74.6%), national TV news (67.0%), and conversations with friends or family (66.4%). The smallest number of people indicated trust for social media sites, including Facebook, Instagram, X (formerly Twitter), and TikTok.

Credit: Ashley McLeod-Morin, UF/IFAS

Seeking Information about HRI

Respondents were also asked about their information-seeking behaviors related to HRI. When asked how frequently they sought information about extreme heat or HRI, a little over 60% of respondents indicated never or rarely seeking information about the topics between June 2023 and December 2023. However, if respondents were to actively search for information (Figure 3), they were likely or very likely to use their personal doctor (74.4%), Department of Health websites (63.4%), and friends or family (60.2%).

Credit: Ashley McLeod-Morin, UF/IFAS

Respondents indicated valuing the opinions of health professionals, scientists, and family members regarding heat-related illness. Despite indicating they valued and trusted the opinions of health professionals, only 16% of respondents indicated they had heard or seen information regarding heat or heat-related illnesses from their personal healthcare provider in the past six months.

Recommendations

The responses from this survey indicate Floridians lack specific knowledge and do not typically seek information about HRI, even though they are concerned about it. This presents an opportunity for Extension and strategic partners to inform Floridians about important protective behaviors during times of extreme heat.

As Extension faculty deliver programs related to safety and/or health practices, including equipment safety or chronic disease prevention, they can include heat safety messages and resources. For example, the importance of drinking a sufficient amount of water can relate to both HRI prevention and the benefits of a healthy diet.

Extension could partner with state agencies, such as the Florida Department of Health, or local medical facilities to develop media campaigns that inform Floridians about the dangers of extreme heat, the difference between heat stress and heat exhaustion, and what to do if they or someone around them suffers from a heat-related illness. The media campaign should focus on a grassroots approach and provide information to local news outlets. Social media could be used to inspire information-seeking behaviors but should not be the cornerstone of a campaign since Floridians may not trust information on social media, as indicated in responses from this survey.

Health departments and local health professionals could be valuable partners for Extension because Floridians trust these sources and seek information from them. Local Extension may already have established relationships with these partners in some locations and could provide educational materials they use in their own programs, such as printed fact sheets or brochures, to be shared at health clinics or doctor offices.

The Southeastern Coastal Center for Agricultural Health and Safety has curated and developed several heat safety resources, including infographics available in English and Spanish and a heat safety plan template that organizations can adapt to fit their environment. These resources and more are available at Heat-Related Illness Resources from SCCAHS.

References

Mitchell, R. C., Irani, T., Arosemena, F. A., Pierre, B., Bernard, T. E., Grzywacz, J. G., & Morris, J. G. (2019). SCCAHS 2019-02. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida/Southeastern Coastal Center for Agricultural Health and Safety.

OSHA. (2023). US Department of Labor cites Okeechobee labor contractor after heat illness claims the life of 28-year-old farmworker in Parkland. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. https://www.osha.gov/news/newsreleases/region4/06282023?itid=lk_inline_enhanced-template

Southeastern Coastal Center for Agricultural Health and Safety. (n.d.). Heat-Related Illness Resources from SCCAHS. https://www.sccahs.org/index.php/resources/heat-related-illness/

Vaidyanathan, A., Malilay, J., Schramm, P., & Saha, S. (2020). Heat-Related Deaths — United States, 2004–2018. MMWR. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6924a1