This publication is intended to be a resource for Florida blueberry growers to use in scouting for disease and insect/mite pest damage; managing disease, insect/mite pests, and weeds; and application of certain plant growth regulators. It is intended for use only as a guide. Specific rates and application methods are on the pesticide label, and these are subject to change at any time. Always refer to and read the pesticide label before making any application. The pesticide label supersedes any information contained in this guide, and it is the legal document referenced for application standards.

Florida Blueberry Disease and Insect Pests by Stage of Plant Development

Dormant Plants

PHYTOPHTHORA ROOT ROT

Phytophthora root rot (PRR) is considered the most serious soilborne disease that affects southern highbush blueberries (SHB). Some SHB cultivars are considered tolerant and others highly susceptible, while rabbiteye cultivars are less affected by the disease. PRR is caused by the oomycete pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi. Common aboveground symptoms associated with Phytophthora infections are reductions in plant vigor and premature fall discoloration. Symptoms at ground level and belowground include crown and root rots. Disease on susceptible hosts occurs when certain environmental conditions (primarily a saturated root zone and root wounding) trigger Phytophthora reproduction, infection, and symptom development. PRR is typically more severe in low and poorly drained areas of a farm. The pathogen causes root discoloration (dark brown to black, instead of the normal cinnamon brown) and decay. Advanced stages of infection cause plant stunting, wilting, an abnormal or reduced root system, root rot, and plant dieback. Leaf discoloration also typically occurs, including yellowing, reddening with or without marginal burn, abnormal growth of new leaves, and defoliation. Plants affected by PRR may also be more susceptible to other dieback diseases including stem blight. Fungicides with the active ingredient mefenoxam, such as Ridomil Gold SL, are recommended where PRR occurs and are applied twice yearly (typically in January and June) through drip irrigation or as a band application directly to the bed. In addition to the phenylamide fungicide mefenoxam, which is applied to the soil, Aliette (Fosetyl-Al 80%) and numerous phosphorous acid products, referred to as “phites” or phosphonates, provide some control when applied as summer foliar sprays. A new fungicide (within the FRAC group 49) with reported Phytophthora efficacy is available for use on blueberry. Oxathiapiprolin is available in the product Orondis® Gold 200 or as premix with mefenoxam in the product Orondis® Gold (Premix). These products have not been evaluated on SHB in Florida; thus, look for additional information on these products as data becomes available. See Table 1.

BLUEBERRY GALL MIDGE

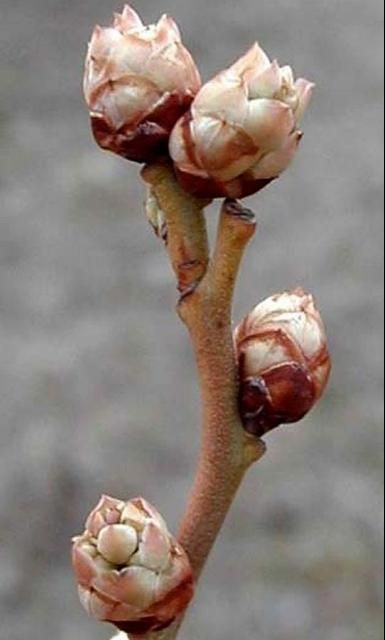

The blueberry gall midge (BGM) is a tiny fly whose larvae feed on vegetative and floral buds. Typically, gall midge will attack young developing floral and leaf buds, which will cause floral buds to abort or fall off the bush, resulting in poor flowering and “fruit set.” With heavy gall midge injury to floral buds, there would be a lighter bloom. Instead of the usual five to six buds producing several flowers, only two may reach maturity, resulting in poor fruit clusters. Blueberry gall midge will also feed on leaf or vegetative buds, leaving young leaves deformed and misshaped. Gall midges lay eggs on warm winter days and at any time during the growing season when the plants are making new flushes of growth. Delegate® (Spinetoram), Exirel® (Cyantraniliprole), diazinon, Apta® (Tolfenpyrad), and Movento® (Spirotetramat) can be applied for gall midge control between flower bud stages 2 and 3 (Figures 2 and 3). Application should take place when the most mature buds first show slight scale separation. Sprays may need to be repeated during warm spells. Bud scale separation may occur as early as December 15th in north Florida. Among rabbiteye cultivars, 'Premier' is often particularly attractive to the gall midge and is a good sentinel variety to monitor. Gall midge sprays can also suppress a prebloom thrips population. See Table 2 and EDIS publications ENY-2105, “Management of the Blueberry Gall Midge on Southern Highbush Blueberry in Florida” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/in1414) and ENY-997, “Blueberry Gall Midge on Southern Highbush Blueberry in Florida” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN1239).

