Introduction

Many Extension professionals are working to encourage behavior change in the community. In the case of Horticulture and Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ educators, these behaviors may include 1) Reducing excess landscape irrigation; 2) Leaving grass clippings on the lawn instead of blowing them onto streets and into storm drains; and 3) Selecting the right plant for the right place. When Extension professionals encourage behavioral changes in their community through educational programming, they may be using some elements of social marketing, although it is not often called that. Social marketing recognizes that providing education alone does not necessarily result in a change in behavior; this approach applies elements of traditional marketing to behavior changes that benefit the community's health and wellness, the environment, or financial well-being. There are several commonly used strategies used by social marketers to encourage new behaviors or behavior change: prompts and reminders, incentives, and changing social norms. The purpose of this article is to describe one strategy used in social marketing, commitment, and make recommendations for its use in Extension programming. While the examples within are horticulture-specific, the document and the resources within areiintended for Extension professionals working both within or outside of this field.

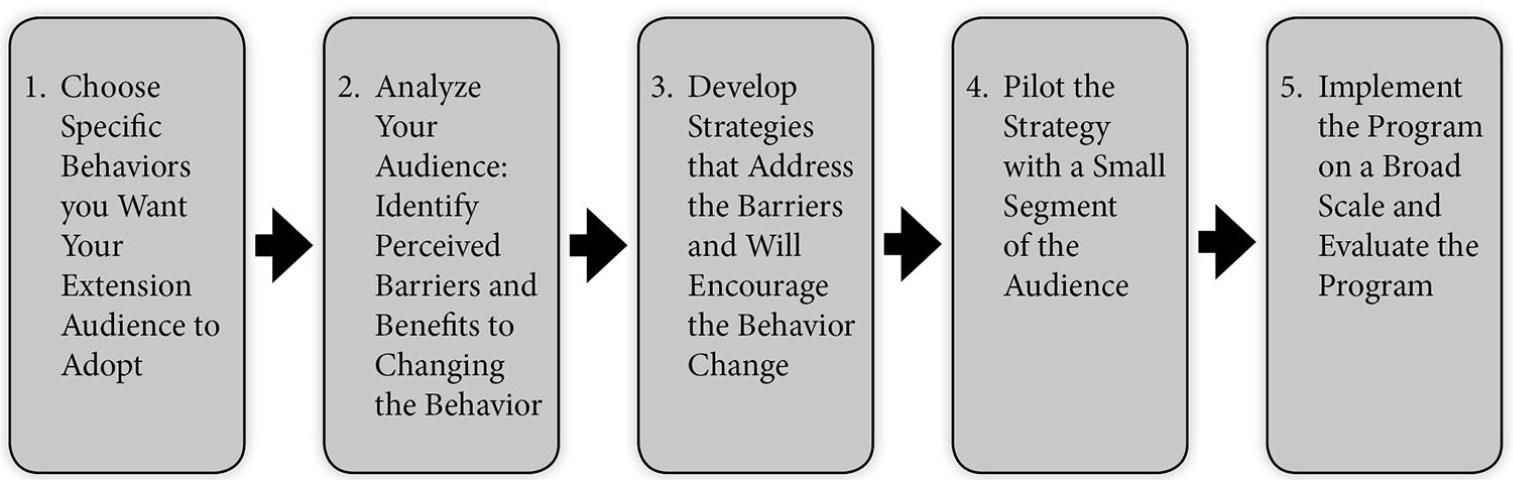

Social marketing has been used successfully in seatbelt safety, recycling, and hand washing campaigns, to name a few examples. The social marketing process (Figure 1) involves first selecting what behavior change is desired and analyzing how the audience feels about that behavior. Extension educators can use an understanding of their clients' reservations and inclinations toward a behavior (barriers and benefits) to develop strategies to encourage behavior change. The strategies may be piloted on a small scale, modified if necessary, and then implemented on a large scale and further evaluated.

Credit: Adapted from McKenzie-Mohr (2011)

Commitment as a Strategy to Encourage Behavior Change

A commitment is a positive intention to take some action, such as a pledge or a promise, usually made publicly. Examples of commitments include signatures on a pledge card, buttons and bumper stickers that indicate behavior change, or yard signs that tell the neighbors what a homeowner has done. For example, fans of the musician Jack Johnson make public pledges to reduce the use of single use plastic by posting their promise along with their photo on his social change webpage, All At Once (http://allatonce.org). Research has shown that commitments can increase the percentage of people who will adopt a new behavior and give up an old one (Kotler & Lee, 2008).

Further, if a small commitment is requested, participants will be more likely to adopt something bigger. Let's say some Extension educators are teaching about irrigation technologies and water conservation during a rain barrel workshop. If they ask their clients to commit to doing something small, (Will you check your irrigation system this weekend to make sure there are no leaks?) they are more likely to subsequently agree to something bigger. (Will you sign a pledge to install a rain shutoff device in the next 30 days?) Commitments may be verbal or written, and they may be made by individuals or groups. Written commitments are typically more effective than verbal ones, and group commitments are more effective than individual ones (McKenzie-Mohr, 2011; Rogers, 2003). Publicizing the group's commitment, such as through Internet or print media, increases effectiveness even more (Lehman & Geller, 2004; McKenzie-Mohr, 2011).