IMPORTED FIRE ANTS

Ant baits employed in early spring as a broadcast treatment usually eliminate most, but not all, fire ant mounds within treated areas. Under high ant pressure, treating a second time in the fall provides better fire ant control. Most ant baits are slow acting and require up to eight weeks to control active mounds because they interfere with reproduction, causing a gradual colony die-off. Extinguish® Professional Fire Ant Bait (0.5% methoprene) is labeled for use on all crop land sites. It is effective but somewhat slower acting than Esteem® Ant Bait (0.5% pyriproxyfen). In order for the bait to be effective, active ant foraging is essential. Worker ants must be attracted to baits so that they will carry the baits back to their colonies. Ideally, temperatures should be warm and sunny. Ant baits work best when the soil is moist but not wet. Avoid applying ant baits when conditions are expected to be cold, overcast, rainy, or very hot. Individual mound treatments are most effective when used as needed for the occasional colony that survives broadcast treatments. Mound treatments using insecticide baits should be applied in a circle 3–4 feet from the mound. Baits should not be placed directly on top of mounds because the colony will move the queen to safety if mounds are disturbed. See Table 2.

SCALE

Scale insects injure blueberries by sucking plant sap, inserting their mouthparts into a plant, and remaining immobile throughout their lives. Signs of infestation are leaf yellowing (chlorosis), defoliation, fruit drop, sooty mold, branch dieback, or plant death. Soft scales (Coccidae) secrete a waxy covering over the body. They also secrete a large amount of sugary waste (honeydew) resulting in sooty mold, which can interfere with photosynthesis and slow plant growth. Of the soft scales, Indian Wax scale (Ceroplastes ceriferus (Fabricius) and Florida wax scale (Ceroplastes floridensis) are the most prolific on blueberries in Florida. See Table 2 and EDIS publication ENY-2094, “Wax Scale on Southern Highbush Blueberry in Florida” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN1387).

Prebloom through Green Tip (Leaf Buds) and Pink Buds (Flower Buds)

PHOMOPSIS CANE AND TWIG BLIGHT

Phomopsis cane and twig blight is a fungal disease caused by Phomopsis vaccinii, which spreads to uninfected plants by wind and rain. Characteristic symptoms are dark-brown lesions on fruiting twigs (often surrounding floral buds), dieback of young twigs, and the shriveling of flower and fruit clusters on diseased stems. Dying tissue may spread down the twig until most of the flower buds on an individual twig die. Shriveling of flowers and fruit clusters may appear similar to Botrytis damage. Control measures include fungicide applications and pruning out infected twigs. See Table 1.

BLUEBERRY GALL MIDGE

See previous discussion (in the Dormant Plants section).

10%–20% Bloom through 80%–90% Bloom

ALTERNARIA AND ANTHRACNOSE FRUIT ROTS

Alternaria fruit rot occurs most frequently when fruit is not timely harvested and remains on the bush for too long. Symptoms include dark-green to black sporulation on ripe fruit and sunken areas near the calyx end of the berry. In postharvest storage, green-to-gray fuzzy growth may appear on infected fruit, especially if the berries have remained wet or were not properly cooled. Preventive fungicide applications can be made to help minimize disease development.

Anthracnose fruit rot is also referred to as "ripe rot." Infection may occur as early as bloom, with symptoms appearing as the fruit begins to ripen. These symptoms include shriveling; development of sunken lesions; soft, rotted fruit; and eruption of orange- or salmon-colored spore masses on the blossom end of the fruit. In some cases, symptoms do not appear until after the fruit is harvested and stored. Fungicide applications from bloom through harvest prevent significant ripe rot losses most years when coupled with frequent hand-harvesting and rapid-cooling practices that are standard for southern highbush blueberry growers in Florida. Preharvest fungicides are especially important in years where there is a high incidence of disease in the field coupled with warm, wet weather, which can promote disease development. The Blueberry Advisory System (available as an app and on the AgroClimate website (http://cloud.agroclimate.org/tools/bas/dashboard/disease) can help growers with decisions on when to apply fungicides based on when the risk for disease development is higher. See Table 1 and EDIS publication PP337, “Anthracnose on Southern Highbush Blueberry” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/PP337).

BOTRYTIS BLOSSOM BLIGHT

Botrytis blossom blight, caused by the fungus Botrytis cinerea, most commonly infects and blights wounded or senescent (aged past maturity) plant tissues. As a blueberry bush blooms, corollas (the fused petal of the flowers) senesce and become quite susceptible to infection. Ideally the corolla should drop from the flower after pollination but before senescence occurs. Frost damage on tender new growth may wound the plant, delay petal drop, and facilitate infection by the fungus. The development of Botrytis blight, like many other foliar fungal diseases, is highly dependent on environmental conditions. During bloom, periods of low temperatures combined with extended periods of high relative humidity result in more than 24 hours of leaf wetness and increase the likelihood of significant disease development. If the blight continues, an entire cluster of berries can be aborted. When disease is severe, berry reduction can become economically important. Infected berries are sometimes deformed and may develop further rot if environmental conditions later become favorable for disease. After pollination of a flower and drop of the corolla, the risk of infection of the developing fruit is reduced. Economic loss due to Botrytis can be minimized by limited use of irrigation for freeze protection and judicious fungicide applications. See Table 1 and EDIS publication PP198, “Botrytis Blossom Blight on Southern Highbush Blueberry” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/PP119).

FLOWER THRIPS

These are small insects (i.e., 1/16 of an inch in length), yellowish to orange in color with fringed wings. Flower thrips damage blueberry flowers in two ways. Larvae and adults feed on all parts of the flowers, including ovaries, styles, petals, and developing fruit. This feeding damage can reduce the quality and quantity of the fruit produced. Females damage the fruit when they lay their eggs inside flower tissues. The newly hatched larvae bore holes in the flower tissues when they emerge. Flower thrips can be very damaging to flower buds and blooms. Thrips numbers typically increase dramatically as corollas open and bloom progresses. Determining when or if blueberries should be treated for thrips is difficult. Blueberries are a pollination-sensitive crop, and misuse of insecticides and subsequent bee kill can easily impair pollination and ruin fruit set. Only select insecticides (such as Delegate®) should be used during bloom. If Delegate® is used, the insecticide should be applied in the early morning or late evening and be given three hours of drying time before bees are allowed to forage on the crop. To measure treatment thresholds for southern highbush and rabbiteye blueberries, begin sampling bloom clusters as soon as the flower begins to open. Sample four to five areas in a 1-acre block by placing a white sheet under a flower cluster and tapping lightly. Count the number of flowers and count the number of thrips dislodged from the flower cluster. If you average more than four thrips (southern highbush) or three thrips (rabbiteye) per flower, some type of management is recommended. Alternatively, two white sticky traps could be used to monitor a 5-acre block (one on the border and one in the center). If you have more than 80–100 thrips (southern highbush) or 60–70 thrips (rabbiteye), then some type of management tactics are needed. Assail® and Apta® are the material of choice until five days prebloom. See Table 2.

Petal Fall through One Month after Bloom

ALTERNARIA AND ANTHRACNOSE FRUIT ROTS

See previous discussion (in the 10%–20% Bloom through 80%–90% section).

PHYTOPHTHORA ROOT ROT

See previous discussion (in the Dormant Plants section).

BLUEBERRY GALL MIDGE

See previous discussion (in the Dormant Plants section).

CRANBERRY FRUITWORM, CHERRY FRUITWORM, AND PLUM CURCULIO

Review field histories and scout fields for fruitworms and plum curculio to determine if and when spraying is needed. In Florida production areas, plum curculio has not been found to be a pest of southern highbush and rabbiteye blueberries. Fields with a history of infestation should be sprayed at least twice on a 7-to-14-day interval, beginning immediately after bloom. Check for fruitworms twice a week from full bloom until four weeks after petal fall. Examine fruit clusters for tiny pin-sized holes in berries and for frass and premature ripening in more mature fruit. Break berries open to look for larvae and damage. Early varieties are normally infested first. Control will be best when these insects are sprayed early in the infestation period. See Table 2.

Preharvest Fruit

ALTERNARIA AND ANTHRACNOSE FRUIT ROTS

See previous discussion (in the 10%–20% Bloom through 80%–90% section).

Harvested Fruit

ALTERNARIA AND ANTHRACNOSE FRUIT ROTS

See previous discussion (in the 10%–20% Bloom through 80%–90% section). Pre- and postharvest rots can be greatly reduced by timely, complete harvest of all ripe fruit on the bush, followed by rapid postharvest cooling. For hand-harvested highbush and southern highbush cultivars, harvest all ripe berries on the bush every seven days or less. Rabbiteye cultivars should be clean-harvested every 10–14 days. Postharvest cooling is critical and is best accomplished through the use of partial-vacuum or forced-air systems that use fans to pull cold air through stacks of palletized fruit. See Table 1.