So how does this work? When people say they will do something, their perception of themselves changes. They feel responsible for the commitment and are inclined to follow through with the behavior change in order to maintain consistency with the new self-perception (Cialdini et al., 1978; McKenzie-Mohr et al., 2012). Participants in an Extension rain barrel workshop who said they would inspect their irrigation systems might begin to see themselves as people who use water wisely. Their perception of themselves as conservationists is strengthened with each new action. That makes them more likely to agree to an action that leads to an even bigger water savings. Further, some researchers believe that people desire to be seen as consistent; promising publicly to do something reinforces an outward sense of consistency and makes it easier to adopt the behavior (McKenzie-Mohr et al., 2012). Because we want people to think positively of us, we are inclined to do what we say we will do. When we ask people to do something, we use the commitment strategy to capitalize on this inclination.

Examples of Commitment

The following studies are just a few examples of the effectiveness of this strategy.

- A "food rescue program" targeted at restaurants and hotels in Portland, Oregon ("Fork it Over!") collected an estimated 9000 tons of food in six years. Part of the campaign asked food businesses to make written, public commitments to donate food. These commitments were publicized using posters in windows and social media, and included signed letters to other businesses encouraging participation (McKenzie-Mohr et al., 2012).

- A study conducted in 1995 demonstrated that individuals in a particular community who made a public commitment to recycle paper by having their names published in a newspaper recycled 40% more paper (Lehman & Geller, 2004).

- In 1992, US-based AT&T locations sought to encourage staff to work remotely to reduce pollution. The campaign included a commitment strategy and resulted in 56% of the staff working remotely at least monthly and an impressive 5.1 million gallons of gas saved (Kotler & Lee, 2008).

- A social marketing campaign in Toronto used a combination of signs, personal contact, and visual commitments to reduce car idling among motorists in waiting areas such as school parking lots and train stations (McKenzie-Mohr et al., 2012). Trained students contacted motorists in these parking areas, explained the issue, and asked the drivers to pledge to change their behavior and turn their car off when they arrived at the waiting areas. Each driver that made a commitment received a bumper sticker to let everyone else know about it and the campaign resulted in an idling reduction of 32%.

Table 1 presents a few suggestions for applying commitment to Extension programming to encourage sustainable landscaping behaviors.

Adopt Commitment as a Strategy

Commitment is easy to incorporate into existing Extension programs and can increase the occurrence of behavior changes. Consider asking for verbal or group commitments from clients throughout the course of Extension programs. Publicize the commitment when possible. Publicity increases the likelihood of behavior change and may foster a sense of pride and community in doing this behavior. Commitment is most effective when participants have positive feelings towards a behavior and when they make a free choice to commit. Evaluation is key in determining the extent of behavior change. The following is a summary of recommended best management practices for using this strategy.

Best practices for using commitment to encourage behavior change1

- Choose behaviors that are positively perceived by participants;

- Involve clients in identifying behaviors and crafting commitments;

- Use group, public, and written commitment when possible (as opposed to individual, private, and verbal), and make effective use of social media;

- Use existing methods of client communications to ask for commitment (newsletters, email lists, upcoming seminars);

- Use existing points of contact with target audiences such as garden centers, homeowner association meetings, and youth soccer games to ask for commitment;

- Evaluate to determine the impact and extent of behavior change and how commitments impacted the results.

1 Adapted from McKenzie-Mohr (2011).

Conclusion

Extension professionals can use their programs to increase behavior change among their clients by borrowing different tools from the field of social marketing. An easy and effective tool is to incorporate commitments into programming so that clients can publicly state that they endorse the behavior change and pledge to adopt it. It is a proven technique for increasing the percentage of the public that adopt new behaviors. Identifying target audiences and reducing barriers to adoption are ways agents can make behavior change easy, fun, and socially desirable. Extension professionals wishing to incorporate commitments and other social marketing tools into their existing programming can learn more from the following:

Resources

Fostering Sustainable Behavior: Community-Based Social Marketing (www.cbsm.com).

Making Your Community Green: Community Based Social Marketing for EcoFriendly Communities (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/uw263).

On Social Marketing and Social Change News and Views On Social Marketing and Social Change: (socialmarketing.blogs.com/).

Social Marketing in the Wildland-Urban Interface (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fr254).

Tools of Change: Proven Methods for Promoting Health, Safety, and Environmental Citizenship (www.toolsofchange.com/en/home/).

Water Words that Work (waterwordsthatwork.com/).

References and Further Reading

Cialdini, R., Cacioppo, J., Bassett, R., & Miller, J. (1978). Low-ball procedure for producing compliance: Commitment then cost. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 36(5), 463–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.36.5.463

Kotler, P., & Lee, N. R. (2008). Social Marketing (3rd ed.). California: Sage Publications.

Lehman, P. K., & Geller, E. S. (2004). Behavior analysis and environmental protection: Accomplishments and potential for more. Behavior and Social Issues, 13(1), 13–32. https://doi.org/10.5210/bsi.v13i1.33

McKenzie-Mohr, D. (2011). Fostering sustainable behavior (3rd ed.). Canada: New Society Publishers.

McKenzie-Mohr, D., Lee, N. R., Schultz, P.W., & Kotler, P. (2012). Social Marketing to Protect the Environment: What Works. Los Angeles: Sage Publishing.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York: Free Press.