BLUEBERRY MAGGOT

Blueberry maggot (BBM) is only a problem for growers north of the Lake City and Live Oak areas. Growers in Gainesville and south of Gainesville should not experience any problems with blueberry maggot. Blueberry maggot is a late-season pest. If berries are infested with BBM, a whitish maggot will appear in the fruit at harvesting. The adult fly that lays the eggs can be monitored by hanging yellow sticky traps (baited with ammonium acetate) within the bush canopy, at least one per cultivar. Trap catches indicate when adults are present. Traps should be hung in the planting when berries begin to turn from full green to the greenish-pink stage. See your county Extension agent for identification pictures and further reference. If your planting has a history of BBM infestation, spray as soon as adults are trapped. Once spraying for BBM begins, it is very important to spray every 7–14 days until all the fruit has been harvested. Materials and spray intervals are listed in Table 2. All growers in Florida who are shipping blueberries to California, Canada, or the United Kingdom must comply with appropriate guidelines for scouting, spraying, and postharvest inspection of berries, including a protocol for cooking samples of harvested fruit to test for the presence of the maggot in berries. The California and Canadian protocols state that blueberries must be certified maggot-free to enter Canada. See Table 2.

DIAPREPES (CITRUS ROOT WEEVIL)

Diaprepes larvae damage blueberry plants by feeding on the roots, including holes and channeling in the roots as well as feeding injury and girdling near the crown of the plant. Note that this damage is frequently observed some period of time after the larvae begin to feed on the roots, and at that point, damage near the crown can appear similar to the effects of root girdling or mechanical wounding and abrasion. These injuries can kill or cause serious decline in blueberry plants and may also create an entry point for Phytophthora, causing a root rot infection. Management and control should target both the adult and larval stages. Control for adults consists of foliar insecticide sprays every 10–14 days when adults are active, beginning when three or more adults are found within 1-acre blocks. Larvae can be managed with insecticides either by directly drenching the soil area beneath the plant canopy or by applying them through drip or microjet irrigation systems. In addition, entomopathogenic nematodes may have potential for controlling root weevil larvae in blueberry. See Table 2 and EDIS publication ENY-999, “Diaprepes Root Weevil on Southern Highbush Blueberry in Florida” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN1241).

FLATHEADED BORERS

Flatheaded borers are a species of beetle in the Chrysobothris genus. The larvae tunnel through plant canes, ultimately killing the cane and acting as an entry point for disease. It is possible that adult beetles are attracted to stressed or damaged blueberry canes, with adult females laying eggs on the injured area and larvae excavating tunnels just beneath the bark. Peak adult activity for Chrysobothris species in north-central Florida is between April and May depending on spring temperatures. There is evidence that beetles are moving from adjacent woodlands into blueberry plantings. This is a relatively new pest in blueberry, and research is ongoing regarding its life cycle, monitoring and trapping protocols, and control measures. See Table 2.

SPOTTED WING DROSOPHILA

Spotted Wing Drosophila (SWD) have been caught in all principal blueberry counties in Florida. Adults lay eggs in ripening blueberries, and larvae develop inside the berry, making the fruits soft and unmarketable. Adults can be monitored by placing traps in blueberry bushes. Traps can be made from plastic cups and baited with yeast sugar water. Traps should be placed within the canopy of the blueberry bush and not in direct sunlight. Recently, a new red sticky Trece trap baited with Trece lures has been shown to catch flies earlier in the season than the traditional Scentry trap with the Scentry lure. However, the Scentry trap still caught as many or more SWD than the Trece trap. A number of insecticides have recently been registered for control of SWD. See Table 2 and EDIS publication ENY-861, “Spotted Wing Drosophila in Florida Berry Culture” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN839).

Postharvest Plants

ALGAL STEM BLOTCH

Algal stem blotch is a blueberry disease caused by the parasitic green alga Cephaleuros virescens Kunze, and it has become a significant disease on southern highbush blueberries in Florida. The alga is thought to enter the plant through natural wounds and openings, through pruning cuts, or by direct penetration of the cuticle. Early symptoms include small red blotches or lesions on green juvenile stems, with lesions expanding to form irregular cankers that can encircle canes. Bright-orange, felt-like mats or tufts of algal growth appear from the lesions on young stems and older cane surfaces during summer and early fall when conditions are hot and humid. Leaves on symptomatic canes bleach white to pale yellow, and growth of the entire plant can be severely stunted as the disease advances. Leaf yellowing tends to occur on a few canes of each plant and is less uniform and blotchier than symptoms of nutritional deficiency. Algal stem blotch can lead to increased susceptibility to Botryosphaeria stem blight, in some cases leading to plant death. Plants that are stressed by abiotic or biotic factors are more susceptible to infection and subsequent disease development. To date, no systemic pesticide products have been found that will kill the algae living underneath the plant epidermis. Spray applications of copper-containing fungicides can help to reduce algal sporulation and protect healthy canes from infection for a few days after application. However, these applications do not impact existing symptoms or eradicate the disease. See Table 1 and EDIS publication PP344, “Algal Stem Blotch in Southern Highbush Blueberry in Florida” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/PP344).

ANTHRACNOSE LEAF SPOT, RUST, SEPTORIA, AND TARGET SPOT

Anthracnose, Septoria, rust, and target spot can cause premature defoliation, resulting in poor bud development and subsequent loss of yield. Fungicide timing for leaf spots varies across the state and by specific disease. Septoria can occur prior to harvest through late spring. Anthracnose leaf spots and target spots generally start postharvest and persist through summer. Rust is a problem in all Florida production areas and in the evergreen system is primarily present during the late fall and winter months. On susceptible varieties, rust can prematurely defoliate plants. Where leaves are not dropped in winter (such as in the evergreen system), rust can carry over on the previous year's foliage and cause related problems in early spring as well. Bravo Weather Stik® is labeled for control of both rust and Septoria leaf spots; this chlorothalonil product makes an excellent rotation partner for the strobilurin-containing products Abound® or Pristine®. However, Bravo Weather Stik® can only be used after harvest because chlorothalonil will damage fruit. See Table 1 and EDIS publication PP348, “Florida Blueberry Leaf Disease Guide” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/PP348). Resistance is known to occur in anthracnose pathogens in Florida. Follow product recommendations for resistance management including observing total fungicide active ingredient limits per season (total of all products with any particular a.i.), limiting consecutive applications of the same active ingredient, practicing rotation of products with different mode of action groups, and using label recommended rates.

AZALEA CATERPILLAR

The azalea caterpillar, Datana major, can be found in Florida from late summer to early fall on blueberries. Immature caterpillars are around 1/2 inch long and reddish to brownish black with yellow and white stripes. Mature caterpillars are about 2 inches long and black with yellow-to-white stripes and a reddish head and legs. If left uncontrolled, a significant infestation can defoliate much of a plant. Although these caterpillars seldom kill the plants they feed on, the stress caused by defoliation can reduce flowering or fruiting the following spring. See Table 2.

BACTERIAL SCORCH (XYLELLA)

Bacterial leaf scorch is caused by Xylella fastidiosa in the southeastern United States. Symptoms begin as a marginal-irregular leaf scorch (browning or necrosis), which may appear similar to symptoms of bacterial wilt or drought stress. Symptoms are initially observed on leaves attached to individual stems or groups of stems on one side of a plant. Plant vigor is reduced, stems and twigs of some varieties such as 'Meadowlark' turn a distinctive yellow color, and the plants eventually die. Diseased plants are typically observed randomly scattered throughout a field, rather than in distinct circles or groups within a row. Infected plants should be removed and destroyed. This bacterial pathogen is vectored by insects called sharpshooters and spittle bugs, including the glassy-winged sharpshooter. Research into the management is lacking, but the disease may be reduced by controlling the vector with suggested insecticides.

BACTERIAL WILT (RALSTONIA)

Symptoms of bacterial wilt are similar to those of bacterial scorch, exhibiting signs of drought stress such as wilting and marginal leaf burn. Infected plants may also be more susceptible to developing severe symptoms of other stress diseases, such as Botryosphaeria stem blight, and therefore may show symptoms of both diseases. Crowns of plants with bacterial wilt have a mottled discoloration or light-brown to silvery-purple blotches with poorly defined borders (distinct from the discoloration associated with stem blight, which is typically pie-piece-shaped and pecan brown in color). Wood chips floated in water from the crowns of plants with bacterial wilt will stream bacterial ooze (unlike plants with bacterial scorch or stem blight). Ralstonia can be spread easily in water, in soil, or through infected plant material, and infected plants may not initially show symptoms. Ralstonia can survive for years in soil, slowly spreading down and across rows of blueberry, leaving large circular patches of dead and dying plants. Where the bacterium is detected, remove and burn or deep-bury infected plants. Then, use soil drenches of products with phosphorous acids or their salts to help protect surrounding plants or any replants from infection. Anecdotally, this practice has helped, but only in preventing new infections, and additional research is needed. See Table 1 and EDIS publication PP332, “Bacterial Wilt of Southern Highbush Blueberry Caused by Ralstonia solanacearum” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/PP332).

BLUEBERRY BUD MITE

The blueberry bud mite is an eriophyid mite so tiny (i.e., 1/125 inch long) that it cannot be seen without magnification. Blueberry bud mite is an occasional pest in well-established blueberries in Florida. Bud mite injury is often confused with frost damage and may become more visible in late spring. In early spring, infested plants exhibit stunted, succulent, fleshy, closely packed, reddish, and rosetted buds, which may dry up and often fail to open. Bloom on infested plants is reduced. Affected berries are small and rough and may have small, reddish pimples or blisters on the fruit surface. Sanitation by aggressive, timely pruning of infested branches can be helpful. Mechanical topping (i.e., hedging old fruiting twigs) immediately after harvest greatly reduces bud mite incidence the following year. Bushes that may be infested with blueberry bud mite should never be used for propagation. The application of horticultural oil immediately after harvest can help in the control of blueberry bud mite. New miticides, Magister® (fenazaquin), Portal® (fenpyroximate), and Kanemite (Acequinocyl) were recently registered in blueberries and should provide some protection against eriophyids (blueberry bud mites belong to this group). The insecticide Apta® (tolfenpyrad) should also provide protection against eriophyids. Conventional insecticides such as pyrethroids have miticidal effects and can be used to help reduce bud mite infestation. See Table 2.

CHILLI THRIPS

Chilli thrips are the most significant pest problem in southern highbush blueberry in Florida. Adults feed on blueberry foliage in late spring through early fall, typically beginning shortly after the bushes are pruned. Chilli thrips feed primarily on young leaves, causing leaf bronzing and shoot dieback. During heavy infestation, the edges around younger leaves and stems are eaten and leaf curling and distortion occurs. Chilli thrips are smaller than flower thrips and are approximately 0.04 inches long with dark fringed wings and dark spots across the back of the abdomen. Insecticides that can be used to manage chilli thrips include Apta® (tolfenpyrad), Exirel® (cyantraniliprole) Assail® (acetamiprid), Sivanto® (flupyradifurone), Surround WP® (kaolin), and Malathion. See Table 2 and EDIS publication ENY-2053, “Chilli Thrips on Blueberries in Florida” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN1298).

DIAPREPES (CITRUS ROOT WEEVIL)

See previous discussion (in the Harvested Fruit section).

DIEBACK DISEASES OF SOUTHERN HIGHBUSH VARIETIES

Most southern highbush varieties are hedged immediately after harvest. Hedging cuts can serve as an entry point for many stem pathogens. At the end of each day of hedging, application of broad-spectrum fungicides, such as Captan mixed with Prophyt®, may help reduce infection. Resistance to azoxystrobin has been confirmed for Anthracnose stem dieback in central Florida. Do not use Abound® as a stand-alone application where resistance is known but tank-mix with Captan or Bravo. See Table 1 and EDIS publication PP347, “Botryosphaeria Stem Blight on Southern Highbush Blueberry in Florida” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/PP347).

FLATHEADED BORERS

See previous discussion (in the Harvested Fruit section).

FLEA BEETLES

The blueberry flea beetle in the genus Colaspis can cause serious damage to blueberry foliage during the summer months. Flea beetle eggs, and possibly adults, overwinter in the leaf litter of blueberry fields. Eggs are very small and orange yellow in color; hatching coincides with leaf bud opening. Larvae migrate to the foliage and feed on blossoms and leaf margins, giving the leaves a notched appearance. The larval stage takes 9–20 days to complete. Fully-grown larvae fall to the soil and pupate, with adults emerging approximately 15–28 days later. Adults are less than 0.25 inches in length, oval shaped, and a shiny copper bronze or metallic blue in color. They chew small holes in the foliage. Adults mate and lay up to 200 eggs per female. The blueberry flea beetle has several generations per year in the southern United States. See Table 2 and EDIS publication ENY-411, “Insect Management in Blueberries in the Eastern United States” (https://journals.flvc.org/edis/article/view/116379/114535).

IMPORTED FIRE ANTS

See previous discussion (in the Dormant Plants section).

SPIDER MITES

The southern red mite is the key spider mite pest attacking blueberry plants in Florida. Southern red mites primarily infest the lower side of the leaf, giving the leaf a bronzing appearance when the population is high. Southern red mites produce a protective web over the infested surface to protect them from predators. The underside of leaves should be closely examined with a 10x hand lens for adults, white shed skins, and webbing. Tapping foliage onto a sheet of white paper can also be used to find adult mites. A few miticides, including Magister® (fenazaquin), Portal® (fenpyroximate), and Kanemite® (acequinocyl), have been labelled for spider mites. See Table 2 and EDIS publication ENY-1006, “Mite Pests of Southern Highbush Blueberry in Florida” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN1284).

WHITE GRUBS (GRUBS OF ASIATIC GARDEN BEETLE, EUROPEAN AND MASKED CHAFER, AND ORIENTAL BEETLE)

White grubs are the larval form of certain beetle species, such as the masked chafer. They feed on blueberry roots, and damaged plants have the appearance of drought stress. It may take a number of years for larvae numbers to increase to a damaging level, although feeding injury on young plants can quickly result in symptoms and plant death. Masked chafer larvae are up to 1 inch long, with whitish bodies and brown head and legs. See Table 2.

YELLOW-NECKED CATERPILLAR

Yellow-necked caterpillars feed on the foliage of blueberry plants. Their bodies are covered with long, fine, whitish hairs. The head is black, and the area behind the head is yellow. Feeding by newly hatched caterpillars can skeletonize the foliage, leaving only the large leaf veins. In significant infestations, plant defoliation can occur. This can be minimized by pruning out infested stems. See Table 2.

Nonproblematic Diseases in Florida

Note: The diseases listed below have not been problematic for Florida growers to date.

MUMMY BERRY

Mummy berry is currently not an important disease of southern highbush blueberry in Florida. However, the disease is a major issue in production areas north of Florida. Florida growers concerned about potential mummy berry problems are encouraged to contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office for diagnostic confirmation and additional information (http://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/find-your-local-office/).

EXOBASIDIUM FRUIT AND LEAF SPOT

The fungal pathogen Exobasidium causes green to white spots on leaves and fruits that sporadically impact yield and fruit quality in Georgia and other parts of the Southeast. The disease has only been a problem in the northernmost production areas in Florida to date. Specific dormant applications have been shown in Georgia to help reduce Exobasidium but are not recommended for Florida production. Florida growers who suspect Exobasidium should contact their local UF/IFAS Extension office for confirmation and management options (http://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/find-your-local-office/).

VIRAL BLUEBERRY DISEASES

Diseases caused by viruses that include blueberry shoestring virus, blueberry scorch virus, and blueberry shock virus (among others) impact highbush blueberry production in northern states but are not known to occur in Florida production. Blueberry red ringspot virus and blueberry necrotic ring blotch virus occur in Florida but do not significantly impact production. Florida growers who suspect viral blueberry diseases should contact their local UF/IFAS Extension office for confirmation and management options (http://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/find-your-local-office/).

Commonly Recognized Stages of Flower Bud Development for Southern Highbush Blueberry

Credit: Jeff Williamson, UF/IFAS

Credit: Jeff Williamson, UF/IFAS

Credit: Mark Longstroth, Michigan State University Extension

Credit: Mark Longstroth, Michigan State University Extension

Credit: Mark Longstroth, Michigan State University Extension

Credit: Jeff Williamson, UF/IFAS

Credit: Jeff Williamson, UF/IFAS

Management Option Tables

All the following tables list registered pesticides that should be integrated with other pest management methods. Additional information on integrated pest management methods can be requested from UF/IFAS Extension horticulture or agriculture agents. A list of local UF/IFAS Extension offices is available at http://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/find-your-local-office/.

This publication was adapted for Florida from the 2024 Southeast Regional Blueberry Integrated Management Guide, developed by the Southern Region Small Fruit Consortium, available at https://secure.caes.uga.edu/extension/publications/files/pdf/AP%20123-4_2.PDF. Thus, major contributions were made by the original editors: Commodity Editor — Ash Sial (University of Georgia); Section Editors — Entomology: Aaron Cato (University of Arkansas), Ash Sial (University of Georgia), Doug Pfeiffer (Virginia Tech), and Jim Walgenbach (North Carolina State University); Horticulture: Eric Stafne (Mississippi State University), Jayesh Samtani (Virginia Tech), and Elina Coneva (Auburn University); Pathology: Bill Cline (North Carolina State University), Mary Helen Ferguson (Louisiana State University), Rebecca Melanson (Mississippi State University), Jonathan Oliver (University of Georgia), Raj Singh (Louisiana State University), and Nicole Gauthier (University of Kentucky); Weed Science: Mark Czarnota (University of Georgia) and Katie Jennings (North Carolina State University); Vertebrate Management: Michael T. Mengak (University of Georgia) and David Lockwood (University of Tennessee); Pesticide Stewardship and Safety: Ash Sial (University of Georgia); and Senior Editors — Phil Brannen (University of Georgia) and Bill Cline (North Carolina State University).

Recommendations are based on information from the manufacturers' labels and performance data from research and Extension field tests.

Because environmental conditions and grower application methods vary widely, suggested use does not imply that performance of the pesticide will always conform to the safety and pest control standards indicated by experimental data.

This publication is intended for use only as a guide. Specific rates and application methods are on the pesticide label, and these are subject to change at any time. Always refer to and read the pesticide label before making any application! The pesticide label supersedes any information contained in this guide, and it is the legal document referenced for application standards.

Pesticide Emergencies

Poisonings: 1-800-222-1222

The above number automatically connects you with a local Poison Control Center from anywhere in the United States.

Pesticide Spills or Other Emergencies: 1-800-424-9300 (24 hours) CHEMTREC

Be prepared—visit www.chemtrec.com now for a listing of the information you will be asked to provide in the event of a chemical spill emergency.

Spills on Public Roads: In many cases, you can call CHEMTREC at 1-800-424-9300, call 911, or call the Florida Hazardous Material Planning Section at 1-800-320-0519 (cell: call *FDCA).

Environmental Emergencies (Contamination of Waterways, Fish Kills, Bird Kills, etc.): Call Florida Department of Community Affairs Response Team at 1-800-320-0519.

Pesticide Safety and Label Interpretation Resources:

- “Federal Regulations Affecting Use of Pesticides” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pi168)

- EDIS Topic on Pesticide Labeling (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/topics/pesticide_labeling)

- “Toxicity of Pesticides” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pi008)

Sprayer Calibration: Sprayer calibration is very important. Sprayers should be calibrated often to keep from accidentally using excess pesticides because of nozzle wear, speed increases, and other calibration problems. Failing to calibrate often costs money, may cause crop damage, and is unsafe. Below is a list of online resources that deal with calibration of pesticide applicators.

- “Calibration of Herbicide Applicators” (https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-wg013-2020)

- “Pesticide Calibration Formulas Information” (https://ufdc.ufl.edu/IR00004194/00001)

Pollinator Protection

Before making pesticide applications, monitor insect populations and signs of plant disease to determine if treatment is needed. If pesticide (fungicide, insecticide, or miticide/acaricide) application is necessary, please do the following:

- Use selective pesticides to reduce risk to pollinators and other non-target beneficial insects. Look for pesticides with low toxicity to bees and with short residual activity when possible.

- Read and follow all pesticide label directions and precautions. The Label is the Law! The EPA now requires the addition of a “Protection of Pollinators” advisory box on certain pesticide labels. Look for the bee hazard icon in the “Directions for Use” and within crop specific sections for instructions to protect bees and other insect pollinators.

- Minimize in-field exposure of bees to pesticides by avoiding applications when bees are actively foraging in the crops. Apply pesticides in the early evening to allow for maximum residue degradation before bees return to forage the next morning. Bee foraging activity is also dependent upon temperature and density of flowers in the crop field. The greatest risk of bee exposure is during crop bloom. If applying outside of crop bloom, consider mowing flowering weeds in and around the field prior to pesticide application.

- Follow label directions to minimize off target movement of pesticides. Do not make pesticide applications when the wind is blowing towards beehives or off-site pollinator habitats.

For additional information relative to pesticide hazards to pollinators, see Georgia Pest Management Handbook (https://extension.uga.edu/programs-services/integrated-pest-management/publications/handbooks.html).

Table 1. Disease management options. Cells containing “?” indicate undetermined effectiveness.

Table 2. Insect and mite pest management options.

Table 3. Efficacy of selected fungicides against blueberry diseases. Ratings range from least to most (+ to +++++) effective. “NA” indicates there is no claimed efficacy. Cells containing “???” indicate fungicides are untested in Florida or too new to have efficacy ratings for that particular disease.

Table 4. Fungicide classes with moderate to high risk of resistance development (generally single sites of action).

Table 5. Fungicide classes with low risk of resistance development (generally multiple sites of action).

Table 6. Seasonal "at a glance" fungicidal spray schedule options for blueberry.

Weed Management Options

Table 7. Preemergence chemical weed control for blueberry.

Table 8. Postemergence chemical weed control in blueberry.

Table 9. Weed response to herbicides used in small fruits. Responses are indicated by the following: E = Excellent, G = Good, F = Fair, P = Poor, N = No activity, – = No data available.

Table 10. Efficacy of preemergence and postemergence herbicides for annual and perennial grass and sedge weed control. Responses are indicated by the following: E = Excellent, G = Good, F = Fair, P = Poor, N = No activity, – = No data available.

Plant Growth Regulators

Table 11. Plant growth regulator use in Florida blueberry production. “NA” indicates that this item is not applicable.